The Waiter

He found success as an actor and a baseball player, but this may be the role David Mogentale was born to play

On a morning shortly after Christmas, David Mogentale was balancing two smoked salmon platters and a plate of latkes in his hands and screaming at a line of customers snaking through the store to get out of his way. The wait at Barney Greengrass, at Amsterdam Avenue and 86th Street, on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, is often up to an hour long, and those waiting can end up blocking the path of the busy staff.

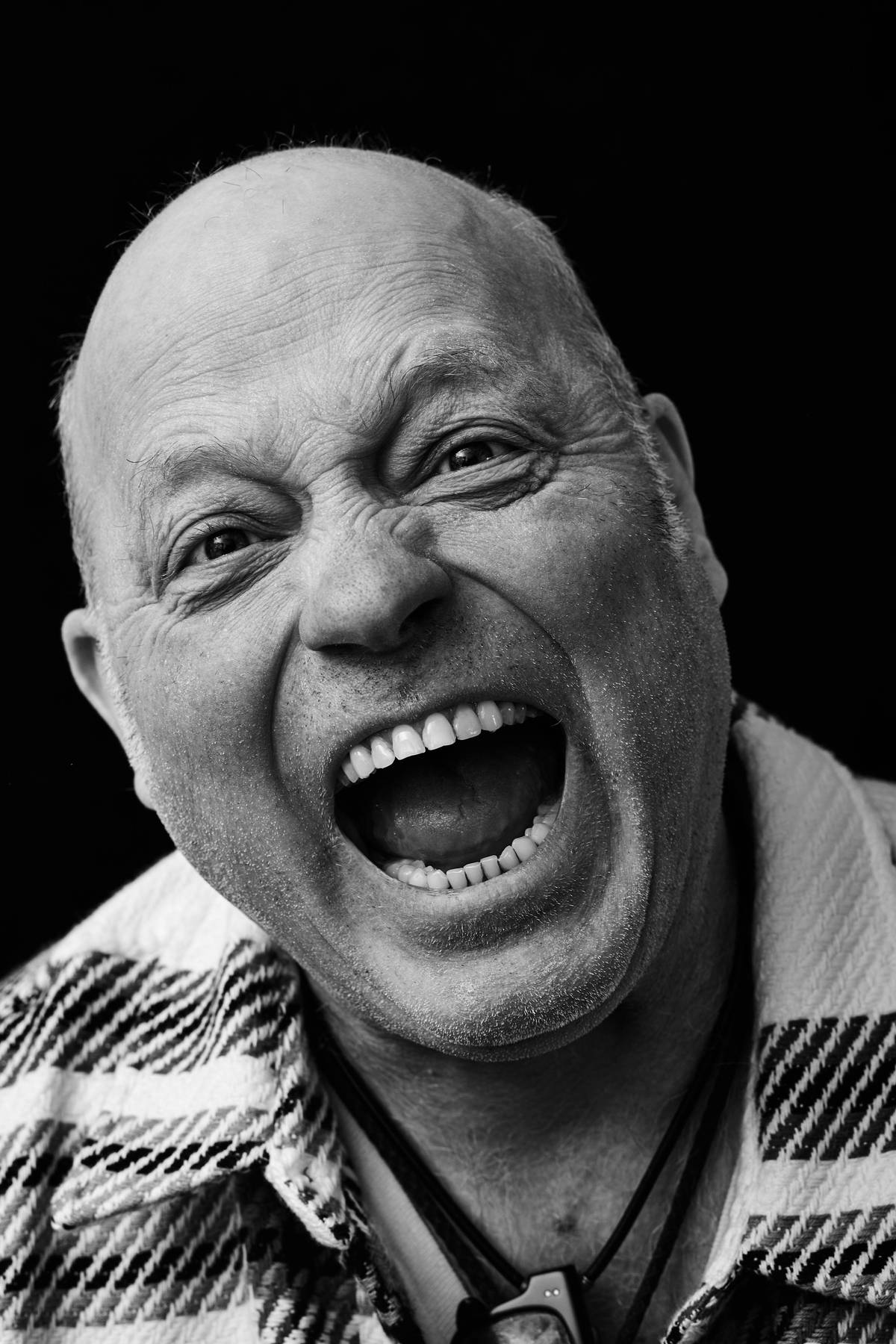

At 63, Mogentale is no longer in the same shape that made him a baseball star at Auburn. But at 6-foot-3, 230 pounds, his imposing physical presence is reminiscent of the actor who would serve as understudy to both Philip Seymour Hoffman and John C. Reilly in the 2000 revival of Sam Shepard’s True West. That Mogentale would also get cast as a drug dealer on Law & Order is not particularly surprising—his bright, aquamarine eyes and salty goatee suggest something slightly menacing. He wears a black Barney Greengrass baseball cap over a bald pate, his brown fringe neatly trimmed, and a white uniform on top and bottom with a pair of red Nike sneakers. Mogentale, known around Barney Greengrass as the Big Boy, has a talent for taunting and razzing the customers, while keeping them on his side. His methods have been developed over the course of decades and are exceptionally well-honed.

That same day, around the midmorning rush, a woman in a white, fur-lined parka with long blond hair cascading out from under a Yankees knit skully was telling Mogentale that he had to wait on her.

“We had so much fun with you last time.”

“I don’t remember you,” said Mogentale, tallying up a check on a waiter’s pad. “When was this?”

“Just about a week ago.”

