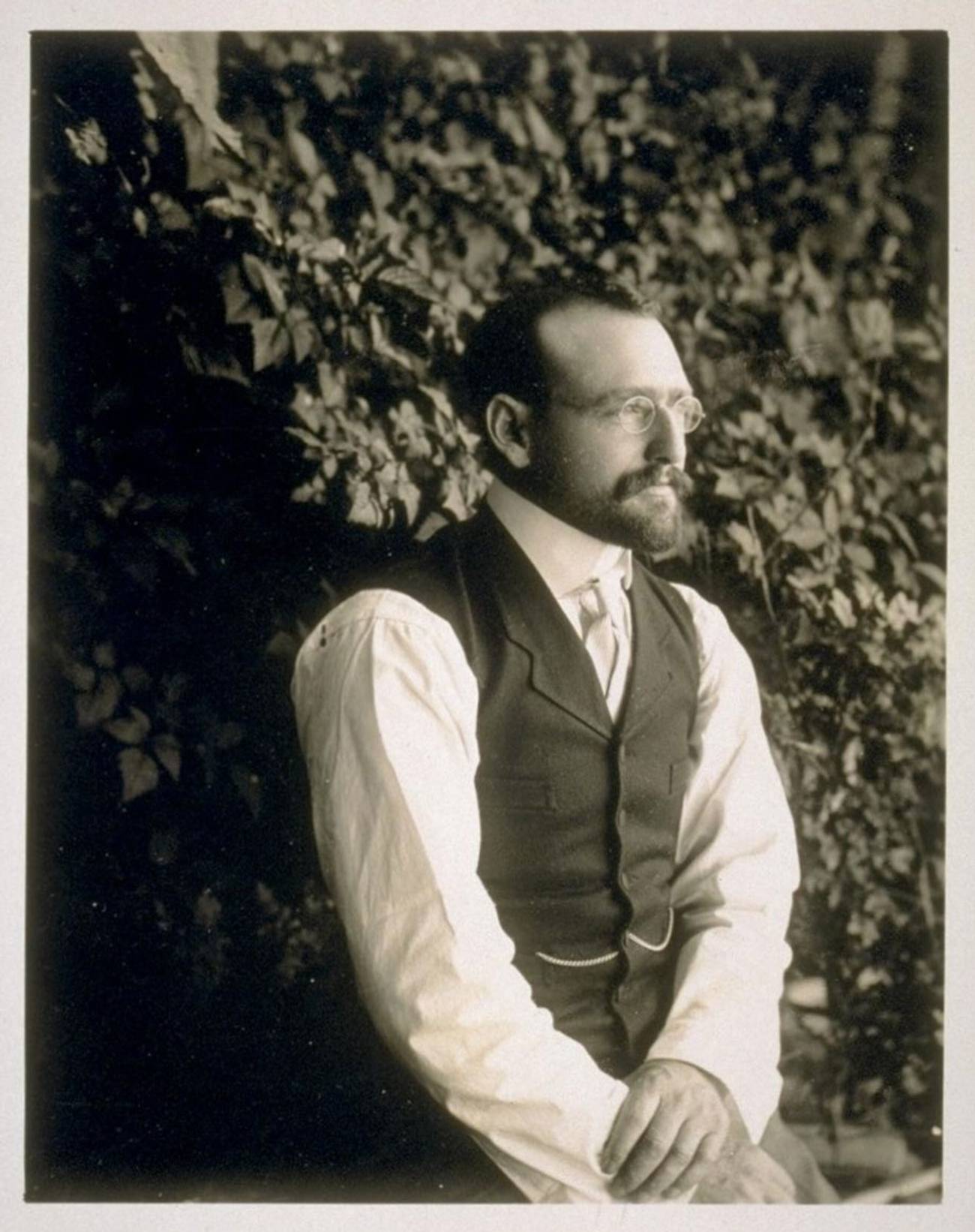

On July 12, 1895, Theodore Seixas Solomons and his friend Ernest Bonner left Jackass Meadows, a camp 100 miles northeast of Fresno, for an exploratory excursion through California’s Sierra Nevada range. The two men wore felt hats, layered wool shirts, and “shoes with slightly projecting hob-nailed soles.” Their canvas backpacks brimmed with the latest innovations in outdoor equipment: eider down quilts that each weighed four pounds, kola nuts (for headache relief), extra buckskin straps, and 60 pounds’ worth of “ham, canned salmon and corned-beef, flour, white corn-meal, oatmeal, and hominy.” As Solomons recounted a few months later, they were on their way to an area that had been “represented on the map by blank spaces drawn in such a way as to indicate that the topography thus indicated was mythical.”

