The Austerity Diet

Looking back on how Israelis dealt with food rationing in the first years after independence—and who bore the burden of feeding their families

Oded Zwickel

Oded Zwickel

Oded Zwickel

Oded Zwickel

Israel’s national founder and first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, is remembered for many things: for his famous Declaration of Independence speech, for leading the country during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and for standing on his head, among other things. He is also remembered for a distinct time in the country’s history: the period of austerity, which was introduced as a means of dealing with the mass immigration to the young country. Officially it lasted from 1949 to 1959, but in reality, it ended much sooner.

The brand-new state opened the immigration gates that were blocked during the British Mandate, and masses of Jewish immigrants started arriving: Holocaust survivors and European refugees as well as Jews from Arab countries. Many of these immigrants came penniless, and the country needed to sustain them and support them. Financial need, backed by a socialist and anti-materialistic worldview, brought in Israel’s austerity regime.

In terms of food, austerity meant modest rations of food per person, according to very specific allowances, that differed from adults to children and babies and pregnant women. To ensure that every person received the allowance they were entitled to, coupons were used, and this was strictly supervised by the government. Most restrictions were lifted by 1953, when Israel started to receive compensation from West Germany for confiscation of Jewish property during the Holocaust. In the following years, the list of rationed goods became increasingly smaller, until it was entirely abolished. (Some food products were still not available in Israel until the late 1980s because of the Arab League boycott, but that’s a different story.)

During austerity, cooking was done on wicks or Primus stoves, and kitchenware was made out of tin or enamel. In the beginning, there were no electric refrigerators—only the kind you put ice blocks into. To save space in the icebox, cooler cabinets with mesh walls were used to store sensitive items like eggs and bread.

The difficult task of keeping a family fed, healthy, and happy under this regime was the daily struggle of the Israeli housewife. She had to stand in line at the grocery store, sometimes for hours. She had to struggle to obtain quality goods. And she had to improvise in the kitchen to be able to feed her family with the insufficient products she had. There was no variety, most products were scarce or nonexistent, and the quality of food was usually poor. To make due, substitutes were used. Women used egg powder instead of eggs and diluted margarine instead of butter. The idea was to create the dishes that the family had been accustomed to before, and naturally craved, using whatever was available. The substitutes were supposed to taste similar to the original products and provide the same nutrients.

Ashkenazi Jews, for instance, craved chopped liver, and thus an eggplant salad that looks and feels like chopped liver (even if it doesn’t really taste like it) was invented. There aren’t many austerity recipes that are still prevalent today, but this one is. There is even a commercial version of this mock chopped liver that can, to this day, be bought at the supermarket; it’s much cheaper than real chopped liver, has less cholesterol, and is a great solution for vegetarians.

Jews from Arab countries, on the other hand, craved rice, but instead they got a type of toasted pasta called ptitim, similar to Italian orzo or Sardinian fregola. Ptitim are, in fact, made of crumbled dough that is baked (at the factory) before it is boiled (at home). According to Wikipedia, “Ptitim was created in 1953, during the austerity period in Israel. David Ben-Gurion asked Eugen Proper, one of the founders of the Osem food company, to devise a wheat-based substitute for rice. The company took up the challenge and developed ptitim, which is made of hard wheat flour and toasted in an oven. Ptitim was initially produced with a rice-shape, but after its success, Osem also began to produce a ball-shaped variety inspired by couscous.”

This is why the product was colloquially known as “Ben-Gurion rice” and later as “Israeli couscous” in English-speaking countries. Even though they were born out of need, ptitim became a sort of comfort food that Israelis associate with their childhood, and a nostalgic staple of old-time Israeli cuisine.

Making something from nothing was the motto, and cookbooks and newspaper columns employed experts to help the young housewife feed her family with the meager allowance at hand. There were also free courses organized by volunteer organizations such as the Women’s International Zionist Organization.

