The Perfect Quince Jam

Trying to recreate a recipe that carries a history as broad as the Mediterranean, and as specific as my grandmother’s kitchen

I can remember every time I’ve been disappointed by a jar of quince jam. There was the dusty, gourd-shaped jar I bought at a Jordanian grocery store in Chicago, the Wilkin & Sons Quince Jelly I knew already would fall flat even before agreeing to pay a double-digit figure in freight from the U.K., the half-sized jar I bought at Le Bon Marché in Paris and managed to slip past customs, the North African one algorithmically pushed to me on Amazon. In the near decade since my grandmother’s death, I have tried again and again to find a quince jam similar to the one she used to make, but none has ever come close.

My grandmother was born in Alexandria, Egypt, in 1924. As a Jew living in the cosmopolitan port city with thousands of years of international influence, the food she ate at home and on the streets, and later cooked, even when living in her apartment on 98th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, had no single point of origin. Nothing was ever only one thing; it was always an archeological dig site of Egyptian, French, Greek, Turkish, Spanish, Italian, and Jewish influence.

The beating heart of this vast Mediterranean influence is the quince.

Although rarely eaten in the United States, the quince, similar in appearance to a golden apple or a pear, is a staple of Mediterranean culture and has perhaps the most illustrious history of any single fruit. In the myth of Paris of Troy, the young prince presents Aphrodite with a quince—a gift that would accidentally set off the Trojan War. In the 11th of his 12 labors, Hercules is tasked with stealing a quince from Hera’s garden. In Cato the Elder’s work De agri cultura, the oldest complete work of Latin prose, Cato describes techniques for preserving quinces. Apicius, the ancient Roman gourmet, was known to have prepared a dish of quince, honey, and leeks. The Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne decreed that quince trees should be planted in his gardens. It is even believed by some that the apple eaten by Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden was not an apple at all, but was, in fact, a quince.

The quince also shows up throughout Jewish history. After Spanish Jews were expelled in the 1400s, they brought membrillo—a dark, fragrant quince paste, more like candy than jam—to their new homes across the Mediterranean in countries like Egypt, helping further spread the fruit’s popularity. Membrillo, still prepared the way it was hundreds of years ago, is sometimes served at Sephardic new year celebrations, and can be found in the U.S.

Off the tree, quinces have a pale white flesh and a hard, bitter taste—imagine the worst pear you’ve ever eaten. But when cooked down they sweat out a tangy sweetness that has helped their influence last, literally, for thousands of years.

When my grandmother came to the United States after the expulsion of Egyptian Jews, she always found ways of filling her kitchen with the most elusive ingredients from her past life. One was more likely to find quinces and filo dough pastries in her fridge than white bread.

