The Auto-da-fé of Mexico City

On Dec. 8, 1596, Luis de Carvajal the Younger, along with members of his prominent extended family of crypto-Jews, was burned at the stake. Their story has fascinated historians ever since.

This is a story of resistance and spiritual audacity. It is a story that unfolds in the deserts of Mexico’s silver mining regions, on the streets of the emerging colonial metropolis of Mexico City, inside the libraries of Franciscan monasteries, and in the underground cells of the Inquisition. It connects the far reaches of the Mediterranean Jewish diaspora with the global trade routes linking East and West. It is about colonialism, religious persecution, love, family, and faith but ultimately, it is a story about a book.

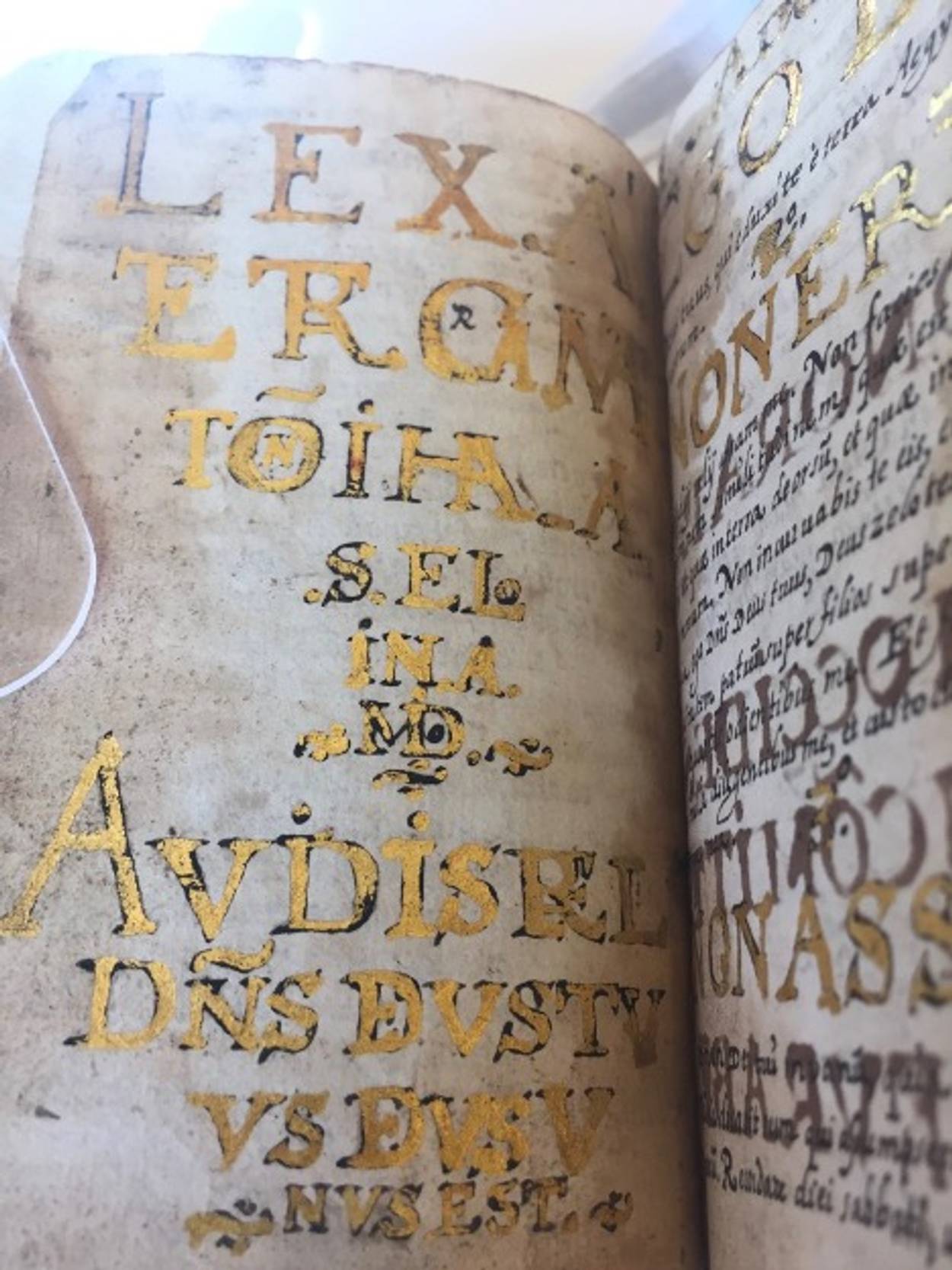