“Yeah, well, no, I don’t remember. But you see that guy right there behind the desk? That’s the owner, Gary. Go up to him and say, ‘The Big Boy really makes the whole experience. I wouldn’t even come here if not for the Big Boy’—go up to him and tell him exactly that, word for word.”

Mogentale refers to his waiting style in the same way he does his acting: “brutal.” He so identifies with the term that it has found its way into the username of his email address: brutaljoe. The “joe” refers to Killer Joe, the eponymous character in the play by Tracy Letts, which Mogentale introduced to New York theatergoers in 1994 at the now defunct 29th Street Rep. Mogentale sees brutality as a kind of calling. Say the word and his eyes open wide and he comes alive, a devious and playful imp. In the highest grossing entertainment product in history, Grand Theft Auto V, Mogentale provides the voice of one of the stars, Nervous Ron Jakowski. It’s a voice that overflows with Mogentale’s playfulness, but also his passion for playing the role of the bad guy. Mogentale is Hobbesian by nature, but he is also an artist—an artist of the dramatic arts, and, unmistakably, of the Jewish dining room.

For the better part of the 20th century, a waiter at a New York Jewish eatery lived by his tongue: “What do you want?” “Hurry up, I don’t got all day!” “Here’s your check, now pay up front!” Kindness and patience weren’t his strong suits. Ask for more coffee, a clean fork, an extra slice of rye, and you would very likely never see him again. At the end of a meal, he would tell you it was a “real pleasure,” and then roll his eyes. But the death knell on this brusque, no nonsense, quip-happy waiter has been sounding for a while. In a 2006 article for GQ, Alan Richman said that the closing of Ratner’s, the iconic Delancey Street kosher dairy, marked “the end of the era of the professional Jewish waiter.” A blog operated from 2013-15 by David Manheim, a waiter at Katz’s Deli on Houston Street, was called “The Last Jewish Waiter.” Carnegie Deli is gone—Lindy’s and the Stage Deli, too.

