The Recipe for a Sweet New Year

As Russian Jews, our family always celebrated Novy God—and we always did it by baking my favorite cake

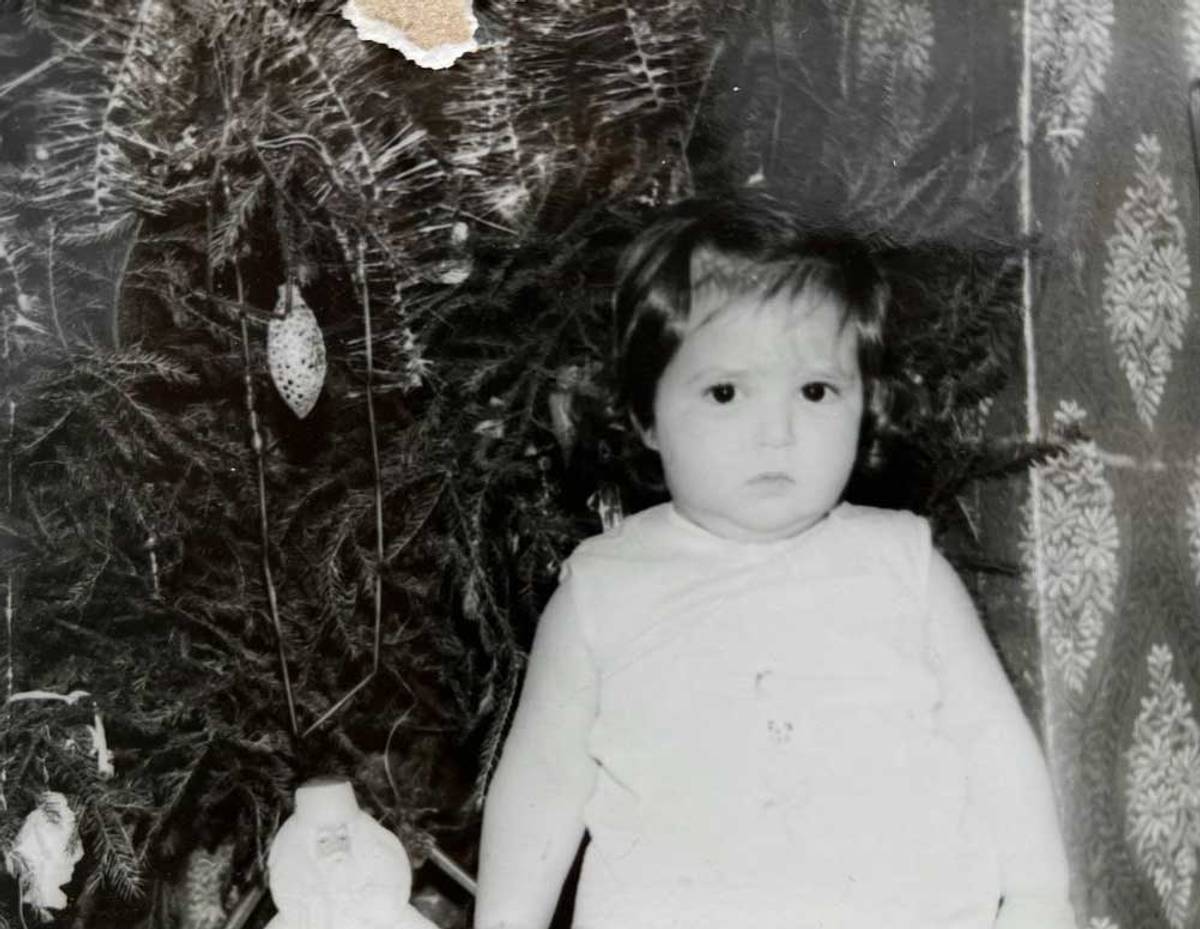

For the last few weeks, my 7-year-old daughter has been asking with increasing regularity, “Mama, when is Christmas?” I respond with a mental “facepalm” before I remind her that we’re Jewish, we live in Israel, and don’t celebrate Christmas. But she is a fan of Peppa Pig and a host of American-based YouTubers, so a lot of important people in her world celebrate Christmas.

To be fair, though, it’s not entirely Peppa Pig’s fault she’s confused. Because we do celebrate something around that time of year that to the untrained eye might look like Christmas. As Russian Jews, we celebrate New Year—Novy God. Now that I think about it, I’m not sure if my daughter, who is growing up trilingual, knows how to say “Novy God” in English or “Christmas” in Russian—or any of these in Hebrew.