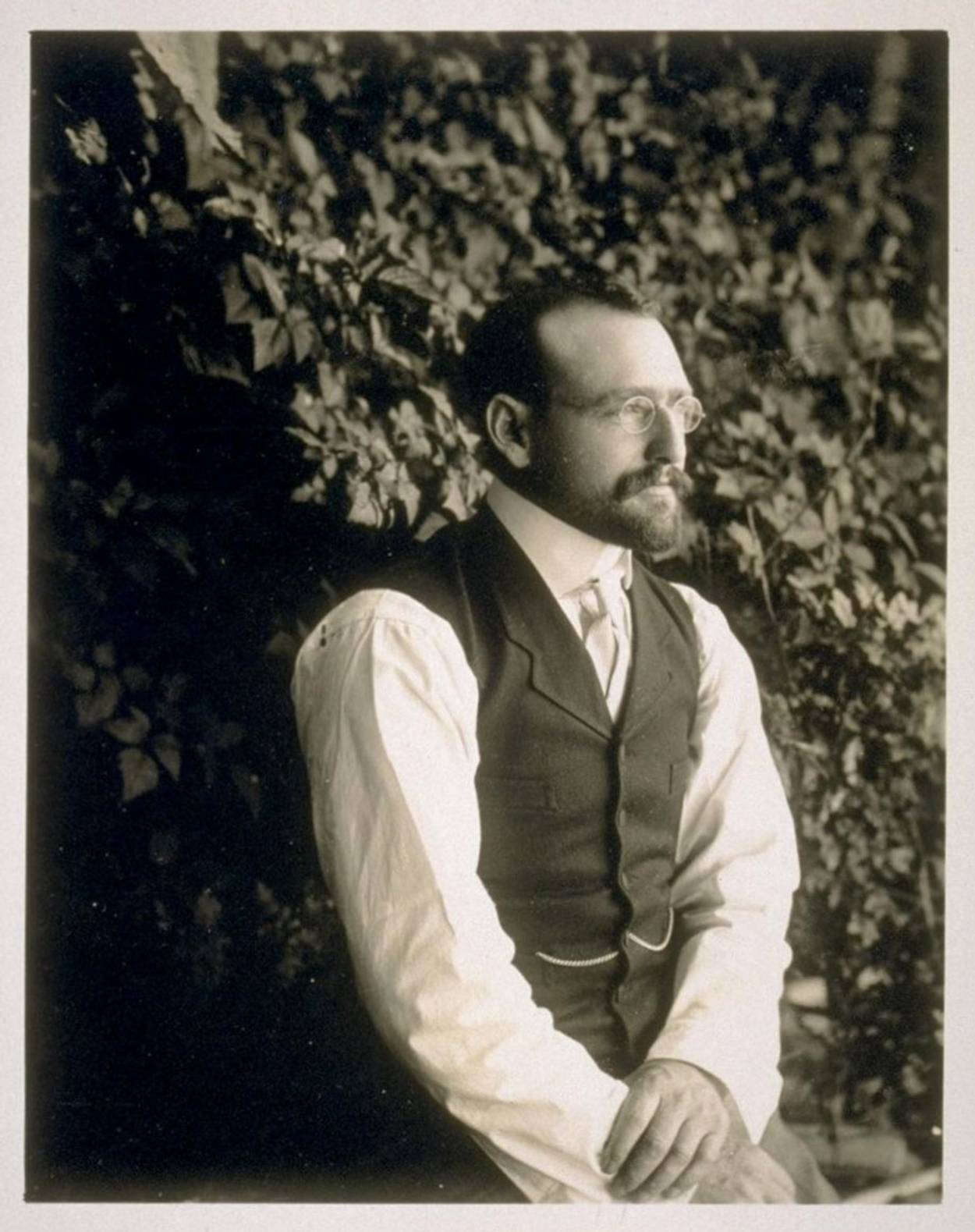

Over two weeks of hiking through this territory would lead Solomons and Bonner to the brink of solving one of the greatest mysteries of “the Californian Alps”: how to traverse the middle portions of the trackless alpine wilderness that lay between the Yosemite Valley and Mount Whitney. Yet in 1915, when California officials finally commissioned the footpath that Solomons envisioned, they chose to instead name it in honor of the Scottish-born conservationist hero and Sierra Club founder John Muir. It was Theodore Solomons, however, a fifth-generation Jewish American, who first conceived of the trail and navigated its most challenging sections. Solomons’ role in the development of the John Muir Trail has long been overshadowed by the legacy of its namesake. In 1983, Ansel Adams owned that the explorer’s Jewishness may have factored into this result. Solomons’ role in the shaping of the nation’s best-loved and most spectacular long-distance footpath reminds us of the close, if often disregarded, bonds that Jews have formed with the North American wilderness.

