Hey, I’m Your Cousin

Tracking the descendants of America’s early Sephardic elite, from WASP blue bloods to the great-great-grandchildren of slaves

Before Family Search and Jewish Gen revolutionized Jewish genealogy, people who thought they might be descendants of early American Jews scanned the fine print of Rabbi Malcolm Stern’s First American Jewish Families for proof of their families’ longevity in the New World. Stern’s volume (it was first published in 1960) charted the genealogical histories of all the Jews who had come to the United States before the Jewish population hit 10,000, in 1840. In his 1971 portrait of “America’s Sephardic elite,” Stephen Birmingham referred to Stern’s volume as “the Book.” Piqued by the notion of Jewish elitism, Birmingham’s The Grandees claimed that Stern’s genealogy distinguished the tiny contingent of Jews whose ancestors came to North America during the colonial era from the mass of latecomers who followed in their footsteps.

Birmingham’s take on Jewish bluebloods alienated the mass of American Jews and embarrassed the very same “Grandees” whose story it purported to tell. Filled with gossipy details about a cast of characters whose rarefied lives in Fifth Avenue’s high castles generated wonder and envy, The Grandees made Malcolm Stern’s well-intentioned effort to shed light on colonial-era Jewish history sound like a Jewish version of a Brahmin social register. Birmingham depicted the progeny of early American Jews as fetishizers of the past, people who “appear[ed] to worship history more than the Judaic God.” Accumulating knowledge about one’s ancestors, however, doesn’t necessarily equate to pettiness or give rise to aristocratic pretensions. Attention to family history also reminds us of the astonishing legacies we inherit from the past.

Identifying the descendants of early American Jews today is a challenging but worthwhile task, and some descendants of historical personages are more difficult to find than others. Keith Stokes is Rhode Islander of African heritage whose Sephardic ancestors take up considerable space in Stern’s book. His people, the Hays and Touro families, helped to found Newport, Rhode Island’s famous colonial-era synagogue in 1763. They also figured prominently in the establishment of Richmond, Virginia’s Beth Shalome congregation in 1789. Because none of his African heritage ancestors’ surnames appears in Stern’s index, however, Keith Stokes is an “invisible” descendant of these Sephardic Grandees. The intricacies of his family story remind us not only of how surprising early Jewish American history can be, but of how the most painstakingly researched genealogical charts don’t necessarily bring us into contact with all of its legatees, let alone its most revelatory truths.

Family history is a dynamic milieu by definition, and family trees grow new branches with every matrimonial liaison. Malcolm Stern may have started small, with a body of information that pertained to 100 families, but mapping out genealogies is a maddeningly multiplicative enterprise. To cite one startling statistic, 35 million people claim descent from the 102 passengers who set sail to Plymouth on the Mayflower! Likewise, a mere 2,000 Jews lived in North America at the time of the Revolution, but Stern’s book contained references to upwards of 25,000 living descendants of America’s oldest Jewish families. Within a short space of time, many of the Jewish “Pilgrims” who came to North America during the 17th and 18th centuries had begun the process of melding their fates with those of their gentile neighbors.

Depending upon one’s perspective, being connected to an ancestor whose name appears on one of Stern’s hundreds of painstakingly researched family trees might be a point of pride, bafflement, or indifference. For Keith Stokes, who spent his childhood and youth in close proximity to the architectural remnants of one of America’s oldest Jewish communities, those genealogical links stipulated an early awareness of historical complexity and paradox. The father of Keith’s Newport ancestor Moses Michael Hays, New York merchant Judah Hays, had owned enslaved Africans. Several of his father’s ancestors, who had come to Rhode Island directly from one of the “gates of no return” in Ghana, were buried in God’s Little Acre, Newport’s (and the nation’s) oldest African American cemetery. The remains of Stokes’ Jewish ancestors lie a short walk away, in the city’s oldest Jewish burial ground.