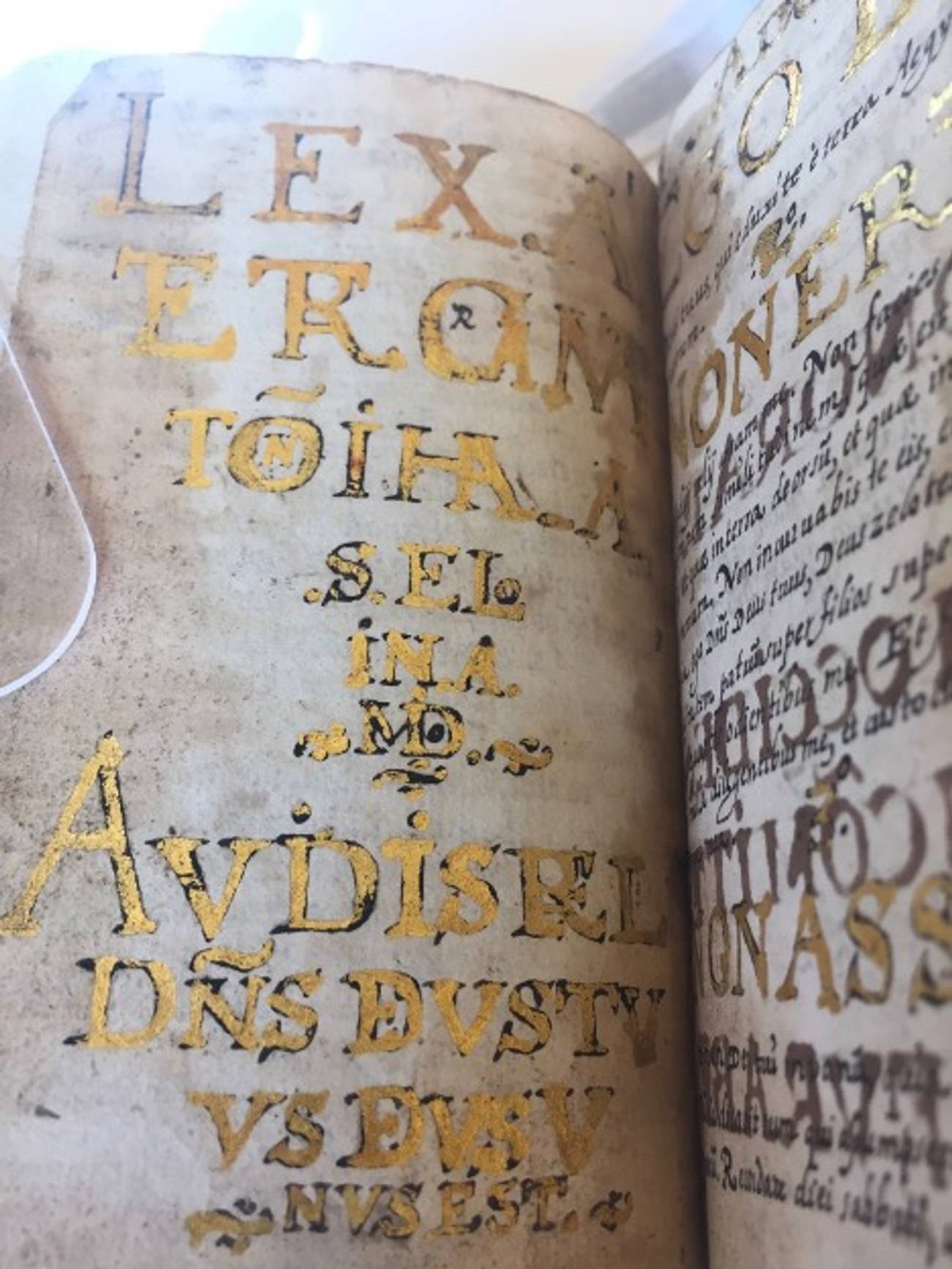

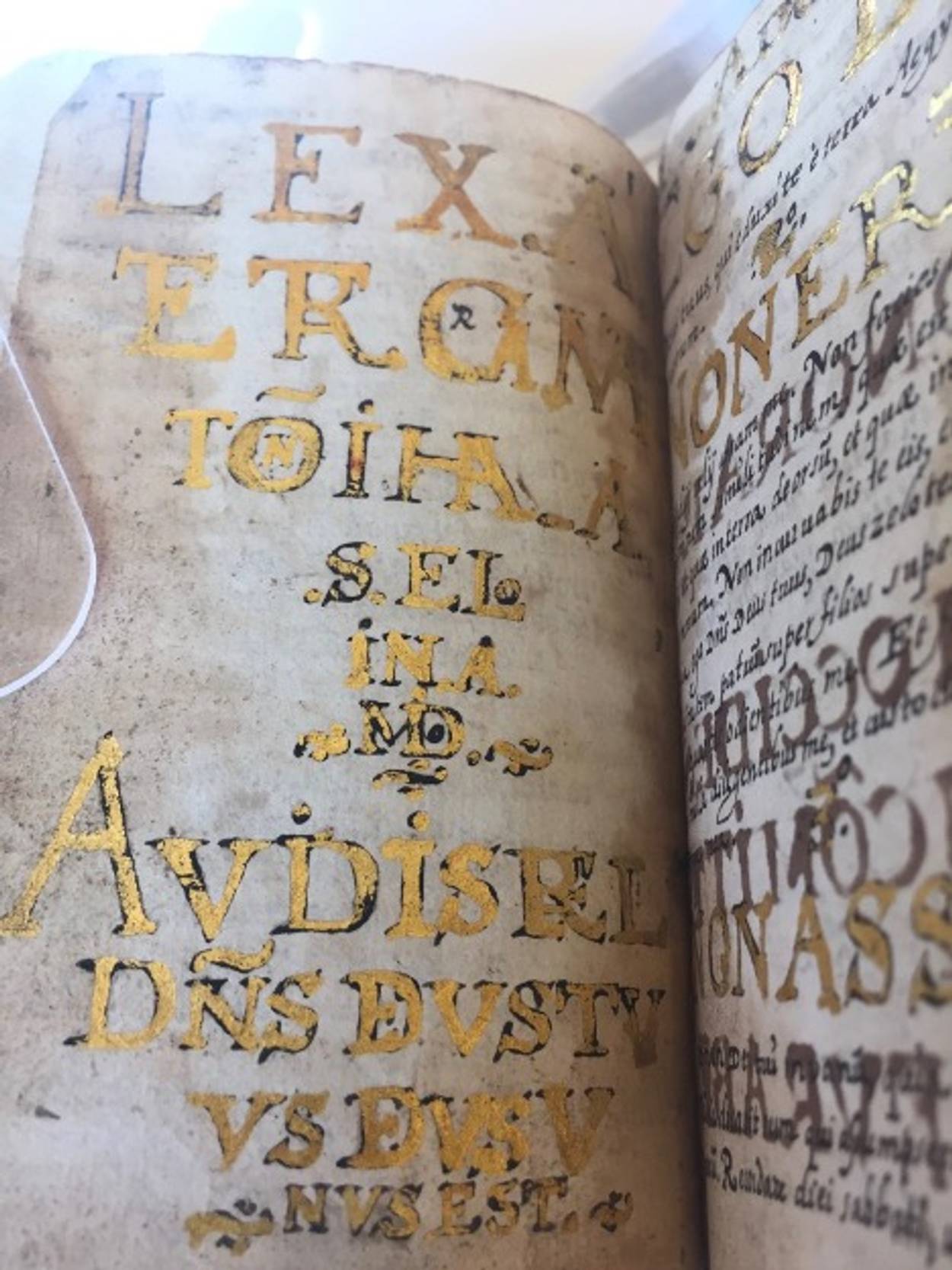

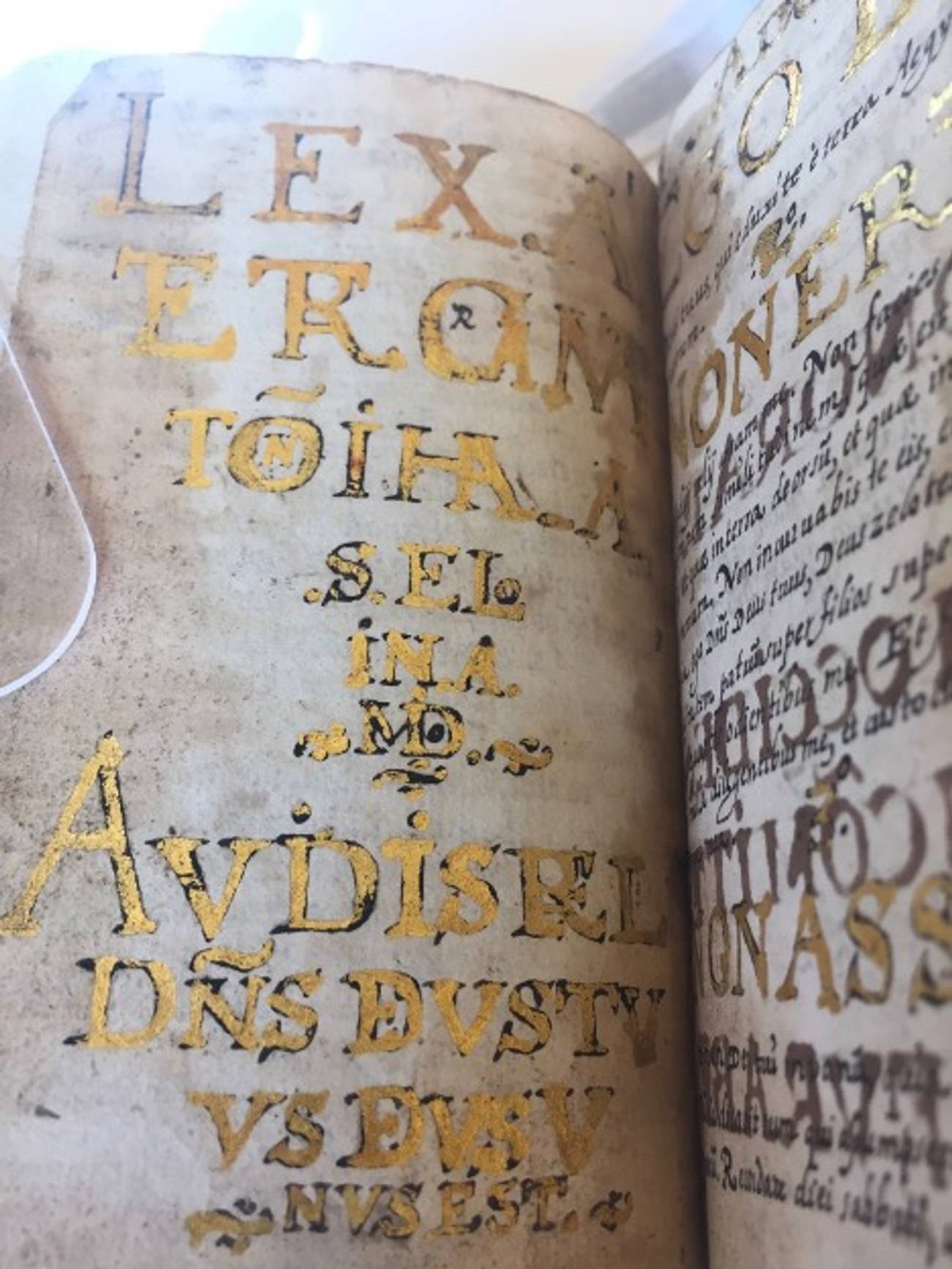

We begin with a small, leather-bound notebook filled with a highly original anthology: poems, prayers, meditations on the Ten Commandments, an electrifying autobiography, and even a holiday calendar. The book was written in the gifted scribal hand of Joseph Lumbroso, a 16th-century Mexican religious thinker, poet, and crypto-Jewish martyr, otherwise known as Luis de Carvajal, el mozo. Carvajal wrote this religious anthology in the few years between his two arrests by the Holy Office of the Mexican Inquisition for Judaizing. Shortly after his arrest, the book was found in his family’s home and was preserved as evidence against Lumbroso and his family on charges of heresy.

Heresy was a common accusation in this time, as was the crime of Judaizing—holding onto Jewish practices and beliefs. The Inquisition was focused on heresy, and as such sought to police the religious lives of Christians. But Spain had a large group of Christians who were, as their suspicious neighbors called them, New Christians. These descendants of Jewish converts were viewed by their Christian neighbors as less-than. They were seen as still deeply rooted in their Judaism and attached to the “dead law of Moses.” So the conversos entered the church by and large under duress—whether it was during the murderous riots of 1391, during the intense preaching campaigns of Vicente Ferrer, or when faced with the awful choice of abandoning their millennial home in Sepharad in 1492.