Barney Greengrass is one of the few remaining appetizing stores from that bygone era when Jewish cuisine thrived throughout the city. The founder, Barney Greengrass, first opened shop on Amsterdam and 114th Street, serving smoked fish and pickled herring to local Jewish clientele. Thirty years later, New York state Sen. James J. Frawley would nickname Barney “the Sturgeon King.” Future patrons would come to include Franklin D. Roosevelt, Meyer Lansky, Zero Mostel, Jerry Seinfeld, John McEnroe, and Anthony Bourdain, to name a few. Over the next century, the décor would hardly change—Barney Greengrass could double as a museum dedicated to the refrigerators and display cases manufactured between the world wars—but the reins of ownership would be handed down through familial lines, first to Barney’s son, Moe, and then, following Moe’s death, to his grandson, Gary, the present-day owner. In 1992, Gary Greengrass hired Mogentale, an up-and-coming actor and onetime baseball star at Auburn University. While not Jewish, Mogentale can count himself as one of the last “Jewish” waiters. It is quite possibly the role he was born to play.

Barney Greengrass was far from Mogentale’s first waiting gig. After arriving from Pittsburgh in September 1983 and finding residence at the YMCA on 63rd Street, off Central Park West, for $60 a week, Mogentale worked at a discotheque on the East Side called Adam’s Apple, while studying acting at the New York Academy of Theatrical Arts. He finagled his way into a class with a casting director who had a competitive softball team by telling her he had been a star right fielder at Auburn. He dominated the softball league and was rewarded for his great bat and glove with a small part as a bartender on As the World Turns. (He shared screen time with Julianne Moore, Meg Ryan, and Marisa Tomei, all cast members on the show.) Mogentale got his SAG card. But for a while, no other roles came.

Meanwhile, Mogentale had taken up a new waiting job at Tavern on the Green, working doubles on Saturdays and Sundays. He soon discovered his penchant for overstepping the basic lines of fine dining: Knowingly serving the wrong dishes, making inappropriate jokes with customers, and, when necessary, ignoring them were all part of his waiting style. A diner who complained about the temperature of his steak found Mogentale pressing his thumb to the meat to see whether he was correct (according to Mogentale, he was not). The stunt led to his suspension. Mogentale relocated to Empire Diner on 22nd Street and 10th Avenue, and then to Memphis Restaurant on the Upper West Side, and then on to E.A.T., on Madison Avenue. One of his regular customers at E.A.T. was famed music attorney Allen Grubman, who took a liking to Mogentale. During the 1990 Christmas season, Mogentale, assuming a level of comfort with his customers that would become his trademark, wrote Grubman a poem.

Ode to a Melonhead

When the day gets dreary,

And hard to take,

When people are brutal,

And a smile harder to fake,

When the tempestuous artist is ranting,

Though we are not fully awake,

And the coffee is stale,

Not to mention the cake,

We look up to see Grubman enter the place,

A smile lightens the forlorn waiter’s pale face,

For Grubman brings a Yule-like tiding,

Great joy and good cheer,

And waits for a melon, sweet, plump, juicy, without peer,

When he has finished we all know one thing,

His charisma has changed us,

We almost can sing,

And just when he’s leaving,

Just before he has went,

The gruff murmur from that fine, gentle gent,

We strain to hear, our ears are all spent,

“Grubman,” he barks, “add twenty percent!”

Grubman loved the poem and told Mogentale that he would get him a job at a restaurant where he would earn a lot more money than he did at E.A.T. That place was Barney Greengrass.

“I went into Barney Greengrass,” said Mogentale, “and there was Moe Greengrass behind the desk. He told me, ‘Well, my son is taking over, and I like you, but he’s the one in charge of everything. And he’s the one who’s going to have to hire you. He’ll be coming in at 3, so, talk to him.’”

Mogentale interviewed with Gary, and he got the job.

At the time, Mogentale doubted he would last longer at Barney Greengrass than he had anywhere else. Why would he? And who cared? Waiting tables was just a way to pay bills while he waited for his breakout acting role, the one that would make him a star.

Mogentale was born in Pittsburgh, in 1959. His mother, Dolores, was a stay-at-home parent, raising Mogentale, his younger brother, and his sister. His father, Eugene, was an engineer at Ohio Ferro-Alloys, a metal producer. When David misbehaved (seldom), they would forbid him his favorite activity: going downstairs at 4:30 in the morning, as he did every day before high school, to practice hitting with his Johnny Bench Batter Up, a popular sporting good from the late 1970s that tethered a baseball to a batting tee in such a way that the ball circled back around to the hitter upon contact, allowing it to be struck again and again.

