Embracing My Whole Self, Through Food

I struggled with my identity as not-quite-American, not-quite-Israeli, until I learned a lesson from cookbook author Adeena Sussman

Gabriel Alcala

Gabriel Alcala

Gabriel Alcala

Gabriel Alcala

Growing up in New York City with an Israeli father and an American mother, I struggled with my dual identities, never feeling fully American, yet never feeling totally Israeli either. In the summer of 2018, when I was 30-something years old, I found myself in Tel Aviv trying to figure out who I was. Ironically, it was an American chef, cooking and writing about Israeli food, who helped me finally accept who I am and where I come from.

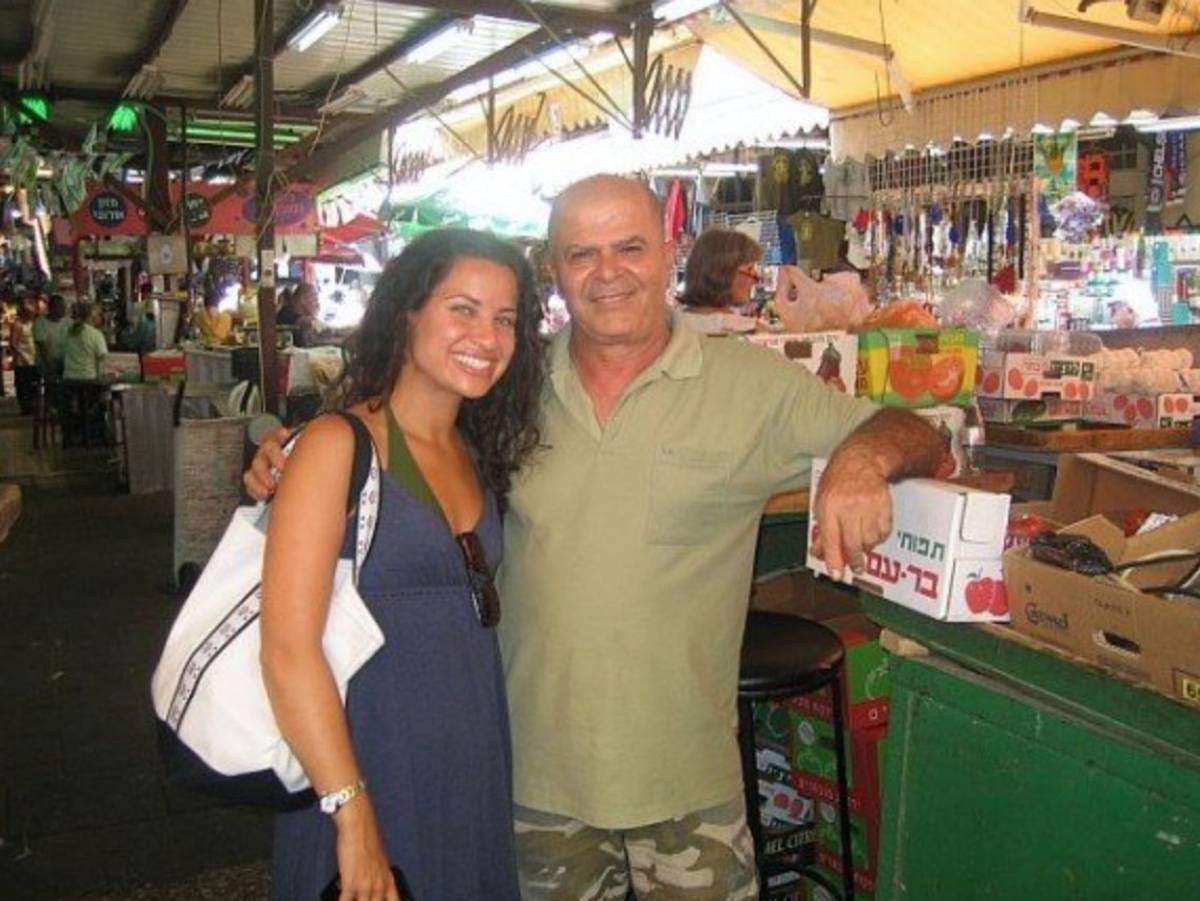

My father grew up in Tel Aviv, and he worked at his dad’s fruit stand—what Israelis call basta in slang—in the market since he was able to speak. Those stands were our family’s home base during our summer visits to Israel, and served as a reminder of where we came from. I grew up in the States, and always considered myself mostly American, and a bit Israeli. At home, all of our food was “ethnic,” and my parents definitely leaned into the Israeli parenting view on spontaneous play dates, as opposed to scheduling get-togethers far in advance the way my American friends did.

