A Brief History of the Jews of Bukhara and Central Asia

Our ‘History Detective’ columnist maps out the geographic and literary timeline of the Bukharan Jews

For some, “Jews of Central Asia” sounds more intriguing and exotic than “Chinese Jews” or “Tibetan Jews” (who don’t exist). Jews of Central Asia, or Bukharan Jews, are people with last names ending in the Russian -ov or -off, speaking mostly Russian, and trading diamonds in Manhattan. Some of them might tell you that their ancestors lived in Central Asia for more than 2,000 years. The explorer Benjamin of Tudela in Navarra mentioned huge (and exaggerated) numbers of Jews in Khorasan, Ghaznah, and noted Samarkand as a Jewish metropolis, though he did not, personally, visit there. He did not mention any Jews in Bukhara, though. Today, you might also hear that the Pashtun tribes of Afghanistan (not all the Pashtuns are Taliban, but all the Taliban are Pashtuns) have something to do with the Lost Tribes.

So let’s try and make some sense out of it all.

Where Is Central Asia?

Central Asia is the name for what is between the Middle, or Near, East (Levant plus) and the Far East (Chinese coast, Japan, Korea, etc.). When the terms were coined, the room between the Caspian Sea, Southern Siberia, Northern British India, modern Xinjiang, and Tibet was not yet well known to Western explorers, and the term Central Asia meant, basically, “places outside of British, Chinese, Russian, and Qajar-Iranian rule.”

What Is Modern Central Asia?

Today, the term “Central Asia” is applied mostly to the former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Kirgizia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and sometimes Afghanistan, too. All these countries had been populated by Iranian non-Persian tribes in antiquity, and all of them became affected in the last two millennia, in different degrees, by waves of Turkic nomads invading and infiltrating from the north and east.

All the peoples of the former Soviet republics of Central Asia were conceived by Stalin’s linguistic and nation-building engineering. What we know as Kazakhstan today was called “Kirghiz Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic” between 1920-25 and included large swaths of today’s Uzbekistan, and what is now Kirghizia was known as “Kara-Kirghiz Autonomous Oblast” between 1924-25.

The Central Asian Mesopotamia of Oxus/Amu-Darya and Jaxartes/Syr-Darya was populated by settled agriculturists speaking the local variety of Persian (which was promulgated in those parts as late as Muslim conquests replacing local Eastern-Iranian languages) and different Turkic dialects of almost every kind, one of them being close to what was spoken in Chinese Eastern Turkestan (known now as the Uyghur of Xinjiang). Many populations were or still are bilingual or in transition from Persian to Turkic.

Soviet linguistic and nation-building engineers created a Persian-speaking nation of Tajiks while taking from it the Persian-speaking cities of Samarkand and Bukhara; the Soviets also created Uzbekistan, picking the name of the early-16th-century conquerors of the Timurid states of Central Asia, and picking a dialect on which to build the new Uzbek language that was close to those of Chinese Eastern Turkestan. The idea behind these choices was possibly to carve off Eastern Turkestan and annex it to the USSR.

Who Are the Jews of Central Asia?

