It might seem incongruous to include the word food in the title of a book about Holocaust survivors. Prior to writing this book, I would have agreed. I would think it insensitive, almost cruel, to discuss recipes in the context of such a horrific time when food was scarce and starvation prevalent. Yet after speaking to “my” survivors, I came to realize that memories of food led them to hope, and hope fed their resilience—hence the title. Thinking and talking about cherished food was not a reminder of what they did not have but created hope for what they might have again. Their food recollections provided foundation for them when they were in tenuous settings. It was a bond to those who longed for familiar tastes; it was a way to bring family back to life and bring life to those who felt lost. As we moved from story to recipe, I saw smiles return and clenched hands ease. Food memory is transformative; it is a thread that weaves through all our lives. For Holocaust survivors, it brought them back to happier times. So many remarked that talking about the recipe, the preparation and the gathering around the table bridged their former to their current life. They drew on a recollection of their mother preparing challah for Shabbos or baking a potato kugel for what might be their last Passover Seder together as a family. The constant in all the dishes they shared with me was they represent a memory of food that needs to be preserved. I quickly discovered that Jewish food is hard to define. I began to question, what really makes a food Jewish? To a Sephardic Jew (one who can trace their roots to Spain after the Inquisition), it is stuffed onions and chicken with okra that graced her holiday table. For a German survivor, it might be arroz con pollo and fried plantains that she learned to prepare as a refugee in the Dominican Republic, and for a Polish survivor, it is the coveted Shabbos dinner with chopped liver, matzo ball soup, and roast chicken. The answer to my question was, more accurately, what isn’t Jewish food? There were common features to survivors from particular regions in both their wartime experiences and their cooking style.

