The Cold Civil War

Is freedom our right or our privilege?

By now all of us have had the experience of arguing with a human brick wall over some question related to the pandemic. It doesn’t matter what side of the debate you’re on. You can be the founder of your local Dr. Fauci fan club, or you can be Robert Malone himself: intransigence over vaxxing, masking, distancing, mandates and school closures is endemic across the political spectrum. We’re beyond the point of persuading other people on the basis of logic and evidence. That’s not what our fights are about anymore.

A map of America these days is not a map of who “follows the science” and who “denies” it. It’s not a map of penchants toward conspiracy theories. It’s not a map of altruists versus egotists. It is a map of how Americans regard authority.

I recently read David Hackett Fischer’s cultural history of colonial America, Albion’s Seed. In the conclusion to that book, written in 1989, Fischer notes that federal census data have consistently shown the various geographical regions of the United States to have even more cultural differences between them than do the myriad nations of Europe.

Fischer’s thesis is that American social and political history has been shaped fundamentally by the disparate ancient cultures of the populations of four geographical regions of England, which were the respective sources of four waves of migration to the American colonies. The first was the Puritan East Anglians who settled Massachusetts. The second was the Royalist cavaliers from the south and west of England who emigrated to Virginia. The third was the Quakers of the English Midlands who colonized Pennsylvania and the Delaware Valley. And the last was the anarchic warrior clans of the north counties of England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland who made their new homes in the mountainous backcountry of the Appalachian South.

By the 20th century those four cultures had expanded across the continent. The Puritans dispersed westward, across a northern belt of the present United States, settling upstate New York, the upper Midwest, the northern Plains and the Pacific Northwest. The Quakers and their descendants fanned out from Pennsylvania to the Ohio Valley, and farther to the Rocky Mountains. The cavaliers of Virginia spread into the Deep South and west into Texas, mixing there with the progeny of the backcountry Appalachian colonists, who had moved west into the Ozarks, Texas, and Oklahoma, and then to Southern California as Okies in the Dust Bowl.