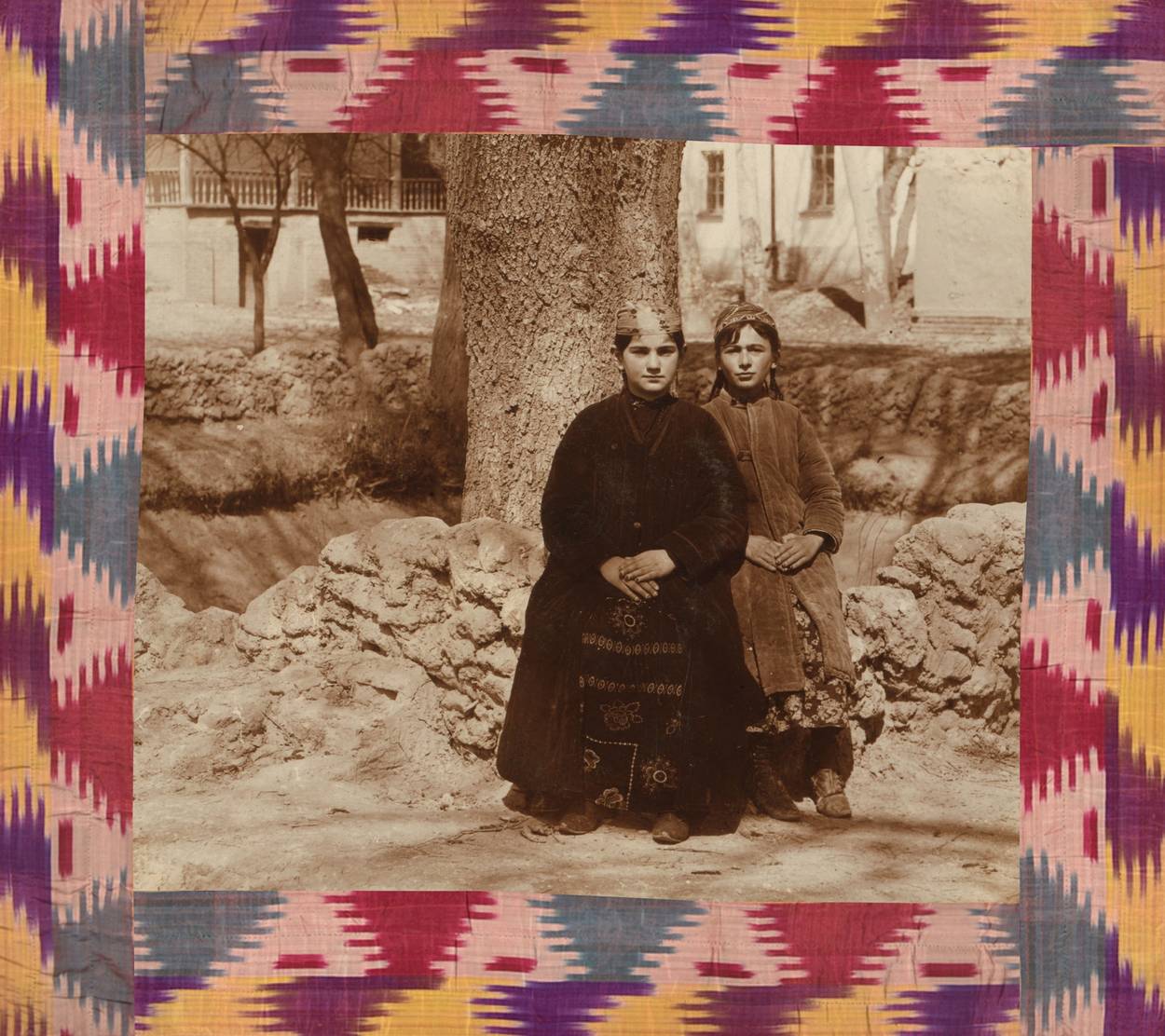

Nowadays, the Jews of Central Asia are either “Bukharan,” because they are descendants of the former subjects of the Emir of Bukhara, or else they are Ashkenazi Jews who settled there in the Russian Imperial period beginning in the 1860s, with the addition of political deportees in the Soviet period and Polish refugees who were fleeing Hitler.

The Bukharan Jews spoke (and some still speak) the local variety of Persian, being urban folk (the cities used to be Persian-speaking). In the second half of the 20th century, they mostly switched to speaking Russian—similar to the ways that Arabophone Jews switched to French in North Africa and the Levant.

How Long Have Jews Actually Lived in Central Asia?

It is possible that some Jews were living in the eastern parts of the (former) Achemaenid satrapies by the time the Book of Esther was composed. The Babylonian Talmud, Avodah Zarah 31b, implies that Jews were living in Marw/Marv/Margiana in the fourth century CE. Jewish inscriptions dating from the Sassanid Period have been found in Baryam-Ali near Marw/Marv/Margiana, though Michael Shenkar tends to ascribe them to a later date.

So, the Taliban Are Not Actually Descended From Jews?

