Her Name Was Luka

A stunning piece of scholarly detective work, aided by a new database, restores the identity of a Dutch Jewish hero of the Sobibor revolt

During the weeks leading up to the Sobibor revolt of Oct. 14, 1943, its chief spearhead, Alexander “Sasha” Aronovich Pechersky, kindled a friendship with a 20-year-old Dutch woman named Luka. Pechersky, a Soviet lieutenant captured during the Battle of Moscow, was in Sobibor for a matter of days before he began planning an uprising that would potentially release all its inmates. He met with co-conspirators in the evenings to strategize and exchange information. Luka played a crucial role in facilitating those meetings.

In Sobibor, male and female prisoners were permitted to meet in the evenings; in order to distract the guards away from the gatherings of men, Luka sat alongside them, pretending to be romantically involved with Pechersky. A third co-conspirator, Shlomo Leitman, acted as a translator between the two young “lovers.” Day after day, as Pechersky and his fellow rebels elaborated and exchanged information on the details of their uprising, Luka’s presence distracted the guards.

Three hundred Sobibor inmates escaped the camp on the day of the revolt; of those, 57 survived the war, including Pechersky. Living in the Soviet Union until his death in 1990, Pechersky did everything he could to locate Luka. Though he assumed that she died—perhaps during the revolt or sometime before the end of the war—he sought to honor her memory by identifying her real name. But he never succeeded in learning more about her than the few details he recalled from their conversations in the camp.

On Oct. 14, 2022, journalist Rosanne Kropman published an article in the Netherlands’ daily newspaper De Volkskrant titled, “Who was Luka, Muse and Mystery of the Uprising in Sobibor?” Writing on the 79th anniversary of the revolt, Kropman sought out the biographical details of the young Dutch woman. When I read Kropman’s article, I recognized that Luka’s case could provide a test of a database that will eventually include data on Holland’s 110,000 deported Jews. An aggregation of names, numbers, and dates, my database connected Luka’s legend to a name, a family, a photograph and bits of otherwise disconnected documents and testimony that restore a hero to history.

Kropman’s article provides several clues about Luka that she mined from Pechersky’s postwar testimonies: She was a chain-smoking young woman with auburn hair, 18-19 years old, born in Germany and deported from the Netherlands. Also according to Pechersky, Luka had two brothers, both of whom were gassed. She was in Sobibor with her mother. Pechersky also recalled that Luka’s father had come to the attention of the Nazis as a communist early in the 1930s. Luka proudly told Pechersky how she had been questioned extensively by the police as a little girl, but never revealed her father’s whereabouts: Pechersky would later say in his testimonies that this had made him feel like he could trust Luka.

Information about Luka’s father was key to identifying her name and family. Based on historical testimony, Kropman had assumed that Luka’s father was not in Sobibor, but a detail Pechersky remembered had me doubt this. Pechersky testified that shortly before the uprising started, Luka gave him a buttoned shirt that used to belong to her father. If her father was never in Sobibor, how did his shirt come into Luka’s possession? Upon arrival, prisoners were instructed to leave their suitcases and belongings behind. After they were selected for work or murdered, their belongings were taken to the sorting barracks by Jewish prisoners employed in the camp.

However, the small group of new arrivals selected to work on the day that Luka arrived in Sobibor were allowed to keep the clothes they were wearing; they did not change into prisoner uniforms as inmates did in Auschwitz, for instance. Unless Luka was wearing her father’s shirt herself that day—which is of course not impossible, but unlikely—she must have obtained it later: probably in the barracks where she had to sort through the clothes and belongings of the newly arrived transport. Therefore, I considered it possible that Luka’s father was indeed in Sobibor and that he, possibly together with Luka’s brothers, was sent to the gas chambers after arrival, while Luka and her mother were allowed to live.

The possibility that Luka’s father was with the family allowed for expanding the search to families who were deported in their entirety to Sobibor. Of the several young women in my database who were born in Germany between 1921 and 1926 and deported without both parents, none had names that lent themselves to the nickname of “Luka”: Ruth, Fanny, Irmgard, Gerda … Moreover, on closer examination, other factors about their circumstances had failed to line up with those of Luka: Some girls had been living in the Netherlands without parents, in the case of others, the Nazis had grabbed their mother and had already sent them to Auschwitz in 1942; yet others were only children or are daughters of families with only sisters. Even the few details I entered into the database for each victim were enough to exclude them from my search for Luka’s identity. As my failure to identify Luka continued, I began to doubt the veracity of even the small surviving details that I was forced to rely on.