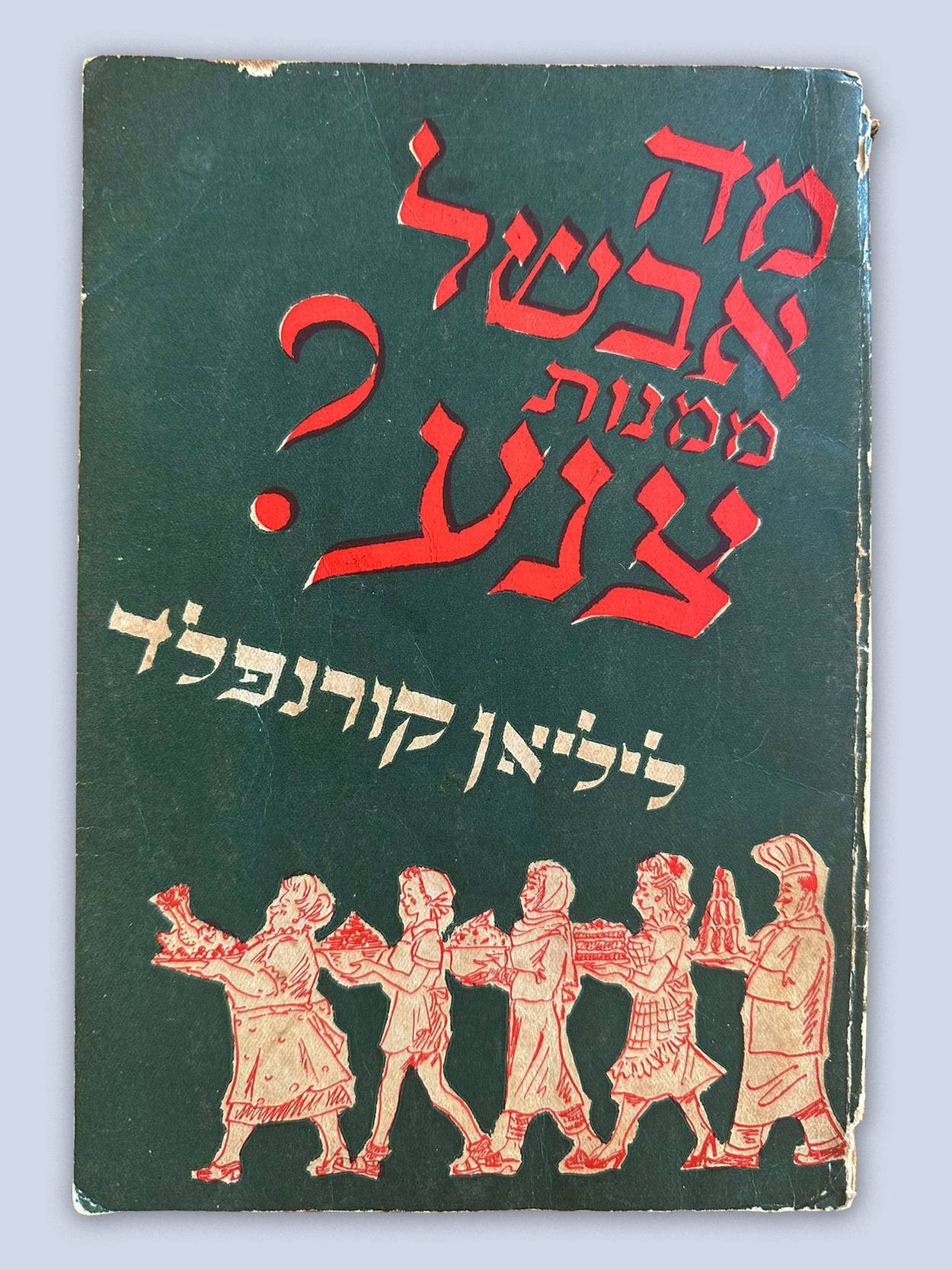

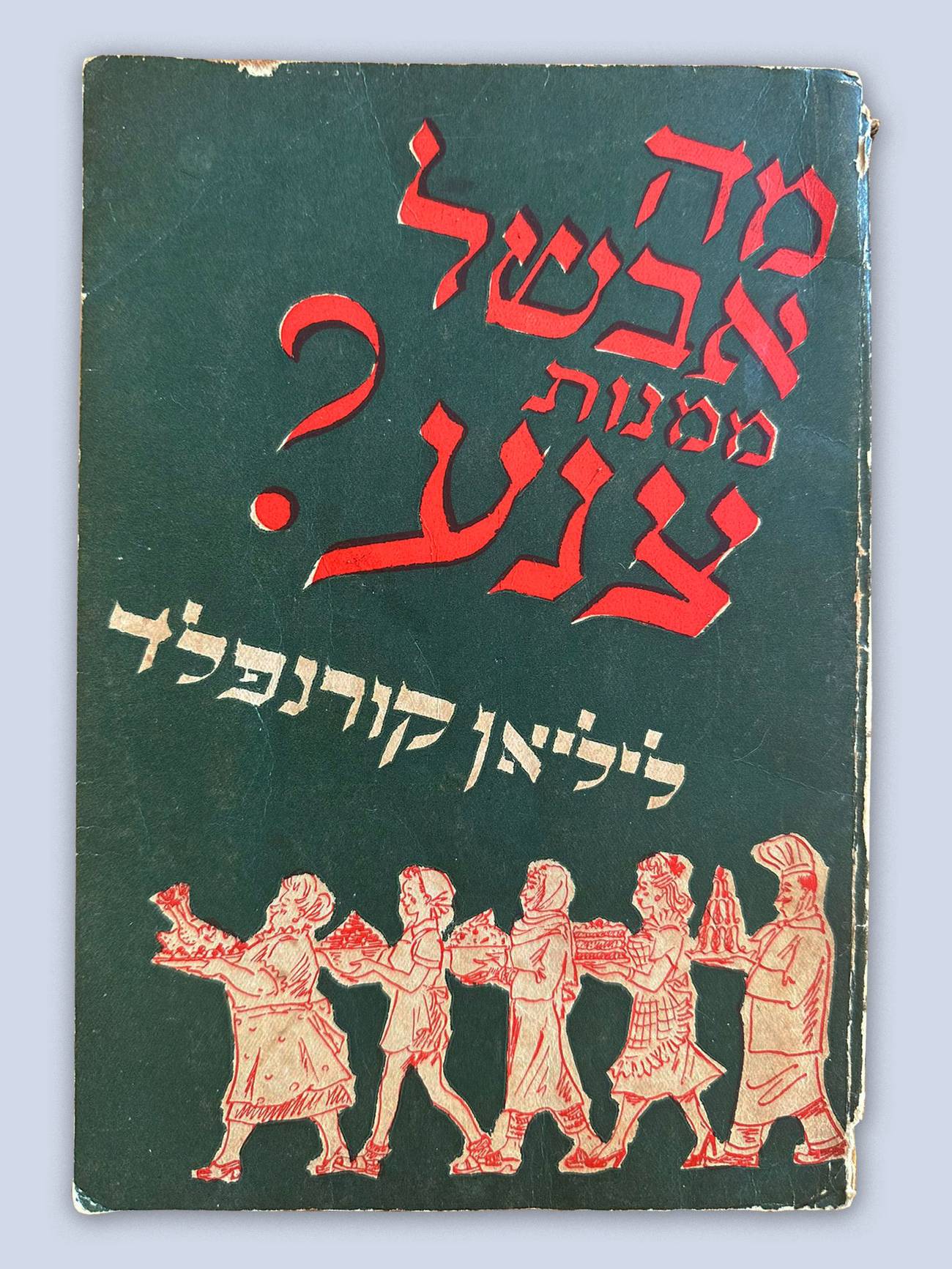

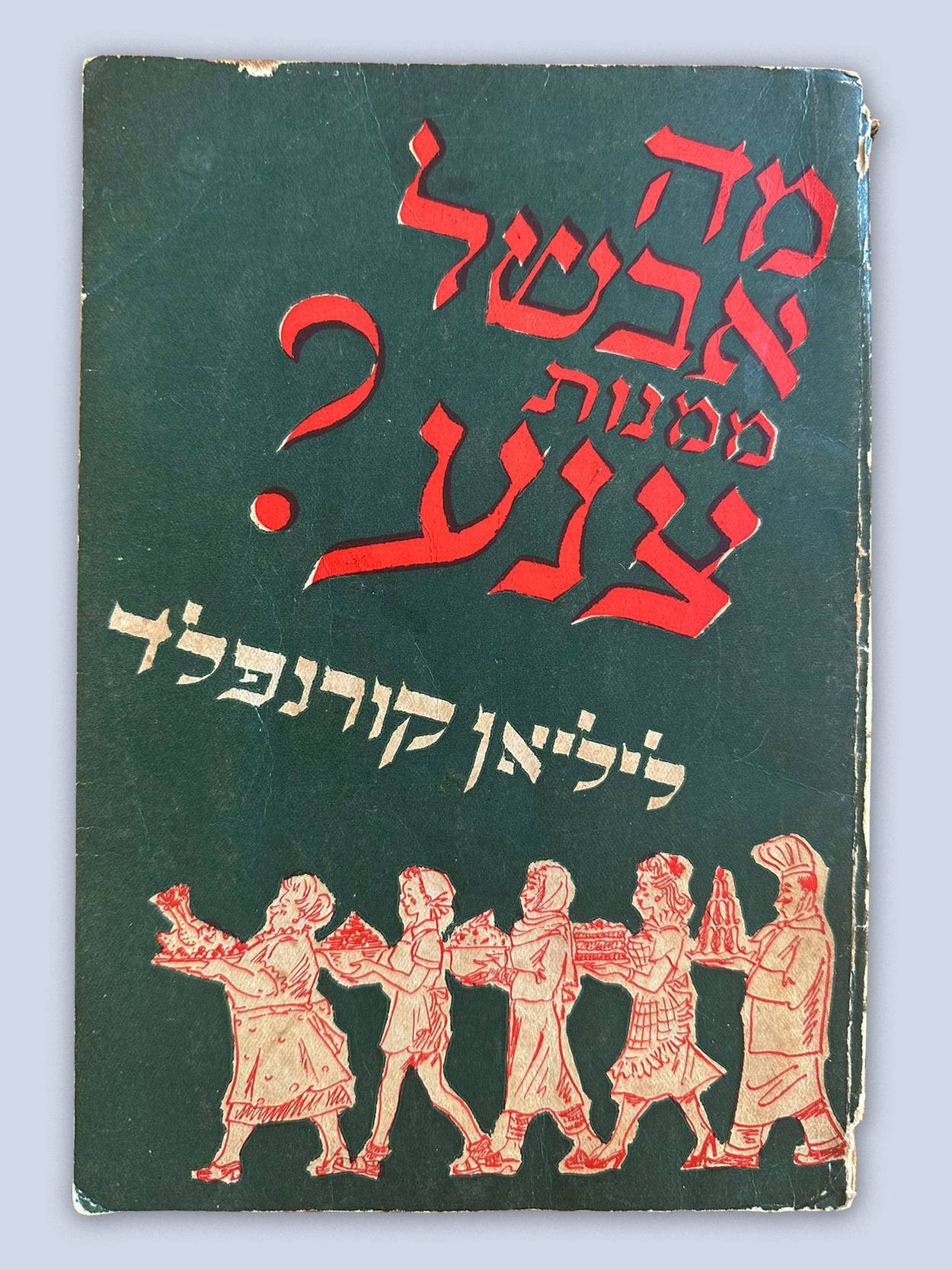

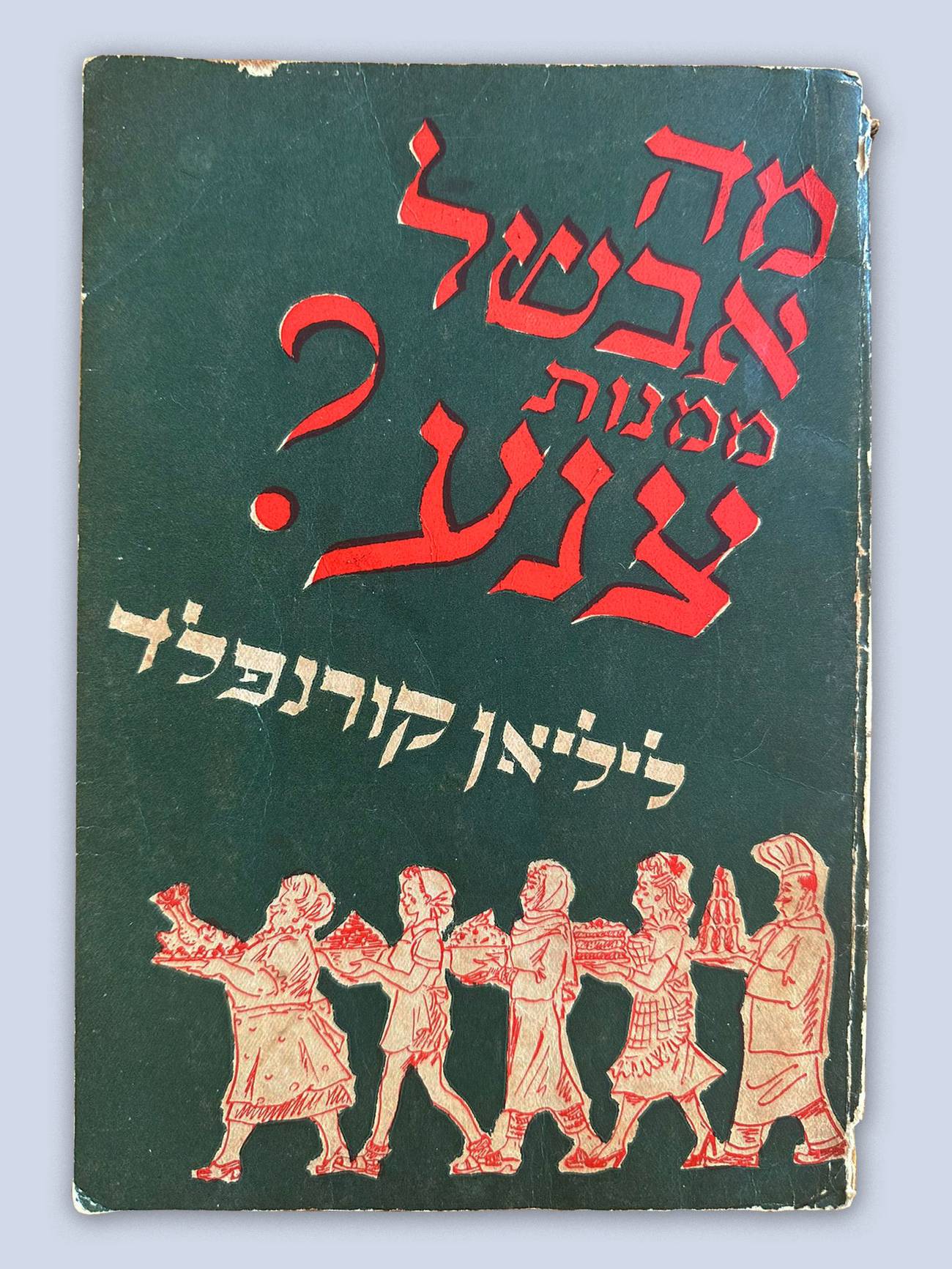

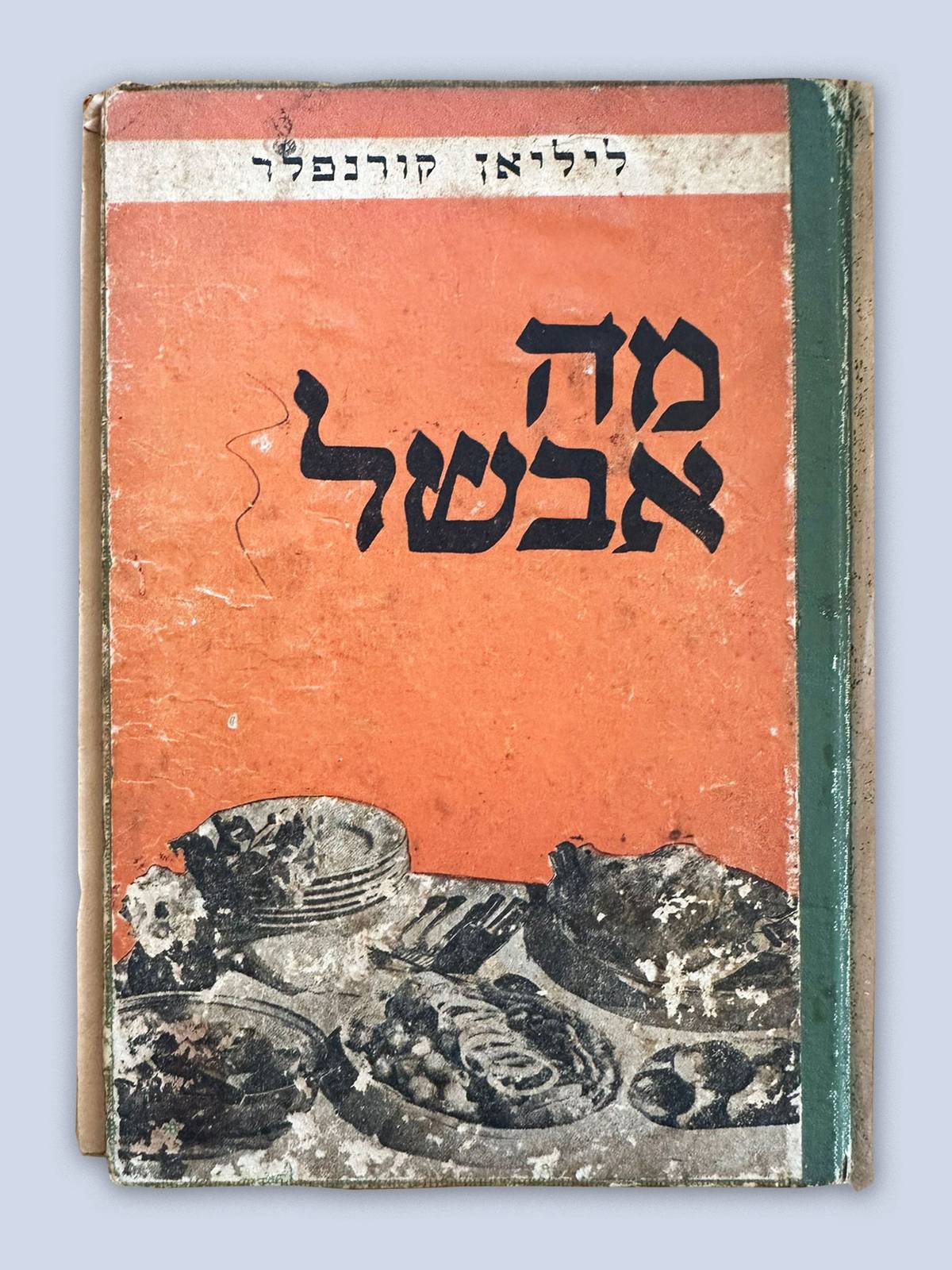

Lilian Cornfeld, who was born in Montreal in 1902 and made aliyah in 1922, was the burgeoning nation’s Martha Stewart. As a nutritionist and nutrition instructor, she became