“That would really upset me. That was all I wanted to do, practice hitting.”

Every morning, after an hour and a half with the Johnny Bench Batter Up, Mogentale would go out in the rain and cold of western Pennsylvania and run up hills to increase his speed before the school bell rang at 8:15. As a child, Mogentale worshipped Roberto Clemente, the Pittsburgh Pirates star outfielder, and he was intent on becoming as great a ballplayer. But in an area of the country where rock infields with no grass were the only kind of baseball facilities to be found, colleges didn’t recruit, and he received no scholarship offers.

To this day, I don’t get why I never took a real shot at the big leagues.

He found a spot at Valencia College, one of the best junior colleges for baseball in the country, located in Orlando, Florida. After two years at Valencia, he went back home to Pittsburgh and considered his options. He didn’t have many. But a friend’s sister who played golf at Auburn University in Alabama agreed to talk to the baseball coach there on Mogentale’s behalf. To his surprise, he was invited down to the campus for a chance, albeit a very small one, of walking on to the Auburn team. By this time, Mogentale had a little bit of a resumé, having hit decently at Valencia. Without any promise of making the team, Mogentale still had to enroll at Auburn. During fall scrimmages his first year, he made the Auburn second team.

Between periods of success at the plate, he would fall into slumps. Frustrated, Mogentale went to a bookstore seven miles away in Opelika to find an instructional book on hitting. What he discovered was Charlie Lau’s The Art of Hitting .300. (Hall of Fame legend George Brett was a disciple of Lau’s and swore by his hitting approach.) Mogentale bought the book and read it cover to cover that night. The next morning, he set up his Johnny Bench Batter Up and began to practice hitting the Lau way: weight back, bat in the launch position, stride with front toe closed. At the next practice, Mogentale came up to bat, and on the first pitch he hit a shot back up the middle. Then he did it again, and again. For the next three weeks, Mogentale couldn’t miss.

“That book came to me—it was a God-like moment,” said Mogentale.

That spring, he got bumped up to the first team, where he ended up third in hitting with a .295 average. His great bat would continue into his final year, when he hit .348 and was named all-SEC. In his best performance at Auburn, Mogentale got five hits off Jimmy Key, the all-ACC Clemson pitching sensation who would go on to win World Series titles as a starter with both the Yankees and Blue Jays. (Mogentale did it with a broken finger, too.) One scout told Mogentale that he was the best pure hitter in Alabama. But Mogentale would go undrafted by the pro teams. He opted not to attend any open tryouts, a decision that still perplexes him.

“To this day, I don’t get why I never took a real shot at the big leagues,” Mogentale said. “I could have been a .300 hitter. I really believe that.”

Mogentale left Auburn after the 1982-83 school year. At 23 years old, he had only ever known baseball, and he was eager to launch himself into unfamiliar territory. He had always been secretly curious about acting and he began taking classes at a local acting studio. His teacher, Char Howard, got him a gig doing dinner theater in Pittsburgh. Though completely new to the dramatic arts, Mogentale liked the experience so much that three months later he moved to New York City to pursue acting.

It would take Mogentale seven more years in New York to discover 29th Street Rep, the company he joined in May 1990. Hungry to find great unknown plays, he traveled often throughout the Midwest, visiting small theaters. One bitterly cold night in the winter of 1993, Mogentale sank down into the back row of a 30-seat theater in Evanston, Illinois, to watch Killer Joe, a new play by an unknown playwright, Tracy Letts. (A 19-year-old Michael Shannon starred.) Mogentale was blown away by the tale of a Dallas police officer who moonlights as a hitman. He had a meeting with Letts the following day to discuss the future of Killer Joe. Letts told him that one of the reviewers, Hedy Weiss of the Chicago Sun-Times, called it the worst play of the year and that another, Richard Christiansen of the Tribune, said it was the best. Mogentale told Letts that he would like to put the play up in New York immediately, and Letts agreed.

