Reb Shayala’s Free Lunch

Orthodox eateries open their kitchens to mark the yahrzeit of a Hasidic rebbe known for feeding the hungry

Free lunch does exist. On the third of Iyar, which this year falls today on April 24, eateries across the Orthodox Jewish world open their kitchens to the public at no cost in honor of Reb Shayala, who passed away on this day. Endearingly called Reb Shayala by his followers, Rabbi Yeshaya Steiner (1851-1925) led tens of thousands as a Hasidic rebbe in the town of Kerestir, Hungary. His main work centered around hospitality: He and his wife, Sara, personally fed thousands of hungry people in their home, and he bestowed visitors with blessings for a sustainable livelihood.

Growing interest in Hasidic figures has resulted in more than increased visitation to their graves; in the case of Reb Shayala, his lifework has become an active legacy that others carry on today.

While decades after his death, the movement of Reb Shayala now spans many countries, the Hasidic rebbe had humble beginnings. His father died when he was only 3 years old, and his mother sent him off to study in Hungary with Rabbi Tzvi Hirsh of Liska at the age of 12. Yeshaya Steiner had no grand rabbinic pedigree, but while serving as a gabbai, or assistant rabbi, to the Liska rebbe, he gained recognition as a miracle worker (most famously distributing bread rolls from an empty sack). After the Liska rebbe died in 1874, Reb Shayala followed the guidance of Rabbi Mordechai Leifer of Nadvirna to marry Sara Weinstock and move to the small town of Kerestir (otherwise called Bodrogkeresztúr), where tens of thousands of Jews eventually joined him in his court.

The stories that circulate about Reb Shayala emphasize his consideration for others, especially when supplying people with food to eat. On Rosh Hashanah, when services in synagogue are especially long, Reb Shayala could be found cutting slices of cake for the thousands of guests present. Even on his deathbed, Reb Shayala asked for fresh, hot food to be prepared; he wanted to ensure that there would be food to eat when people returned from his funeral, hungry. His blessings resulted in miracles: A woman who endured the Holocaust attributed her survival to a pair of earrings consecrated by Reb Shayala, and the mice infesting a Jew’s granary desisted as soon as Reb Shayala commanded them to leave.