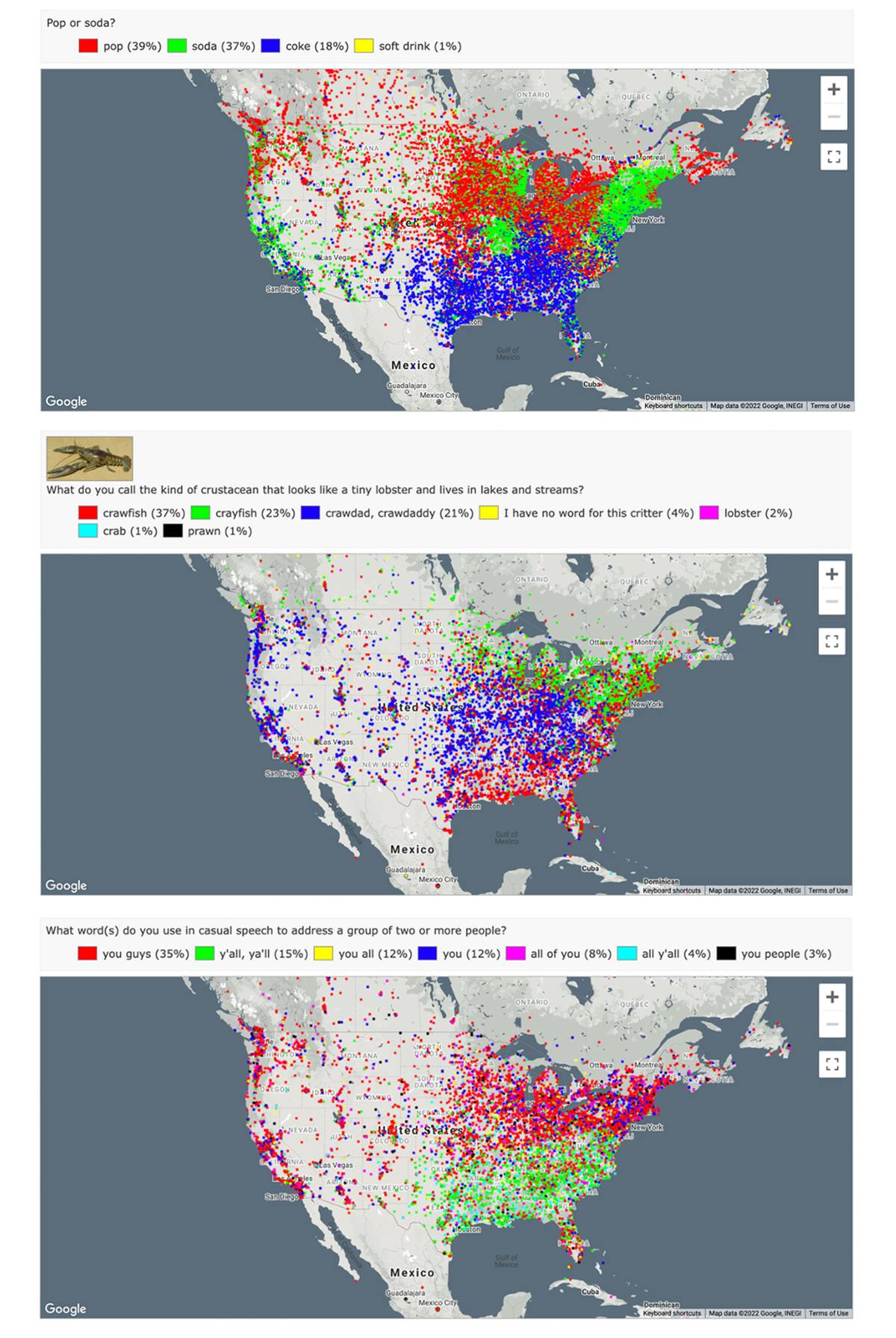

The continuing influence of these divisions can be roughly discerned by poking around at the visual results from the famous New York Times’ dialect quiz.

A couple of obvious things stand out across most of these data visualization maps. First, there’s an unmistakable division between the northern and the southern sections of the eastern United States. Second, the West Coast shares the lexicon of the Northeast and the mid-Atlantic much more than it does that of the Southeast.

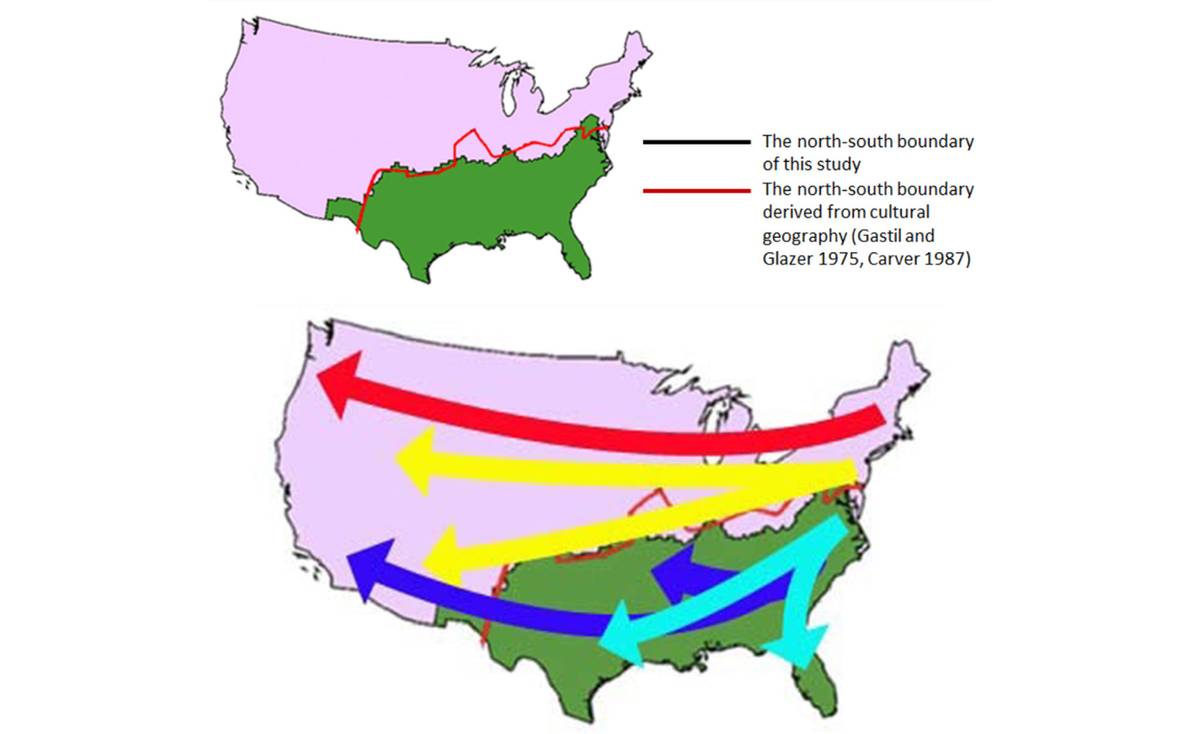

Fischer includes his own map, from a study in the 1960s, of regional speech patterns in the U.S. that show roughly the same thing (my own color coding added; the green and blue areas are hybrid populations—Midland/Northern for blue, and Highland Southern/Midland for green).