Bonner & Solomons, King’s River Canyon, Sierra Nevada photographs / Taken by Theodore Seixas SolomonsBANC PIC 1971.061: 60, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Theodore Seixas Solomons was the only member of his storied family to follow mountaineering as a lifelong avocation, but he was not its first pathbreaker. In August of 1776, his great-great-grandfather, Gershom Mendes Seixas, the youthful hazan of New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel, earned a place in history through an unequivocal act of loyalty to the cause of the American Revolution. Refusing to swear the oath of allegiance to the Crown that would have been demanded of him had he remained in the city in the face of an imminent British invasion, Seixas led several congregation members who shared his affinity for the rebellion northward to Connecticut. In 1789, Seixas would be the lone Jewish clergyman (and probably lone Jew) in attendance at George Washington’s inauguration.

Three-quarters of a century later, in 1852, Theodore Solomon’s father, Gershom Mendes Seixas Solomons, traveled to and settled in California, at the height of the Gold Rush. He would become one of the founding members of San Francisco’s famed Temple Emanu-El. Theodore’s immediate family included one sister (Adele) who earned an M.D. from the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Boston and another (Selina) who led the suffragist movement in California.

Like his forebears, his intrepid siblings, and a host of other confident and adventurous young Jews loosed in the land of opportunity, Theodore Solomons knew what he was doing, even when he didn’t know exactly where he was going. Late in his life, Solomons recounted that the dream of walking the length of the High Sierra had first come to him in the summer of 1884 (a year after his bar mitzvah) while he was out “herding [his] uncle’s cattle in an immense unfenced alfalfa field.” In an essay that he published in the February 1940 edition of The Sierra Club Bulletin, he tried to recapture the moment in which it had come to him. “The Holsteins were quietly feeding,” he wrote, “and I sat on my unsaddled bronco facing east and gazing in utter fascination at the most beautiful and the most mysterious sight I had ever seen.” Mesmerized by the “flashing teeth of the Sierra crest,” Solomons projected himself eastward and upward: “I could see myself in the immensity of that uplifted world, an atom moving along just below the white, crawling from one to the other end of that horizon of high enchantment.”

Solomons’ role in the shaping of the nation’s best-loved and most spectacular long-distance footpath reminds us of the close, if often disregarded, bonds that Jews have formed with the North American wilderness.

When Solomons reached the age of 18, with no educational or career goal otherwise occupying or distracting him from his love of the mountains, he made his first trip to Lake Tahoe. His family was hardly thrilled at this fairly unconventional choice of pastime. By the early 1890s, however, his father had died, his siblings had already launched their careers, and his mother, Hannah Marks Solomons—she, too, was lineally connected to a storied early Jewish American clan—had made her peace with his quirky interests. While the family had once known and would eventually regain financial prominence, the period of Solomons’ early manhood coincided with a decadelong downturn in their fortunes. Theodore funded most of his youthful mountain ventures through extended stints as a court stenographer.

By the time that he and Ernest Bonner were preparing for their July 1895 expedition, Solomons had spent the better part of three summers hiking through (and, on a few occasions, barely surviving) the rigors of the Sierras. He had thoroughly explored Yosemite’s Tuolumne Valley and had also ventured southward from there to the lesser-known area surrounding Mount Ritter, Banner Peak, and the Minarets (all three mountains now comprise a large portion of the Ansel Adams Wilderness). He had bagged peaks, glissaded down glaciers, subsisted for days at a stretch on berries and mule meat, and been pre-hypothermic more times than he could count. On most of these trips, he, his friends, and his pack animals lugged a large camera, tripod, and several pounds’ worth of glass plates along with them. The archives at Berkeley’s Bancroft Library contain 250 of Solomons’ photographs of the Sierras, all of which he took between 1892 and 1896.

Solomons was also well acquainted with the Sierras’ most famous personalities. John Muir was a generous, if occasionally stern, mentor. Muir’s contributions to Solomons’ knowledge of the Sierras, however, were of a decidedly inspirational, as opposed to practical nature. In a 1935 article, Solomons described Muir as “exceedingly generous” and especially solicitous of “young mountaineers” like himself. At the same time, he judged Muir, “by the standards of the geographic world,” to be “a very poor sort of explorer.” Well past his youth, Muir had been fearless in his forays into the wilderness and indefatigable in his efforts to preserve it. While “he could aptly describe every place he had seen,” Solomons wrote, “you could seldom tell where it was, for he seldom oriented himself in his excursions.”

