Gemoro Loshn: The Lullaby of Jewland

The rhythms of Talmudic study are the truest form of Jewish music

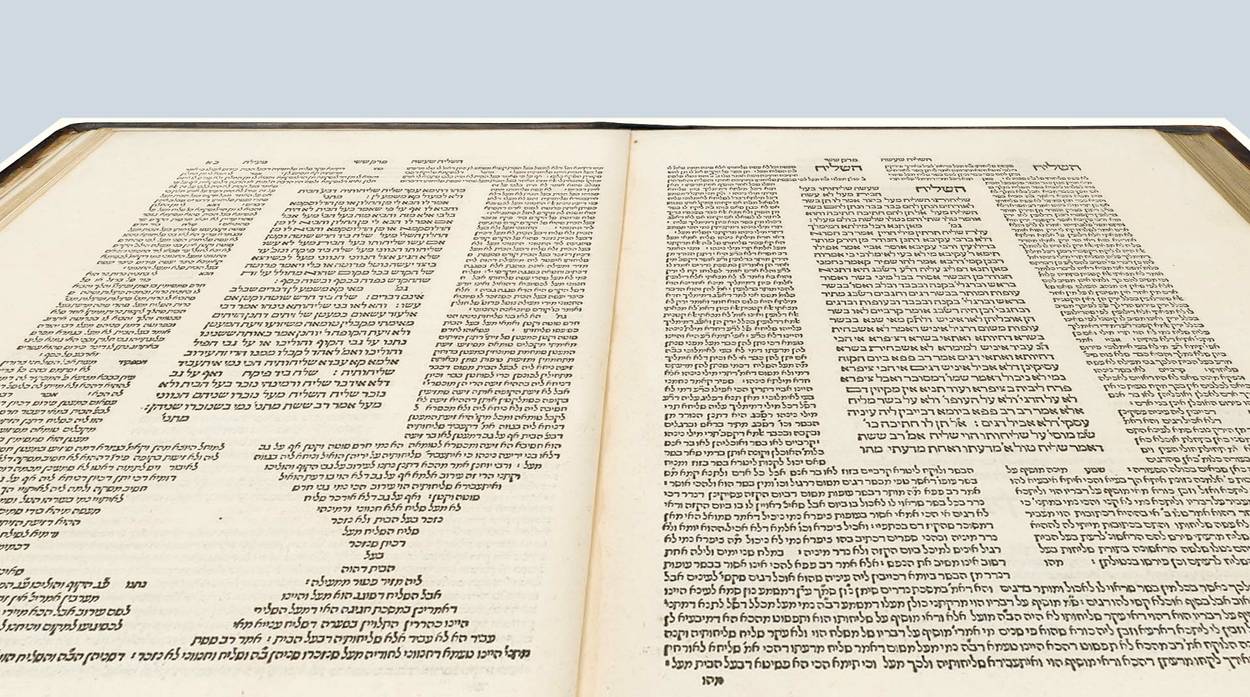

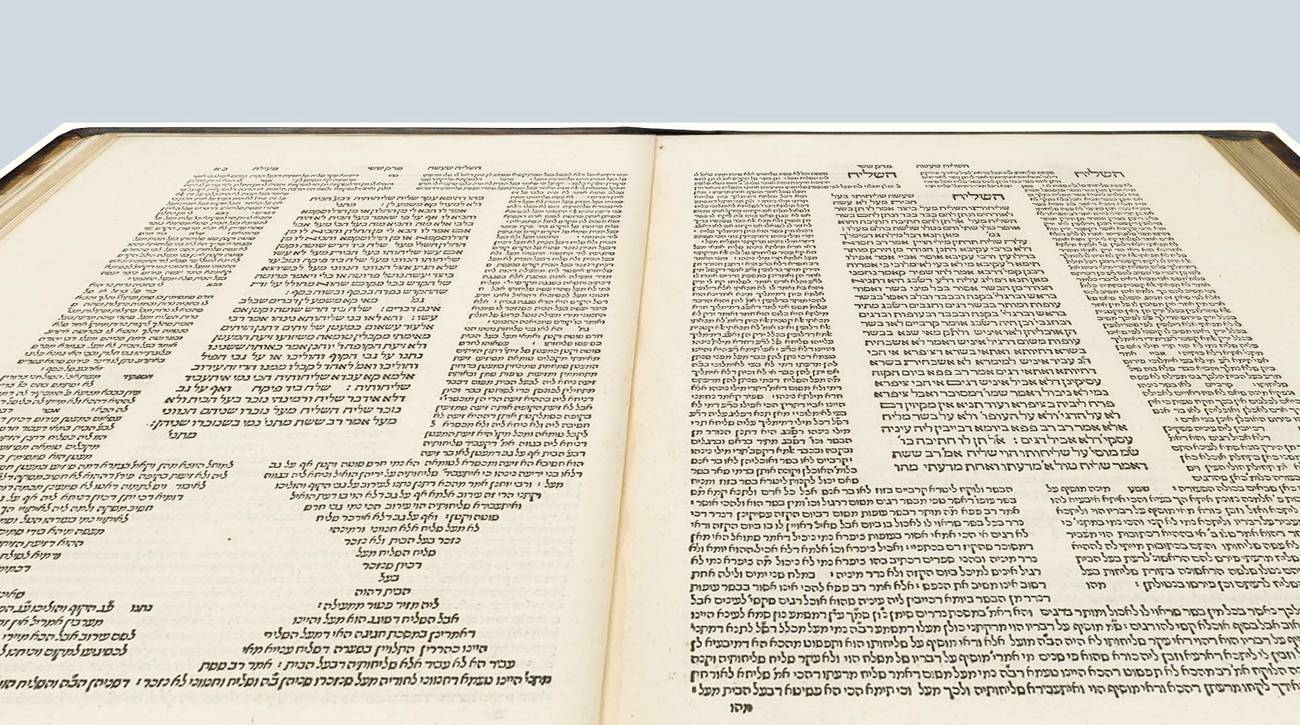

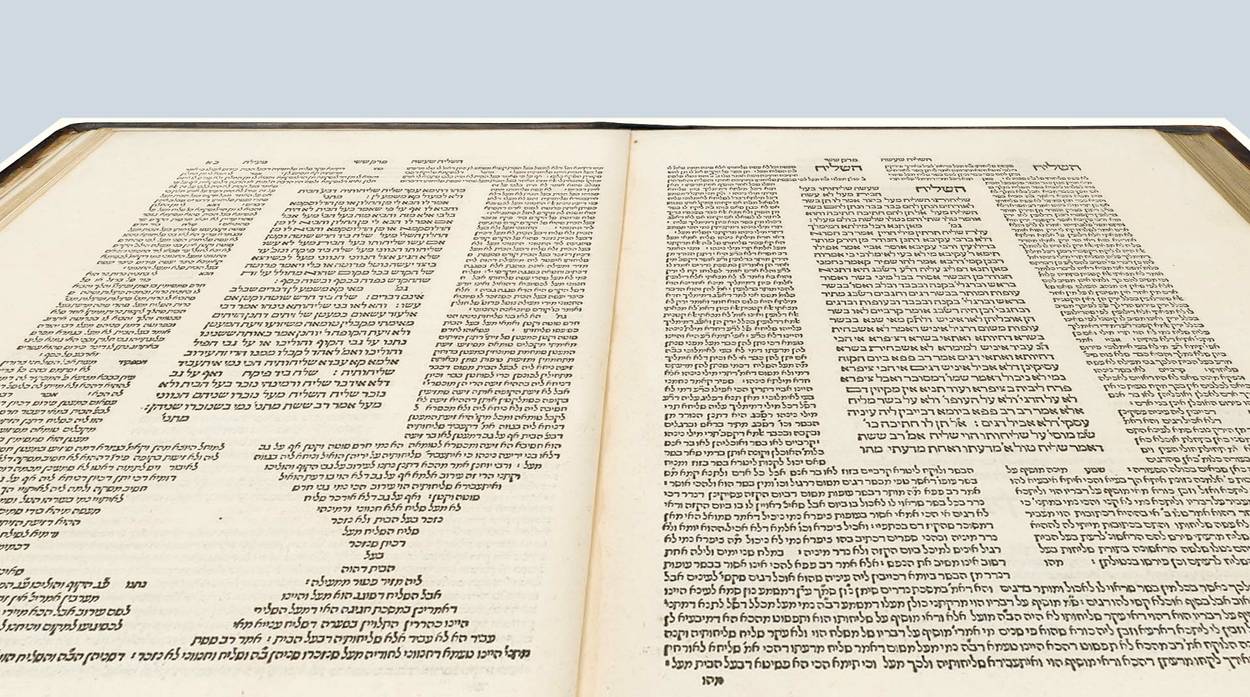

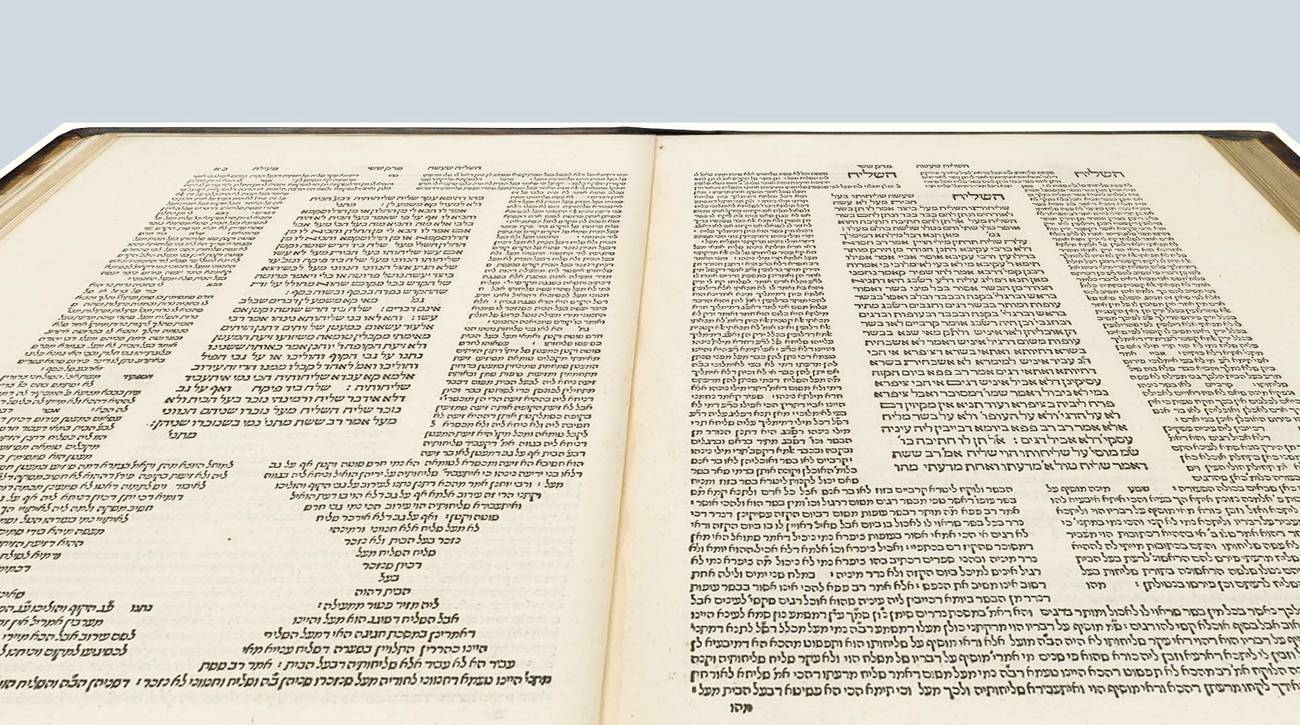

Talmudic study—its melodies, rhythms, and counterpoints—has been the music of Jewish existence, providing the background tunes for even the most everyday of Jewish lives: It is the lullaby of Jewland. It is frequently literally musical, or even musicological. The study of Talmud provides a kind of soundscape, the music of Jewish life. In making this statement, I am, as have others, shifting from thinking of the Talmud primarily as text to an oral and aural practice in and for itself.