There are both pre-modern and modern legends about the Jewish origins of Pashtun/Pathan tribes in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Unfortunately for lovers of distant cultural correspondences and romantic myths, these legends are baseless. The Pashtun tribes arrived on the historical scene lately and from nowhere, aspiring to a status similar to that of the Persians; their tribal leaders, who were also poets at the same time, invented for them an Israelite origin. “Persians have literature, courtly culture, and food, we are descendants of the people mentioned in the Qur’an.”

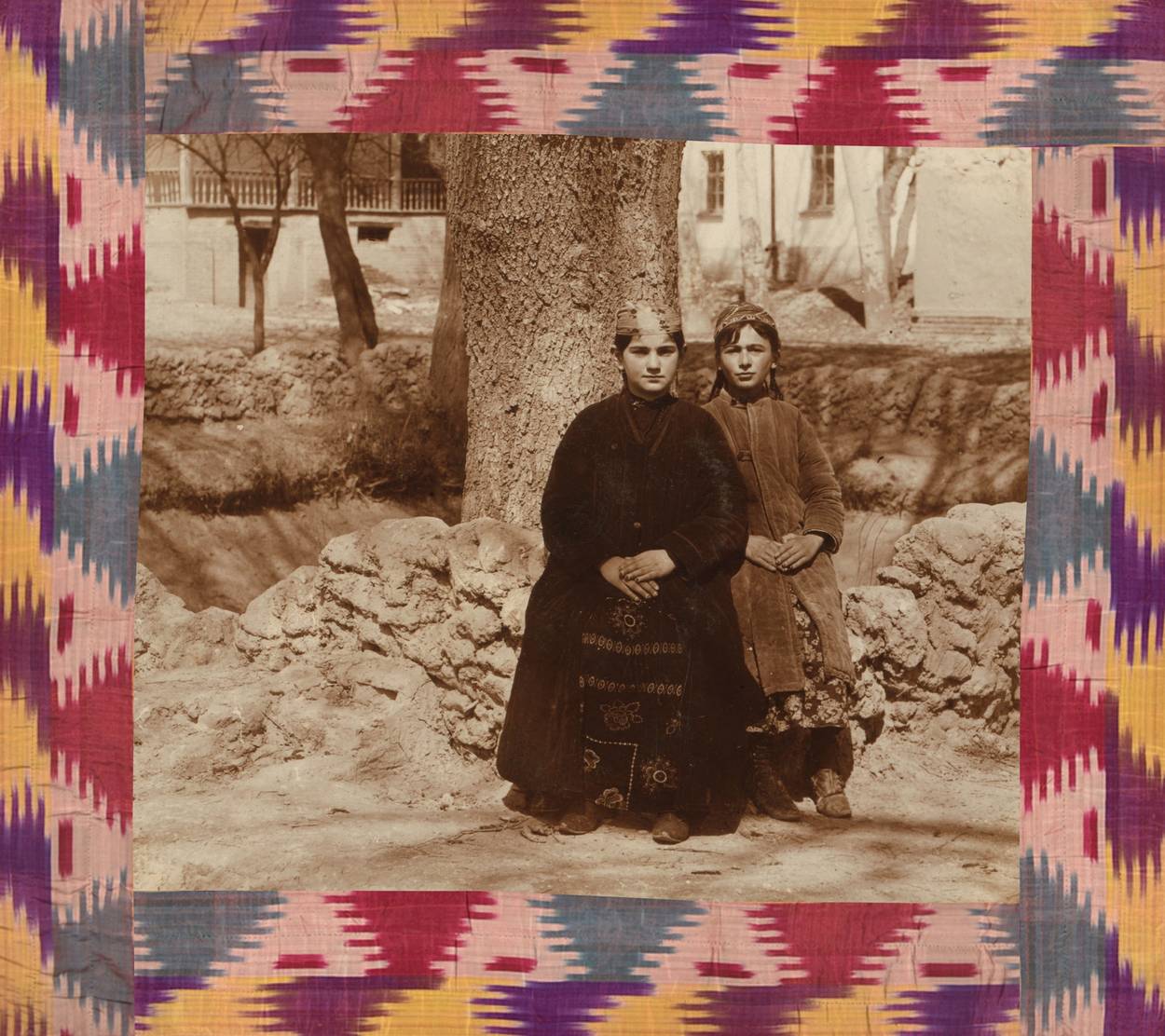

Three stone inscriptions in Early Judeo-Persian were found in Tang-e Azāo in Ḡur Province, Western Afghanistan, Ḡur Province. They were dated 1064 Seleucid Era (752/3 CE).