Solomons’ travel companions belonged to an eclectic group that included fellow Sierra pioneers “Little” Joe LeConte and Will Colby, as well as Leigh Bierce. On one memorable occasion he accompanied a group of four Cal-Berkeley “bloomer girls” on their ascent of Yosemite’s 13,000-foot Mount Lyell. The trip concluded with an exhilarating mile-a-minute glissade down a glacier that it had taken them several hours to climb.

On his first venture into the Sierras in 1892, Solomons’ companion was Sidney Peixotto, the scion of another clan of California Sephardim. The friend he chose to accompany him on his 1895 trip, Ernest Bonner, was a Berkeley law school associate of Solomons’ brother Leon. On his trips into the Sierra backcountry Solomons also regularly visited and consulted with the Portuguese and Basque sheepherders who brought their flocks to graze in its alpine meadows. His privileged childhood and adolescence in the San Francisco area could have ushered him into an easeful professional or business career. Instead of adhering to that path, Solomons cast his lot with people who shared his enthusiasm for and familiarity with the mountains.

The highest peaks of the Sierras rise where all of California’s principal rivers originate. When Solomons and Bonner left on their July 1895 adventure, their objective was to learn which watersheds connected the mountains that lie southeast of present-day Mammoth Lakes to the high peaks that dominate what is now Kings Canyon National Park. The men made their way southeast from Jackass Meadows, following the South Fork of the San Joaquin. They were hoping that their ascent to its headwaters would bring them to a height from which they could locate a pass into the Kings River drainage. They knew that future hikers could continue along that drainage all the way to Mount Whitney.