As Keith Stokes’ story shows, being genealogically connected to one of America’s “first Jewish families” means more than being connected to the early modern diaspora. Like being descended from the Anglo-Americans who settled in North America before the massive waves of 19th- and 20th-century immigration, it means being implicated in stories of conquest and slavery. It is also a reminder of how tangled the skeins of history can be, and of how infinitely capable its principal players were of acting in total defiance of our limited expectations and anachronistic value judgments.

To find Keith Stokes in the first place, I had to let go of a few major assumptions. When I first decided to conduct ethnographic research on the descendants of early American Jews, I imagined that finding people to interview would be a matter of looking up surnames and sending out some emails. I also guessed that people from existing Jewish communities and congregations, especially the ones whose origins date back to the 1700s or earlier, would yield the lion’s share of potential informants, and that those informants would be practicing Jews. I was not as sophisticated in my thinking, in other words, as Malcolm Stern had been. When Stern’s book first came out, he called it Americans of Jewish Descent, thereby acknowledging that not all Americans of Jewish descent were actually Jews. Intermarriage and conversion had, after all, resulted in a large-scale attenuation of Jewish affiliations over time. In some instances, we might say that it also resulted in the spreading of Jewish influence. I found Keith Stokes because he wanted to be found. He had grown up hearing about his Sephardic forebears from his grandmother, who cared deeply about their legacy, despite the fact that she was a devoted Episcopalian. Over the last 20 years or so, Stokes has written fairly extensively about his mixed heritage. It was his website, Eyes of Glory, that brought his family’s story to my attention.