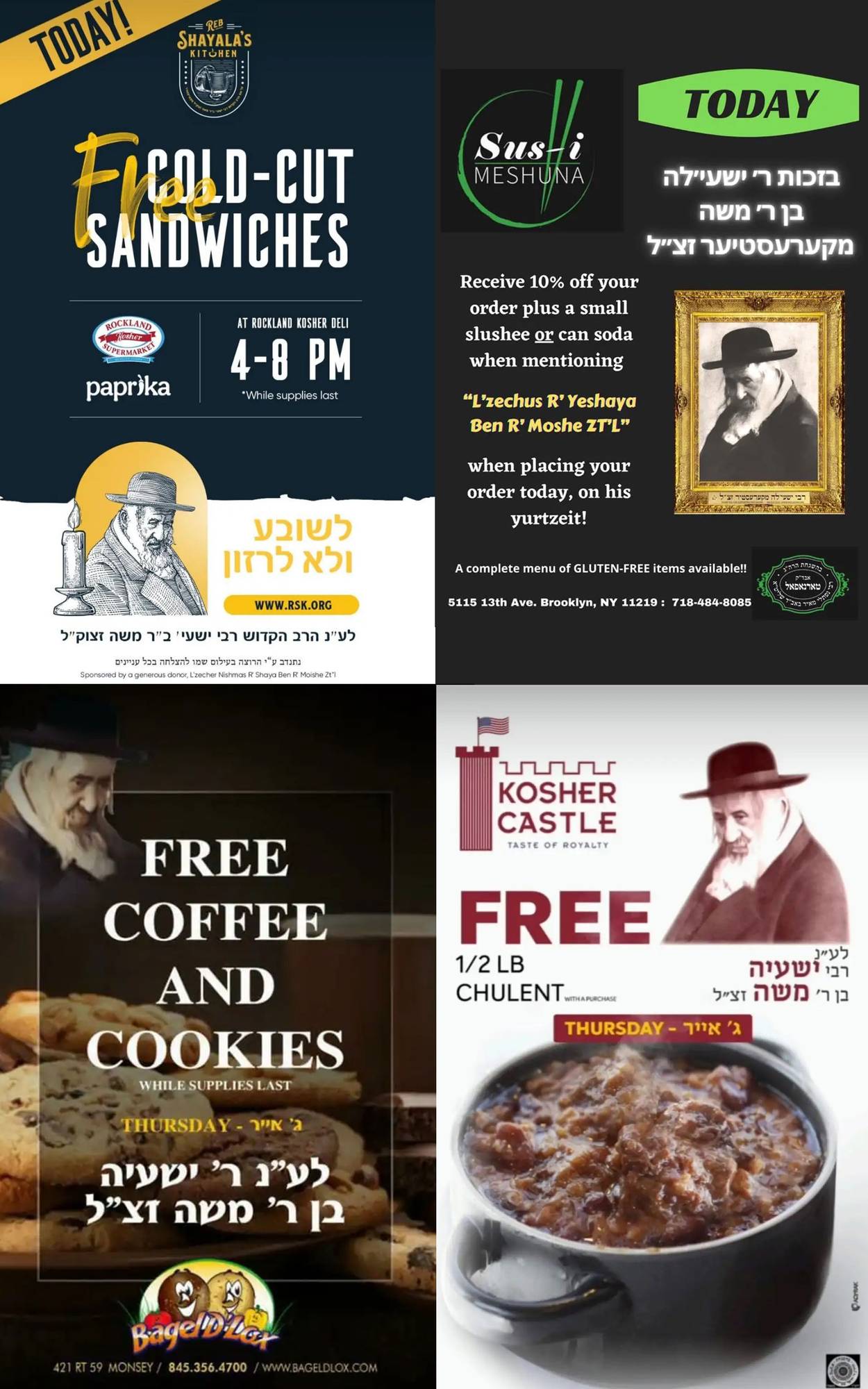

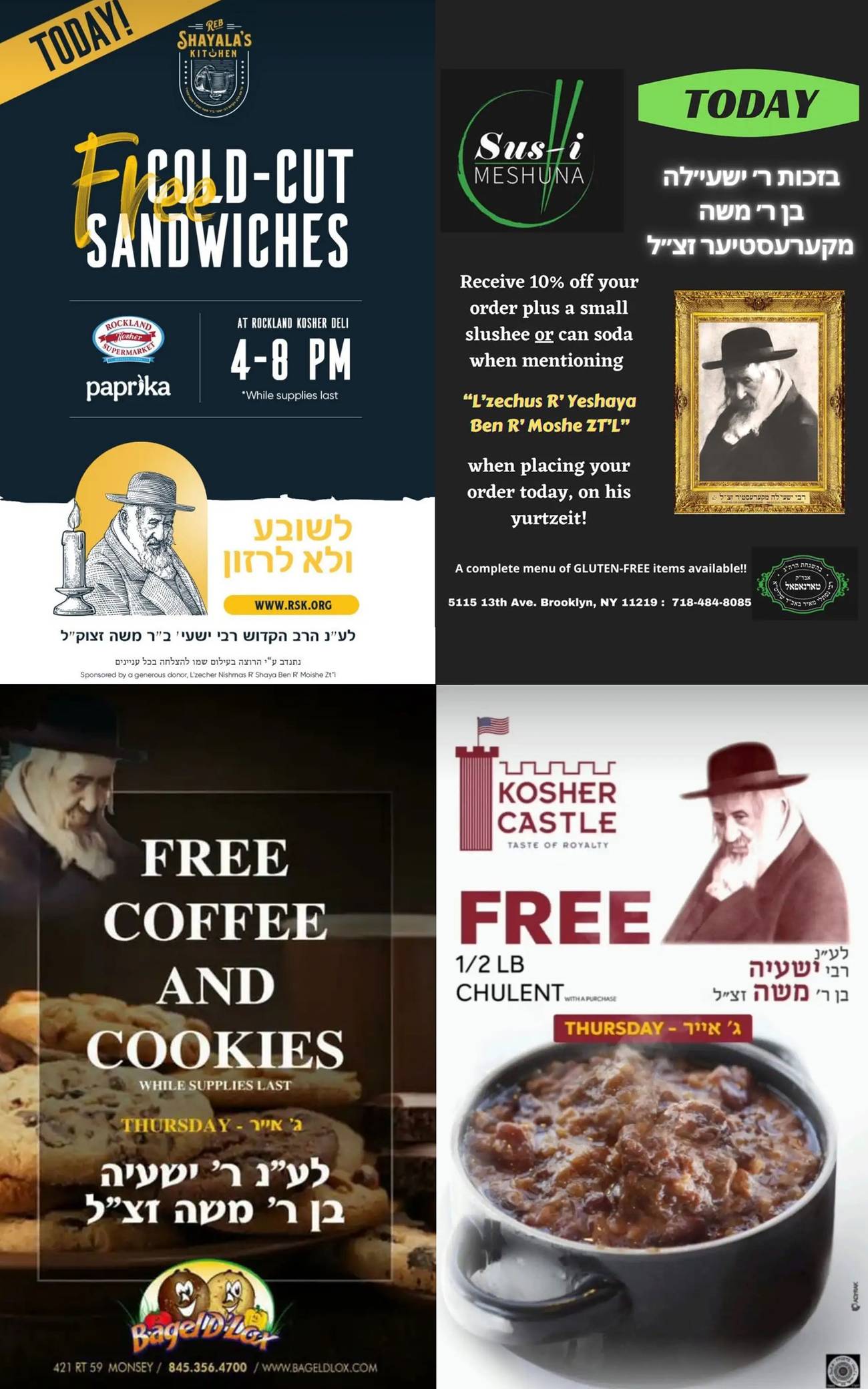

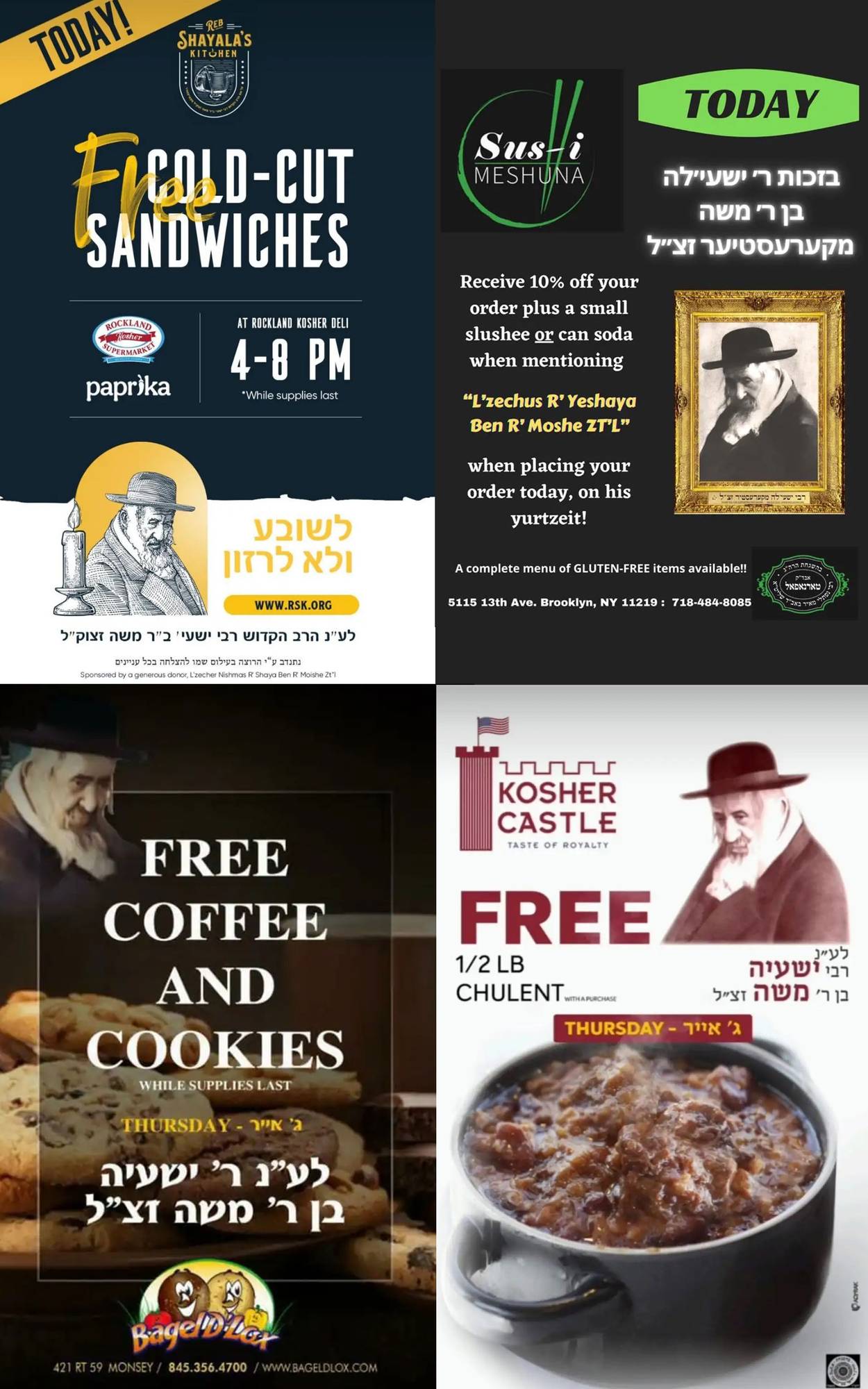

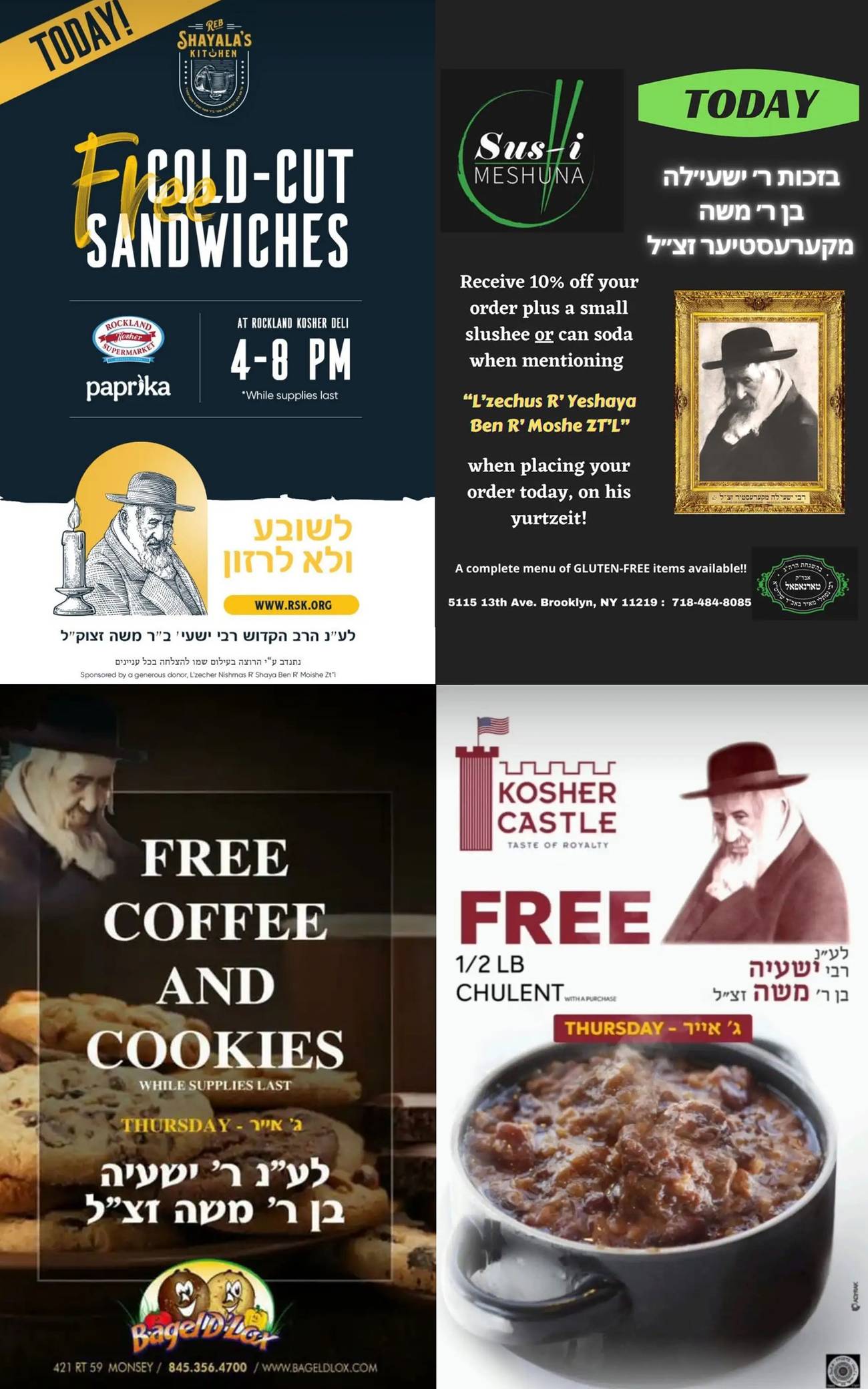

Last year, on the third of Iyar, I followed a stream of advertisements directing me to the various locations where free food was offered in my hometown of Monsey, New York—partly hungry, but mostly interested in observing the scene. The yahrzeit of Reb Shayala has become a day of commemoration across the Jewish world, characterized by unconditional giving of and connecting through food. Waiting on a long line to receive free food, I was initially mortified at my purported predicament. However, the practice of waiting for a handout brought a realization: Some people experience this feeling daily, and those carrying on the work of Reb Shayala are there to help.

My first stop was Leil Shishi, a diner that specializes in Shabbos cuisine and whose storefront is only open on Thursdays and Fridays. Sponsored by Reb Shayala’s Kitchen, an organization founded by Mattis Gilbert in 2012 that assists needy families, Leil Shishi was officially “open