Novy God is a secular holiday that is celebrated on Dec. 31. Like Christmas, it emphasizes family and gift-giving (on Novy God, presents are placed under a tree by DedMoroz—Grandfather Frost). But unlike Christmas, there is no religious backstory whatsoever: Families simply get together to greet the New Year. Novy God celebrations in Soviet schools involved children dressing up as snowflakes and dancing around a tree, or staging a play about helping Ded Moroz fight an evil force (e.g., Snow Queen) who wanted to prevent the beginning of the New Year and impose an eternal Russian winter. Outside of Soviet schools, Novy God is simply about getting together with family, greeting the New Year, eating nostalgic festive foods, and watching nostalgic movies.

Unlike my daughter, who is mostly looking forward to presents, I have a complicated relationship with this holiday, but there is one thing I definitely look forward to: getting together with our family and eating Kutuzov, our family’s special cake.

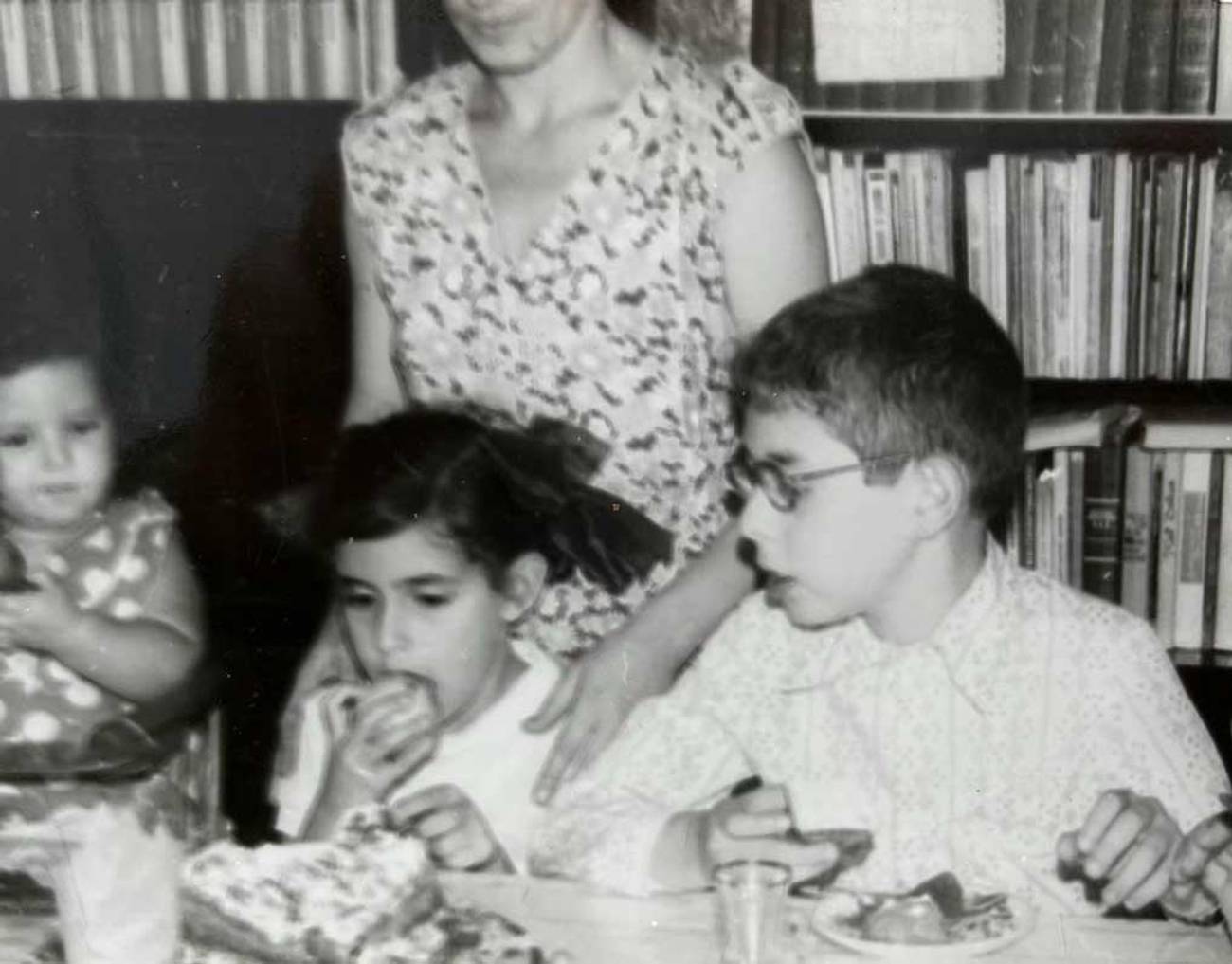

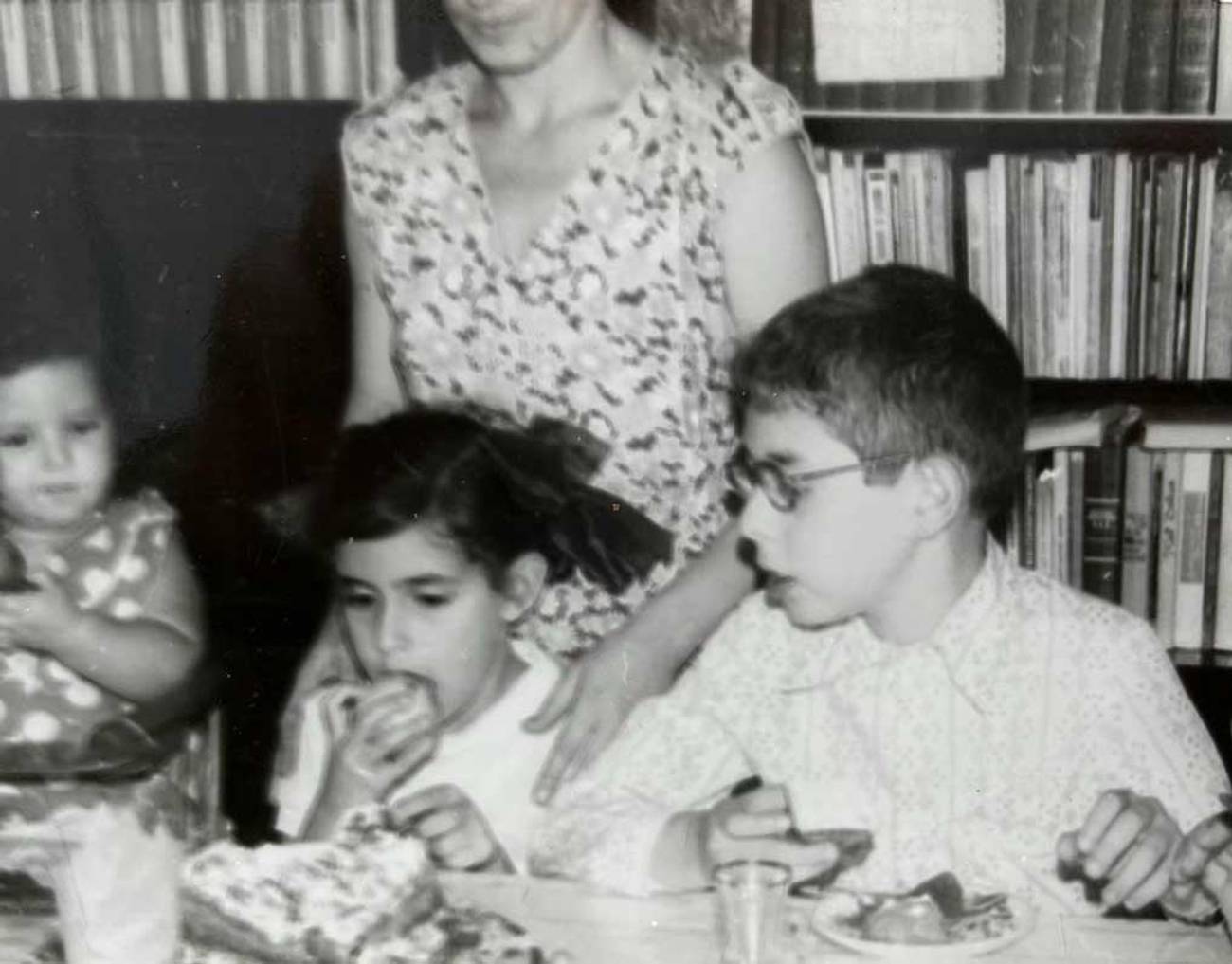

Every December of my childhood, our house would slowly fill with an impending aroma of celebration. We were a family of seven people: four siblings, two parents, and one grandmother. That meant we got to eat Kutuzov eight times a year: seven birthdays plus Novy God. Novy God was special not only because it was our most important holiday of the year, but because we had no birthdays between November and April, making it our only cake-eating opportunity in the midst of the cold and gloomy Russian winter.

Back in the Soviet Union, where we subsisted on boiled potatoes (occasionally with butter) and chicken feet, this cake, which contained such exotic ingredients as honey, walnuts, and orange zest, was nothing short of a miracle. Even in those times when we had nothing (my sister and I once got into trouble for making lollipops out of sugar and water because we used up the family’s weekly supply of sugar) we still had Kutuzov.