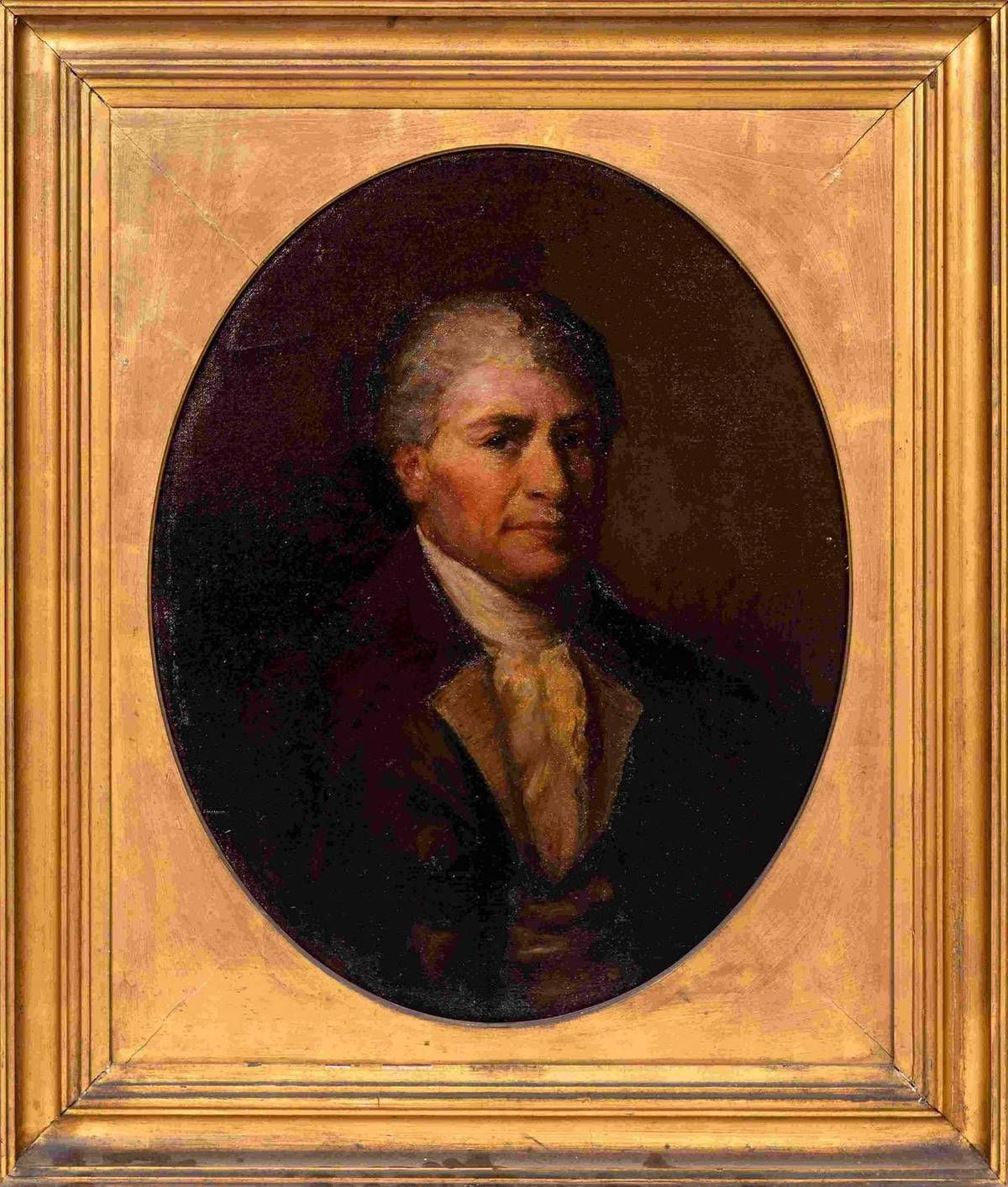

Keith Stokes’ Jewish ancestors included Slowey and Catherine Hays, both of whom were daughters of Moses Michael Hays and Rachel Myers Hays, who left New York to live in Newport from 1770 to 1776. The Hays’ move to Boston during the Revolution marked the first instance of a Jewish family settling in that Puritan-dominated city, but their stay there was short-lived. “When Moses and Rachel die” (in 1805 and 1810, respectively), Stokes recounted to me when I interviewed him, “Catherine and Slowey go to Richmond, Virginia, with [their Scots Irish servant] Excy Gill to join their two older sisters, who had married Moses Myers and Samuel Myers, who are their first cousins.” As the two sisters relocated to a Southern city, the family’s history took an unexpected turn. “They [were] helping to found a congregation there,” Keith told me, and “living in a double house on Broad Street on one side with Excy Gill.” On the opposite side of the house, as he explained, “Moses Myers and his wife, Sally Hays Myers, and their daughters [were] all living together.” One of Samuel and Judith Hays Myers’ children was Gustavus Adolphus Myers, who has been memorialized as, among other things, a distinguished Richmond attorney and board member of the city’s Beth Shalome congregation. As the John L. Loeb Database of Early American Jewish Portraits explains, it was also the case that Gustavus “fathered his first child when he was only nineteen.” The mother of that child, Nelly Forrester, was a free woman of color.

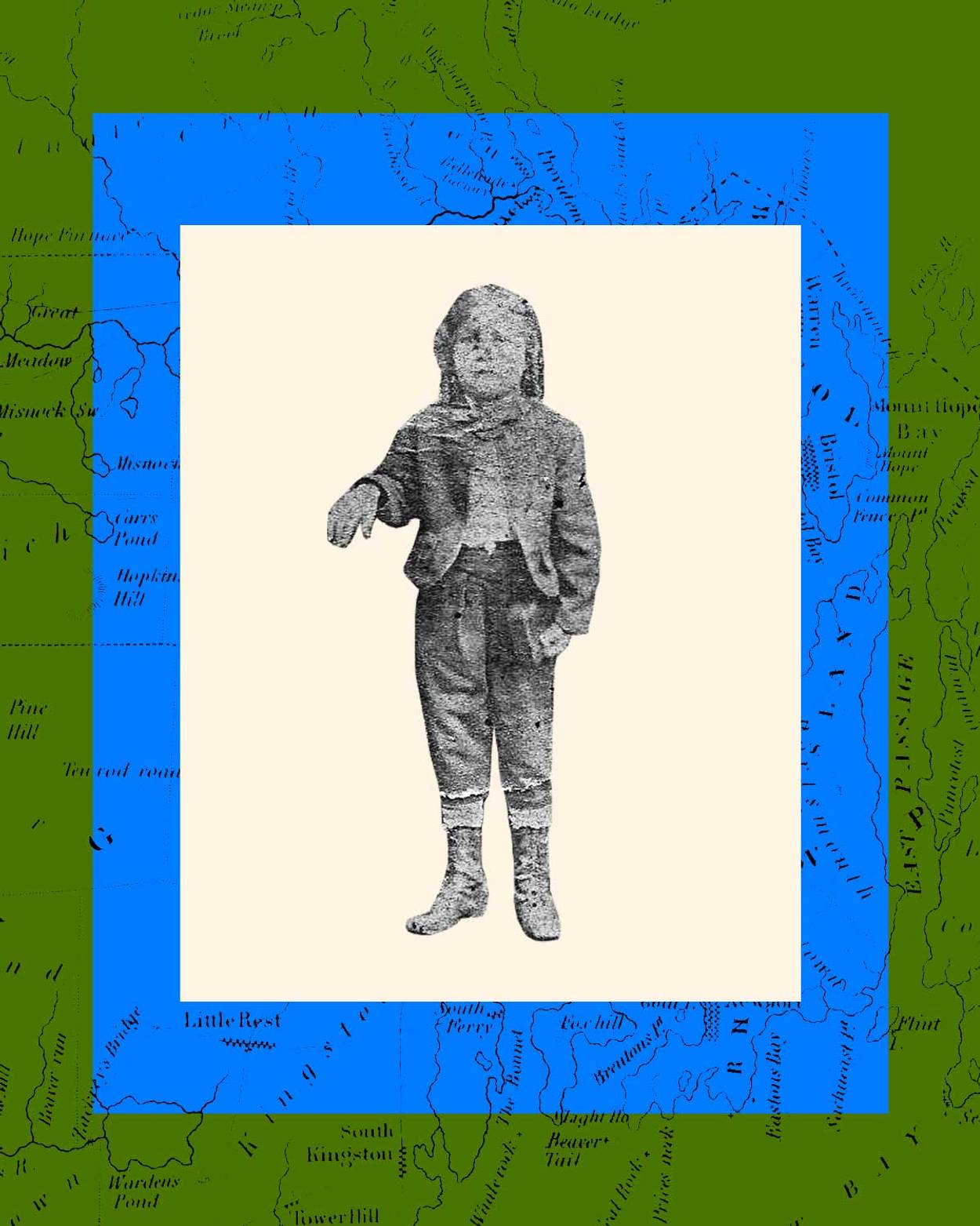

Richard Gustavus Forrester, the mixed-race son, was raised by his aunts Catherine and Slowey and went on, later in life, to become a distinguished citizen of Richmond. He was among the first African Americans to be elected to the City Council and was a founder of the Independent Order of St. Luke, which evolved into St. Luke’s Savings Bank. Whether or not Catherine and Slowey Hays were ahead of their time for having freely chosen not only to help raise their African American nephew but to assure his and his family’s future prosperity, their having done so sets them apart from the mass of slave-holding families, Jewish and gentile alike. Keith Stokes notes the uniqueness of the situation. When Slowey died in 1836, she bequeathed her entire estate to her sister Catherine and to Excy Gill. Other members of the Myers family were scandalized. Within the Myers clan, attitudes toward slavery and family loyalty varied widely. The Nat Turner Rebellion lay only five years in the past, after all. Those members of the Myers family who objected to Slowey’s and Catherine’s actions were angered by what Stokes refers to as the sisters’ “abolitionist principles.”

Slowey’s will, whose executor happened to be Gustavus Adolphus Myers, drew attention to two people in particular who, according to a more conventional view, would not have warranted it:

All and everything my sister Catherine must take as her own without reserve as I request of her, and if she should die when I do, I desire two thousand dollars may be presented to Excy Gill our faithful friend and servant. And that Richard, the son of Nelly may be purchased and his freedom given him, if his owner or owners consent with, fifty dollars yearly during his life.

Twenty years later, when Catherine died, her will made further provisions for Richard Gustavus Forrester. When he reached the age of 21, Richard would be eligible to gain his freedom with his owner’s consent. Catherine Hays left $1,000 for his eventual use.

The story didn’t end there. When Excy Gill died in a fire in 1855, she bequeathed her slave Narcissa (Richard Forrester’s wife) to the Hays sisters’ cousins, Catherine, Harriet, and Julia Myers. Excy Gill also emancipated all nine of Narcissa’s children, including Keith Stokes’ great-grandfather Richard Gill Forrester. Stokes is aware and grateful for the acts of Slowey, Catherine, and Excy. They “had to overcome the prevailing myth of the natural inferiority of women,” as he put it, by directly controverting the repressive practices of their day. As a result of their actions, his family was “not only able to survive, but live and prosper in one of the most difficult times and places for persons of African heritage: antebellum era Richmond, Virginia.”

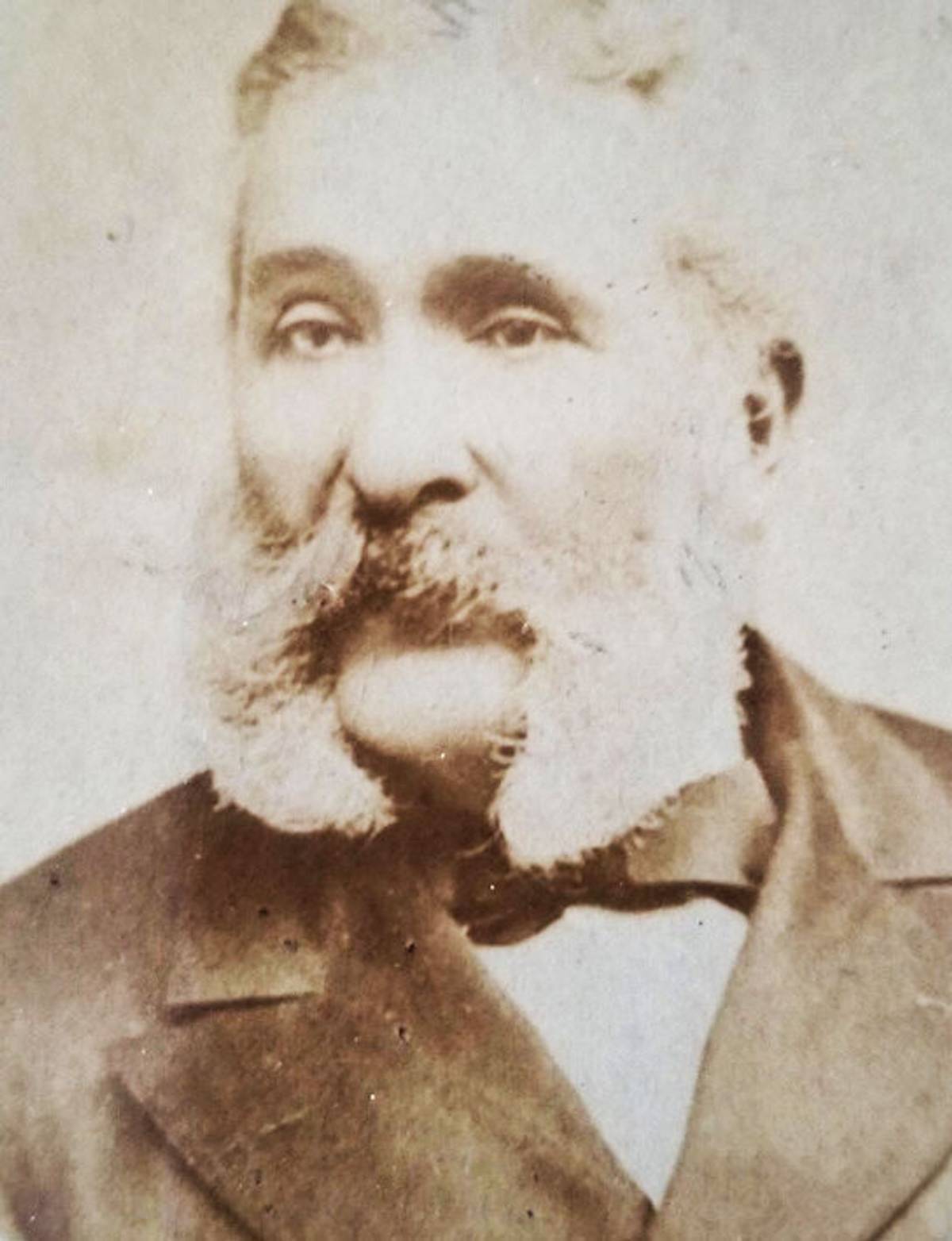

The legacy of the Hays and Touro families lived on, in other words, but in a milieu that was significantly different from what we might expect from descendants of Sephardic “Grandees.” Keith grew up in Newport, in the home that his identifiably African American grandparents had purchased after their “return” northward in the early decades of the 20th-century. The Forresters’ prosperity, he notes, began in Richmond. In the years leading up to and including the Civil War, Richard, making the most of his Jewish aunts’ and Excy Gill’s provisions for his future, established himself as a dairy farmer. At the war’s conclusion, his son Richard Gill Forrester, thanks in part to the loyalty he had shown to the Union cause, even during the years when the city served as the Confederacy’s capital, was recognized by the federal government and hired by the United States Post Office. Richard Gill Forrester eventually moved north, first to New York and eventually back (during the summers) to his aunts’ home city of Newport. Richard Gill Forrester’s daughter, Keith’s grandmother, was born in 1882, the youngest of four sisters who, as he tells it, made the most of their relative financial advantages by amassing educational achievements, participating widely in civic and religious life (as Episcopalians, eventually), and dividing their time between a home that they owned on 134th Street in Harlem (near Strivers’ Row) and the vacation haunts of Newport.

As Keith tells it, the Hays, Touro, and Gill legacies, as they had been passed onto Richard Gill Forrester, sparked a difference in the lives and choices that his family members have made ever since. “We’ve done well today,” he says, “because we’ve worked for it and we’ve earned it.” From an early age, he was well aware that “not lots of Black folks were still going to college, whereas my grandfather did, my grandmothers did, my mom did, my brothers who were older than me were going to college and working on master’s degrees.” The family had “opportunities and choices that most other people didn’t have.” A foundation of financial security allowed for a legacy of intergenerational prosperity and, besides that, a sense of belonging and a oneness with place. Keith grew up in the Newport home that his grandparents had purchased in 1917. After attending Cornell and the University of Chicago, he returned to Rhode Island, where his Hays and Touro progenitors had first arrived in the 18th century and his grandfathers’ ancestors had been among “the earliest free Africans” in the town.

For Keith Stokes, the story of his great-grandfather Richard Gill Forrester holds a particular weight in the present. In the spring of 1861, as Virginia seceded from the Union, the young grandson of Nelly Forrester and Gustavus Adolphus Myers was serving as a page in the state capitol. As the Union flag was lowered in order to accommodate the raising of the Confederate standard, Richard rescued the discarded flag from a trash heap and hid it under his bedding, where he kept it safe through four years of war. In April of 1865, in the midst of “all the fire, smoke, and confusion” that preceded the Union Army’s entry into the Confederate capital, Richard found a way to raise the flag he had kept hidden in his bed to the top of the flagpole that stood on the roof of the Confederate capitol. An officer from the 13th New Hampshire regiment who saw the flag go up was pleased to meet the “light-colored boy named Richard G. Forrester” who had acted for the honor of the Union.

The June 2020 post in which Keith Stokes tells this story highlights its thematic convergence with “the most tumultuous times” of our own historical era. His ancestors, who were “of African, Jewish, Christian, and mixed racial heritage,” he writes, “believed that, while not perfect, our country still held the opportunity for them to be recognized as full citizens.” Though this story takes place against the backdrop of the Civil War, before the adoption of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments resolved the question of slavery, it can’t help but alert us to the nation’s ongoing legacy of racial strife, as well its periodic bouts of redemption and reconciliation.

Reckoning with the past can wreak a sort of havoc in the present. I learned this lesson as I made the acquaintance of three of Keith Stokes’ Richmond-based white relatives. Keith had only recently met his Virginia cousins, Drury and Armistead Wellford, as a result of their mutual interest in their early American Jewish genealogy. The Wellfords (they are sister and brother) grew up in Richmond in the 1960s and 1970s. It was their cousin Ann Preston, who they both recall having been their primary guide to family history. “Growing up,” Drury explained, “we heard the names Hays, Touro, Myers, and Mordecai—all the time.” Notwithstanding the family’s comfortable immersion in the elite world of white, Episcopal Richmond, Drury and Armistead “were told specifically” that their generation was “one-sixteenth Jewish.” For whatever reason, “the family was very proud and remains very proud” of its Jewish heritage. In 1913, Caroline Cohen, another aunt, had penned a genealogical account which made the rounds of extended family members and, in the process, inscribed itself into Drury’s memory. Along with the copy of Stephen Birmingham’s The Grandees that Drury’s daughter Rosie Loughran recalls having seen prominently displayed during her childhood, such recognition lent color and excitement to family life.

I asked Drury and Armistead to tell me how they first became acquainted with their Rhode Island cousin, Keith Stokes, after several generations of mutual ignorance of one another had passed. “It’s not a very nice story,” Drury told me as she addressed the history of her own family’s reluctance to reckon fully with its past. As Armistead went on to recount, their cousin drew their attention to an article in the historical magazine The Virginia Cavalcade about Richard Gustavus Forrester. The article explained how Forrester’s father, Gustavus Myers, had arranged for his grandson, Richard Gill Forrester, to be employed as a page in the Virginia capitol before the Civil War broke out. It went on to tell the story that Keith Stokes tells, about the April 1865 flag-raising. The cousin wanted Drury and Armistead to be troubled by what they read. After all, it referred not only to their Jewish roots through the Myers family but to their African American relatives. “I don’t think she expected me to be so thrilled,” Drury says.

Caroline Cohen, the Wellford’s aunt, said nothing in her 1913 family history about any biological connection between the white (and Jewish) members of the family and the relatives whose point of origin had been Gustavus Myer’s relationship with Nelly Forrester. The book “never says that we’re related,” Drury notes, but instead notes in passing that Richard Gustavus Forrester had been a handsome man who, along with his mother, had first been purchased by the Hays sisters and then, later in life, went on to become their heir. It wasn’t until the Wellfords read the Virginia Cavalcade article that they put two and two together and made contact with Keith. At the time, Drury was working as the photo-archivist at the Museum of the Confederacy. In her attempt to find a photograph of Richard Gustavus Forrester, she landed on Keith Stokes’ website. It took a few years before the two made actual contact. Eventually, Drury introduced herself to Keith Stokes on Facebook: “Hey,” she wrote, “I’m your cousin.”

The question, as Drury’s brother Armistead frames it, is “Why the hell doesn’t everybody in Richmond know about Richard Forrester?” It’s hardly a mystery that Richard Gustavus Forrester’s and Richard Gill Forrester’s stories fail to jibe with the “lost cause” heritage that, until a decade or so ago, formed the foundation of many white Richmonders’ sense of their own history. What is at least slightly surprising, as Armistead notes, is that when Keith Stokes sought to publicize these stories, the director of the city’s African American history museum told him (Stokes) that “nobody [was] ready for that narrative” because Richard Gustavus Forrester’s primary claim to local fame had been his enormous wealth. When the facts of history don’t comport with our needs and expectations in the present, which happens quite often, we can’t help but find ourselves at a loss.

While there is no denying DNA, and while the past, as Faulkner and others have reminded us, “isn’t even past,” the shape that it assumes in the present is, like the proverbial elephant being described by touch and feel, is itself a fictional device that is, ultimately, the product of an entirely subjective experience that we create today. Like so many other pastimes that explore history in order to shape and give meaning to our current lives, genealogy generates its truths in the realm of the here and now. It can only answer the questions that we put to it in a language of its own fashioning.

Michael Hoberman is a Professor of English and American Studies at Fitchburg State University and author of A Hundred Acres of America: The Geography of Jewish American Literary History.