Jews and the Silk Road to China

Two Early Judeo-Persian letters from the eighth century were found on the Silk Road, in Dandān Öilïq in Western China, the first in 1896, and the second, from the ninth century, a decade ago. As in many other cases of modern languages first recorded in Hebrew characters, Early Modern Persian is first documented in these private Judeo-Persian letters found on the Silk Road. A Jewish community existed in the Chinese capital of Kaifeng under the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127), to which Jews arrived from the Persian-speaking world, as is evident from the Judeo-Persian rubrics in their prayer books. Jewish historical stelae in Chinese were erected in Kaifeng in 1489, 1512, and 1663.

The Jewish participation in trade through the northern route of the Silk Road was part of the push of multireligious Sogdian merchants and missionaries from Central Asia into China. Sogdian merchants on the Silk Road were divided into several religions—Manicheans, Nestorian Christians, a variety of Zoroastrians, and Buddhists. Dharmaguptaka and Sarvastivada Buddhism seem to have been prevalent in Central Asia and some traces still survive in the Far East. In fact, the name of Bukhara is Sanskrit for “a Buddhist monastery, vihāra.”

China got her Buddhism mostly from the peoples of Central Asia. Manichaeism, Nestorian Christianity, and Judaism also made their way to China, to become Sinicized in due time. Many Sogdian documents were found on the Silk Road, though few in Sogdiana proper. A Chinese source tells about Sogdians that they are a curious people interested in two things only: money and religion. For these two reasons, they leave their own countries and travel to foreign lands where they spend many years.

There is a story about a father and his son, members of a very well-known Bukharan Jewish family. The father took his 14-year-old son to Shanghai (during what appears to be the 1930s), they crossed the street, the father took out of his pocket a sheaf of bills and gave them to his son saying, “I owe you nothing now; do it your own way,” added a blessing, and crossed back to the other side of the street. His son, who spoke no English and no Chinese in Shanghai, eventually became a well-known millionaire. This is a very Bukharan story; but it sounds like a Sogdian story, too.

Hiwi ha Balkhi and the Jews of Khorasan

Mā Shā’ Allāh ibn Athari (circa 740-815) was an astrologer, astronomer, and mathematician of Jewish extraction from Khorasan. Ḥiwi (or Khvayweih?) ha-Balkhi was somehow connected to the city of Balkh (formerly, the capital of Bactria), which is now in Afghanistan. A rationalist critic of Judaism, Hiwi lived in Khorasan in the ninth century. His book seems to have been written in versed Hebrew, as we can judge from fragments quoted by Sa’adia Gaon who dedicated a refutation to Ḥiwi’s book.

It is uncertain whether Ḥiwi was a heretical antinomist Jew or a Gnostic Christian possibly of Jewish origin. Either way, he is seen by scholars as the first in the line of those engaged in Bible criticism, and his views were taught by Jewish schoolteachers for several generations. Hundreds of years after his death, he was still called ’l-klby (the doggish one, a pun on ’l-blky, that of Balkh). One Karaite author made Ḥiwi the teacher of the ninth-century freethinker archheretic, the second-generation Muslim of Jewish extraction, Ibn Al-Rawāndi (827-911).

The son of a Jewish convert to Islam, Shahid Jahudanaki Balkhi (d. 935) was an early poet in New Persian, a follower of Rudaki, as well as a Sufi philosopher; he was one of the court poets of the Samanid Emir Nasr I (r. 864/5-892). The Jerusalem-born Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi (946/7-1000) noted that Khorasan possesses more scientific and religious knowledge than any other Muslim country, and that there are in Khorasan many Jews and few Christians (though we know much about Nestorian bishops at Marv and possess their full-length books written in Syriac).