And then suddenly, when I used my search function to trace all women born in 1923, I found her on the transport list of March 17, 1943: Liselotte Karoline Rosenstiel, born exactly 20 years earlier in Neustadt an der Weinstrasse, Germany. This picturesque town of 20,000 inhabitants at the time of Liselotte’s birth lies in the center of the German wine industry, and had a small Jewish community. In 1927 it became the seat of the Gauleiter for the Nazi party.

Liselotte was deported to Sobibor on her birthday, together with her father, Wilhelm, her mother, Irma Rosenstiel-Oppenheimer, and her younger brother Albert. My eye falls on the composition of her two first names. Liselotte Karoline. Li-Ka. Lika. Could that have been understood as Luka in Sobibor’s phonetic paste of accents? More importantly, was her father a communist?

A Google search of “Rosenstiel Neustadt” reveals how the Rosenstiel family of Neustadt was contending with the Nazi menace for almost 20 years by the time they are deported in 1943. In a recent piece about National Socialism in Neustadt, Gerhard Wunder describes a set of brothers, Julius and Wilhelm Rosenstiel, who took over the family’s wine business after the death of their father. A 1926 issue of the Nazi newspaper Der Eisenhammer called one of the brothers a “traitor,” “adversary of Hitler,” and publicly threatened the lives of Germany’s Jewish citizens. Wilhelm Rosenstiel, the article continues, is “a Jew and separatist,” who “should have been hanging on a lamppost a very long time ago.”

According to Wunder, after 1933 it became too difficult for the brothers to remain in Germany. Their wine business collapsed because of the Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses, and they were faced with criminal charges, for crimes having to do with currency. Julius was sentenced to five days in prison and a 300-Reichsmark fine. Wilhelm was acquitted, but realized that his days in Germany were numbered. He began to sell his possessions with the aim of moving abroad. At the end of December 1935, another arrest followed. In the autumn of 1937, he left for the Netherlands, where he and his family settled in Rotterdam.

According to my database, Liselotte Karoline did not have two brothers that Pechersky reported about Luka; she had only one brother named Albert. But could that possibly have gone wrong because of the language barrier? Did a brother who is two years younger become “two brothers” in his limited understanding of the German language? Possibly.