Killer Joe was staged at 29th Street Rep in 1994 and created a lot of buzz for Mogentale, who played Joe. Casting director Bonnie Timmerman came in from LA to see a performance and met with Mogentale and Heat’s director, Michael Mann, about the actor playing opposite Al Pacino and Robert DeNiro in the iconic heist film. Although Mogentale didn’t get the part, the aura of Killer Joe hung around the actor. Broadway producer David Richenthal and director Robert Falls approached Mogentale about understudying Kevin Anderson in the role of Biff in the Brian Dennehy production of Death of a Salesman. Mogentale wasn’t interested in understudying, but the casting director called Mogentale three different times at his home, insisting he do it, and finally Mogentale agreed.

During every show, Mogentale brooded backstage; he would do anything to get on. But in six months of performances, Kevin Anderson, who would go on to win a Tony for the role, didn’t miss a single show. Mogentale says Richenthal promised him a real shot at playing Biff after Anderson’s departure. But Ron Eldard was brought on to replace Anderson, and Mogentale didn’t even get an audition. While Eldard prepared for the role, Mogentale was asked to star opposite Dennehy for two weeks of performances. “I wouldn’t do it,” said Mogentale. “I didn’t just want the two weeks. I wanted the part. And then I hadn’t even been given an audition after I had been told I would. It wasn’t right. So I walked away.”

The following year, Mogentale was cast as Philip Seymour Hoffman’s and John C. Reilly’s understudy in the revival of Sam Shepard’s True West. Mogentale had to be able to do both actors’ parts, Lee and Austin. He read for director Matthew Warchus and was hired. “I had just understudied in Death of a Salesman,” Mogentale said. “You get a reputation, having also done Killer Joe, and they think you’re good, even though you never even went on.”

To negotiate the role, Mogentale told his agent he wanted more money than anyone in the production save for the two stars, and he was given what he asked for, at $2,700 a week. But in early rehearsals, Warchus asked Mogentale to stay away from the theater altogether until the show was up. Mogentale believes Hoffman and Reilly didn’t want him around—maybe they were intimidated by him, or thought that he would be judging them. On a day before opening night, he was getting fitted for his costume. According to Mogentale, Reilly approached him and said, “Dude, what are you doing? You don’t need a wardrobe. You’ll never go on. We’ll never let you.” Mogentale said, “Oh really, what happens if you break your rib?” “We’ll still go on,” Reilly said, in Mogentale’s telling.

Indeed, Hoffman would break a rib and still not miss a show.

The True West job lasted eight months. Meanwhile, Mogentale was waiting tables at Barney Greengrass and working over at the theater on 29th Street producing plays. He landed a small part as Coach Goodwin in two episodes of The Sopranos. (Fans of the show will remember him making AJ captain of the football team.) Then, one day in February 2001, Mogentale was prepping for Sam Shepard’s Fool for Love at 29th Street Rep—it would be the play’s first revival, and the production was getting a lot of good press—and he couldn’t breathe. He had a severe cough, and worried it was pneumonia. He got a chest X-ray, and the doctors told him he had a 10-centimeter mass on his chest, growths in his abdomen and his lymph nodes. It was stage 3 leukemia.

Mogentale’s Sloan Kettering doctors urged him to do a bone marrow transplant, but he said no and took his chances with chemo. Living at Sloan Kettering for four of the next six months because of the intensity of the chemo—“more chemo than I’ve ever seen a patient get,” said one of his doctors—Mogentale was restless. From his hospital room window, he would look down on York Avenue at people riding their bicycles and wonder if he would get to ride his own bike ever again. Desperate to get out of the hospital, one day Mogentale decided he would sneak out, still in his pajamas, his face yellow and gaunt, rolling the metal pole on which his IV drip hung, and head uptown to his favorite brunch spot, the Vinegar Factory. Mogentale referred to this as one of the best meals of his life.