Once they converted, many sincerely embraced Christianity while others lived a double life, publicly comporting themselves as faithful Christians while secretly holding on to aspects of Jewish belief and practice. Regardless of their inner religious conviction, however, most conversos remained socioeconomically and culturally other. They continued to live in the same neighborhoods as before, worked in the same businesses, and continued similar marriage practices, namely marrying children into the family of business partners. No longer Jewish, now the conversos married their children to other conversos instead of other Jews. The court historian Andrés Bernáldez captured this succinctly when he described the atavistic Jewishness of the conversos:

You also have to know that before the Inquisition arrived, the customs of the ordinary conversos were the same as the same stinking Jews which is why they continually talked to each other. Thus, they were gluttons and comrades and they never stopped the Jewish customs of eating little dishes and stews cooked overnight on coals, little dishes of onions and garlic fried with oil … in order to avoid the pork … the other things they stewed smelled very bad on the breath, and their houses and doors smelled very bad from that food. Thus, they themselves had the smell of the Jews on account of the food that they ate … (translation from Lu Ann Homza’s Spanish Inquisition: 1478-1614)

Eating garlicky tapas drizzled in olive oil or preparing adafina is not an act of heresy. But for Bernaáldez the attachment to Jewish cuisine was a sign of cultural heresy. He goes on to refer to outright acts of Judaizing, such as keeping the laws of Passover and avoiding the Sacraments and then he turns to another sociocultural critique of the conversos Jewishness:

They did not believe that God rewarded virginity and chastity; their whole aim was to increase and multiply … Most of them were usurers who had many artful ways and tricks, because they all supported themselves from leisurely sorts of work in buying and selling they had no conscience where Christians were concerned. They never wanted to take jobs that involved plowing or digging or walking through the fields guarding flocks , nor did they teach their children, rather, they took work in town which involved sitting down and earning something to eat with little effort …

The conversos stood apart from the Old Christians as much by their marriage patterns, economic pursuits, and daily habits as they did for any actual acts of heresy. Being marked in this way meant that individual acts of heresy were seen as a social phenomenon and the conflation of converso with Jew. And this is why even though the Inquisition cared about Christians who engaged in heresy, in Spain the main target for such heresies were the conversos, those Christians who not too long ago were Jews and who still seemed to live like Jews.

This phenomenon took a fateful turn in Portugal in 1497. The largest single group of Sephardic Jews who chose to hold on to their faith and brave the unknown dangers of exile went across the border to Portugal. The country needed entrepreneurial merchants and financiers who could help manage their burgeoning trade with Africa and India. The Jews were welcomed into the class of Homens de Negócios (businessmen), which frequently was synonymous with the ethnic marker of Homens de Nação, Men of the Nation. Five short years later, the king forcibly converted this entire group of Jews and created a larger, clearly recognizable social type—the Portuguese New Christian merchant. These Portuguese New Christians soon found their way to the centers of international commerce in the Mediterranean, northern Europe, and the Americas.

In this swirling movement of people, goods, and ideas the secret practice of Judaism pulsed. Commitment to the Law of Moses was not universal, of course, and most Portuguese New Christians seemed to have been content to live their lives within the church. However, time spent far from the prying eye of the Inquisition, whether on the high seas, in a trading post on the West African coast, or in an Indian village in Zacatecas, allowed for furtive exchanges of prayers and rituals and revelations of the heart. Even several generations after the expulsion and the forced conversions one could still find conversos doing business and interacting with their cousins living in the safety of Juderías in Ferrara, Livorno, Salonica, or Amsterdam. Those Sephardic Jews that were able to fully embrace their roots often had financial or familial reasons to return to the” lands of idolatry” (as the Sephardim referred to Catholic lands where Judaism was forbidden). Crossing borders, these Jews smuggled their knowledge of Hebrew prayers, rituals, and general Torah knowledge into the lands patrolled by the Inquisition.

The Carvajals were representative of this global converso network. Luis de Carvajal y de la Cueva was born in Portugal and began his career trading along the African coast, where he was often involved in slaving expeditions. He eventually married the daughter of his Portuguese New Christian business partner and expanded his commercial activity to the Caribbean and Mexico, where he engaged in several military campaigns against the groups of nomadic tribes known collectively as the Chichimecos. In the early modern Iberian context, commerce carried the heavy scent of Jewishness. War against the infidel, however, whether it was against the Muslims during the Reconquista or the Indigenous peoples of the Americas during the Conquista was a distinctly Old Christian path to upward mobility. By throwing himself into the project of conquest and colonization, Carvajal was seeking to shed his converso past and remake himself as a New World hidalgo. There was just one problem—he needed his family’s help to reach this goal.

In 1579 Carvajal was rewarded for his success as a conquistador with the governorship of the Nuevo Reino De León. He needed a core group of settlers that he could trust to help him establish control of the territory, so he turned to his family back in Spain. They were granted an exemption from proving their purity of blood (limpieza de sangre) and allowed to join Carvajal y de La Cueva. He had no children of his own, so he looked to his two nephews, Luis and Baltasar as his trusted assistants. Together they patrolled the vast territory, supervising the mining areas and battling the Chichimecos. The governor also had plans for his unmarried nieces. He wished to marry them off to Old Christian soldiers, a move that would help cut the family’s ties to their converso, mercantile past and bring them closer to the landed gentry, the hidalgos that made up the humbler rungs of the New World aristocracy.

It is unclear how much the governor knew about the crypto-Jewish allegiances of his family back in Spain and Portugal. Did he know that his sister and brother-in-law and their older children were all committed to the Law of Moses? Did he know that the Portuguese doctor, Manuel Morales, who joined the original group of settlers, was well-known for his piety and vast knowledge of the secret faith? The list of individuals in the group with some level of commitment to crypto-Judaism was vast and varied.

Even his wife, Doña Guiomar, is identified as a passionate Jewess who shared her faith with his relatives when they stayed with them in Seville during the weeks before the journey to New Spain. Doña Guiomar never joined her husband in the New World, which shrouds their relationship and the role of her possible heretical tendencies in darkness. Nonetheless, it is clear that while Carvajal the governor saw the move to Mexico as a unique opportunity to place himself within the world of Old Christian respectability, his family’s crypto-Judaism had the potential to doom the entire enterprise.

The family settled in Tampico on the Pánuco River. The governor saw his nephew Luis as loyal and committed to the church, but while he would ride by his uncle’s side, Luis was increasingly becoming a fiery believer in the Law of Moses and the God of Israel. The governor’s plans for his nieces were thwarted when the family managed to secure their marriage to two converso merchants, Antonio Díaz de Cáceres and Jorge de Almeida. Gaspar, the Dominican friar, began to see more than he would have liked of the family’s secret Judaism on a return visit home to bury his father who died on one of his business trips to Mexico City.