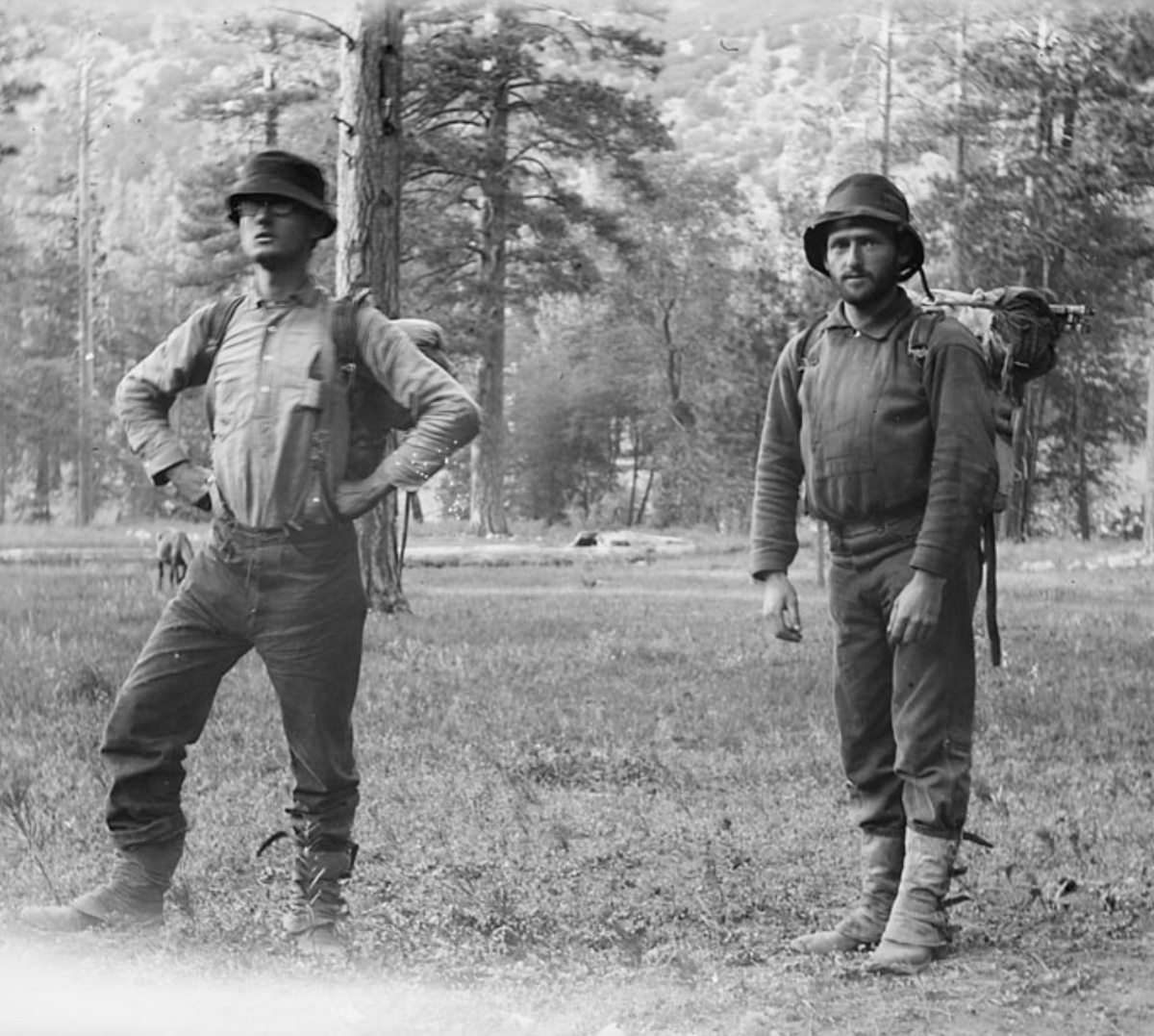

Sources of Middle Fork, San Joaquin River, Sierra Nevada photographs / Taken by Theodore Seixas Solomons, BANC PIC 1971.061: 39--NEG, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Solomons and Bonner came as close to locating the pass as anyone would in the succeeding dozen years, and had it not been for an early season snowstorm that drove them off the peak of 13,558-foot Mount Goddard on July 17, they would almost certainly have found it. In his 1896 report on the trip with Bonner, Solomons described the desperate situation whose onset prevented their triumph: “I had never passed a night at a higher altitude than this,” he wrote, “nor do I care to.” Huddled in the relative shelter of a tamarack grove, the two men managed to get a lifesaving fire going thanks to some “pitch saturated logs.” On the following day, trying their best to maintain the crest of the divide “in a blinding storm” for several hours, they held a course toward the still-hypothetical pass for as long as they could before seeking shelter in “a deep gorge that had captured [their] admiration and curiosity” the previous day from the steep slope of Mount Goddard. Before they made their descent, Solomons had formed as precise an idea of where the pass had to be as anyone could have. “From several heights,” he wrote in 1940, he “could see that at the head of the basin was an easily accessible gap or pass to the highest Middle Fork streams of Kings River.” On the map that he drew immediately following his 1895 trip with Bonner he went so far as to demarcate its approximate location.

Solomons’ and Bonner’s inability to cross over what is known as the Goddard Divide in the summer of 1895 was a temporary, if frustrating, setback to the development of the John Muir Trail. It was also one of several factors that seem to have cost Solomons the recognition he surely deserved—and had already more or less earned—for having been the path’s founder. “Had they not panicked,” speculated one late-20th-century Sierra mountaineer, Solomons and Bonner would most certainly have gotten to the pass. Thanks to Solomons’ thorough documentation of his 1895 trip, his friend and sometime hiking companion Joe LeConte managed to sight and then hike over the pass in 1908, thereby earning a place in the history books as the first person to travel the entire distance between Yosemite and the area around Mount Whitney. In the 1930s, trail builders erected Muir Hut, the only edifice that lies along the 212-mile length of the John Muir Trail, at the 11,980-foot summit of the pass.

‘I had never passed a night at a higher altitude than this,’ Solomons wrote, ‘nor do I care to.’

When Theodore Solomons died at the age of 79 in 1948, only a handful of his contemporaries acknowledged the role he had played in the trail’s creation. His 1940 Sierra Club Bulletin article had attempted to set the record straight by documenting everything from his 1884 gaze up at the Sierra crest from his uncle’s cattle farm, to his multiple trips through the 1890s (including the 1895 trip with Bonner) to his years of collaboration and correspondence with several other Sierra explorers. Solomons frankly admitted to the many setbacks he had faced along the way. During his lifetime, nothing that he had done or said earned him more than passing references in the Sierra Club’s official history of the trail’s development.