to the public.” The menu boasted every Jewish delicacy imaginable: two kinds of soup—chicken with noodles and matzo balls, and Yemenite beef soup—a variety of proteins including breaded chicken fingers, grilled chicken, glazed sesame chicken, tongue, and cholent, along with kishka and potato kugel. There was farfel, orzo, rice, green beans, and an array of brightly colored grilled vegetables. While the shop was mostly filled with young men—yeshiva students in white shirts and black suits—Sruli Goldberg, the owner of Leil Shishi, called out: “Ladies, ladies to the front!” so that mothers could bring home dinner for their children.

My free food crawl continued. Nussy’s Cuisine, a deli, welcomed customers to “pick up a free slice of potato kugel” in memory of Reb Shayala, and both KC Grill and Kosher Castle were distributing free hot dogs. Ático, a fine dining restaurant, publicized itself as “an open kitchen for all of Monsey.” Across my social media feed, I received notifications that a pizza lunch was sponsored in commemoration of Reb Shayala’s legacy at B&H, a Hasidic-owned electronics department store in Manhattan, and even more notices that bagel shops and cafes in the tri-state area were giving out free bites. These eateries invited people to make a blessing on the free food l’ilui nishmas, “to elevate the soul,” of Reb Shayala. After all, since the Hasidic rebbe could no longer fulfill God’s commandments in this physical world, others can perform them in his merit.

While many local Jewish shops open their kitchens to the public on Reb Shayala’s yahrzeit, there are several that support the mission of Reb Shayala year-round. For more than a year and half, Leil Shishi—in collaboration with Reb Shayala’s Kitchen, or RSK—has been providing approximately 200 families daily with a catered dinner. “If a family has someone in the hospital, or a new baby, or financially feels it’s a burden, they can get food,” Goldberg told me. Families in need reach out to RSK, and Goldberg takes care of the rest. “From Leil Shishi’s side, I feel like it’s a zechus [merit].”

Gilbert describes RSK as “a resource center to help middle-class people get back on their feet.” Inspired to found the organization after spending a Shabbos in Kerestir, he initially provided meals to struggling families until a mother called to tell him, “Ich bin a gezinte yiddishe mama [I am a healthy Jewish mother]. I don’t need the meals, I need the ingredients.” RSK expanded to temporarily subsidize weekly groceries to assist families with dignity. Now, RSK also offers financial coaching and career support. The mission of RSK is not simply to provide charity, but to guide families toward self-sufficiency. The resultant breadwinners often return to donate to RSK—the very fund that supported their turnaround.

Numerous other organizations across the world have also latched onto the legacy of Reb Shayala and propel his mission further. The direct descendants of Reb Shayala who live in Israel started a fund called Rav Lehoishia (a phrase drawn from the central Amidah prayer that is roughly translated to “the Powerful One [God] who delivers salvation”) that provides baby formula for families in various Israeli cities, runs a soup kitchen in Jerusalem, and hosts a weekly melava malka meal for young men from abroad who are studying in Israel.