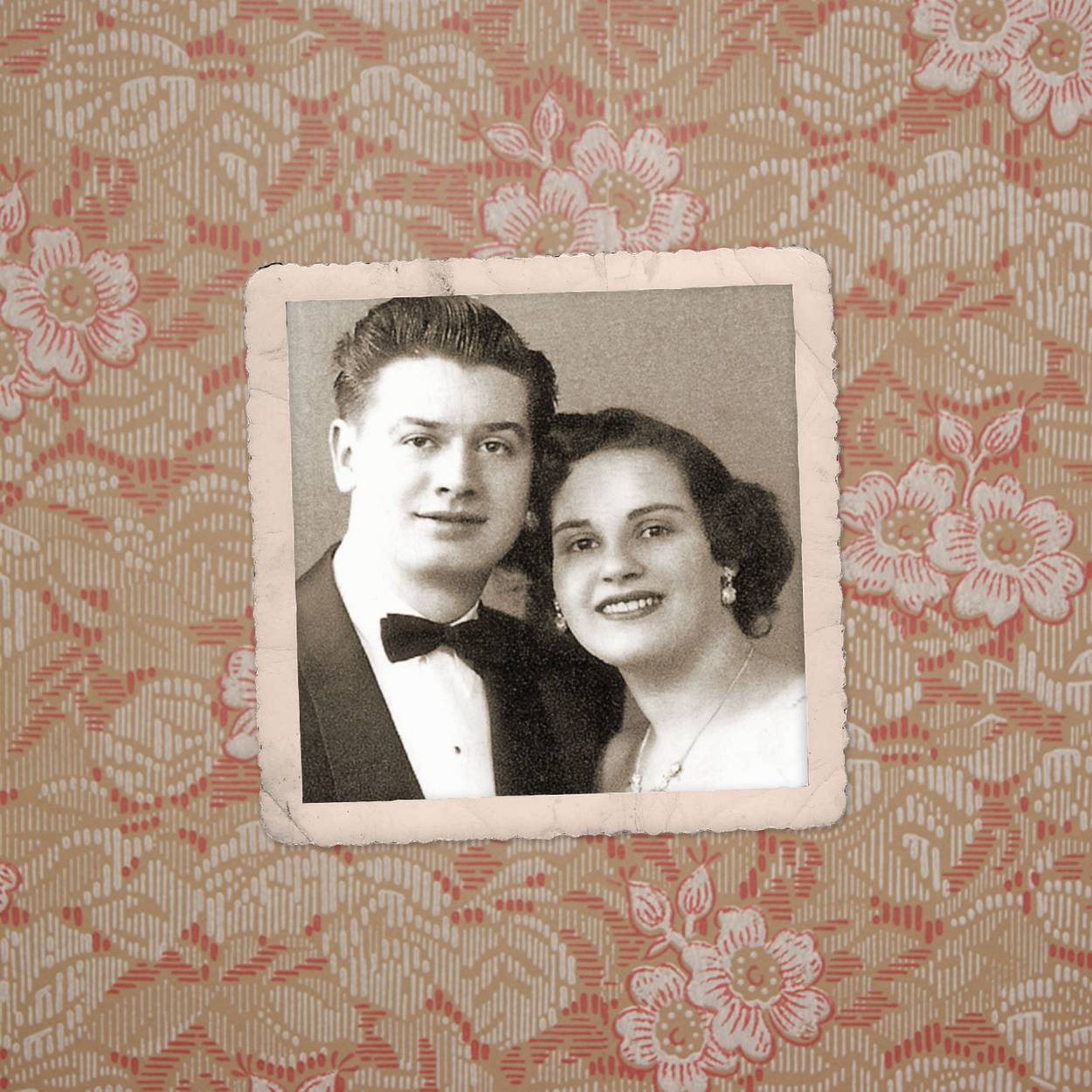

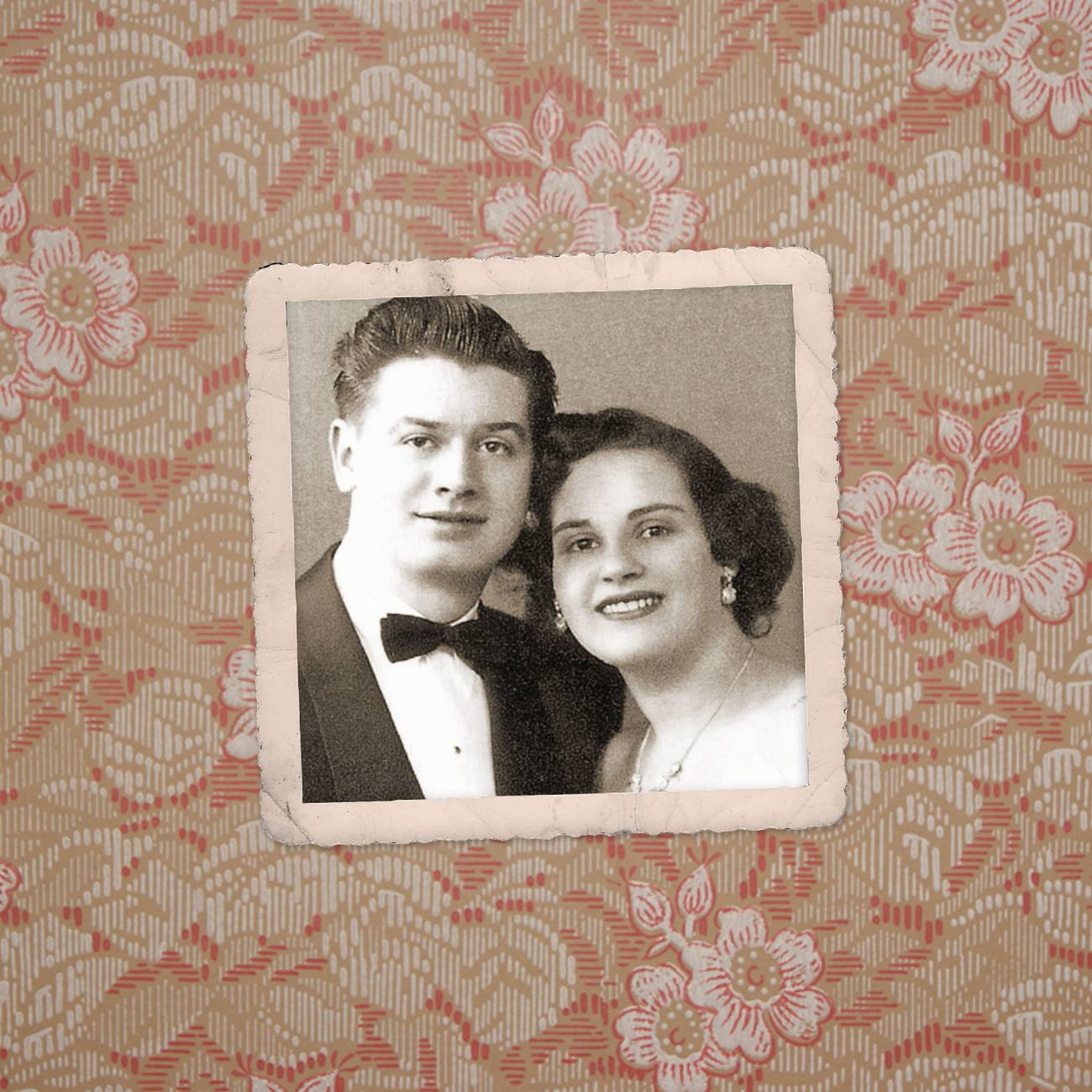

Jules Wallerstein

As told by his wife, Helen

Jules was one of the 937 passengers who boarded the SS St. Louis, presumably for safe harbor in Cuba. The fate of this ship has been the subject of books and a Hollywood movie titled Voyage of the Damned. The story of the passengers and their circumstances are still debated today. My husband, Jules, was born in Fürth, Germany. His father owned a jewelry store in town, which on Kristallnacht was ransacked and burned. His father was taken away for two days. Miraculously, he was returned. My husband’s family had a very successful cousin who lived in America; he owned Bosco, the chocolate syrup company. It was this cousin, Leo Wallerstein, who provided visas for the family to escape Germany. When my husband was 12 years old, his family and a total of 937 people boarded the SS St. Louis headed for Cuba. Although they had all filed for and received proper documents, only 37 people were allowed entry when the boat arrived on Cuba’s shores. When the bulk of passengers were not allowed to disembark, the ship’s Captain Schroeder sailed the boat within sight of Miami. Despite his hopes and the efforts of some members of the American government, the passengers were not allowed to enter the United States. The boat was ultimately turned away, and Captain Schroeder began desperately wiring other nations to see who would take these passengers. France, Holland, England, and Belgium all agreed to take a portion of the people on board. My husband’s family went to Belgium, and there he lived and even became a bar mitzvah. They lived peacefully with the Belgian people until the Germans invaded. Jules’ father went to the bank to withdraw their money and unfortunately was stopped and arrested. He was sent to an internment camp in France. Once again, his family reached out to their cousin Leo, and in 1942, they joined his father in France and then came to America. Three years later, now an American citizen, Jules was drafted into the army and sent overseas to serve as an interpreter and interrogator. He said it felt good this time “to be the one with the gun.” To my husband, this was another adventure in his life. In the year 2000, we received an invitation from the Watchmen for the Nations. They invited us to Canada to be part of a ceremony where the Canadians apologized for not accepting any passengers from the SS St. Louis. This same group sent us to Florida in 2001, where over 600 people gathered at the site where the ship had been anchored off the coast of Florida. We all said Kaddish (a prayer for the dead). It felt like the hands of the dead were reaching out. We then went with this group to Hamburg to see where the voyage began. We set out on a boat and reenacted the ship’s departure. On the edge of the coast, there were Christian Germans waving Jewish flags to honor the survivors. It was unbelievably emotional and moving; we could never have imagined such a sight.