In 1965 veteran Air Force pilot, photographer, and Sierra Club member Hal Roth published a pictorial chronicle of the John Muir Trail called Pathway Through the Sky. The book included a chapter that summarized Solomons’ 1890s efforts to map out the trail. Two years later, the United States Geological Survey’s official designation of the 13,000-foot peak that hovers just to the south of Muir Pass as Mount Solomons helped to shore up the trail-maker’s legacy, at least among inquisitive map-readers. In 1974, Solomons was memorialized with a trail of his own, but even that act fell short of achieving its purpose of raising public consciousness about his contributions to wider knowledge of the High Sierra. The Theodore Solomons Trail is a rigorous 280-mile, lower-elevation alternative to the much more popular and well-known John Muir Trail. It receives comparatively little traffic, however, and, as a consequence, is often difficult to follow and inconsistently maintained. As one 2019 hiker put it, “If my experience is anything to go off of, almost no one knows about the bloody thing.” The same blogger claimed that when he called the Forest Service to request a hiking permit, he was told that they issue about three a year, as compared to the 1,500 or so that they provide to John Muir Trail hikers. To this day the story of the better-known trail’s Jewish pioneer remains mostly unknown, even to the hundreds of backpackers who complete its length each summer. For my part, when I hiked the length of the JMT in the summer of 2021, I had no idea that the path I was following had taken shape owing to the imaginative vision and daring physical acts of Gershom Mendes Seixas’ great-great grandson.

To this day the story of the better-known trail’s Jewish pioneer remains mostly unknown, even to the hundreds of backpackers who complete its length each summer.

Yet what Theodore Solomons experienced and found in 1895, besides eventually yielding the information that enabled Joe LeConte to find Muir Pass in 1908, itself merits retelling and commemoration. Well ahead of the freak July snowstorm that drove them off the side of Mount Goddard, he and his companion had already become the first recorded Sierra travelers to enter an area that, in an expression of his enthusiasm for the scientific developments of the day, Solomons decided to call the Evolution Basin. Two days out from Jackass Meadows, they found themselves ascending a steep tributary gorge of the South Fork San Joaquin that, as Solomons would write in his trail report of 1896, contained more water than its narrow volume seemed capable of holding. “Swelled by the fast-melting snows of its high sources,” Solomons explained, “the stream hurled itself with torrential force over a series of falls and cascades the most striking and magnificent I have yet encountered in the Sierra.” At the top of the thousand-foot climb along the waterfalls lay a several-mile-long stretch of pristine and forest-fringed meadow whose beauty rivaled that of Yosemite’s famous Tuolumne Valley. Solomons called it “one of the fairest paradises of the nowhere unlovely western slope of the Sierra.” He marveled at the fact that its “difficulty of approach” had kept it from being overrun by the hundreds of thousands of grazing sheep that John Muir, a decade earlier, had famously referred to as “hoofed locusts.”

At the southeastern edge of what we now know as Evolution Meadow, Solomons and Bonner encountered and ascended another gorge. As he first described it in his 1896 report, Solomons referred to it generically as the Middle Fork of the San Joaquin; later, he named it Evolution Creek. As the two men continued to climb the gorge in a southeasterly direction, they saw a “peaked and pinnacled wall” to their immediate south whose looming elevation above them (they were already well above 10,000 feet) ranged between 1,500 and 3,000 feet. Those imposing summits, he wrote, deserved to be thought of as “beautiful monuments rather than mountain peaks.” In the days following his and Bonner’s failed attempt to surmount the Goddard Divide, Solomons named each of them after his scientific and scholarly heroes: Charles Darwin, Thomas Huxley, Herbert Spencer, Alfred Wallace, Ernst Haeckel, and the philosopher John Fiske. These men, as Solomons wrote in his 1940 retrospective, had been so “at-one in their devotion to the sublime in Nature” that only these massive rock towers could suffice to monumentalize their legacy.

I sat on my unsaddled bronco facing east and gazing in utter fascination at the most beautiful and the most mysterious sight I had ever seen.

At the base of these heights lay an additional, albeit less intimidating wonder. Hikers all up and down the John Muir Trail still speak of this “fine sheet of water,” as Solomons described it, in reverential tones, whether or not they have heard of the Jewish explorer who named it Evolution Lake. I first encountered the lake’s glimmering 2-mile length (as a northbound hiker, I had approached it from its opposite end, having come over Muir Pass earlier that morning) on the 10th day of my end-to-end hike of the John Muir Trail. What I saw ahead and below me as I descended along its rim would have made an appropriate book jacket for Dante’s Paradiso. Admittedly, some of my excitement in that moment came about because I knew I’d be able to take my 40-pound backpack off as soon as I could claim a campsite on the lake’s shore. In an inadvertent accordance with its name, its appearance, at least in summer, has undoubtedly changed since Solomons and Bonner first saw and photographed it in 1895. Every evening from late June to early September its northern end is dotted with multicolored tents. As many as two dozen backpackers bask on its rocky shore, hydrating their meals with water that they’ve fetched out of its frigid depth.