And the eldest sister, Isabel, let her passion for the God of Israel overwhelm her prudence when she tried to spread the truth to another converso, who was so shaken and appalled by the idea of returning to the error of his ancestors that he reported Isabel and the rest of the family to the inquisitors.

This led to the arrest of almost the entire family, including the Governor Carvajal. He was convicted of harboring heresy after it became clear how much and for how long he knew about the family’s Judaizing. Yet he refused to turn them in. There was a good deal of political maneuvering involved in targeting the governor—he had recently fallen out of the graces of the viceroy, so the Inquisition’s prosecution of this once-powerful man served a rather mundane calculus of political expediency. The governor was stripped of his position and exiled for life from the Americas, where he died in jail before he served out his sentence. Baltasar and Miguelico evaded arrest and managed to escape to the freedom of Italy and eventually at least one of them was reported living as a Jew in Salonica. The matriarch of the family, Doña Francisca, along with her older daughters and her son Luis all confessed to their heretical crimes. They pleaded for the mercy of the Mother Church. At the auto-da-fé of Feb. 24, 1590, they were sentenced to penance and loss of property. They served out their penance working in various jobs in hospitals and monasteries around Mexico City.

Luis de Carvajal, el mozo, began to compose his religious anthology in the months and years following that first auto-da-fé. He drew on texts and experiences from before his arrest but also continued to add new ideas and sources into the religious writings that make up the book. He also took the events of his 25 years of wandering, (peregrinage) and transformed them into a biblicized narrative of God’s providence, where he was no longer Luis de Carvajal but rather Joseph Lumbroso. As his life story unfolds in the anthology, we can see his Joseph-like qualities develop. We can also see how his Jewish surname of Lumbroso, meaning the luminous or the enlightened, shades his prophetically charged autobiography. He writes about himself in the third person. He is a dreamer, someone who receives divine messages, who sees the hand of God in all matters, great and small, and who can read sacred texts with lucidity but also turn the events of his life into a providential narrative that echoes the rhythms of the Bible. He becomes biblical.

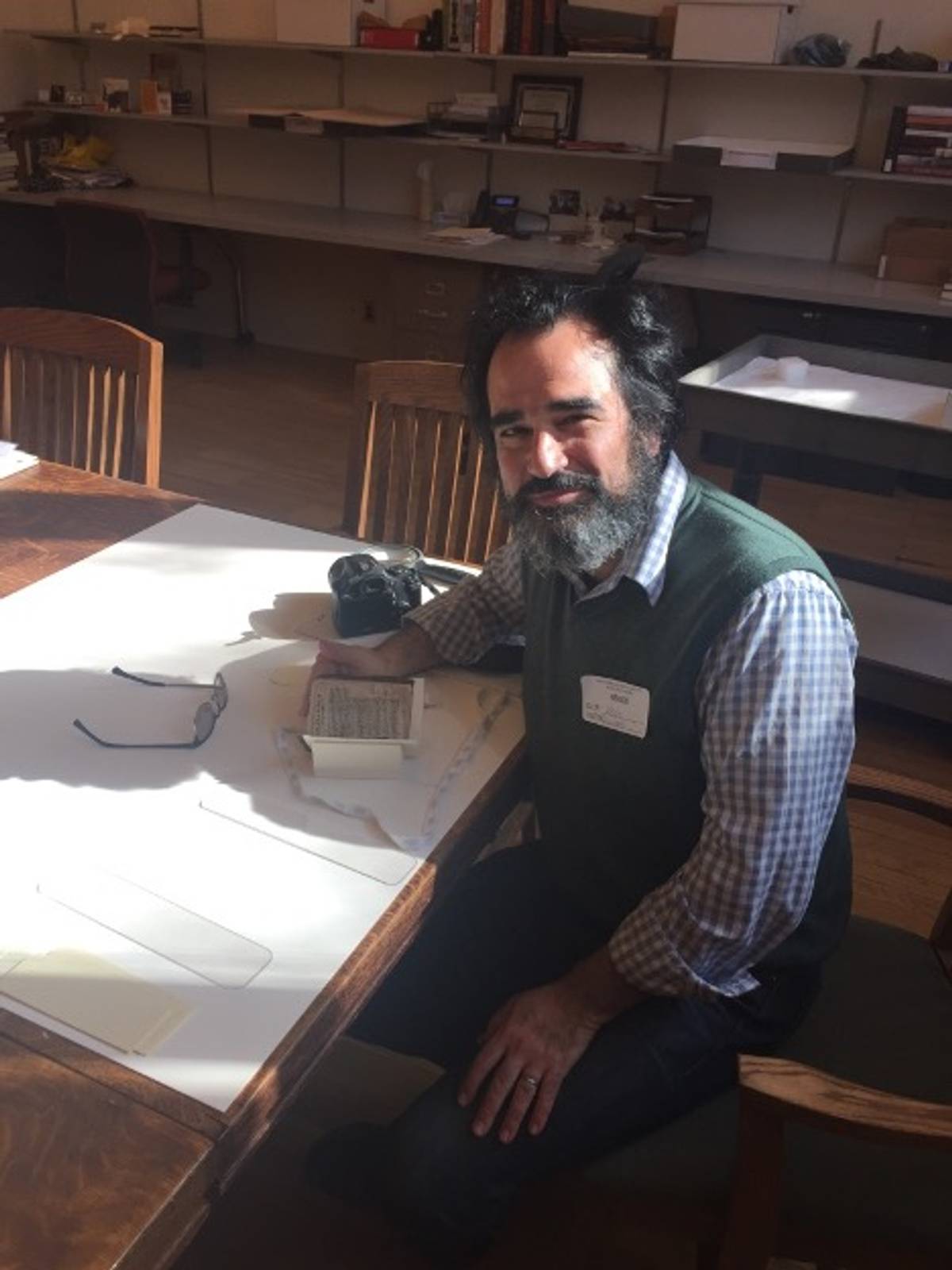

I myself am currently part of a team of scholars working to bring the full manuscript to a wider audience, both scholarly and popular. Along with my colleagues Ignacio Cuecas-Saldías and Jesús de Prado Plumed, we are in the process of producing an annotated transcription, English translation, and analytical study of the full manuscript of Carvajal’s religious anthology. The Carvajal anthology will hopefully be part of a larger project alongside my colleague Flora Cassen, Translating the Americas: Jewish Writings on the New World.