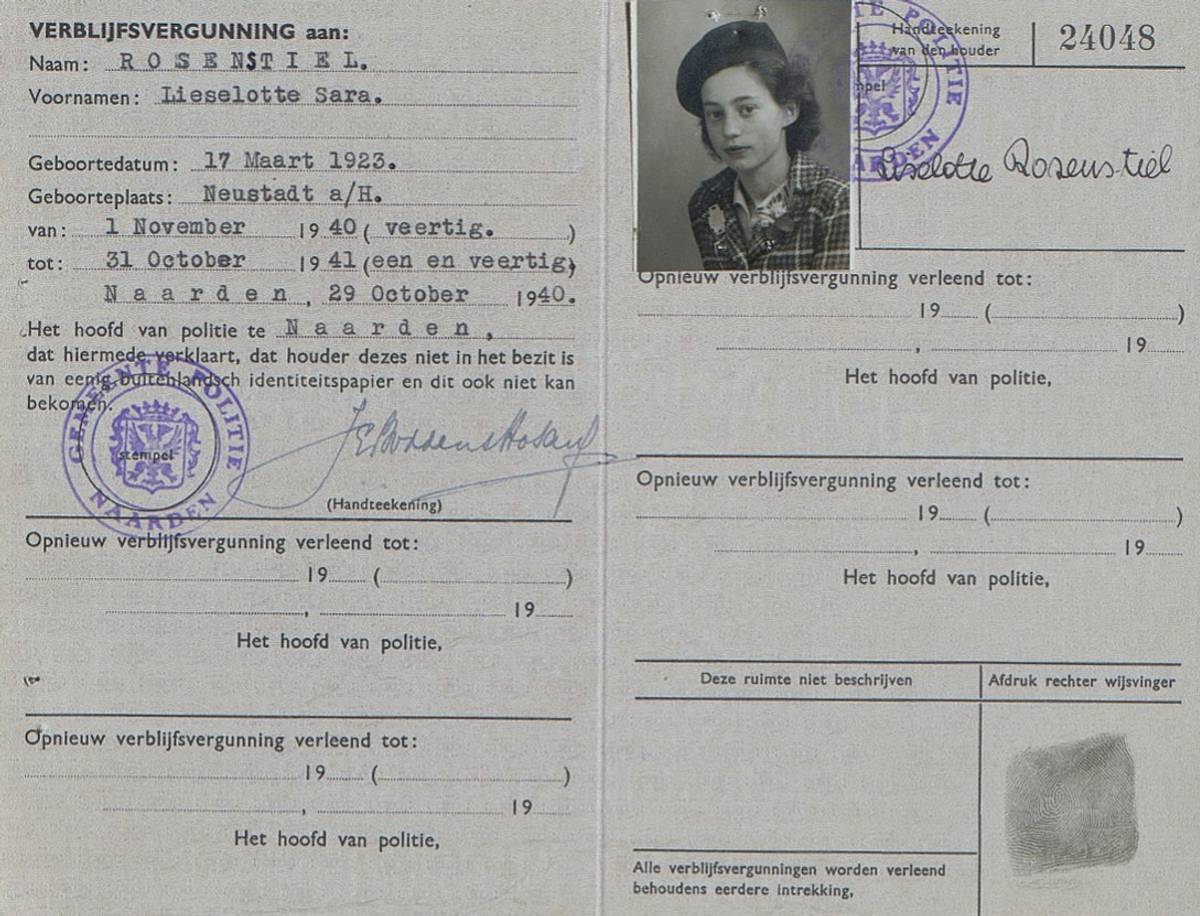

The National Archives in The Hague contains thousands of personal files of Jewish and non-Jewish immigrants who entered the Netherlands between 1918 and 1945. Two weeks after I made a request, an archivist there locates a single Rosenstiel file belonging to Liselotte Karoline. The next day, I enter the light, modern building next to The Hague’s central train station. I know there is a good chance of the file containing photos: Most of these immigration records do. While this photograph will likely be in black and white, it can still be helpful: If that photo shows a very blond lady, then we can safely conclude that Liselotte was not Pechersky’s muse.

The file is not very thick: The Rosenstiel family only came to the Netherlands in 1937 and, apart from some standard forms, not much was recorded. What is surprising is that Liselotte has her own file. Normally, minor children are in the file with the father. To my delight, Liselotte’s file turns out to contain no fewer than two passport photos: The first, stapled to her residence permit, was taken in 1939, a year before the Nazis conquered the Netherlands. Liselotte—16 years old—with a neat beret and a floral corsage on her checkered blazer looks shyly into the camera. She still has the face of a child. Two years later she appears more mature: The wiry girlishness is gone. We see a dark-haired young woman who looks calmly into the distance, her flowered dress just visible.

The file is public because the person in question is no longer alive. Because privacy laws no longer apply, I’m allowed to make scans of both photos. When I walk out of the National Archives a little later, I don’t have 100% certainty yet, but at least we can now safely conclude that Liselotte was a dark-haired young woman—just like Luka. When I later colorize the photos online, it does indeed seem that her hair has a brownish-red glow … but of course we can never know how accurate this coloring machine is.

In my research on the Rosenstiel family, I came across an article from the local newspaper Bussums Nieuws of April 10, 2019, about the Dutch resistance family Leenders, who moved from Rotterdam to Hilversum in 1940 after the bombing of Rotterdam. The article is based on a book Annemieke Schaap wrote about her grandfather’s family: Father Toon Leenders worked as a company manager in the wine factory on Rotterdam’s Jufferstraat that Wilhelm Rosenstiel restarted after his flight to the Netherlands. The bombing reduced everything to ashes. Fortunately, Rosenstiel was insured and even got permission from the Germans to start a new factory, on the condition that it be located at least 25 kilometers away from the coast.

In the summer of 1940, Rosenstiel started anew for the second time, in Hilversum. Toon Leenders, once again, became his company manager. Following the arrest of the Rosenstiels, Leenders joined the local resistance.

After I managed to find Schaap, the author of the book, she told me of Toon Leenders’ last surviving son, Ton. “My uncle Ton is 92 years old,” Schaap told me. “He knew the Rosenstiel family well.” I made an appointment with her to meet two weeks later at her uncle Ton’s home in Valkenswaard.