Solomons knew that Evolution Lake was a place of signal importance and also of contradictory implications. “Nowhere more generous is the recompense that awaits the wearied traveler” to its shores, he wrote, highlighting its refugelike qualities. At the same time, he also intuited a profound connection between its apparent isolation and the extreme density that characterized the population centers of his home state of California. “Such is the birthplace of the San Joaquin,” he wrote, “the origin of that river which turns a hundred mills, irrigates a million acres of grain, fruit, and vine, and which imparts fertility and beauty to the largest and richest of California’s valleys.”

Evolution Lake is still nearly as “difficult of access” as any place in the nation’s most populous state can be. When Solomons wrote about it in 1896, he and Ernest Bonner may well have been the only people who had ever seen its shore. For a person of Solomons’ simultaneously scientific and reverent sensibility, the convergent facts of the lake’s spectacular beauty, geological uniqueness, and status as the source of the San Joaquin were points of inspiration and attraction.

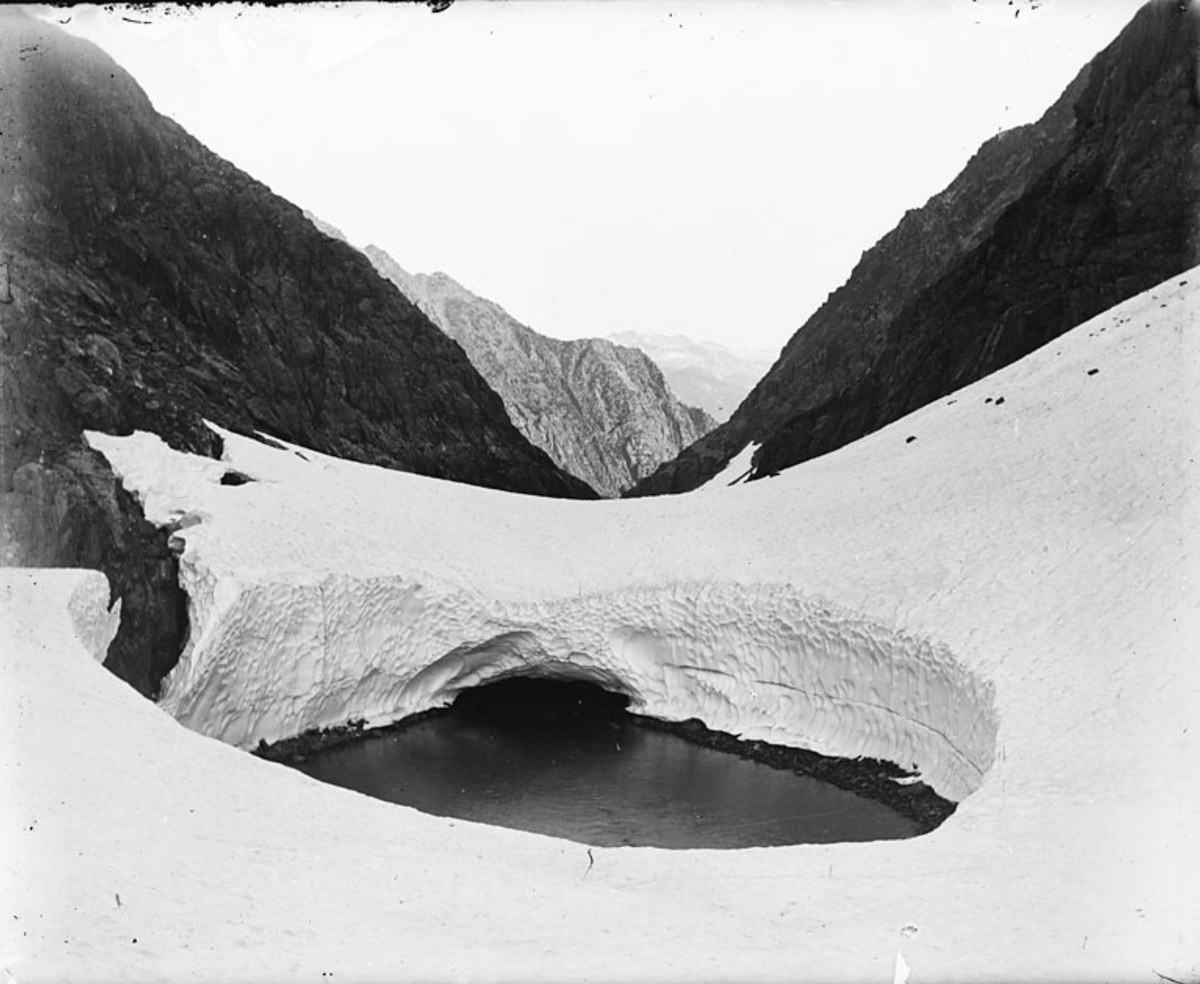

Snow Tunnel, Enchanted Gorge, Sierra Nevada photographs / Taken by Theodore Seixas SolomonsBANC PIC 1971.061: 50, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

