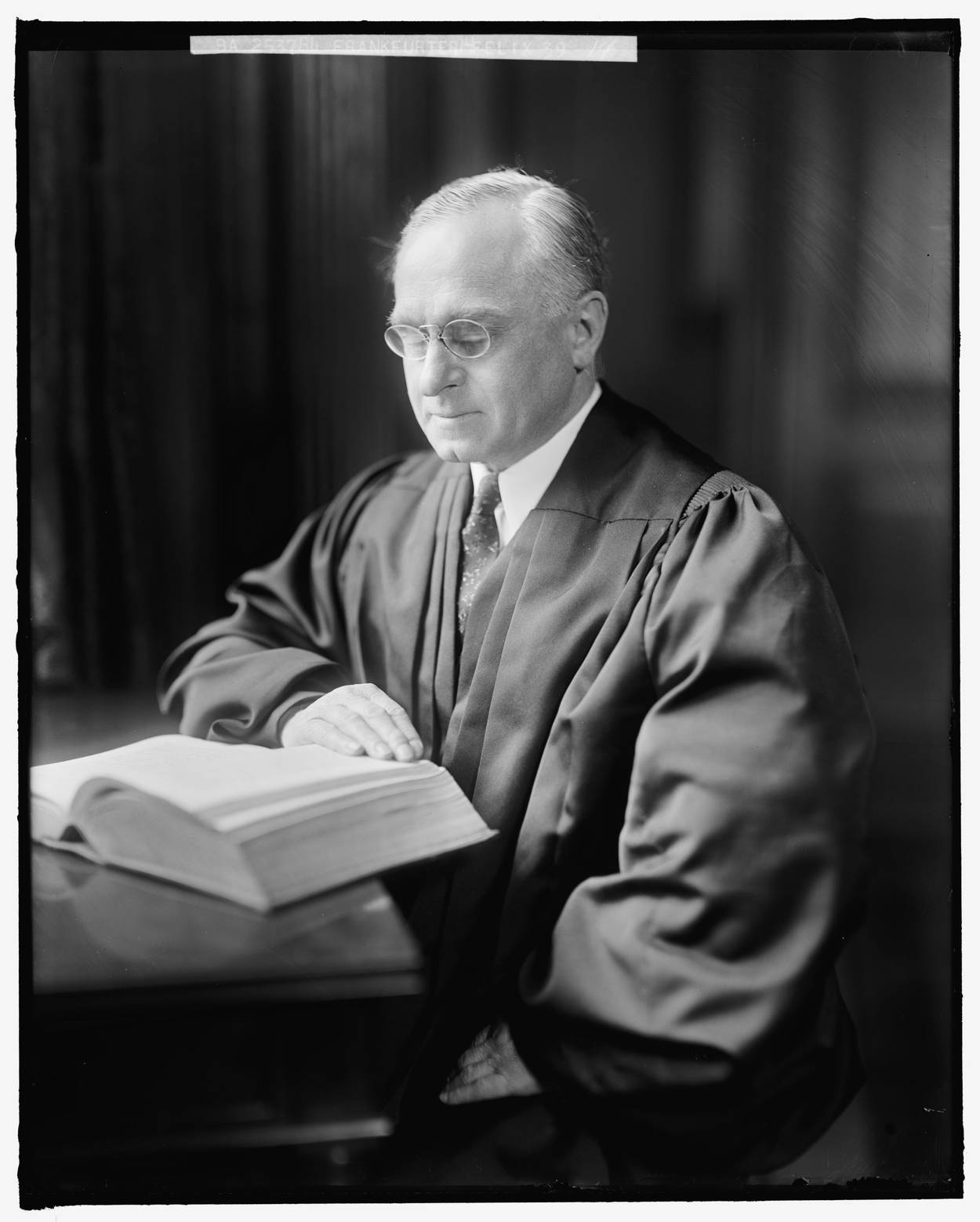

From Jew to Judge

Felix Frankfurter’s journey to the Supreme Court meant trading his Judaism for the “true democratic faith”

When Franklin Roosevelt nominated Felix Frankfurter to the Supreme Court in 1939, it marked the first and only time in U.S. history that a president conferred that honor on a Jew of foreign birth. For millions of Jews whose families had fled persecution overseas, Frankfurter’s ascension to the high court offered a powerful symbol of America’s promise. But the seminal role that Frankfurter enjoys in American Jewish history is riddled with irony: He shed his yarmulke long before donning his judicial robes. Frankfurter’s journey—not as a Jewish judge, but from Jew to judge—nods to a larger truth: Jews on the Supreme Court have shouldered burdens unknown to their Christian colleagues.

Felix Frankfurter was born in 1882 into an Austrian family that had produced generations of rabbis dating back centuries. When he was on the cusp of his teenage years, his father took a solo trip to the United States and “fell in love with the country, and particularly with the spirit of freedom that was in the air,” Felix later recounted. The father decided that he would send for the rest of his family to join him stateside permanently. Within a year, the Frankfurters had uprooted from their homeland and relocated to the humming metropolis of New York City. “From the moment we landed on Manhattan,” Felix recalled, “I knew, with the sure instinct of a child, that this was my native spiritual home.” The sublimation of Frankfurter’s religious identity into a civic one had already begun.