The Karaite Daniel al-Qumisi (d. 946) mentioned Karaites in Khorasan. The “Jewish-Khazar Correspondence” and the subsequent literature mentioned Jewish emigration to Khazaria from Khorasan. The largest known text in Early Judeo-Persian, the Tafsīr of Ezekiel, was composed not earlier than 944 CE, likely partly in Northern Afghanistan. This composition is probably “Karaite” of sorts and was copied in the early 11th century.

The End of the Persian-Speaking Jews of Central Asia

The Jewish cemetery near Ğur/Firuzkuh, in Northern Afghanistan, was in use for two centuries between 1012/13-1218, with inscriptions made in Judeo-Persian, Hebrew, and Aramaic. The Firuzkuh Jewish community was eradicated, together with other Jewish and Christian communities of Central Asia, with the invasion of the region by the Mongols. The Mongols did not single out Jews or Christians as such, they simply razed cities that tried to resist and destroyed their entire populations. Those who gave in were generally spared.

In general, the history, languages, and cultures of Greater Iran, Iraq included, and Eastern Europe can be sharply divided into the pre-Mongol and post-Mongol periods. As with the pre-Mongol writing tradition of Judeo-Persian, there was no continuation into the Mongol period. Everything would begin again from a fresh, much lower, start.

Some Books Survived, Though

An important Hebrew midrash on the Pentateuch, the partly preserved Pitron Torah, was copied in 1328 in the city of Sambādagān (city of those of Sabbath). In the same year, Shahin-Torah, a poetic paraphrase of the Pentateuch in Judeo-Persian, was copied somewhere in Central Asia, the year after the work had been composed.

The Hebrew-Persian dictionary containing about 18,000 Hebrew and Aramaic words, Sefer ha-Meliṣah by Shlomo ben Shemuel, was written in the city of Urganj (Gorganj) in 1339. The work is titled Agron. Jews most likely lived in the area of Kabul, as can be surmised from a tomb inscription of 1365 (though this might be a forgery).

The New Jewish Community of Bukhara

When Tamerlane/Timur-Leng (r. 1370-1405) made Samarkand the capital of his empire, he brought there many thousands of carpet weavers, silk dyers, artisans, and merchants from many cities he had conquered, and among them some Jews and Christians from Kurdistan and Northern Syria. In Samarkand, the Jewish deportees adopted the Eastern Persian idiom of the local Jewish (and Muslim) inhabitants. Those Jews, who shaped the character of the community, would much later be known as “Bukharan Jews.”

The renewed Jewish settlement in Bukhara seems to have occurred in the early 17th century, since the first synagogue was built there in 1620. In 1606, Khvāja Bukhārāʾi composed a religious verse epic in 2,175 couplets based on the Book of Daniel, the Apocrypha, and the midrashim; it contains Rabbi Saʿadia Gaon’s calculations about the coming of the Messiah. In 1704 Binyamin ben Mishāel, or Aminā, reedited the text and inserted several of his own verses in it. In 1725, a book written in Italy was copied in Bukhara; a kabbalistic work copied in Marv in 1775 testifies to the region’s ties with the West.

Nowhere in the diaspora were the conditions in which Jews were made to live so sadistically cruel, so absurdly humiliating, as in Central Asia between the 17th and mid-19th centuries. It should be observed that many Jews of many Jewish communities bear multigenerational traumas, but the majority of Bukharan Jews are not even aware of theirs.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, there were numerous cases of forced or semiforced conversions of Jews to Islam in Khivah and Bukhara; the converts and their descendants are called Chala and were (and still are) ostracized by both Jews and Muslims. It seems that in the last two or three decades, all of them emigrated from Uzbekistan to Russia in order to avoid discrimination and find better lives.

Yosef Maman and Zekhariah Maṣliaḥ Arrive in Bukhara

In 1793, a fundraiser for the Jews of the Land of Israel, the Morocco-born Yosef Maman (1741-1822), arrived in Bukhara and decided to stay there. He found many irregularities in the life of Bukharan Jews, like the use of the Sabbataean book Ḥemdath Yamim (pr. 1732/3) in the synagogue service, the ignorance of the Shulḥan ‘Arukh, the absence of miqveh, and many more.