As Zelda Kahan Newman has shown, the intonation patterns of the Talmud are what make Yiddish sound “Jewish.” These particular patterns of intonation and the way they semantically match patterns in Yiddish were discovered—as noted by Newman—by Uriel Weinreich, and they are in no way “elitist” in Yiddish. Newman also documents the fact that, according to Rav Kafih, intellectual leader of the Yemenite Jews in Israel, these patterns are found widely in the daily speech (in Judeo-Arabic) of his folk, too. In other words, and this is highly significant, this nearly melodic speech pattern is by no means endemic only to Ashkenazic Jews or Yiddish speakers, but seemingly produced by the melodies and rhythms of Talmudic study.

The study of Talmud could constitute the Jewish diaspora both in antiquity and today because it provided a common language. Jews have always had a separate language, or more precisely a set of separate languages, that marked them off as a nation alongside or even within other nations. Once there was Yiddish for the large majority of the world’s Jews, and Judezmo, Judeo-Arabic (in all its varieties), Judeo-Persian, Judeo-neo-Aramaic, Judeo-Tajik (and others) for the rest. Now, most of these are gone from the world, or nearly so. I am persuaded that it is a differentiated language, the very fact of it, that contributed mightily to the continued existence of the nation as such, and was critical in the formation of diaspora in the sense in which I use it. Two questions arise, then. The first is how did such a linguistic diversity constitute—or better, contribute to constituting— all Jews as a single collective? And second, how can we imagine this in a world in which many—perhaps most—Jews no longer share a Jewish language, unless that language is Hebrew.

When I was a child, my parents spoke a language they called “Jewish”—translating the word “Yiddish” into English—when they didn’t want children to understand. I once asked them if a certain person who worked for them spoke “Christian”; they didn’t understand the question. The closest thing to “Christian” as a language is the Jewish name for Latin, galakhes (tonsure talk or monkish). But Jews everywhere have had their own forms of speech. Famously, one of the reasons that the Israelites were redeemed from Egypt, according to the Midrash Leviticus Rabbah, is that they did not change their language. It was the fact of continued speech in יהודית or עברית that enabled the collective to be preserved for the centuries, in order that it would maintain a distinct identity upon being afforded the opportunity to leave Egypt. The 18th-century leader (perhaps inventor) of what is inaptly called today “ultra-Orthodox” Judaism, the Hatam Sofer, realized that the best guarantor of continued Judaic existence was continued speech in the Jewish language; in his view, of course, that was Yiddish. On the other side of Jewish modernity, Leon Trotsky (Lev Davidovich Bronstein) wrote, “On the other hand, the Jews of different countries have created their press and developed the Yiddish language as an instrument adapted to modern culture. One must therefore reckon with the fact that the Jewish nation will maintain itself for an entire epoch to come.” He didn’t reckon with the Nazis.

Obviously these Israelites also must have spoken the language of Egypt—if only to receive their marching orders. (And what did Moses speak with his adoptive mother and her father? Or Joseph at the court?) The net result is the sort of diglossia typical of Jewish historical existence everywhere, devotion to a fluent, rich, complete transnational Jewish language (Yiddishkayt/Judezmo), together with facility and participation in the language of the place “where I live” (doikayt). Within the diaspora context, it is the sharing of the Jewish tongue that provides the glue binding the dispersed, transnational nation into a collective, not simplex but duplex, at the least.

We can see (following Max Weinreich) that what conjoins all of the Judeo languages is not the component that joins them to the languages of the locale in which they have come into being (Central Europe for Yiddish, and so on), but the component that is drawn from the shared language of the Jews, namely the language of the Babylonian Talmud, already a rich amalgam of Hebrew and Aramaic. It is this component of Yiddish (and, I warrant, all other Jewish languages) that provides the vehicle for the cultural nexus that we name the Jewish nation. In a profound sense, it is these/this Jewish language(s) that produce the shared soundscape of the world Jewish diaspora—the deep structure for my seemingly ungrammatical question, “What is the Jews?” It is the shared components of these languages with the languages of the people that Jews live among that constitute them as diasporic, an irreducible component that is shared with the local population as well: diaspora loshn.

From Talmud to Folk Song: Mai ko mashme-lon

Consider a famous Yiddish art song that became, among other things, a Yiddish folk song, as well. It’s by Avrom Reyzen. I first heard this song when I was about 8 or 9 years old. I am giving here only one stanza in Yiddish transliteration and in my first stab at English to illustrate my point.

May ko mashme-lon der regn?

Vos zhe lozt er mir tsu hern?

Zayne tropns oyf di shoybn

kayklen zikh vi tribe trern.

Un di shtivl iz tserisn,

Un es vert in gas a blote;

Bald vet oykh der vinter kumen —

Kh’hob keyn vareme kapote. . .

What does the rain mean?

What does it teach me?

Its drops roll down the windowpane

like sad tears.

And my boots are torn,

and there’s mud in the street.

Soon the winter will be here,

and I don’t have a warm coat.

I now want to talk the poem into English before giving an amended translation toward the end of this reading. The first and key phrase that generates the whole poem is May ko mashme-lon, which is drawn directly from the Aramaic of the Talmud, Gemoro loshn, where it literally means: “What does this teach us?” It is evoked when a given sentence quoted in the Talmud seems not to add anything to our knowledge, either because we know what it says already or because what it says seems trivial, a mere historical datum, a fact of no significance. Reyzen follows the Aramaic with a literal translation into Yiddish using the precise Yiddish idiom which is, itself, a direct translation from the original Aramaic Talmudic phrase: Mai ko mashma lon, which means literally “what does it make us hear,” but idiomatically “what does it teach us?” Just like the Yiddish idiom that it gives rise to: What does it let us hear; what does it teach us?

The answer to this question in the Talmud always discovers some normative reason for the statement having been made. Let us see now, then, a real example of this from the Talmud itself:

Abaye said to Rav Dimi, and some say it was to Rav Avya, and some say Rav Yosef said to Rav Dimi, and some say it was to Rav Avya, and some say Abaye said to Rav Yosef: What is the reason for the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer who said: These weapons are ornaments for him? As it is written: “Gird your sword upon your thigh, mighty one, your glory and your splendor” (Psalms 45:4), indicating that a sword is considered an ornament.

The Gemara relates that sometime later:

Rav Kahana said to Mar, son of Rav Huna: Is that really a proof? This verse is written in reference to matters of Torah and should be interpreted as a metaphor. He said to him: Nevertheless, a verse does not depart from its literal meaning.

Rav Kahana said that one cannot adduce the verse as evidence for the Halachic status of personal weaponry, since the verse itself is an allegory for Torah. There are no literal weapons described here at all from which to learn Halacha. But Rav Huna returns to Rav Kahana that we have a principle of hermeneutics that whatever the metaphorical or allegorical meaning of a verse, its literal meaning must also function as well. Then:

Rav Kahana said about this: When I was eighteen years old, I had already learned the entire Talmud, and yet I did not know that a verse does not depart from its literal meaning until now. The Gemara asks: Mai komashma lon? [What is Rav Kahana teaching us with that [simple autobiographical] statement?] The Gemara answers: [He comes to teach that a person should first learn and then interpret.][Shabbat 63a]

Mai kamashma lon, as we see is a very technical term in the so-called “elite” discipline of Talmudic study, but it escapes from that milieu into the world, from the world of lernen to the world of everyday human life in the present, and hardly of only an elite.

In the Yiddish poem, this common Talmudic phrase isn’t talking about a passage from the Mishna or a statement of the great Rav Kahana; it’s talking about rain and the misery it brings to the poor Yeshiva bokher. The phrase itself, as it were, breaks out from the House of Study and moves out into the street, a perfect figure for the way that Talmudic lingo functions in the generation of a whole—nonelite—culture. From the book to the mud! The thematization of the move from scholastic elite to the world of all Jewish life is matched by the enactment of it in the very migration of the phrase from one Sitz im Leben to another, from the Talmudic page to the suffering of poor Jews and the passionate interrogation “What does it teach us?” Just as any statement in the Talmud must teach us something significant, so also the miserable rain must teach us something. Without recognition of the Talmudic phrase—even if one has never actually learned a page of Talmud—the song is unintelligible, so the song functions also as a mode of education for the masses. Jewish language functions somehow analogously to the illuminated windows of the great cathedrals in bringing the Talmudic culture to Everyjew.