a pioneer in cookbook writing, publishing cookbooks in Israel from the early 1940s—before the State of Israel was established—to the late 1960s.

In 1949, Cornfeld published Ma avashel me-manot tsena? (“What Shall I Cook from Austerity Rations?”)—which was kindly lent to me by Oded Zwickel, owner of Ha-Tsrif, a privately owned mini-museum dedicated to vintage Israeli kitchens and their contents. Thus, I had the pleasure of browsing through this and various other cookbooks of the time, all of which have since become precious collectors’ items.

The book has a foreword by the first Israeli government’s minister of rationing and supply, Dov Yosef—the man who was in charge of determining the citizens’ necessities in order to ration their quantity and ensure their supply. In his prologue, he attempted to explain the rationale behind the rationing and to put the reader’s faith in Cornfeld, ensuring her that this manual will enable her to feed her family.

Cornfeld also addressed her readers personally: “For the housewife in Israel: The recipes in this book are based on the same food ingredients. The austerity regime requires a new approach by the Israeli housewife to planning the menus and cooking them ... The state’s slogan is to ensure a maximum of food for a minimum of expenses and to provide everyone with equal and appropriate portions as much as possible. In fact, every housewife is an important factor in our economy. Her strength and talent in managing the house were mobilized to revive our economy.”