Fighting his rival fundraiser, the Yemenite Zekhariah Maṣliaḥ, Yosef Maman managed to reorganize and reform the community, changing their Persian prayer book and bringing them to the Spanish (Sepharadi) ritual and Halachic norms. His descendants provided leadership for several generations. In 1802, some Bukharan Jews at Qizilgar tried to establish contacts with the short-lived rich maskilic community of Shklov (in today’s Belarus), asking them in their letter: “From which one of the Lost Ten Tribes are you there in Shklov?”

In the early 1820s, Jews of Bukhara tried to have Jewish books printed in the Russian or Ottoman empires; copies of the Hebrew New Testament sent by Scottish missionaries from Orenburg, Russia, were burned by local rabbis. Yakov Samandar, the Bukhara-born son of an immigrant from Izmir (or Smederevo in Serbia?; or Enderi in Daghestan?), imported books from different places, and had three Hebrew books printed at Leghorn, Shklov, and Vilna for the Jews of Bukhara.

In 1827, David b. Hillel of Safed visited Bukhara in order to raise funds for the Land of Israel. Since then, Jews of Bukhara began to settle in the Holy Land (the first wave of immigration of Bukharan Jews to the Holy Land took place between 1827 and 1868). Around this period, there were some vague reports about Jews from Bukhara who had gone to China, but all contact with them was lost.

Joseph Wolff, an Anglican Missionary, Arrives Too

In the early 1830s, some cities of Central Asia were visited by Joseph Wolff (1795-1862), a Jewish German convert to Christianity who became a British Anglican missionary. It was Wolff who popularized the view that the Jews of Central Asia were an exotic group of immense antiquity cut off from the rest of Jewry for ages, somewhere in the midst of savage Tartary (Wolff 1835).

The First Golden Age of the Bukharan Jews Begins!

In the framework of The Great Game, the Russian Empire conquered most of Central Asia between 1864-1872. Between 1865-1868, Russian forces under Generals Cherniayev and von Kaufmann conquered Tashkent, Khodjend, Samarkand, as well as the Khanate of Qoqand/Xoqand/Qoqon and the Emirate of Bukhara. The governor-generalship of Russian Turkestan was established; Emirate of Bukhara was reduced in size and made a Russian protectorate; Samarkand became a Russian city; and the Khanate of Qoqand was abolished in 1876 and annexed to Russia. The Khanate of Khiva was much reduced in size and became a Russian protectorate in 1873. Thus, the Golden Age of the Central Asian Jews began.

In territories under direct Russian rule, Jews enjoyed personal liberties and economic opportunities unheard of under the ancien régime. Jewish families made big fortunes on trade with Russia proper, India, Persia, and Western Europe. The growth of the community attracted immigrants from Meshhed (Muslim crypto-Jews) and Afghanistan, where in 1885, the government confiscated the property of 250 Jews and expelled them, with their families, to Termez, wherefrom they proceeded to Samarkand. It also attracted Baha’is from Persia, some of whom were former converts from Judaism.

Ashkenazi Russian Jews also settled in the Russian-ruled cities. To differentiate the “European” Jews from the “Native Jews,” the term “Bukharan Jews” was coined. Many Chala people moved from the protectorates to Russian territory, sometimes trying to reconvert to Judaism.

By the last quarter of the 19th century, Samarkand became once again the community’s main center, because under direct Russian rule it offered better conditions for life than the Bukharan Emirate.

A New Judeo-Bukharan Literature Is Born

During this short period of unprecedented prosperity under Russian rule, the Jews of Central Asia also enjoyed a cultural revival, both in Samarkand and in Jerusalem. Shim‘on Hakham, the first-generation of Persian speakers (his father came from Baghdad), and others created the New Judeo-Bukharan literature in Jerusalem. The Book of Psalms, translated by Benyamin ben R. Yoḥanan ha-Kohen, was published in Vienna in 1883 with Hebrew text and Persian translation on facing pages. In 1885, he translated and annotated the Book of Proverbs, using the translation he had received from his rabbis.

In 1889, the new wave of immigration from Samarkand to the Holy Land began, being thus the third “modern” wave of ‘aliyah in the 1880s. In 1891, a new neighborhood—Rehoboth, or Rehoboth ha-Bukharim—arose in Jerusalem, with some 500 persons participating in the project. The neighborhood would evolve into the famous Bukharan Quarter of New Jerusalem, a beautifully built area with “palaces” of rich merchant families.