The chemotherapy continued for four years. Every so often, Mogentale would get a two-month break from the chemo and feel well enough to do a play. During this time, he did Fool for Love (2002), High Priest of California (2003), and In the Belly of the Beast Revisited (2004), about Jack Henry Abbot and Norman Mailer. Mogentale would beat the cancer, which stayed in remission after the four years of chemotherapy.

Mogentale gives a lot of credit to his wife, Carol. “She was an angel,” he said. “She took care of me. I doubt I would have survived if not for her.” After meeting at Memphis Restaurant in the late 1980s, Mogentale and Carol lived together for years before finally marrying in 2002. In framed photos hung throughout his one-bedroom apartment on West 75th Street, Carol is a striking figure, with long brown hair, a feline quality to her soft brown eyes, a lithe dancer’s body—she was a core member of the American Ballet Theater for over 10 years. “I always tried to figure out why she wasn’t a principal or a soloist,” said Mogentale. “People would talk about how good she was and how strong she was.”

In 2015, Carol, at 69, discovered that the breast cancer that she had fought off on three previous occasions had returned. When she got the news, Carol was also in the early stages of Parkinson’s disease. Physically and emotionally depleted, she did chemo for a few months and then decided to stop the treatment. According to Mogentale, she was in a lot of pain—more than she would ever tell him—and she just wanted to go. “There are certain things you want to ask somebody, things you don’t get to ask them. But then again, you don’t think the person is going to die the next day.”

The afternoon after Carol’s death, in 2016, Mogentale had a dental visit scheduled. He kept the appointment and got his teeth cleaned. Though Gary Greengrass would tell him to take as much time off as he needed, Mogentale didn’t miss a shift. “A lot of time, work grounds you, in that place especially,” he said. “We’re like a family at Barney Greengrass—a dysfunctional one, but a family nonetheless.”

Mogentale is still grieving. “After almost 30 years together,” he said, “I didn’t understand how difficult life was going to be all alone, without my wife. Every day when I walked in the door, no matter what, she would light up. Now I don’t have that smile. It is the absolute worst.”

The 29th Street Rep, Mogentale’s longtime theatrical home, closed in 2008, and he doesn’t have much acting work coming in. These days he is, more or less, just a waiter. For some 30 years he would only work weekends at Barney Greengrass, but he recently took on Thursday and Friday shifts, doubling his workload. Despite the toll on his body, Mogentale said he was happy to make the extra money. “And what else am I going to do? This is my only stage now.”

“Hey, Big Boy!”

A longtime regular, middle-aged, with a receding hairline, an oversize Jets sweatshirt and loose blue jeans, has walked in and seated himself at a table in the rear. It is 8:10 on a Sunday morning and the first rush is still 20 minutes off. The store has a kind of eerie calm about it, like an airport in the middle of the night. Without having to be asked, Mogentale has already written the regular’s usual order—Nova, eggs, and onions with egg whites only and a toasted, buttered bialy—on a white slip of paper and passed it through to the kitchen. Mogentale and the regular trade a few words about an upcoming football game, who would win, what were the Vegas odds, had either of them seen the last time the teams had played. Then Mogentale walks from table to table, straightening the cutlery, toweling off chairs, shining the salt and pepper shakers. When the food comes up, Mogentale serves it.

“Hey, Big Boy, can I get a real half-sour pickle? This one looks like a shriveled finger.”

“You know where it is—get it yourself!” snaps Mogentale, grinning.

Without hesitation, the regular stands up and goes over to the counter, doing as Mogentale has instructed. At the end of his meal, he leaves his usual $20 tip on the table.

“What can I say, they love the brutality,” Mogentale says with a laugh. “It’s why they love the Big Boy … he’s brutal.”

Julian Tepper’s work has appeared in The Paris Review, Playboy, The Daily Beast, The Brooklyn Rail, Zyzzyva, and elsewhere. His fourth novel, Cooler Heads, will be published in the winter.