Are Jews Black?

Black History Month: A brief history of an often-pernicious and persistent question of race

How things change! The current debate about the idea put forward by Marc Dollinger in the new introduction to his Black Power, Jewish Politics, that there are elements of “white supremacy” in the lived experience of American Jews, has left me bemused. The notion that Jews, of all people, are now being labeled as significant historical beneficiaries of “white privilege” seems a curious turnabout.

For hundreds of years in Europe there were horribly influential strands of belief that insisted that Jews were somatically as well as metaphorically Black. The discovery of actual Black Jews during the period of the Enlightenment confirmed the association Jews were thought to have with Blacks. Racist anthropology throughout the 19th century and early 20th centuries and during the period of Nazi domination of Europe sought to demonstrate that Jews had Black skin, Black blood, and Black origins. So where does this new controversy come from?

The ironic redefinition of the “color” of Jews is being played out in America within the context of the growth of Black Jewish groups in the United States and the further propagation of the idea that all Blacks are descended from the ancient Israelites. Some of these groups doubt the credentials of white Jews, while others resent their exclusion from the Jewish mainstream on grounds of color. This issue came to wider public attention in part as a result of the chance intersection in January 2019 of one very particular subgroup of Black Jews—the Black Hebrew Israelites; some participants in the Indigenous People’s March; and a group of pro-life Catholic high school boys from Kentucky, in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. The Black Hebrew Israelites merrily saluted the Native Americans as descendants of the Lost Tribes of Israel, cursed the schoolboys as white “Edomites,” and found themselves on the TV sets of anyone in the United States who happened to tune in to the day’s news.

Black Jews in America—one very particular subgroup thereof—thus became visible as never before, which helped lead in part to the color of Jews and the meaning and implications of that color becoming once again a matter of wider debate, joined by everyone from religious communities outside the American Jewish mainstream, to a new generation of racial ideologues, to the children of “mixed” marriages between African American and Ashkenzai Jewish partners, to well-meaning young people eager to engage in the now-fashionable calculus of racial typologies and assumed racial deficits and virtues.

To understand what an astonishing development this is, we have to return to the history of Jewish color. For several decades the study of Black Jews in different parts of the world has been one of my major academic preoccupations. My first encounter with Black Jews came in the fall of 1984 when I was asked by the Minority Rights Group to go to the Sudan and write a report on the situation of the Beta Israel—Ethiopian Jews—in the refugee camps strung along the border with Ethiopia. Ethiopians had been streaming into Sudan on account of political turmoil and famine for years. Rumor had it that the Ethiopian Jews, who were dying in shockingly large numbers, were being poisoned by Christian refugees. My job was to report on this dreadful situation.

Having arrived in Gedaref, a scruffy Sudanese border town, it soon became clear to me that something terrible was indeed going on. The first thing I saw was a Jewish cemetery with thousands of recent makeshift graves. Jews were indeed dying at a terrifying rate. A couple of days later I heard Hebrew being spoken in the refugee camps by people who looked like aid workers but were equipped with walkie-talkies and army boots.

One day I met an official with an international aid organization. I revealed to him what I had seen and he revealed to me that he was coordinating an operation with Mossad that would take the Beta Israel covertly to Israel. He swore me to secrecy and promised that when the time came, he would personally let me know the background to the Israeli initiative, which would eventually be known to the world as Operation Moses. A couple of days after the operation was blown by an Israeli news outlet, the official flew from Israel to London and did as he had promised. I went on to write the first book on the operation.

Some months later I was invited to go to South Africa to give a talk on the Israeli operation and on the Beta Israel. My audience was a relatively affluent white South African Jewish group but at the back of the hall I noticed a number of Black men wearing yarmulkes. After the talk they explained with some hesitation that they were of the Lemba tribe and that they were related to the Ethiopian Jews. They had come, they claimed, to Africa from the Middle East, millennia ago.