In this area, publishing houses were also established, supplying books in “Persian current in Bukhara and its precincts,” in Hebrew characters, to Jews of Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Persia. Bābā-Jān b. Pinḥas of Samarkand translated the Book of Job into this variety of Judeo-Persian and published it in 1895 in Jerusalem. The most prominent figure of the Judeo-Bukharan literary activities in Jerusalem was Shim‘on Ḥakham (1843-1910), the son of a newcomer from Baghdad and a descendant of Yosef Maman, who translated and edited a whole range of books, from traditional tafsirs to adaptations of European classics.

The short flourishing of the Judeo-Bukharan culture, which was markedly distinct from both that of the Jews of Persia and that of the Jews of the Russian Empire, was brought to an abrupt end by the First World War. The subsequent Bolshevik takeover of Central Asia cut off the Bukharan community in Jerusalem from their brethren in Central Asia—the sources of their previous income.

The Bolsheviks Meet the Jews of Central Asia

At first, the Bolsheviks and their Russian Jewish cultural and social “engineers” were willing to recognize the right of non-Ashkenazi Jewish groups, namely the Jews of Bukhara, Daghestan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and the Crimea, to develop their own forms of cultural and linguistic expression. It is important to note that the literary language of the Bukharan Jews, which was different from the local Central Asian literary Persian, preceded by decades the emergence of Soviet-Tadjik. On Feb. 10, 1925, the Uzbek Soviet leader Yuldash Akhunbayev recognized the “native Jews” as an “ethnic group.”

In the first half of the Soviet rule over Central Asia, the Jews of Bukhara, Samarqand, and other places found themselves in a difficult sociolinguistic situation: the cities they were living in were Persian-speaking (“Tajik-speaking,” in the Soviet parlance), but allotted to a new “Uzbek” Soviet state, with a Qarluq-Turkic language akin to Uighur, with a Qıpčaq name and with Navā’ī (1441-1501), a Čaghatay poet and a sworn enemy of the Özbek invaders, as the national bard.

The Persian-speaking (“Tajik-speaking”) populations of the big cities and countryside in Soviet Uzbekistan thus came under heavy pressure to become Uzbekized. The Soviet recognition of the “native Jews” as a separate ethnic group gave the Jews, for a decade or so, an opportunity to develop (and Sovietize) their already existing literary language, while the stress was put on its differences from the developing Soviet variety of Central Asian Persian, dubbed “Tajik.” In this respect, the linguistic evolution of this non-Ashkenazi Jewish community was unique in the USSR.

In the 1920s-1930s, many Bukharan Jews managed to escape the USSR. They settled in the British Mandate of Palestine and, sometimes, in Afghanistan and Iran and elsewhere. A turning point for the remaining Bukharan Jews was the Second World War. As part of the evacuation of industries and population behind the Urals, many thousands of non-Muslims found themselves in Central Asia, above all, in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Most of these migrants were “Slavic,” but there were members of quite a few other groups, including Koreans, and also many Jews—a great number of whom were undraftable Hasidim from the newly occupied eastern parts of Poland. The Jewish presence among the evacuees was so prominent that it gave rise to an anti-Semitic slur: “Jews are fighting on the Tashkent front.”

The interaction between the Polish Jews, many of whom were Lubavitcher Hasidim, and the Bukharan Jews, who were already far more traditional by Soviet Jewish standards, brought about a unique strengthening of Jewish identity and Jewish education among the Bukharan Jews, while also forwarding the linguistic Russification among the youth, as Russian became the language of inter-Jewish communication.

In Afghanistan, the large number of refugees from the USSR, both Jewish and non-Jewish, created a crisis in the 1930s, which was accompanied by the rising pro-Nazi sympathies of the government in Kabul, which began to deport the refugees back to the USSR and to Xinjiang. Afghanistan’s Jewish nationals were targeted, too, with most of them restricted to Herat and Kabul. After WWII, almost all the Jews of Afghanistan immigrated to Israel; by 2019 one Jew was left in Kabul. There is a Wikipedia entry and a British play about him.