Another fund that helps families put food on the table was established in 2013 by Shimon Charach, a Brooklynite. Instead of letting the untouched, fresh leftovers from local delis and wedding halls go to waste, Charach began to repackage the food for families in need. Within a few months, he was running a full-fledged organization with numerous volunteers for several hundred families. “I started the organization without a name,” Charach admitted. “But then I heard that Reb Shayala was somebody special that used to give out food. So be it, I said. I will put it under his name.” The organization was named Reb Shayala’s Kitchen, or Reb Yeshaya’s Koch in Yiddish (separate from Gilbert’s organization of the same name). Invoking the rabbi’s name serves a functional purpose in Jewish thought: Reb Shayala’s influence can sway the success of the organization from the realm beyond, especially since the charity is performed in his merit.

The model that Charach started in Boro Park has expanded to eight other locations: Williamsburg, Flatbush, Staten Island, New Square, Monsey, Monroe, and the Catskills—all in New York—and Lakewood, New Jersey. Each branch only accepts food donations, and has occasionally received trailer-loads of freshly packaged food from kosher manufacturers like Mehadrin Dairy and Stern’s Bakery.

Even though Charach did not know about Reb Shayala when he first launched his free food fund, he now organizes an event on the yahrzeit of the Hasidic rebbe. It has become customary (upon the directive of the late Reb Shayala, who appeared in a dream to one of his followers) that those who cannot travel to Reb Shayala’s grave in Kerestir can visit the grave of his brother, Reb Yehuda Tzvi Steiner, in Staten Island instead. Since 2018, Charach organized the annual event in Staten Island—which more than 7,000 visitors attend—bringing candles, prayerbooks, and of course food, which is either ordered from local takeouts or cooked in the home of the old Satmar rebbetzin. “This year,” Charach said, “we are full force, preparing all the way.”

But those who can travel farther than Staten Island make their way to Hungary. Last year, more than 30,000 people from America, Israel, and elsewhere flew to Kerestir to visit Reb Shayala’s grave on his yahrzeit, and there are multiple chartered flights available for both men and women who want to visit his grave this year. Many people flock to Reb Shayala’s Guesthouse in Kerestir, run by Rabbi Moshe Yosef Friedlander, which is the only kosher hospitality center in Europe to accept guests year-round and free of charge. The guesthouse notably provided Passover in 2022 for Jews in war-torn Ukraine, including 14 tons of matzo.

Avi Klein, a Hungarian Israeli who first visited Reb Shayala’s grave in 1991 and now lives in Budapest, also hosts many groups visiting Kerestir—oftentimes families that return to celebrate a long-awaited marriage. “You have to come twice,” Klein explained. “Once to ask, and once to say, ‘thank you.’”

Reb Shayala’s grave in Kerestir draws all kinds of Jews from around the world: religious, secular, Ashkenazim, Sephardim, Hasidim. “Most of the people who come feel something when they go into the ohel—even people who do not believe,” said Klein. He told me several stories of those who saw their requests granted, some almost immediately upon praying at Reb Shayala’s grave: “It works, people see miracles about many things. You can say it’s because of him, you can say it’s not. But in fact, it works.”

Even Reb Shayala’s picture has become an amulet. The slightly turned profile of the Hasidic rebbe donning a black platchige biber hat and a downward gaze—his long white peyos flowing into his beard, with a thick, white shawl wrapped around his neck and tucked into his black bekeshe—has become a universal commodity. Ever since the story spread of Reb Shayala commanding the mice invading a Jew’s warehouse to leave, the single existing photograph of Reb Shayala (reluctantly taken for a passport) has been plastered in homes and businesses as a segulah, or spiritual protection. (When I was a teenager at sleepaway camp, our bunkhouse featured his photo.) The image has been reproduced many times—ranging from small, laminated cards sold in Judaica stores to more sophisticated renditions created by Orthodox artists, including Yaeli Vogel and Shaindy Halperin. Halperin’s portrait of Reb Shayala, which sells for $2,800, was inspired by her personal visit to Kerestir, and she incorporates the rolling hills and signature vineyards surrounding the village into the painting. Even a non-Jewish Hungarian named Paul, who guards Reb Shayala’s grave, has the familiar image of the rabbi tattooed on his forearm.

Food brings people together, and the legacy of Reb Shayala continues to unite Jews around the world’s kitchen table even after his death. On the third of Iyar, as local bagel shops, bakeries, delis, and restaurants adopt the mantle of Reb Shayala’s service, the homemade taste of community-minded kindness ought to provide nourishment for the body and soul, if not food for thought.

Chaya Sara Oppenheim is editor of The Shekel, a numismatic journal. She holds a B.A. in English and history from Barnard College.