At the time I was a professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, and knew something about Jewish history. I had never heard of any historical Jewish group in central Africa. The only Jewish group I knew of were the Ethiopian Jews: And even their origins, at the time, were hotly contested in the scholarly world.

Spending some time in Lemba villages on the border with Zimbabwe I became convinced that there was something vividly Semitic about this Bantu tribe and something irresistible about their oral traditions, which painted a picture of a migration from a mysterious town called Sena centuries before. I decided to make a road map of their oral tradition and follow it from village to village, from kraal to kraal, across the African continent.

The resulting book, Journey to the Vanished City, described the attempt to recover the lost history of a people. However, it was only with the advent of accessible DNA testing that a window into this obscured past was finally found, one that seemed to confirm the oral tradition of the Lemba, that they were of Jewish origin. This project would also contribute a complicating strand to the vexed question of who is a Jew.

Both in the case of the Ethiopian Jews and the Lemba I was astonished by the interest shown by the international media in the question of Black Jews. It seemed to challenge Western ideas about what Jews were supposed to be like. I presented a number of TV documentaries; a section of 60 Minutes covered my work and hundreds of articles in the world’s press were devoted to the topic. Insofar as much of the new problem hinged on the role genetics played in the identity of Black Jews (a development that was eagerly seized upon by aspiring Black Jews throughout the Americas and Africa), this seemed to be a very modern development.

However, a few years ago when I was reading an obscure 18th-century German book I suddenly realized that our current interest in the color of Jews was not new at all. The missionary author of this German tome had noted that a slave from the tiny west African kingdom of Loango had mentioned that in his homeland there were Black Jews “who celebrate the Sabbath so stringently that they do not speak a word all day … their graves are made of masonry and adorned with figures of serpents and lizards painted on by those who come to bury the corpse.”

A couple of years before, I had written a book based on the Huggins lectures I had given at Harvard University. The book was a history of the many African groups that claimed Jewish descent. However, in my book, Black Jews in Africa and the Americas, I had made no mention of the intriguing community of Loango, whose existence somehow I had missed. It was galling.

Piqued, I started following stray leads and to my astonishment discovered that the scholars of the European Enlightenment (including some early Jewish maskilim) knew all about this community. Indeed, the Black Jews of Loango—and other Black Jews in India, the Sahara, and Ethiopia—were a fundamental and critical building block in the onward construction of the concept of race both in Europe and the United States.