The Great Soviet-Central Asian Jewish Literary Tragedy of Muhib

The author writing under the pen name Muhib (“lover”), was born Mordechai b. Hiya Buchaev in Mary/Merv, Transcaspian Oblast (Russian Empire), 1911, and he died in Petah Tikva, Israel, 2007. His tragic life was an embodiment of the complex experiences of Bukharan Jewry during its Soviet century.

As a child, Muhib moved to Samarkand with his family, where he learned at a Jewish religious school, a Russian public school, and then at the Teachers Faculty of Tashkent University, where he studied sciences. In 1927, he published his poems at the Judeo-Tajik newspaper Rushnoi (“Enlightenment, Light,” Samarkand). In 1930, he became secretary in charge of the Judeo-Tajik newspaper Bayraq-i Mihnat (“the Banner of Labour,” Tashkent). He published successfully his very Soviet poems Bahor-i Surx (“the Red Spring”) in 1931, and Quvat-i Kollektiv (“the Collective’s Power”) in the same year, then Sado-yi Mihnat (“The Labour’s Voice”) in 1932. He translated for theater from Uzbek into standard Soviet-Tajik and prose from Russian into Judeo-Tajik. All in all, his life looked like a great Soviet Central Asian Jewish success story.

However, in the late 1930s, the Soviet attitudes toward minorities and their cultures changed significantly. For example, the Ukrainian schools in the Kuban region were closed, all Yiddish schools were graduate closed, and Judeo-Tati and Judeo-Tajik ones as well.

In 1938, Bachaev was arrested for “Jewish bourgeois nationalism” and spent 10 years in the gulag, then five years in internal exile/ban (ssylka). In 1953, he was able to settle down in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, where he became a respected translator and editor; at the time, many other Judeo-Tajik/Judeo-Bukharan intellectuals moved from forcibly Uzbekized Bukhara, Samarkand, and Tashkent to the more liberal air of Dushanbe. However, Bachaev’s poems were not published due to political censorship.

After the Six-Day War (1967), Muhib tried to repatriate to Israel but was refused. He was able to reach Israel only in 1973, in the framework of the politics of détente. He settled in Jerusalem and became engaged in broadcasting and editing a bulletin in Judeo-Tajik. In 1974-75 he wrote a two-volume novel, Dar Chuvol-i Sangin (In a Stone Sack), written in a manner recollecting Vassily Grossman’s Forever Flowing and Life and Fate. Some found his description of members of the Jewish Bukharan community unflattering.

In 1978-79, Muhib published his older poems, unpublished in the USSR because of censorship and now smuggled into Israel, in two collections, Ghazaliyat and Guldasta. In Israel, he also translated into standard Tajik the Old Testaments from Hebrew, and the New Testament from Russian, for a Stockholm-based project of Bible translations. In 2006, Muhib’s complete works were edited by the now-deceased professor Michal Zand.

Aliyah and Emigration

Since 1972, Bukharan Jews, together with Jews from Georgia and the Polish, Lithuanian, etc. territories annexed by the USSR in 1939-40, as well as from the original Soviet territories, began to immigrate to Israel. With the demise of the USSR in the late 1980s and early 1990s, almost all the Bukharan Jews—about 45,000—left Central Asia to Israel and other countries.

Today, there are about 150,000 Bukharan Jews in Israel and about 60,000 in the United States, mostly Queens. There are great Jewish Bukharan restaurants in Queens (and in the Diamond District), and connoisseurs will travel from as far as Milwaukee and Ann Arbor to eat there. The Judeo-Persian of Central Asia, or “Judeo-Bukharan,” is hardly a living language, though activists in Queens are trying to reverse the wave. About 1,000 Jews live in Uzbekistan, a similar number in Tajikistan, where the government has recently twice destroyed the only existing synagogue. Some Bukharan Jews with Israeli and Russian citizenships still do business in Northern Afghanistan.

Dan Shapira is an interdisciplinary historian and philologist at Bar-Ilan University. He is working currently on medieval and early modern Jewish minority communities, the Crimea, and the Khazars.