My family has been making this cake for generations, but I haven’t eaten the likes of it anywhere else. It’s called “Kutuzov” apparently after a Russian general who defeated Napoleon—another (much more common but definitely inferior) cake made in Russia. I Googled “Kutuzov” and found a poor imitation that uses only one tablespoon of honey, no oranges, and hazelnuts instead of walnuts (blasphemy!). It’s also similar to Russian honey cake (an authentic Ukrainian dessert, which makes sense because my family hails from Ukraine) but again, that recipe uses no oranges, not enough honey, and includes dulce de leche. Most noticeably, these other versions include butter or oil while our Kutuzov doesn’t.

A special narrow cupboard in our Soviet kitchen contained all the ingredients for the cake: a jar of honey that we weren’t allowed to touch, and what looked to my hungry child mind like a gigantic bag of walnuts. You needed orange zest, which meant that my grandmother saved the peel of every orange ever eaten in our house, dried them, and eventually ground them. I can still see her crouching over the kitchen table, meticulously cutting the white bitter layer of each orange peel, sometimes cutting her fingers; orange peels drying on the windowsill.

Once the dough was made, it had to “rise.” This actually meant “sit in a bowl over a pot of hot water, covered with a towel and a blanket” and I thought the dough was having a hot bath. We weren’t allowed to run in the kitchen or open the door too many times so as not to disturb it.

Then came the big day, when it was time to layer the cake with frosting. We got to help our grandmother crack and cut the walnuts into little pieces, which was pure bliss, because finally, when she wasn’t looking, you could slip some of those coveted walnuts into your mouth. My dad would beat the sugar and sour cream with a special fancy electric beater and let us lick the bowl after the cake was covered.

After the cake was decorated, the magic would begin: the frosting penetrating (or not) into the layers of the cake and making them deliciously moist. Whether or not it happened—this magic was out of our hands, and up to a higher power—the cake would be eaten in its entirely, but my grandmother would still lament, the way of Jewish grandmothers everywhere: Ne propitalsya!—which is roughly translated as “it didn’t get soaked!”

The truth is that while my relationship with Kutuzov is a very uncomplicated relationship of pure love, my relationship with Novy God, ever since I left Russia, has been strained. In Israel, it has always marked us as “others,” and even though it is somewhat more acceptable now (my daughter’s teacher now asks me to send her photos from Novy God to share with her class), I’m still self-conscious about it.

While everyone else seem to have brought their respected Jewish traditions back from diaspora (the Ethiopians’ Sigd, the Moroccans’ Mimouna) we brought this very un-Jewish relic of the Soviet era that was invented by the communists to wean the public off any kind of religious holidays. It’s a paradox that now that we live in Israel and are free to celebrate real Jewish holidays, we still hold on to Novy God. It’s like a prosthetic leg that you don’t need anymore because now we have real legs, real Jewish holidays! Why hold on to anything even remotely Soviet, especially now that 2022 made it clear that the Soviet ideology is not just a great evil of the past?

I guess that’s because traditions are much less about whatever (crooked) history they come from (remember Thanksgiving?) and much more about connecting to our families and to the child parts of ourselves, and, yes, about food.

For a long time it felt like we mostly celebrated Novy God out of inertia, because my parents cherished the tradition of getting together and giving presents, and because their grandchildren grew up cherishing the tradition of getting presents. But things happened in our family that made me appreciate this holiday more. In December 2020, we couldn’t get together, of course, because of the pandemic, but we promised our parents that we’d celebrate later. We knew that they’d already set up the tree in their living room and barricaded it with presents. The “later” never came, though. In early January, my dad was hospitalized with COVID-19, and soon intubated. That winter it was pure torture to walk by the tree still standing in my parents’ living room, surrounded by unwrapped presents and not knowing whether my dad would get to see us unwrap them or not. My mom finally had us unwrap the presents one day when we came back from another hospital visit. Which was the right decision. My dad died on Feb. 9 and we weren’t sure what Jewish tradition says about dismantling Novy God trees during shiva.

At first, I was certain I would resent this holiday forever after. But the next year I found myself longing for it, and longing for the cake, which now felt simply like a way to celebrate our family.

So, in keeping with traditions, we’ll just continue eating sufganiyot for Hanukkah, cheesecake for Shavuot, and Kutuzov for Novy God. And in keeping with traditions, this year, like every year, when we get together to savor that honey-and-orange taste of togetherness, my mother, the way of all Jewish mothers everywhere will inevitably lament: Ne propitalsya!

Tanya Mozias Slavin is a writer and a linguist whose work has been published in Oprah Daily, Boston Globe, and Newsweek. Find her on Facebook or Twitter.