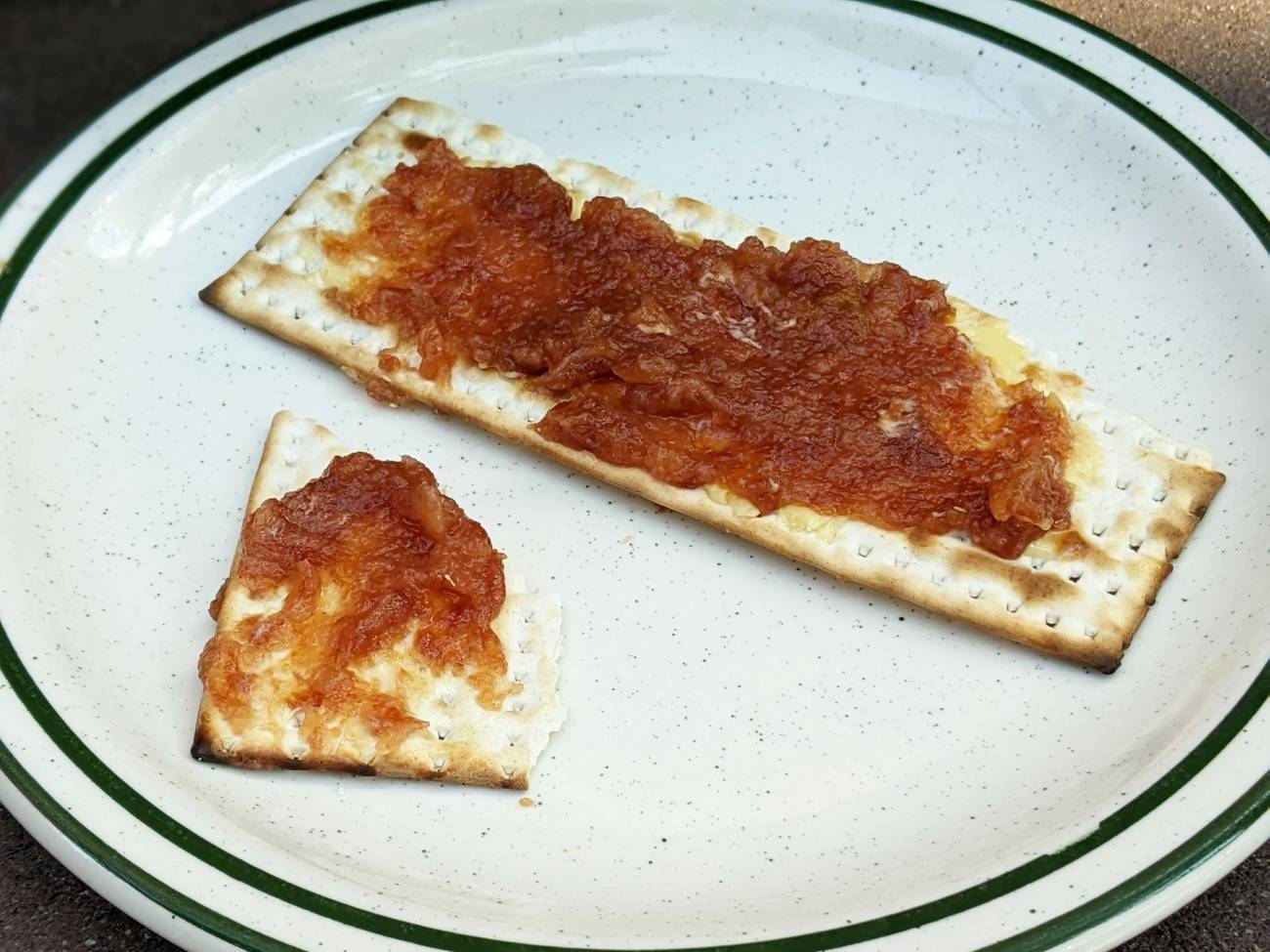

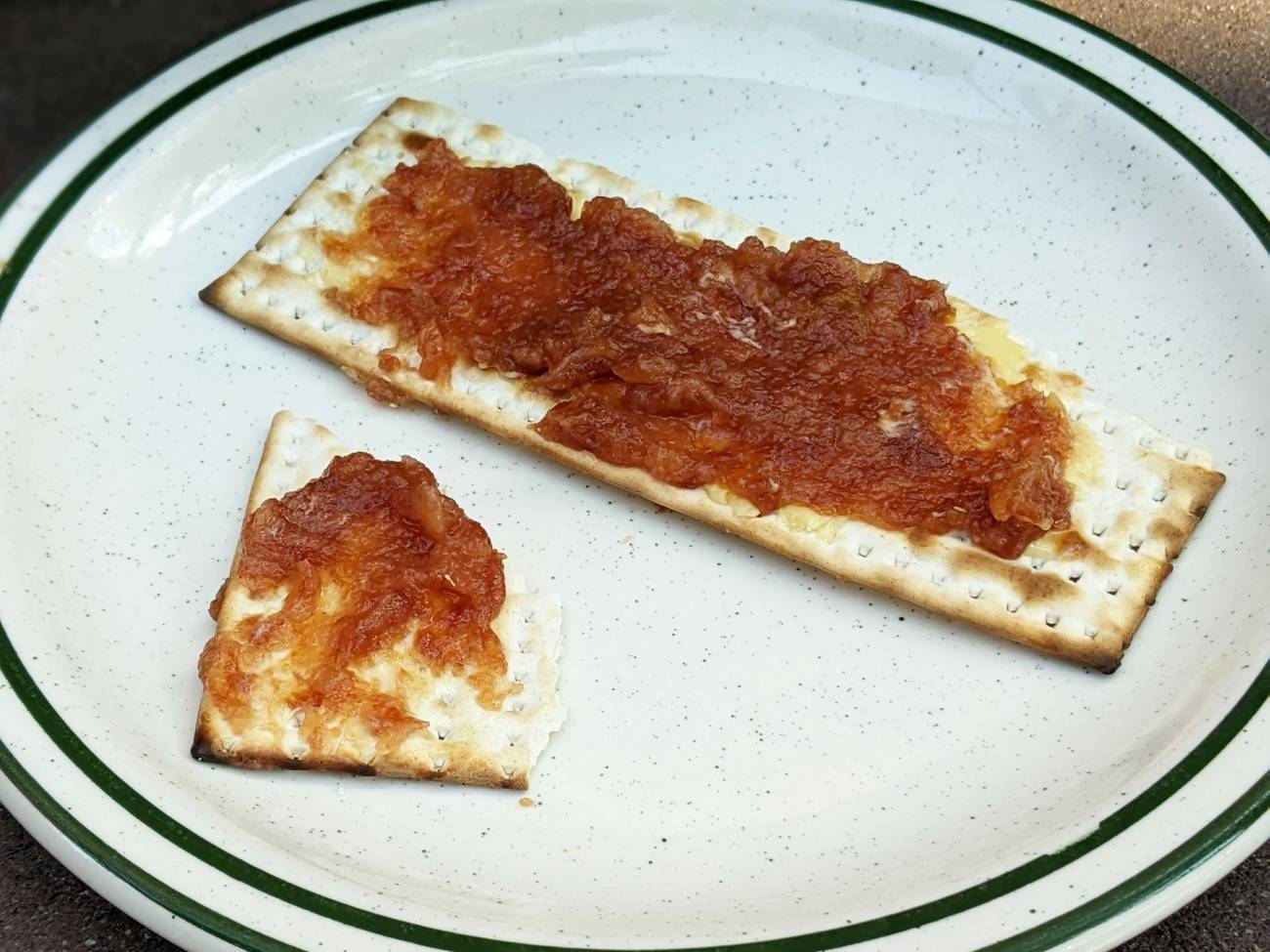

As a child, I thought her cooking was so good that she ought to open her own restaurant. Maybe it was this flattery that won me jars of her quince jam for special occasions. Whenever I came home from college, there was always a jar in her fridge and a warning to others not to touch it. In the first week of September, as my birthday approached, I always knew, even when she was in her late 80s—even when I told her not to go through the trouble but hoped she might not listen—that it would always be there waiting for me. I would eat it sitting on her kitchen counter, often straight from the jar with a spoon, or as she prepared it, in a kind of accidental millefeuille of our family history: slathered on a decadent cloud of French butter atop a cracked shard of matzo, which she kept in the house year-round.

There is, of course, no way of recreating the experience of walking into her apartment on the first cold afternoon of early fall and finding a jar of quince jam prepared just for me. But, as it turns out, there also isn’t even a way to find a facsimile of it. When I am even able to find it in the U.S., commercially available quince jams are often too treacly. Sometimes they are just a pale jelly without any fruit at all, which for me is more like drinking the melted ice water at the bottom of an iced coffee rather than the real thing. Worst of all, the color is always wrong. Most quince jams are either electric orange or a deep burgundy, while my grandmother’s was a shade of pink-rose salmon, verging on orange, like the faded orange seats on the MTA. The way quince was my grandmother’s totem