Even with my unease about my identity, I still found myself clinging to certain memories from summers spent in Israel as a child visiting my father’s family. Before even getting out of bed most mornings as an adult, I’d open Instagram and watch as chef and cookbook author Adeena Sussman would walk around the Shuk HaCarmel in Tel Aviv. I’d watch as she’d walk around, showing the fruit and vegetables stalls, saying good morning to all the shop owners, and occasionally passing my uncle Ezra selling the best strawberries in the market. It made me think back to the days of being a carefree teenager, wandering over to the market after a long, sweltering day at Gordon Beach to grab a fresh mango from Uncle Ezra’s fruit stand.

Courtesy the author

“Boker tovvvv,” Sussman would shout at the shop owners in her American accent. I’d usually roll my eyes. “Why is this very American chef the face of Israeli food?” I’d think to myself. And while I was a bit bitter, I was even more thankful that she was giving others, and especially me, an inside look into the beautiful, crazy world of Middle Eastern food.

On a whim during a brief visit to Tel Aviv in 2018, I messaged Sussman telling her how appreciative I was watching her daily tours through the market, how it brought me back to my childhood summers in Israel, and how she inspired me to write down some Middle Eastern recipes I feared would be lost once my father’s cancer took over. She responded: “Come over!”

I started sweating. Adeena was a stranger, and I am an introvert. I thought of writing back, “Oh just missed you, I’m already gone.” Instead, I stood and thought for a minute, and hesitantly responded, “Be right there!”

Just a few minutes later, we were sharing coffee and stories about our families. She told me about her move to Israel, and showed me photos of her upcoming cookbook. I looked over to the kitchen counter and saw half-prepared food.

“Did I interrupt you cooking? I’m so sorry. I can leave,” I said.

“Don’t be silly. Stay. Want to taste the fish I made?”said Sussman.

We sat, chatting for far longer than I expected, and both cried. She, too, dealt with cancer in her family and told me how she spent the last months of her mom’s life living with her, cooking for her, and learning her recipes. We shared stories about our weddings that took place just a few days—and 5,000 miles—apart.

That’s the thing about the culture in Israel. There’s an openness, directness, and warmth that simply doesn’t translate anywhere else. I told her that I would have never sent that message had I been in my beloved but hardened hometown of New York City. And she agreed: She would never have invited me over had she been back in New York. “Only here,” we said with a laugh. As I left her apartment and walked down the stairs of her building, I felt so thankful for Sussman, an American chef I had once balked at, for connecting me to my Middle Eastern culture.

One of the things that added to my identity struggle and feeling of “otherness” growing up was Shabbat dinner. Every Friday night, for as long as I can remember, my family gathered for Shabbat dinner in our home. My mother would begin cooking Thursday night, and when I’d wake Friday morning, the house was filled with aromas of garlic, cumin, and paprika. Looking back, having Shabbat dinner with my family every Friday night was one of the most special gifts my parents gave me. But back then, not being allowed to go out with my friends felt like a punishment. When I was young, I had to stay home on Friday nights. This meant missing sleepovers with friends, birthday parties, and dances. As I got older, I was allowed to go out after Shabbat dinner was over; when friends would pick me up, they’d comment how I smelled like garlic.

After meeting Sussman, my life got a bit hectic. My Israeli mother-in-law passed away, I had a baby, and my Israeli father passed away. In that order. A few weeks after my daughter was born in 2019, I saw that Sussman published a cookbook titled Sababa: Fresh, Sunny Flavors From My Israeli Kitchen, and would be speaking at my local bookstore in Brooklyn. It was my first solo night out after giving birth. I hadn’t spoken to Sussman since our meeting in Israel, but I knew I had to go. I bought Sababa, and we hugged and briefly chatted while she was signing books.

Sababa is a truly beautiful, inspiring cookbook, and while I did make a few recipes from it, I still felt apprehensive about having to learn recipes from my own Middle Eastern culture from a cookbook—specifically, a cookbook by an American chef. I felt uneasy about not knowing these recipes by heart.