To make it starker still, here’s a map from a 2016 study on a year’s worth of geotagged tweets, comparing lexicons regionally.

The distinct British ethnocultural groups that settled America carried with them ancient cultures—what Fischer calls “folkways”—that were startlingly different from one another. From the ways they built their dwellings to the ways they cooked their food to the ways they named their children, each of the four groups had distinctive customs, values, and manners that endured through generations and across thousands of miles of westward expansion.

Perhaps the most consequential of those differences were their political philosophies. Fischer describes those of all four in detail, but to me, two of them are particularly relevant to our current day: that of the New England Puritans, and that of the Appalachian Scotch-Irish.

The New England Puritans believed in what Fischer called “ordered liberty.” Ordered liberty was the notion—intuitive to many of today’s American liberals and conservatives alike—that while individuals have rights, it’s necessary for the state to put limits on them to preserve the social order. Gun control is a straightforward example: Individuals may have the right to bear arms (for the purposes of sport and self-defense, for instance), but if there were no limits on that right, so the thinking goes, America would turn into a bloodbath. To protect our right to go about our lives without getting shot, we forfeit some of our individual rights to the state, which is granted the power to regulate us for our own good (permits, background checks, wait periods, red flag laws, bans on certain kinds of guns, etc.). The same logic holds universally, whether the issue is environmental protection, public safety, drug use, speed limits, labor laws, or whatever.

“Forfeit some of our individual rights to the state” might actually be understating the case. Legally speaking, the principle that encapsulated the Puritans’ view was that of “prior restraint”—that is, the notion that the individual doesn’t have a “right” to much of anything until it’s granted to them by the commonwealth, like a driver’s license or a fishing permit. The Puritan colonists took this idea to a weird degree. The Massachusetts town of Eastham, for example, required that a bachelor must kill six blackbirds or three crows before being permitted to marry.

The political philosophy of the Scotch-Irish colonists of the Appalachian backcountry was the inverse of that of the Puritans. The settlers of this region came from the northern counties of England, the lowlands of Scotland and the north of Ireland. This region, along the border of two kingdoms, had been ungovernable for centuries. The monarchs of neither England nor Scotland could tame its fierce, unruly and pugnacious inhabitants. In the mid-16th century, the parliaments of both countries passed a decree that held that “All Englishmen and Scottishmen are and shall be free to rob, burn, spoil, slay, murder and destroy, all and every such person and persons, their bodies, property, goods and livestock … without any redress to be made for same.”

Nearly every bit of the region’s culture, from how they constructed their cottages to the sports they played, were rooted in this history of perpetual warfare and arbitrary violence. Their political philosophy was no exception. The Scotch-Irish were militantly committed to their unconditional independence and autonomy. Unlike the Puritans, they did not view their individual rights and freedoms as privileges granted them by the state. Far from the bestower of rights, to the Scotch-Irish, governments were an invading, oppressive force, that could only encroach on one’s freedom, not give it. One’s entitlement to be left alone, to do what one wished with one’s family, property and land, was a natural right, which the Scotch-Irish were prepared to fight and die for. The colonists from this warring border region brought these convictions with them to the Appalachian backcountry, and, in time, west to Missouri and Texas and Oklahoma and all the way to Southern California, which, it should be recalled, was the birthplace of the Reagan revolution.

Today, the United States is a patchwork tapestry of these fundamentally incompatible political world views. In some regions, they’ve fused in unexpected ways, such as in Northern California, where a traditional New England penchant for moralistic government has been merged with a countercultural version of Appalachian anti-authoritarianism in a unique and, some might say, uniquely dysfunctional ideology that Michael Shellenberger calls “left libertarianism.” But in most places they exist, from one county to the next, in entirely separate proximity from one another, like neighbors who only talk to each other when they’re fighting over the property line.