“He’s a little confused today,” she said to me when I arrived at the facility where he lives. But when I enter and we start talking about the wartime, Ton Leenders turned out to be surprisingly sharp and clear. Many memories returned: about Rotterdam, Hilversum, his own family, the bomb fragment he got in his forehead as a 10-year-old boy the scar of which is still visible, and also about the Rosenstiels. “Rosenstiel often came to us in the early morning, when he had been warned about a raid,” says Leenders. The families, both new to the area, often visited each other. He recognized Liselotte immediately when I show him the two photos. “Yes, that’s her,” he says immediately. Seeing her face again after so many years seems to make him emotional.

“Did she smoke?” I asked him later. Ton Leenders nods. “Yes—secretly,” he says, his eyes twinkling. “Nobody could know that, of course.”

We talk on and then I finally throw out the question, “Have you ever heard of her being called anything other than just Liselotte?” That she had a nickname that sounded like Lika or Luka …?”

His eyes immediately light up with recognition. “Yes, Luka. Luka. That’s what she was called at home.” He nods with a firm face. Annemieke and I look at each other, shocked. Suddenly, on a rainy Thursday morning, the circle is complete. Leenders’ testimony was the confirmation I had not dared to hope for: Liselotte Karoline Rosenstiel is, in fact, the mysterious Luka who Alexander Pechersky kept thinking about all his life.

In June 1942 most Jewish residents of Naarden were forced to move to Amsterdam. The Rosenstiels were still allowed to stay in their home at Van Ostadelaan 3, probably because of Wilhelm Rosenstiel’s wine company. The company manager, Toon Leenders, advised the family to go into hiding, but Wilhelm Rosenstiel refused. He only wanted one thing: to build his new business. He was positive about the future, was comfortable wearing his yellow star stitched neatly on his coat. In April 1942, he had his household effects inventoried, a remarkable decision for someone who had been a fervent opponent of Hitler since the mid-1920s and who had already been exposed to the violence of the Nazi regime.

His optimism was entirely misplaced. In mid-October 1942, the family was forced to report to Bussum station and from there, they were taken to the overcrowded Westerbork transit camp, where Rosenstiel began arrangements to get on the infamous Puttkammer list, a false promise of evading deportation in exchange for vast quantities of money. Soon after, the Rosenstiel’s wine company in Hilversum was expropriated.

In February 1943, Wilhelm Rosenstiel applied and received permission for a two-week leave from Westerbork, from which he traveled to Amsterdam with his son Albert, while Liselotte and mother Irma remained behind. During their leave, Wilhelm and Albert Rosenstiel paid a visit to a Jewish tailor they knew, with whom Wilhelm had left a few rolls of cloth before he left for Westerbork, and ordered two suits. When they returned a few days later to collect the suits, there were Germans in the tailor shop: Rosenstiel was charged with withholding capital from the German authorities and arrested. On March 17, the Rosenstiels returned to Westerbork. A few hours later, the train to Sobibor departed with the whole Rosenstiel family on board.

Until now, it was assumed that all four were sent to the gas chambers immediately after arrival three days later. Now we know that Liselotte and her mother, Irma, somehow managed to join the small group of deportees who were selected for work that day. We don’t know exactly how many women were picked; Alex Cohen, the only survivor of the transport, reported in a postwar statement that men and women were separated after arrival, meaning he never saw what happened to the women. The selected men, about 35 in total according to Cohen, were sent back on the train and arrived the next morning at Majdanek, a camp about 4 kilometers from Lublin. The selected women probably remained at least partly in the camp: When Alexander Pechersky arrived there more than six months later, on Sept. 23, 1943, Luka and her mother were still in Sobibor.

According to Pechersky, Luka managed to escape during the uprising. The last information Pechersky received about Luka was that she was seen among a group of prisoners walking toward Chełm, a town about 50 kilometers from the camp. Since Luka Rosenstiel was never heard from again, we can assume that she did not make it to liberation. How and where she died will probably always remain an unanswered question. But at least now, 79 years after her escape from Sobibor, a hero of the Sobibor uprising has been restored to history.

Aline Pennewaard is a Dutch Holocaust historian and a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Haifa.