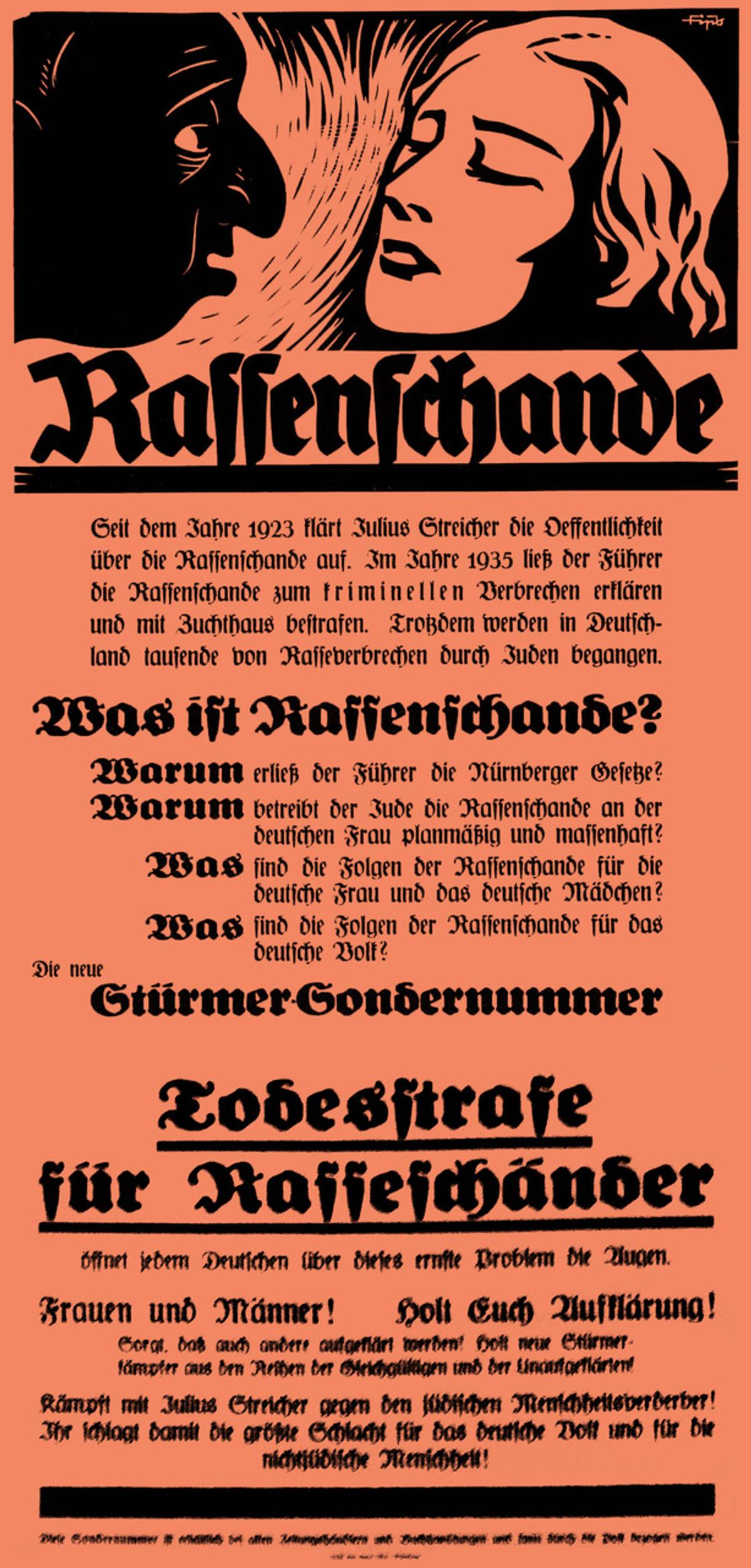

From the middle of the 19th century until the Nazi period, the idea that Jews were multicolored played into the burgeoning idea that if you looked hard enough all Jews were actually Black. They were Black in the sense that they had Black blood—and they were also Black in the most literal sense that their skin was black, even if you could be lulled into thinking it was kind of white. In my book Hybrid Hate: Conflations of Antisemitism and Anti-Black Racism from the Renaissance to the Third Reich, I examine assumptions about Jewish color for hundreds of years, which culminated in the absolute and foundational Nazi conviction that Jews were “Negroid.”

The color of skin was a minutely studied subject in the 19th century. One of the greatest authorities on pigmentation was the Englishman John Beddoe. He had served with distinction in the Crimean War in the British field hospital made famous by Florence Nightingale, and while he was there did a physical anthropological study of the skins of the multinational population incarcerated in the hospitals of the Dardanelles. He subsequently went on to analyze the eye and hair colors of the peoples of Europe and thereby laid the foundation of the great pigmentation surveys, which would be carried out in Germany and elsewhere in Europe in the last decades of the 19th century.

One of Beddoe’s achievements was to create a meticulously annotated “index of nigrescence” of the population of Great Britain. Jews scored fully 100% on his “nigrescence” index.

An even larger pigmentation study, which involved nearly 7 million schoolchildren, was carried out in Germany, shortly after German unification in 1871, by the distinguished German scientist Rudolf Virchow. The teachers were provided with a set of instructions that required the children to stand in line with the blondest-haired children at one end and the darkest haired at the other, in a continuum of hair color. This way the children learned that there was a hierarchy of color.