Here’s a map from the Institute of Health Metrics at the University of Washington, based on data on vaccine hesitancy from Carnegie Mellon University and Facebook.

It’s not quite as clean as the earlier maps, but there’s still an unmistakable tilt in favor of vaccines in the Northeast, the West Coast, most of the desert Southwest and the upper Great Plains, and a more modest tilt against them in the Southeast and the central Plains, with a mixed picture in the Great Basin, the Great Lakes and the mountain West. Again we see the Northeast and mid-Atlantic breaking in a markedly different direction than the Southeast, and the West Coast aligned largely with the former.

The late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen some significant geographical realignments, such as Yankees populating the South, Californians spreading throughout the Sunbelt, and Mexican and Central American immigrants settling into cities and towns throughout the continental U.S. These migrations and others like them have complicated and enriched the politics of nearly every region, but the broad contours of the cultural zones established by the diaspora of Fischer’s four British colonial populations remain discernible. We have a Northeast, a West Coast and an upper Midwest falling into easy compliance with the new rules, and an Appalachian and coastal South staunchly resisting them.

On the one hand, we have an America whose political philosophy traces back to the ordered liberty of New England, where the unbridled freedom of individuals, with their inherent corruption and recklessness, was regarded as a threat to the collective order, and where our personal well-being was safeguarded only by imposing rules from above. Democratic procedures existed to ensure that those rules reflected the public’s will and best interests, rather than the parochial interests of the rule-makers. But at the end of the day, we needed the Leviathan to protect ourselves from each other.

On the other hand, we have an America that regards individual freedom as an a priori condition inherent to our moral existence as human beings, and the concentrated power of government as an ever-present threat to that freedom. This is the political philosophy that originated in the violent, lawless region of the north British borderlands, where people’s vantage point of the state was from the opposite end of a saber.

I live in California, in the most liberal metropolis in the country. Almost everyone I interact with largely subscribes to the New England philosophy of ordered liberty. If we don’t force people to get vaccinated, I’m told, we’ll be forever imprisoned by the most selfish among us who insist on their precious “freedoms” even when it costs people their lives. It’s a perspective redolent of the Puritans who declared in the Westminster Confession of 1647 that “Man, by his fall into a state of sin, hath wholly lost all ability of will to any spiritual good accompanying salvation.” Apart from the very few whom God favored, man was “wicked and ungodly,” hopelessly controlled by “the power of Satan,” and ultimately hell-bound. Clearly, such creatures could never be left to their own devices; they could be protected from their own base temptations and appetites only by placing strict limits on their freedoms.

Then I go online and hear a radically different perspective. Masking and distancing rules, lockdowns and vaccine mandates, I’m told, have about as much to do with protecting us from COVID as secret mass digital surveillance had to do with protecting us from terrorists. Day by day, we’re ceding the liberties we take for granted to nameless government officials and technocrats who are accountable not to us and our families but to politicians, corporations, and oligarchs. A new disciplinary and surveillance regime is being erected all around us, and we’re headed toward a future under a creepy corporate biosecurity state run by tech and Big Pharma, with Chinese-style social credit systems and endless mandatory injection protocols. This is a worldview that has survived its passage from the English-Scottish borderlands and the Appalachian backcountry to wide swaths of today’s United States more or less wholly intact. Its reflexive distrust of the CDC, the NIH and the political and corporate establishments is not just comparable to the ancient north British antipathy for the avowed authority of the crown; it’s literally the same thing.

The argument between these two sides is not about facts and data and experts and science. It’s not even an argument about appropriate public policy. In fact it’s not an argument at all. It’s a head-to-head collision between two vastly different conceptions of what a free society should look like.

There’s nothing new about this conflict—these two fundamentally incompatible political philosophies have coexisted in America for centuries, and in England before it. But in this new era of endless global emergency, the omnipresence of social media, and the reach of digitally empowered state actors, coexistence has become increasingly impractical. The pandemic forced us into a circumstance in which America’s public health response was split between two diametrically opposed policies, each vying to prevail over the other, each side regarding the cost of defeat as existential. Today, mask mandates or other pandemic-related measures are at long last being rolled back, but the war to define America’s relationship to freedom and authority is just getting started.

Leighton Akira Woodhouse is a freelance reporter and documentary filmmaker. He writes at leightonwoodhouse.substack.com.