to life on the Mediterranean, for me it was my totem to her. At times since her passing, desperate to taste that elusive but familiar fruit, I have resigned myself to buying a block of membrillo, but it has never once taken me back to those afternoons in her kitchen.

This year, as the first week of September approached, I decided to try and recreate my grandmother’s quince jam myself.

What I didn’t anticipate was how hard it is to actually find quinces. I went to no fewer than 12 grocery stores in Manhattan before finding any. I also learned from one fruit vendor that quinces are out of season in summer and are more likely to appear in late autumn. It struck me then that all I ever saw of the jam was the final product. If I, with all the resources of the internet at my disposal, was struggling, how had a deaf woman with barely any English managed to find a rare, and out-of-season fruit for her grandson’s birthday? What other tedious lengths had she gone to just for me?

Once I had them, I was faced with an even more difficult task that stemmed from the history of the quince itself. Because the fruit is beloved by so many cultures, there are countless different versions of this recipe. Even in Egypt one might have found the vastly different crimson Egyptian variety alongside the brickish Spanish paste. There is no single, codified grandma recipe handed down by the cooking gods at America’s Test Kitchen, as there might be for something like strawberry jam. I spent hours watching Egyptian and Portuguese grandmothers on YouTube, using Google translate to interpret Greek food blogs, but all too often the result was a dark, somewhat jellylike paste, so unlike the one I knew.