In 1953, a new edition was published under the name What Shall I Cook?—still in full-on austerity mode: “As long as butter or cream have not become everyday commodities, we will use margarine instead of butter, leben (a dairy product made of fermented milk) and milk skin instead of cream. We will make fake whipped cream and we will skillfully use milk powder and egg powder if they are available.” Naturally, the book opens with a long list of substitutes, such as using milk powder mixed with gelatin instead of whipped cream; yeast dough dumplings instead of potatoes; a mixture of leben and oil instead of mayonnaise; and many more. It is explained that two flat tablespoons of egg powder mixed with 2.5 spoons of warm water equals one egg.

Powders were all the rage, and the government’s PR machine tried to convince the public that they were not just as good as the real thing, but better. Dr. Erela Taharlev Ben Shachar—a historian of science who focuses on nutrition and the author of forthcoming book From Counting Values to Counting Calories: The History of Nutrition in Israel—researched this point extensively.

Oded Zwickel

“The government’s propaganda for powders among women emphasized very much the ‘modern’ aspects of them,” she told me. “The fact that they are compact, that you don’t need to frequently go to the grocery store, that they demonstrate rational thinking. The message was that anyone who adopts scientific thinking should understand that there is no difference between an egg and egg powder. Those who refused to see the powder as the ‘real thing’ were called ‘primitive.’”

I asked Ben Shachar if austerity caused any health problems or deficiencies. “At the beginning of the austerity period there was a discussion about calcium and riboflavin deficiency,” she replied. “Later it was widely believed that the powders solved this problem. Later on, in 1951, there was concern that the children were not getting enough calories. It was probably not justified, but at the time some experts demanded an increase of sugar in the children’s allowance in order to increase the number of calories they receive.”

Ben Shachar believes the austerity regime perpetuated and deepened inequality between men and women. “Men were behind the rationing, and the belief was that as long as the menu contained a sufficient amount of proteins, carbohydrates, and calories, it is satisfactory, even if it condemned the women to hard work, as well as a great emotional investment. Such bland and monotonous food could not be distributed to the population if the women weren’t willing to spend extra hours turning these inedible ingredients into palatable or at least edible food.

The austerity regime perpetuated and deepened inequality between men and women

“Although austerity was seen as an eating regime that embodies egalitarian ideas and socialist concepts, in practice, there were populations that received more and populations that carried more of the burden,” she told me. “According to my research, as well as that of historian Orit Rozin, austerity discriminated against women. The way in which women were discriminated against was not reflected in the amount of food they received but in the amount of work that was required of them and in the ‘transparency’ of their work, which was not taken into account as a type of resource. And there was also a more direct aspect. According to Rozin, women often saved food from their mouths and gave their portions of protein or sugar to the children. This is a phenomenon that was known all over the world. After all, austerity was not an Israeli invention—the Israelis ‘copied’ it from Britain, and the U.S. also had its own food regime during WWII.”

Women weren’t required to merely be great cooks and housewives; they were expected to be magicians, as is evident by this magic trick Cornfeld mentioned: how to make two chickens from one. “Some know how to serve two chickens from one chicken,” she wrote. “They strip the skin with the wings and part of the legs, fill it with desired stuffing, and here is a second chicken. It is not easy to learn to remove the skin in its entirety, but it will not be difficult to remove the skin from the neck as well as from the legs. Fill this skin with flour seasoned with salt, pepper, onion, and parsley, or with bread stuffing. Sew and roast together with the chicken, or cook in soup.”

One wonders if Israelis celebrate their Independence Day with barbecues and copious amounts of meat as a way to remind themselves that at the beginning of this journey, meat was hard to come by.

The quality of products deteriorated rapidly. By the end of 1950, grocery stores attempted to sell products that were unfit for human consumption, and women started to protest against this. The press printed women’s complaints about shortages and the difficulty to obtain even the rationed goods.

One of the great spokespeople of the time was journalist Ora Shem-Or—mother of lyricist Mirit Shem-Or and mother-in-law of deceased Israeli pop star Svika Pick (she sadly didn’t live long enough to witness her granddaughter, Daniella Pick, marry Quentin Tarantino).