In the Virchow study, skin color was “shown” to be a function not only of what was visible, but also of the relationship between hair and eye color. Visible skin color was in fact of no importance for the study. Children were asked to roll up their sleeves to reveal the true color of their arm. In other words, the skin color that you could see with your naked eye was not necessarily the real skin color of the individual (for that you would have to have some specialized knowledge and partially undress him/her) and there were “scientific” ways of determining what skin color actually was.

This fascination with Jewish color came at precisely the point at which emancipation had finally come to the Jews of the Reich. However, it was also the point when the hatred of Jews was being increasingly expressed in not social, religious, or economic, but in racial terms, one of the catalysts for this development being Wilhelm Marr, who in 1879 introduced the term anti-Semitism into the world’s political lexicon.

Marr had started his political life as an anarchist. He had no particularly anti-Jewish views and in fact had three Jewish wives, one of whom he loved to distraction. It was during an extended trip to North America that Marr learned how to be a racist. He’d seen slavery of Black people in action and wholeheartedly approved of it. He loathed Black people, and soon transferred his contempt for Blacks wholesale to Jews.

Filled with the views of the racist physical anthropologists of the time such as the Scottish physician Robert Knox or Joseph Arthur Gobineau, the French aristocrat who helped develop the theory of the Aryan master race, Marr argued that the blood of the Negro flowed freely in the veins of Jews. Jews therefore really were somatically as well as metaphorically the Blacks of Europe. What the Americans did to Blacks, Marr advocated, Europeans should now do to Europe’s own Blacks—the Jews.

Even before the rise of Nazism, Marr’s equation of Jews and Blacks started to fill the media of the time. Theodor Fritsch, the publisher of the anti-Semitic German magazine Hammer, explained that Jews’ loathsome characteristics could only be explained through their African ancestry. The acclaimed French novelist and Holocaust denier Louis-Ferdinand Céline considered Jews to be entirely African: “le Juif est un nègre—la race sémite n’existe pas” (the Jew is a Negro—the Semitic race does not exist).

Nazi and Fascist race theorists embraced these ideas enthusiastically. There was a broad consensus among Nazi, Vichy French and Italian Fascist anthropologists that there were marked Negroid elements in Jews. These ideas were also present in the United States: The Ku Klux Klan regularly lumped Blacks and Jews together, as did many homegrown American race theorists. In 1910, Dr. Arthur Talmage Abernethy—the author of some 50 books—published The Jew a Negro, in which he stated categorically that “the Jew of today, as well as his ancestors in other times, is the kinsman and descendant of the Negro.”

Much of the inspiration for the discriminatory legal codes enacted against Jews, Blacks, and others by the Nazis came from the Jim Crow laws. However, the main problem with American racial legislation from a Nazi perspective, was that Americans did not formally include Jews in the category of “coloreds.” But in 1934 Roland Freisler, later the presiding judge of the Nazi People’s Court, noted that that this omission didn’t really matter: The American legislation could be used without much modification because, as he put it, “any judge would place the Jews along with the coloreds, even though they look outwardly white.”

Hitler argued that Germany had been deliberately “negrified” by the Jews whose intent was to weaken and destroy German society through racial contamination. In Mein Kampf he wrote of the Jews: “Systematically these Negroid parasites in our national body corrupt our innocent fair-haired girls and thus destroy something that can no longer be replaced in the world.”

As Jews today confront charges of white privilege and lament the deteriorating relationship between African Americans and American Jews since the glory days of Jewish participation in the struggle for civil rights, both groups might dwell for a moment on the thought that the color of Jews and Blacks has only recently been uncoupled. The hatred of Jews and the hatred of Blacks have a common origin. It is indeed a hybrid hate.

Tudor Parfitt is a British historian. He is Distinguished University Professor at Florida International University and Emeritus Professor of Modern Jewish Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London University. He is the author, most recently, of Hybrid Hate: Conflations of Anti-Black Racism and Anti-Semitism from the Renaissance to the Third Reich.