The manuscript was preserved along with hundreds of pages of testimonies and depositions related to the sprawling trial of the Carvajal family and their wider network of New World crypto-Jews. Along with the vast proceedings of the family’s trial, the anthology was stored in the Mexican National Archive (Archivo General e la Nación) along with other foundational texts of Mexican history. It remained there until its mysterious theft in 1932.

Scholars of the Mexican Inquisition and specifically those interested in this fascinating, complex case were only able to access the trial records and the transcription of the autobiography made by Alfonso Toro, the historian who wrote the first major work on the Carvajal family (link to Familia Carvajal). This was the case for pioneering scholars such as Seymour Liebman and Martin A. Cohen, as well as more recent scholars such as Miriam Bodian, Lúcia Costigan, David Gitlitz, and myself who explored the religious and intellectual life of Carvajal and the social and cultural world of the wider converso network in the Americas.

This was the reality until November 2016 when Leonard Milberg, a noted collector of Judaica and early Americana, sensed that a manuscript he was offered for purchase was the storied stolen Carvajal manuscript. After authenticating the manuscript and ascertaining that indeed this was the original stolen book, he alerted the Mexican authorities and the FBI. Milberg had two requests for the Mexicans: to be able to digitize the manuscript and to use it alongside his collection in a beautifully curated exhibition at the New York Historical Society. They agreed, and Princeton, Milberg’s alma mater, not only digitized the text but made it free and accessible to the wider world. The book is now housed at the Museum of Anthropology of Mexico City.

Now, for the first time in decades, we have access to Carvajal’s complete religious anthology. In addition to studying his actual words, the manuscript allows us to notice the unsaid. We can appreciate the gold leaf that he managed to get his hands on to illuminate the Ten Commandments and the way he ends his autobiography with some scribal flare. We can see the words he crossed out, the notes he added on the margins, and even appreciate the type of paper and ink he used.

I want to leave the reader with a few examples of Joseph Lumbroso’s religious creativity. From this point onwards I will refer to the author by the name he chose to use in his writings, Joseph Lumbroso. The translations are my own but they are informed by my conversations with my dear friends and collaborators Ignacio Chuecas and Jesús de Prado as well as the scholarship on the Carvajal family and the dynamics of crypto-Jewish experience. The original Spanish is based on Prof. Chuecas’s superb transcription.

Carvajal begins his autobiography with this biblical invocation:

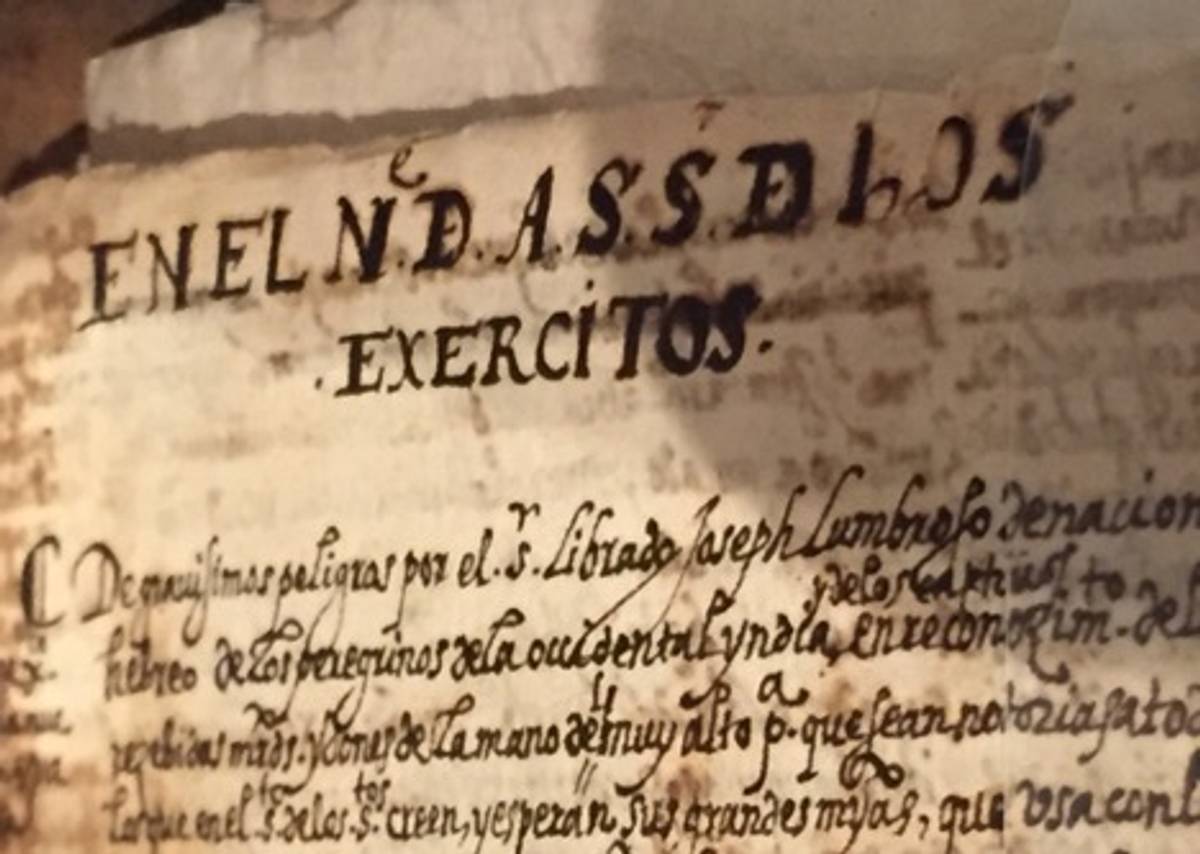

EN EL N.e .Đ. A. S. S.r Đ LOS

EXERCITOS

In the Name of Adonai Sabaoth Lord of Hosts

Lumbroso makes ample use of abbreviations and initials throughout his writing and this line is no exception. Adonai is one of the few Hebrew words that many conversos continue to use generations after their conversions. But could it be that Lumbroso knew of this Hebrew word for God from Christian sources?