This summer, when I heard Sussman was writing another cookbook, this one titled Shabbat: Recipes and Rituals From My Table to Yours, I knew I had to sit down and speak with her again. This time, over Zoom, we chatted about what it feels like to have dual identities, the concept of impostor syndrome, and how she hopes her cookbooks are received across both cultures—American and Israeli.

Originally from California, Sussman lived in Israel for five years after college, then moved to New York for the next 20 years. Toward the end of her time in New York, she met her now-husband on a blind date, and within a year she found herself back in Israel. After they got married, she made Israel her home.

“I see myself as an insider/outsider in a culinary culture,” said Sussman. “I’m an immigrant to Israel, but now, six years later, what I’m embracing is the duality of my identity.”

I shared my insecurities with her about what often feel like dueling identities: being part Israeli, but always feeling neither here nor there. We discussed my recent insecurities about my cooking, and kitchen, not really including the Middle Eastern foods I grew up eating.

Lisa Rich

“My goal is not to be 100% Israeli,” Sussman said. “My goal is to bring the most of myself, and the culture that I was raised in and not to mask those. We still make tuna melts in the house, and my husband and I both still love American comfort food. And even my approach to Israeli cooking definitely integrates how I was raised, and the kind of kitchen that I grew up in.”

The lessons I learned from my meetings and conversations with Sussman just multiplied. I was so used to grappling with who I am and where I come from that I didn’t stop to think about what I want to be, and how I want to lean into the rich cultures and traditions—American and Israeli—that shape who I am as an individual, as a mother, and as a chef in my own kitchen.

While Sussman does get a fair amount of accusations of cultural appropriation, she chooses not to get triggered, and to accept it as part of her story. “For me, I think the idea of being an outsider in a culinary culture is an advantage because it allows me to step back and see traditions, ingredients, dishes, and rituals in a way that people here [in the Middle East] might take for granted,” she said. “Moving to a new country gives you the opportunity to really frame your own identity. It forces you to look at who you are and what you’re about. I think that a lot of us live in extreme comfort and familiarity, and that we should try and think more like people who are living in uncomfortable and foreign places. Maybe that would give us more compassion, which I think the world really needs right now.”

Sussman and I talked a lot about the beautiful elements of Israeli culture: the openness, directness, the collectivist approach to society, and the extremely welcoming sense of hospitality. At the epicenter of Israeli hospitality is Shabbat. When Sussman was searching for an organizing principle for her new cookbook, she told me, she landed on Shabbat because it felt universal to people all over the world.

“I think people are waking up to the beauty of a time when we gather with family and friends to eat, enjoy, disconnect, and reconnect with our culture,” she said. “In Israel, Shabbat is the central focal point of the week, both from a social point of view and a culinary point of view. And I felt like this book could show people something beyond what they might know about Israel, sharing a window into the culture of weekend cooking.”

Discussing the beauty of Shabbat with Sussman gave me the assurance in my decision to often say no to Friday night plans so my little family of four can enjoy a Shabbat dinner together. Between preschool, work, and activities, our weeks feel very hectic these days. Now that I’m a parent, I miss—and crave—that feeling from childhood, when our world would slow down, and we’d all gather together at our table to eat Shabbat dinner. We don’t get to have Shabbat dinner every single week, but when we do, it feels so needed. Shabbat dinner gives us intentional time together as a family with nowhere else to be. It really forces us to slow down, plus I get to cook and share some of the foods my parents used to make at our Shabbat dinners.

My kids love the grape juice, challah, and “special” food Mommy cooks. But most of all, I think they love just being together. They’re still too young to have other Friday evening plans of their own, or know that there are events we’ve been invited to but declined. But when they’re older, and those challenges arise, I’m hopeful they still find joy in our Shabbat dinners, at least some of the time.

What I learned during my conversations with Sussman is that if she could feel confident enough to write and publish beautiful, thorough, and authentic cookbooks about Middle Eastern cuisine, and Shabbat cooking, then I could surely feel more secure in embracing my dual identities. I don’t need to be one or the other. It’s not so black and white. Some days I can feel more American, and some days I can feel more Israeli. Some days we speak Hebrew to our children, and some days we don’t. It doesn’t mean I’m an impostor, or confused, or anything more than someone who is made up of two distinctive, vibrant, and sometimes opposing cultures.

Become a member of Tablet and access special events, community conversations, and opportunities to connect with fellow readers.

Jamie Betesh Carter is a researcher, writer, and mother living in Brooklyn.