Despite his upbringing in an observant Jewish household, he withdrew from religious practices in a singular moment of clarity. Frankfurter was attending a Yom Kippur service as an undergraduate when he abruptly sensed his indifference to its rituals. “I looked around as pious Jews were beating their breasts with intensity of feeling and anguishing sincerity”—he was referring here to the Jewish practice of tapping one’s chest in repentance—“and I remember with the greatest vividness thinking that it was unfair of me, a kind of desecration for me to be in the room with these people … adhering to a creed that meant something to my parents but ceased to have meaning for me.”

Frankfurter suddenly exited the synagogue and never again resurfaced at a Jewish service. For the remainder of his life, he still identified as a Jew—and understandably so, as Jewish identity entails more than theological commitments—but his relationship with Judaism as a faith had met a swift demise. Frankfurter came instead to embrace a new religion: American democracy.

He became an apostle of the “true democratic faith” and routinely described the American legal system in decidedly religious terms. “Society has breathed into law the breath of life and made it a living, serving soul,” Frankfurter wrote in language mirroring the Book of Genesis’ description of how God animated Adam with breath. The U.S. Constitution, he suggested, was “Delphic,” an allusion to the Temple of Apollo’s high priestess. Frankfurter extolled legislatures as the heart of representative democracy and lauded them for exercising “prophetic judgment.” Harvard Law, where he enrolled at the age of 20 in 1903, was in effect his house of worship; he acknowledged having “a quasi-religious feeling about the Harvard Law School.”

The circumstances leading to his matriculation at Harvard must have seemed an exercise in divine predestination for the young Frankfurter. He initially intended to enroll at Columbia Law, but just when he was on his way to the campus to register, he encountered a friend who convinced him that the weather was too fine that day not to enjoy it outside. Enrollment could wait; Coney Island could not. Although Frankfurter had only intended to postpone his registration by a day, he then came down with the flu and did not make it uptown to Columbia. His doctor ordered him to leave New York City for the sake of his health—so Frankfurter absconded to Cambridge.

If democracy was his faith, the Constitution his scripture, and Harvard Law his temple, then Frankfurter’s prophet was James Bradley Thayer. In 1893, Thayer had published an iconic essay in the Harvard Law Review arguing for judicial deference to legislatures. Frankfurter described Thayer’s publication as “the compelling motive behind my Constitutional views … the Alpha and Omega.” Here he invoked the two Greek letters that refer to God in the Book of Revelation. To be sure, there were other prophets in Frankfurter’s civic faith—but even these prophets were disciples of Professor Thayer. As Frankfurter, near the end of his life, told the historian Arthur Schlesinger, “Both Holmes and [Louis] Brandeis influenced me in my Constitutional outlook, but both of them derived theirs from the same source which I derived mine, namely, James Bradley Thayer.”

Given Frankfurter’s profound reverence for Thayer, it is a striking fact that the two never met. When Frankfurter arrived in Cambridge to begin his legal coursework, the Harvard professor of legend had passed away just the year prior. Frankfurter spent the remainder of his years lamenting that he had narrowly missed the opportunity to learn from Thayer directly. “That James Bradley Thayer was no more when my class entered the School has been a lifelong bereavement for at least one member of that class,” Frankfurter remarked nearly four decades after his graduation. Even 60 years following Frankfurter’s law student days, he was still recalling how often he had been told by others “that I came too late to the School to encounter the mind I would have found most congenial to mine, that of James Bradley Thayer; and I am sure [this] was right, judging by everything I have heard of Thayer and everything of his I have seen in print.”

Thayer was gone, but his memory still permeated the law school while Frankfurter was earning his degree. In a speech that Frankfurter delivered late in life at Harvard Law, he exalted “the traditions of James Bradley Thayer, echoes of whom were still resounding in this very building in my student days.” Frankfurter’s failure to encounter Thayer in the flesh appears to have only strengthened his affection for the deceased scholar. Unencumbered by the foibles that come with actual personal familiarity, Frankfurter had it all the easier to turn Thayer into an idol. And by infusing Thayer’s memory with a sacred quality, Frankfurter bolstered his own stature as heir to a righteous lineage.

Frankfurter was strikingly self-aware that the absence of Judaism in his life informed his jurisprudence. He told his fellow Supreme Court justices, “As one who has no ties with any formal religion, perhaps the feelings that underlie religious forms for me run into intensification of my feelings about American citizenship.” Coming of age at a time when antisemitism had real purchase, perhaps Frankfurter felt, even subconsciously, that he could not be both fully Jewish and fully American, so he rejected the former for the latter.

To be sure, not all Jewish judges in the United States feel compelled to run from their faith. But Frankfurter’s story is not wholly anomalous. Most Supreme Court Justices of Jewish identity untethered themselves, in varying degrees, from an observant Jewish heritage—from Arthur Goldberg to Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Abe Fortas, a Lyndon B. Johnson appointee to the high court, forthrightly described his parents’ Judaism as “an obstacle to overcome, rather than as a heritage to be celebrated.” It is difficult to imagine the likes of Antonin Scalia or Amy Coney Barrett describing their Catholicism in such terms. If a certain degree of religiosity in a Jewish judge remains a tacit barrier to membership on the high court, then the egalitarian promise discerned in Frankfurter’s nomination remains not yet fully realized.

This piece is adapted from Porwancher and Jipp’s coauthored book, The Prophet of Harvard Law (University Press of Kansas, 2022)

Andrew Porwancher is the Wick Cary Professor of Constitutional Studies at the University of Oklahoma.

Taylor Jipp lives and works in London as a research and writing consultant.