My grandmother was a woman who kept no records of anything, everything always ad hoc, free jazz, revised and improvised and reinvented at a moment’s notice.

The general ratio of sugar to fruit, spelled out in the pages of the popular preserve-making cookbook The Ball Book of Canning and Preserving, is anywhere from 30% to almost 100% sugar-to-fruit by volume, with about half an ounce of lemon juice per pound of fruit. One thing that almost all the Mediterranean grandmas of YouTube seemed to agree on was a ratio of one cup of sugar to one cup of diced or grated quince. Combining these two sources, I estimated that I would need about 400 grams of sugar to about 600 grams of quince, with 3/4 of an ounce of lemon juice.

To reverse-engineer my grandmother’s recipe, I also had to reverse-engineer other aspects of her cooking.

Often, recipes for quince jam call for boiling the seeds with the fruit because they contain a gelatinous compound called pectin. But not only was my grandmother’s jam looser than those I saw online, I also knew that her mother—my great-grandmother—would take the discarded quince seeds and soak them in water to make a kind of hair gel. Already I had my first clue.

The second clue came when my father remembered that when making carrot jam—which happened to be his favorite—my grandmother used a box grater. This is a popular technique for making quince jams. Quince is also an exceptionally hard fruit, and cutting it by hand would have been difficult for a woman in her 80s. The much more likely result would have been a trip to urgent care rather than a jar of jam.

This, as it turns out, was all wrong. Quince oxidizes quickly, even when soaked in water. Grating quince means that the yield often starts out a shade of brown much darker than the final salmon-rose of my grandmother’s jam. The result was a stringy and almost candied fruit paste.

My next approach was to imitate the techniques of the Mediterranean grandmas of YouTube by cutting the quince into even chunks roughly an inch big. As the fruit boiled in sugar water, gradually, I mashed them down into smaller pieces.

These cubed variants were also all wrong. The first was too firm and congealed, and far too sweet, with sugar masking the taste of quince entirely. In my next attempt, I cut the volume of sugar by half, which resulted in a fruit that wasn’t able to fully break down.

I spent two whole days failing again and again. In every version, the mashed quince, along with every surface in my kitchen, seemed to end up draped in a veil of sugary jelly because of the pectin from the stray bits of skin I’d accidentally left on the fruit. It also seemed that the other recipes greatly underestimated the amount of water needed, and in no time at all, my fruit was sticking to the bottom of the pan.

Knowing that I had to eliminate the extraneous pectin entirely, I methodically peeled my final batch of fruit. Hoping for a finer dice that would still break down in a lower volume of sugar, I sliced the quinces as if I were preparing shingles for an apple pie, and then cut the slices again perpendicularly. Even with a sharp knife, the toughness of the quince made these smaller cuts exceptionally difficult. The result was a series of very fine cubes. I put it to boil, mashed the softened fruit, and without much hope, left the stove alone.

Half an hour later, in the gathering dusk just after 6 p.m., before I even thought to check on the pot, I slowly sensed my apartment begin to swell with a sweet and long-forgotten vapor. It was a smell so familiar to me, so distinct that at the faint hint of it, suddenly years of autumn days came back to me. I went to the stove and saw a blush of orange-pink across the fruit. I did not even have to taste it to know that this was it. This was my grandmother’s quince jam.

When I had set out to recreate my grandmother’s recipe, I imagined that because of her general imprecision in all things, the jam, too, would follow suit. I thought she was likely to have left some skin on the fruit and to have cut it into uneven chunks. This, perhaps, would reveal the singular charm behind her version—something that did not conform to the usual laws of jam-making. But the path back to her jam was through something so precise, so methodical that I hadn’t thought to pursue it except by desperation. Only by doing the opposite of what I thought she might have done had I arrived at the recipe. Here was a contradiction I could hardly make sense of; my grandmother was a woman who kept no records of anything, everything always ad hoc, free jazz, revised and improvised and reinvented at a moment’s notice, and then, when you least expected it, when all logic should have dictated otherwise, here was evidence of the deft and delicate handiwork of a skilled artisan. The thought delighted me; suddenly, years after her death, I had learned something new about her.

Alexander Aciman is a writer living in New York. His work has appeared in, among other publications, The New York Times, Vox, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic.