The Real History of the Mennonites and the Holocaust

The story of war refugee Heinrich Hamm’s anti-Semitic and anti-Bolshevik involvement with Nazism betrays the Christian denomination’s upstanding reputation for humanitarianism

A great gulf looms between the image of Mennonites as a peaceful Christian denomination engaged in humanitarianism and peace building around the world, including in the Middle East, and what historians have begun to reveal about the entanglement of a substantial minority of Mennonites with National Socialism during the 1930s and ’40s. So, who hid the Mennonite involvement with Nazism and how?

After World War II, the primary narrative that Mennonite leaders in Europe and North America crafted about their churches’ activities in the Third Reich emphasized repression and hardship. The denomination’s leading aid organization, Mennonite Central Committee (MCC), worked during the late 1940s and early 1950s to help resettle thousands of European Mennonites who were displaced as a result of the war. MCC relied on financial and legal assistance from larger refugee agencies affiliated with the United Nations. In dealing with their United Nations colleagues, MCC officials insisted most of their wards “were brutally treated by the German occupation authorities” and “did not receive favored treatment.”

One of Mennonite Central Committee’s star witnesses was a refugee named Heinrich Hamm. Like tens of thousands of other Mennonites who had experienced the Nazi occupation of Eastern Europe, Hamm was from Soviet Ukraine, and had retreated westward with German troops in 1943 to avoid again coming under communist rule. Five years later, Hamm was an MCC employee, helping to run a large refugee camp in occupied Germany. MCC’s special commissioner in Europe passed to United Nations officials Hamm’s story of evacuating from Ukraine to more western areas:

It is quite an erroneous idea to think that all Mennonites were brought to Poland to be settled on farms. I and my family came to a camp Preussisch-Stargard in the Danzig area. Immediately representatives of various works and concerns came to fetch cheap labour. I had to work in a machine factory where I remained until the end of the war. Besides the four Mennonite families many Ukrainians, Frenchmen and Poles worked there also. There was no difference in the way these various national groups were treated.

The efforts after the war by Mennonite Central Committee to portray refugees like Heinrich Hamm as victims of Nazism were largely successful. Based on statements from MCC officers and many migrants themselves, refugee agents affiliated with the United Nations believed that “the majority of those [Mennonites] who found themselves in Germany at the end of the war had not come voluntarily to that country. They were deported alongside other Russians to be used as slave labourers.” As another evaluation concluded, Mennonites were fundamentally “an un-Nazi and un-nationalistic group.” MCC ultimately succeeded in relocating most of the refugees under its care with United Nations assistance to new homes in West Germany or overseas, mostly in Canada and Paraguay.

Hamm and his colleagues at Mennonite Central Committee wanted United Nations-affiliated refugee organizations and other interested parties to think that any collaboration by members of the denomination with National Socialism was exceptional and insignificant. They implied that if some young men had perhaps gotten carried away, surely this was because they had been drawn away from their faith under Soviet rule. But wartime records do not corroborate this story.

Hamm was a leader at the heart of Mennonite institutional life in Europe both during and after WWII. There is no question that he and tens thousands of other Mennonites experienced atrocities in the Soviet Union, and that this history of suffering conditioned their positive reception of National Socialism. Indeed, Hamm’s wartime writings show that he considered his support for the most heinous crimes of Hitler’s state to be directly related to his own efforts to aid fellow Mennonites. Hamm saw Jews and Bolshevism as being part of a single evil cabal that threatened his ethnic and faith communities, and he welcomed Nazi efforts to redistribute Jewish plunder.

Who hid the Mennonite involvement with Nazism and how?

Understanding Hamm’s wartime activities also helps to clarify the significance of Mennonite Central Committee’s European refugee operations. Were we to consider only MCC’s postwar reports to bodies like the United Nations, we might assume that the denomination’s premier aid organization was acting in good faith—that leaders were unaware of the Nazi collaboration of refugees like Hamm. But this reading cannot be supported. In a very literal sense, Hamm was MCC, a paid employee and spokesperson. And that was precisely the point. The purpose of MCC’s refugee program was to assist people facing legal or material hardships because of their associations with Nazism. Employing wartime leaders like Hamm provided valuable expertise.

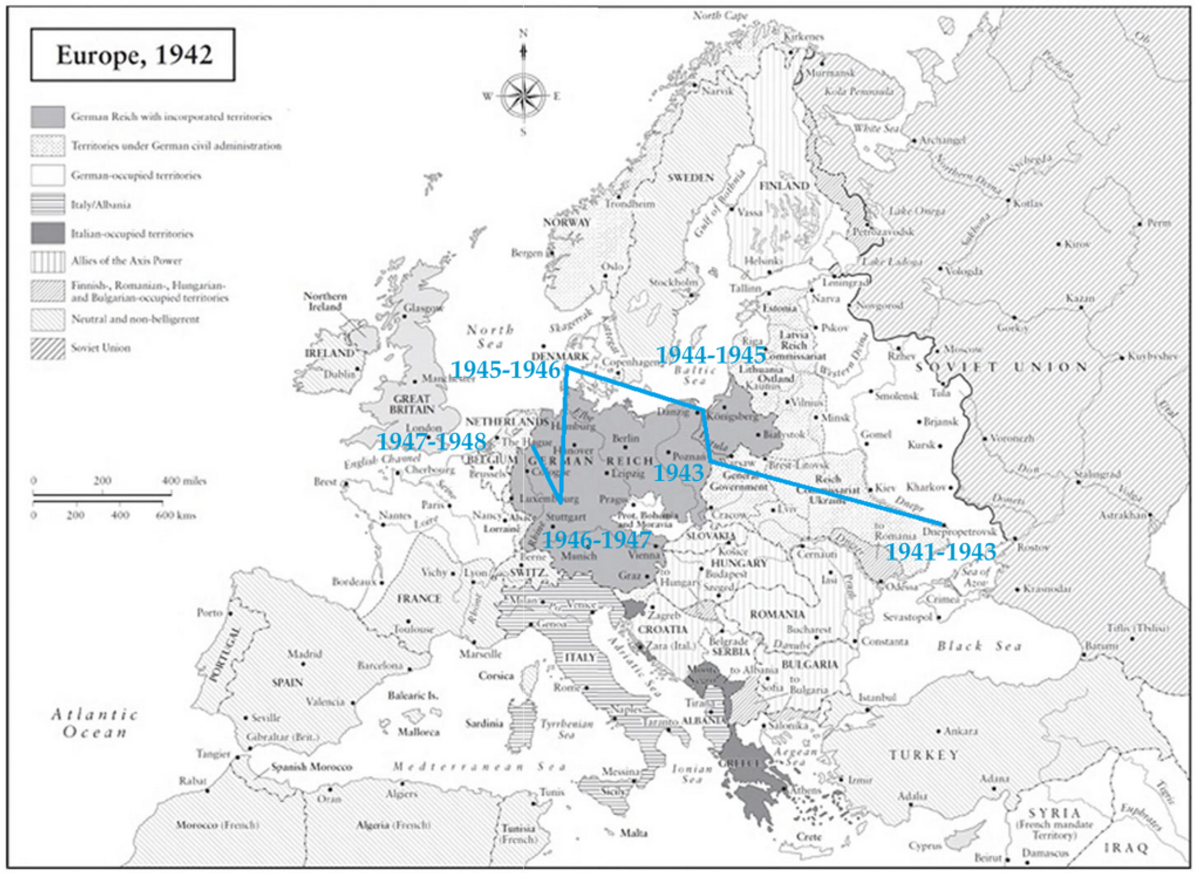

Piecing together Hamm’s past took many years of laborious sifting through thousands of pages of historic documents. I found pieces of Hamm’s story scattered across half a dozen archives in four countries. The reason this search took so long and required such effort is that Hamm did not want me or anyone else to know his full tale. Collaborating with Nazism made sense to Hamm during WWII, when he denounced Jews in Ukraine, lived in housing confiscated from Holocaust victims in Poland, and helped to administer a factory run with Jewish slave labor from the Stutthof concentration camp. After the war, Hamm was not fully honest even with his own sons.

When he wrote his account of his wartime experiences, Hamm was 54 years old and a leader in the Mennonite church with deep ties to the denomination’s respected aid community on both sides of the Atlantic. The United Nations took Hamm at his word. We today, however, should take a more skeptical look.

I now know that Hamm was born in czarist Russia in 1894. He served as a medic in the First World War and took up arms as part of a self defense unit during the Russian Civil War, abandoning pacifism like many other young Mennonite men. When Bolshevism emerged victorious, Hamm lost his farm near the Ukrainian city of Zaporozhe. He and his family moved to another city, Dnepropetrovsk, after Stalin’s rise. Hamm continued working in Dnepropetrovsk after the Nazi invasion of 1941. He eventually left Ukraine with his family, and in 1944, they settled in a village called Stutthof on the Baltic coast.

A document I encountered while researching Mennonite history prompted me to suspect that the postwar autobiographical sketch Hamm penned for MCC might obscure more than it revealed. This other document had been written shortly after Hitler’s invasion of Soviet Ukraine by an “Ethnic German Heinrich Hamm.” Preserved in the records of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories, the six-page typed manuscript tells of horrors experienced under “Jewish-Bolshevik rule.” It describes how young men were shot or deported and how mismanagement brought economic ruin to all Ukraine. The author was unsparing in his conviction about whom to blame:

This is how the Jewish Bolshevik beasts destroyed German families [during communist times]. The expression ‘beasts’ is not even correct, since animals kill for the sake of nourishment, while these Jewish murderers and misbegotten bastards kill and annihilate for sport, practicing the worst kind of cruelty as their life’s handiwork.

Could these be the words of an upstanding pillar within the worldwide Mennonite community? When I first saw this document, I was not convinced it had been written by the same Heinrich Hamm. Hamm was a common surname among Ukraine’s Mennonites and Heinrich was a common first name. Surely there were multiple Heinrich Hamms. Nor was I sure that the author was even Mennonite at all. His report to Nazi officials mentioned other people with names common among Mennonites, but the document referred only to “Ethnic Germans,” not to Mennonites explicitly. Given the repression of Christianity in the Soviet Union in the proceeding decades, perhaps the author no longer identified with what had likely been his childhood faith.

I wondered, moreover, what should I make of the virulent anti-Semitism of this wartime Heinrich Hamm? Most published literature I had read about Mennonites in Ukraine claimed that they had not been particularly anti-Semitic. One historian characterized anti-Jewish prejudices among this group as “relatively benign.” But Hamm’s anti-Semitism was unrelenting. The report stated that Hamm lived in Dnepropetrovsk. Less than a month earlier, Nazi death squads shot 10,000 of that city’s Jews. The murder of Jews around him made Hamm’s concluding remarks chilling: “Only those who experienced [Soviet tyranny] can fully grasp the phrase, ‘Liberation from the Jewish yoke of Bolshevism,’ in its truest sense.”He finished by praising Hitler and all German soldiers.

My next clue was a 1943 letter—also penned by a “Heinrich Hamm”—posted from a refugee camp in Nazi-occupied Poland. This letter seemed to provide a link between the Hamm who had denounced Jews at the height of the Holocaust in Ukraine and the man who subsequently worked for MCC, claiming after the war that Mennonites were an un-Nazi group that suffered under the Third Reich. The author of this letter was clearly a Mennonite who had relocated westward with other Mennonites from Ukraine to escape the advance of the Red Army. The author said he had traveled from Dnepropetrovsk, and details of his story overlapped with the account written two years earlier for Nazi occupation officials by a man of the same name in the same Ukrainian city.

The 1943 letter convinced me that Heinrich Hamm was not only a practicing Mennonite; he was a denominational leader. It also confirmed that this man—who would go on to work for MCC—was implicated in Nazi crimes.

Hamm and his family were among the first Mennonite refugees to be relocated from Ukraine to Nazi-occupied Poland after the contraction of the Eastern Front. Temporarily housed near the city of Litzmannstadt in the wartime Wartheland province, Hamm wrote to a contact well-connected with other Mennonites across the Third Reich. Copies of his letter soon circulated widely among the country’s church leadership. Part of Hamm’s letter even appeared in print, helping inspire humanitarian support for the refugees arriving from Ukraine.

Hamm reported that he and fellow refugees from Ukraine had been well received in Warthegau:

“Upon arrival, we experienced unexpected love and a moving reception. Our camp—if it can even be called that—lies in the forest near Kirchberg (14 km. east of Litzmannstadt) and consists not of barracks encircled by barbed wire, as many expected, but of beautifully appointed houses (formerly for Jewish summer vacationers).” Hamm acknowledged that not all were satisfied with their new quarters. But he disparaged complainers as racial dregs. The “true Germans,” he wrote, “thank God and the Führer daily with tears in their eyes for the great privileges they enjoy.”In other words, in Hamm’s view, the best Mennonites were those most thankful to receive plunder from murdered Jews.

Far from receiving criticism from Germany’s Mennonite leadership, Hamm’s 1943 letter helped integrate him into the local denominational fold. Mennonites who had lived in Germany since Hitler’s rise to power had enjoyed the privileges of racial hierarchy for over a decade. That these same advantages would be extended to fellow German-speaking Mennonites from Ukraine in the form of homes and goods taken from Holocaust victims seemed only natural by the middle years of the war.

Hamm was intimately acquainted with Mennonite life in Ukraine, and he had ties to occupation officials. When religious leaders from Germany traveled to Poland in 1944 to meet with Nazi politicians about new waves of refugees from the East, they first consulted Hamm.

By early 1944, Hamm and his wife, Anna, had moved from the formerly Jewish summer camp near Litzmannstadt to the coastal town of Stutthof, 200 miles to the north. Stutthof had a long-standing Mennonite population, including one of Anna’s aunts.

In Stutthof, Hamm became friendly with a prominent Mennonite businessman named Gerhard Epp. Prior to the First World War, Epp had worked in Russia, and he remained greatly interested in Mennonite coreligionists from the Soviet Union. Epp offered Hamm a job in a large machine factory that he owned and operated—the same establishment that Hamm would later mention in the memo he wrote for MCC, claiming he was coerced into providing cheap labor for greedy German war profiteers.

Three years after the Third Reich fell, shortly before boarding an airplane bound for Canada, Hamm wrote a long letter to his two sons. They had been serving in German uniform, and both had gone missing in the last months of the war. Hamm did not know when or if he would ever see them again, so he left his letter with a local Mennonite leader for safekeeping, hoping that if either of his sons ever resurfaced they would read it. Hamm’s letter is dated July 23, 1948. He signed it just days after authoring his self-exculpatory memorandum for MCC.

Hamm’s letter to his lost sons told a very different story than the one he told to the U.N. In the winter of early 1945, Soviet air raids wrought havoc on nearby large cities like Danzig, driving city dwellers to the countryside even as others arrived pell-mell from the East. Gerhard Epp shipped his machinery west and converted his factory into a makeshift refugee camp. Hamm reported that Epp and his entire staff worked frantically to save the needy. The packed factory halls offered good targets for Soviet airmen, Hamm reported, and every bomb that struck the establishment killed or wounded hundreds:

The great number of bodies and the frozen ground made it impossible to bury them, and so specially appointed commandos for clearing away bodies brought these to the concentration camp for gassing [Vergasung].

Hamm seems to have expected his sons to understand the reference to an unnamed concentration camp. Having visited their parents in Stutthof before their final deployment, Hamm’s sons would have known about the large Stutthof concentration camp, which had been established in 1939 in connection with Germany’s invasion of Poland and which over the next five years would become a major site of slave labor and murder in Hitler’s empire of death. Gerhard Epp served as a general contractor for the camp, from which he leased hundreds of prisoners to produce armaments in his factory. Jews and other inmates were the true cheap labor. Hamm helped oversee their slavery and murder.

Hamm later expressed regret for the death and dying that pervaded the Epp factory in Stutthof. Yet he explicitly named only German victims of Soviet air raids, not Jewish concentration camp prisoners who were worked to death in inhuman conditions. “[M]uch, much blood of innocent women and children flowed on Epp’s land,” Hamm told his sons. “Uncountable, nameless dead. … No one asked who they were, where they came from, nothing was recorded.”

Was Hamm helping himself forget about Jews worked to the bone in Epp’s factory by recalling refugees he and Epp tried to save? His use of the word “gassing” suggests this possibility, since bodies of refugees could have been cremated, whereas exhausted Jews would have been gassed.

What is clear is that the Mennonite-owned factory in Stutthof was a place of terror. For hundreds of prisoners enslaved there, the factory’s Mennonite managers were responsible for much of that terror. It is also clear that after the war, Hamm tried to distance himself from this responsibility. He instead emphasized the suffering of his own family, which fled Stutthof in April 1945. As they crossed the Baltic under cover of night, a Soviet submarine torpedoed their ship. Hamm praised God for allowing the damaged vessel to make it to Denmark. The family remained in Denmark for the next 18 months. Hamm emphasized his gratitude for the comfort he found during these lean times through worshiping with fellow Mennonite refugees and other Christians.

Hamm remained in touch with Mennonites in multiple countries during the early postwar years. From Denmark, he wrote to relatives in Canada, who published his communication in a church newspaper. Letters and material goods soon arrived both for the Hamms and other Mennonites in the area. Hamm coordinated this aid, disbursing dozens of food packets from North America to fellow refugees. When his family received permission to leave Denmark for Germany, they lived with Mennonites in Bavaria. Eight months later, the director of a Mennonite Central Committee refugee camp in Gronau, near the Dutch border, invited Hamm to be his deputy. Hamm took the job, and he worked for MCC in Gronau for nearly a year until leaving to join relatives in Canada.

Catching a Mennonite Nazi is not the kind of thing most people can accomplish in their spare time. It is only possible because of the enormous resources that states, universities, and churches have put into building and maintaining archival collections. Accessing these files often requires professional skills, such as the ability to read multiple languages. Guessing when a historical person may not have been telling the truth requires familiarity with what scholars have already written. And following up on such hunches frequently demands financial support from competitive grants. At a time when the humanities are increasingly under pressure, it is more important than ever to affirm the value of institutional support for deep investigative research.

The reach of murderous authoritarian hate movements is often longer than we think. It has included influential leaders within the Mennonite denomination, including within its best-known humanitarian aid organization, MCC. That knowledge alone should justify robust support for academic scholarship in our current time of resurgent global intolerance and strengthen our sense of the importance of safeguarding the integrity of the historical record in the face of official lies.

This essay is reprinted with permission from Anabaptist Historians.

Ben Goossen is the author of Chosen Nation: Mennonites and Germany in a Global Era. He is currently a Max Weber Fellow at the European University Institute in Italy.