Ben Shachar remembers Ora Shem-Or and her regular column in women’s magazine La’Isha fondly: “She was a great publicist and a woman with liberal views while everyone else was Mapai,” the democratic socialist political party, which was dominant at the time. “Her writing was critical and from the point of view of women. She wrote from experience, from familiarity with long hours of standing in line, with the need to provide a holiday dinner in the absence of materials, with the terrible anxiety for babies that might not be getting sufficient nutrition, and with the huge gap between the women who had to feed their families, and the men—the scientists and government officials who dictated what to eat and had no idea what this required of the person who really cooks. She gave a voice to the rage and frustration of women in the newspaper and even motivated them to political and consumer activism.

“There was also a great satirical column in La’Isha, written by Yosef Vinitski, although the identity of the writer was top secret at the time,” Ben Shachar continued. “It was written as a diary of a baby who documented what its parents were saying. In one column, the baby described how ‘they wrote in the newspaper that there was milk, so Mommy ran to the grocery store, and the shopkeeper said there was no more. Mom said, ‘But it was written in the newspaper,’ so the shopkeeper answered, ‘then boil the newspaper.’ Beyond the fact that this was a terribly funny column, it expressed the criticism of the government, the irony of the government’s control over food, and the anxiety of women to feed their babies.”

All of this, of course, brought on corruption and the emergence of an active black market. In the early years, idealism and hope helped the frustrated public through this hardship. For a while it was perceived as a collective effort. But after a few years, people were fed up, and buying on the black market became more common for whoever could afford it. “In one of columns of the satirical baby diary in La’Isha,” Ben Shachar recalled, the baby supposedly said, “‘If you boycott the black market, you should boycott me—because I am entirely a product of the black market.”

Buying food products illegally on the black market was especially prevalent in the city. People living in the country, on a kibbutz or a moshav, had it easier when it came to food since they could grow their own. But even this was not always the case. “A new study by historian Gadi Algazi shows that the Arab population was discriminated against,” Ben Shachar told me. “It was in the Arab villages that the inequality and lack was felt more than in the city. It is commonly thought that villagers suffered less than city dwellers because they had direct access to fruit and vegetables, but this was only true among the Jewish population. Since the rations in the city were given per person, it was difficult to discriminate against the Arabs there. But the method of division in small settlements was ‘collective,’ so that each village and settlement received the food for all its inhabitants, and Arab villages received less than Jewish ones.

“Generally speaking, the most sought-after product on the black market was ‘undiluted food’ and food that wasn’t ‘fake.’ The quality of the food that reached consumers in the days of austerity was very poor. According to historian Orit Rozin, there was sand in instant coffee and sawdust in candy. There was a story about a shopkeeper who, when she received undiluted cheese (not mixed with milk powder), she refused to sell it to customers and kept it all for her family. So, popular items on the black market were undiluted milk, undiluted wine, and clean coffee.”

But not everyone remembers the period of austerity as a bad one. My mother, Livia Novi Kessler—a Holocaust survivor born in Transylvania—made aliyah with her parents in 1950. She was 12 years old at the time and, as a young girl, remembers this as an exciting time. “For the first year and a half we lived in a Ma’abara (an immigrant and refugee absorption camp) in Acre,” she told me. “We cooked on a Primus and bought supplies with food coupons and stood in line to get them, but I don’t ever remember being hungry. First of all, my family went through the Holocaust and then lived in Communist Romania, so the austerity in Israel was much better than any of those things. And even during austerity we had foods in Israel that we never had in Romania, like oranges, lemons, and even chocolate. I remember it was weird to me that we didn’t have apples, but the oranges more than made up for that. We were thankful for whatever we got because before that, we had much less. Plus, we were Zionists, and we felt that this food shortage was for a great cause. Instead of good food and luxury, we had idealism. Living the Zionist dream was much more important to us than food or any kind of material goods. We really didn’t mind the hardship.”

Dana Kessler has written for Maariv, Haaretz, Yediot Aharonot, and other Israeli publications. She is based in Tel Aviv.