As part of his penance after his first arrest and conviction for Judaizing, Lumbroso was placed under the careful eye of Fray Pedro de Oroz at the illustrious monastery of Santiago de Tlaltelolco on the outskirts of Mexico City. The monastery was the site of intense intellectual life in the early 16th century, when Bernardino de Sahagún and his teams of indigenous and Spanish scholars sought to record and analyze the scientific, historical, and religious knowledge of Mexico’s conquered indigenous peoples. While this activity was mostly completed before Lumbroso’s arrival, the monastery was still dedicated to instructing the children of the indigenous nobility in Christianity and the basics of European humanism. Lumbroso was tasked with teaching these students Latin, a language he mastered back in Spain when his parents sent him to a Jesuit school at Medina del Campo.

Paradoxically, Latin, the language of the church, was essential to Lumbroso’s crypto-Judaism. With Jewish books banned and the disappearance of any sort of official Jewish communal presence in the Iberian world, most conversos who wanted to follow the religion of their ancestors relied on oral traditions passed down from their parents or other members of their intimate crypto-Jewish circles. With Latin, however, intrepid readers could gain access to Catholic books with rich Jewish content. While vernacular Bibles were mostly outlawed in the Counter-Reformation Iberian world, someone like Lumbroso who was fluent in Latin could read the Old Testament and the Apocrypha in search of Jewish content. The Catholic breviary had a rich collection of Psalms in between the Pater Nosters and Ave Marias of the daily liturgy. Lumbroso describes gaining access to these texts as miraculous events, coming at pivotal moments of his religious journey and giving him access to the redemptive power of God’s word. At the monastery, he encountered more complex textual treasures. Works of biblical exegesis such as Oleastre’s commentary on the Pentateuch included long passages of rabbinic literature. Even when these passages were cited in order to prove the error of the Jewish approach, a subversive reading allowed a crypto-Jew such as Lumbroso to discover the words of the Talmudic rabbis and medieval philosophers.

In the Name of Adonai Sabaoth Lord of Hosts

“Lord of Hosts” has roots in the Hebrew prophets. Is that where Carvajal found this powerful Divine name? and is the “.S.” of that phrase Sabaoth or Señor? He might have subversively lifted this invocation from the Mass:

SANCTUS, Sanctus, Sanctus, Dominus Deus Sabaoth. Pleni sunt caeli et terra gloria tua.

While this line comes straight from Isaiah 5:3, its centrality in the Mass would have made this Hebrew word well known, not only to Carvajal but to his fellow conversos who did not read Latin with his level of mastery. Another possibility is that he encountered this phrase thanks to the small but significant numbers of Jews of the “lands of liberty” who crossed back into the Iberian world on personal business and who would share their knowledge of the siddur and mainstream Jewish practices with their converso brethren—someone like Ruy Díez Nieto, an Italian Jew of Portuguese converso origin who traveled to Mexico in hopes of improving his dire economic situation. Perhaps he taught Lumbroso some of the Hebrew words of the kedusha prayer, which is the highlight of the public service. In choosing this invocation, might Lumbroso be re-Judaizing the verse of the Latin mass?

Early in his narrative, Lumbroso describes the moment his family revealed their Jewish secret to him. It was:

un dia señalado que es el que llamamos de las perdonanças dia s.to y solemne entre noſotros a diez dias de la luna septima.

a special day that we call “of pardons”, a holy and solemn day for us, the tenth day of the seventh moon.

By maintaining the plural “de las perdonanças,” Carvajal follows the biblical and rabbinic usage of referring to the day as יומ הכפורים. This might point to an oral tradition that translated the Hebrew into Spanish, almost in the style of many Ladino translations. I see this as possibly having an oral Jewish source, as opposed to a salvaged Jewish source that Carvajal reformats from Christian texts.

These are just two examples in which the text of Lumbroso’s manuscript requires a translation of a translation. However, now I would like to turn to one page in that leather-bound journal that despite its simplicity, raises significant theoretical and practical questions. What follows is not a definitive treatment, but rather a reflection on the act of translation and what it can help us uncover about this text and the wider intellectual and social networks in which it exists. I will discuss the choices I made for rendering the text into contemporary English and what is lost in the process.