This is how the first verse of the song would read correctly translated into English:

Mai ko mashma lon the rain?

What does it teach us?

Its drops roll down the windowpane like sad tears.

And my boots are torn

and there’s mud in the street.

Soon the winter will be here,

and I have not a warm coat.

This is a thematized representation of how Gemoro loshn comes into the vernacular. The phrase is so pervasive in the mind of the Talmud students that it, and a version of the thought carried with it, goes out into the world and into Yiddish and articulates his misery. What does this misery mean? What is it teaching us? Mai ko mashma lon? Rain and cold have become a text to be read, to be interpreted, but absolutely retain their miserable concrete reality.

The last verse of the song is in my mind the most poignant of all:

May ko mashme-lon mayn lebn?

Vos zhe lozt es mir tsu hern?

Foyln, velkn in der yugnt,

Far der tsayt fareltert vern.

Esn teg un shlingen trern,

Shlofn oyf dem foist, dem hartn,

Teytn do di oylem haze —Un oyf oylem habe vartn..

Mai ko mashma lon my life?

What does it teach us?

Our youth is rotten and withered

And we become old before our time

We eat at others’ tables and wash it down with tears

My fist is my pillow

We slay here This World

And await only the Next.

The lament of the Yeshiva bokher turns finally into a cry of protest at his lot. The answer to the question: what does it teach us, what does it give us to understand is finally given: nothing! The youths spend their lives in the dark House of Study, growing old before their time without any of the pleasures of “this world”; certainly not food as they eat only the poor food that they are given. Eating “days” [Teg in Yiddish] was the custom by which the Jewish villages supported the yeshiva boys: Monday, I eat by Goldwasser; Tuesday by the Hazan’s house, etc. No wine, maybe no water even to drink; the poor food is washed down with tears. Gefilte Fisch and Moscat only in the next world. It is important to claim and to underline the claim that this poem/song is not parodic, nor a “secular” attack on the tradition of study, but a cri de coeur voiced from within. As such, its blended language, manifesting the voice of bitter grievance from within the very idiom and melody of that which is being grieved against, makes it powerful, a cry of pain without contempt, but also a stand against nostalgia and romanticization.

It is the recognition of that phrase, that formulaic question, as Talmudic that is key to perceiving the power of the poem. Although there is still much that could be said in a proper slow reading of Reyzen’s poem, one thing that must be mentioned here is that the melody with which the poem has been supplied and in which it is sung evokes powerfully the melody of Talmud study itself. This is an excellent example in literary form for what Sarah Bunin Benor calls with reference to various Jewish languages the “transfer of Hebrew and Aramaic loanwords from rabbinic texts to the study of those texts and then to everyday speech. ”Once again, the match between the thematization and the enactment of this linguistic element is a near-perfect fit, because by entering the world of the art song, which is for Yiddish a direct track to folk song, the move of the phrase into the vernacular is not only described, but performed. It is the sum total of such performances that, to my mind, constructs the language—in this case, Yiddish—as a Jewish language and thus a vehicle of diaspora. It “works” as well in English, but for a much more limited segment of the population; in English, it will make sense only among those for whom the Talmudic phrase is (still) a household word, for speakers of Yeshivish or Frumspeak (whether frum or not). To keep Jewish alive, we need many, many more such households.

The correct transliteration of the song has been adapted from a publication of the Hebrew Publishing Company, New York, 1915. I have only substituted the word “foist” (fist) for the word “bank” (bench) as the former appears in most versions of the song as published. The translation is mine. The text can be examined here. I wish especially to thank my colleague professor Chana Kronfeld for her help with the Yiddish. I am also grateful to Dr. Dine Matut and professor Yitzhaq Niborsky for their help with these materials.

Daniel Boyarin is the Caroline Zelaznik Gruss and Joseph S. Gruss Visiting Professor in Talmudic Civil Law at Harvard Law School.