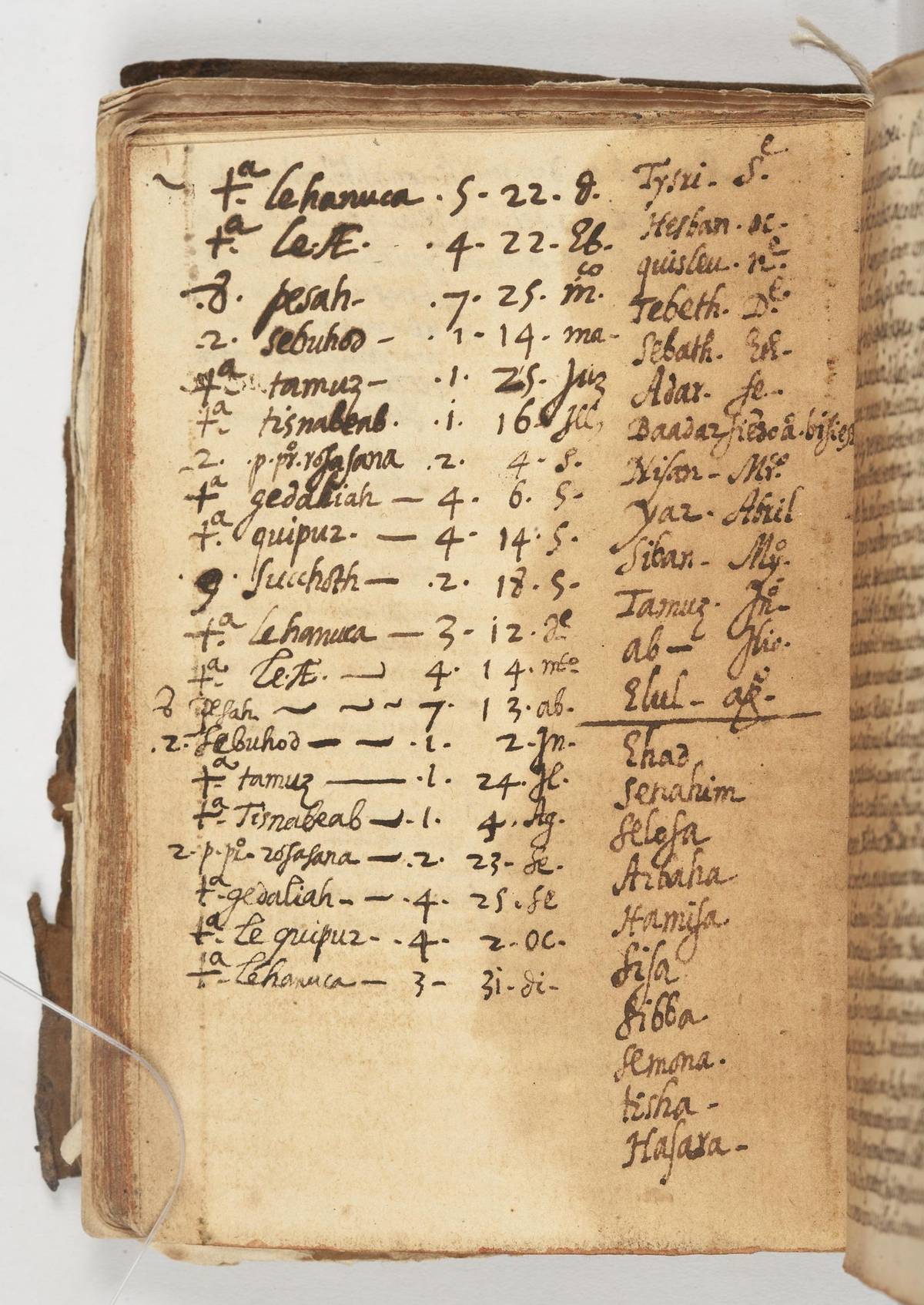

The reader first notices the columns, which are sectioned off to show the distinct categories of information they contain. The script is Latin, but the words belong to Hebrew, the forbidden language of the Jews. There are numbers as well, some in the “Arabic style”—1, 2, 3, 4—and others written out to phonetically match 1 to 10 in Hebrew, with the pronunciation of an Iberian Jew of the 16th century who probably spent some time in Italy. This page is a Jewish calendar listing the major Jewish holidays and the Christian date upon which they fall over two years. In another column, we find the name of the Hebrew months.

When approaching this text, one must consider a few questions—what might the source be? How did Carvajal access this information? Do the inquisitors refer to this calendar and does Luis shed any light on its composition or use? What might his form of transliteration of Hebrew tell us about his sources and his linguistic influences? In translating this text, how foreign and how accessible do I wish to render the original?

I first wanted the reader to see, and hear, the words recorded in Carvajal’s hand. I realized that this would be almost a direct transcription and not a translation. So I needed to let go of that fidelity and delight in the peculiarity of Carvajal’s calendar in order to produce something that was accessible and clear. I decided to translate the holidays and their dates into contemporary English to give the reader direct access to the text. I rendered Pesah as Passover because it is a common cognate in American usage. However, I rendered Succhoth as Sukkot and not as Tabernacles, and I did not translate Shabuhod as Pentecost or Feast of Weeks because these terms are arcane and don’t explain the Hebrew original in a way that would be useful to a contemporary English reader. If I kept Shabuhod or Tishnabeab I would preserve the particular orality of Carvajal’s calendar, the way that these words capture the way the Hebrew words were pronounced, especially with the strong Portuguese influence. But it would leave most readers confused.

Another intervention I decided upon was ignoring the notations written beside each holiday. What first seemed to me to be a “ta” (which seemed to stand for “Fiesta”) appears, according to my colleague Ignacio Cuecas to actually be a “+” or a “t” and an “a”. Most holidays have this annotation while others have numbers: 8 for Passover, 2 for Shavuot, 2 for Rosh Hashana, and 9 for Sukkot. Might this refer to the number of days of each holiday? Then why does Hanukkah go without this tag? I decided to leave this notation until I better understood its function. I also left out the Hebraic prefix “le” that Carvajal maintains before each holiday. I decided to “translate” the numbers listed which refer to the day of the week the holiday begins: 1 is Sunday, 7 is Saturday, 4 Wednesday, etc. By translating these numbers into their contextual meaning, the reader can understand the calendar, but they lose out on seeing how this particular 16th-century calendar might look. By having the original side by side, or at least accessible, we can offer the curious (and serious) both experiences.

There is a powerful act of resistance in this calendar, a rejection of hegemonic Catholicism; instead of saint days and Lent and Holy Week, we have a small list of holidays and their dates. But by inscribing the holidays with their transliterated forms, we can see how a converso living in the “lands of captivity” far from the centers of Jewish life in the “Old World” could strive to not only keep a Jewish holiday, but also say their names as other Jews do.

To refer back to an earlier example, in his autobiography Lumbroso refers to Yom Kippur as “de las perdonanças”—a fascinating Hebraicized translation in that he keeps the plural, which tracks with the commonly used plural form of yom hakippurim. But it is a translation. Here in transliterating the spoken Hebrew and Aramaic words Carvajal asserts his right to speak in a language that is forbidden and that he was cut off from. But at least in this circumscribed space of the calendar, he speaks Hebrew, allowing his fellow crypto-Jews who might also read this document to speak like the Jews who live in the lands of freedom.

Ronnie Perelis is the Chief Rabbi Dr. Isaac Abraham and Jelena (Rachel) Alcalay Associate Professor of Sephardic Studies at the Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies of Yeshiva University.