At the end of the day on which they’d visited Evolution Lake, Solomons and Bonner camped at the foot of the peak that he’d just named Mount Huxley. They didn’t realize it at the time, but this particular campsite lay within 2 miles of the pass they were seeking. Indeed, as Solomons slept, he dreamed that his “task was fully done.”

Was he also imagining the backpackers who would eventually converge there? In his dream, “A well-marked trail led from the distant Yosemite past the long lake, up the snow-basin, and over the divide to the King’s River.” It was one thing to have been a teenager fantasizing from the lowland safety of his uncle’s pasture about an imaginary trail passing along the crest of the Sierras’ “flashing teeth.” It was another to picture the future trail at a moment when he was several days into a journey along the mountains’ spine, at such an enormous remove from the slightest reminder of civilization. Solomons “hope[d] that his dream was prophetic.” He knew that “the way was clear” and that “only the trail wait[ed] to be built.”

The snowstorm came the following day, as Solomons and Bonner climbed and then descended Mount Goddard in their attempt to locate the pass he’d just dreamed about. The gorge in which they sought and found shelter and warmth over the course of the next several days would prove to be a dead end of sorts, but few dead ends in the world can possibly have been so densely packed with scenic features. Traveling headlong down the south side of the mountain, they entered an area that remains trailless to this day. Solomons called it the Enchanted Gorge. In the words of a hiker who visited it in 1996, it still qualifies as “one of the most remote canyons in the Sierra Nevada.”

The Enchanted Gorge, as Solomons first described it, “was guarded by a nearly frozen lake, whose sheer ice-smoothed walls arose on either side, up and up, seemingly into the very sky, their crowns two sharp black peaks of most majestic form.” He called the peaks Scylla and Charybdis. After gingerly making their way around the edge of the lake, the travelers followed a snow-choked “road” through the gorge, descending “as though into the bowels of the earth,” all the while glancing upward at “black, glinting, [and] weird” walls whose 2,000-foot summits they could barely see. Solomons captured the otherworldliness of the gorge in the photographs he took while there. Two of his most striking images, “Rotunda in the Enchanted Gorge” and “Snow Tunnel in the Enchanted Gorge,” relay the beauty and desolation of the place in stark detail—the thick cover of snow, the jagged rocks, the indifferent sky, and nary a sign of vegetation even in the far distance, let alone of animal or human presence of any kind.

For all of its wonders, the journey into the Enchanted Gorge was not bringing them any closer to a crossing of the Goddard Divide, but they weren’t aware of that fact yet. On their southwestern trajectory out of the wilderness, Solomons and Bonner entered another deep valley formed by the Middle Fork of the Kings River called the Tehipite (fittingly, today’s Theodore Solomons Trail passes through that area). They exited the wilderness at Simpson Meadow on July 28, having logged 200 miles of hiking through places that very few, if any, other human beings, had ever seen.

Solomons and Bonner had come achingly close to establishing the link across the Goddard Divide, but even though they didn’t succeed in reaching that objective, Solomons was comforted by the fact that they had been the first people to pass through and record their trek through Evolution Valley and its environs. He was grateful for having gained an approximate sense of where the pass lay. The simple fact that no one else would even come close to locating or crossing that forbidding and barely accessible barrier for another 12 years is a testament to the significance of his and Bonner’s adventure in the annals of Sierra exploration and mapping.

The Rotunda, Enchanted Gorge, Sierra Nevada photographs / Taken by Theodore Seixas SolomonsBANC PIC 1971.061: 49, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

In 1896 Solomons made two trips in the region north of the Goddard Divide. The second of the two, during which he successfully led an official Geological Survey party through the territory around mounts Lyell and Ritter and the Minarets that he had first visited and mapped in 1892, would prove to be his final outing in the Sierras for several decades to come, and also the last time he would be either making or following his own path through the mountains.

The events of 1897 led to a drastic change of venue for Solomons. In the flush of excitement surrounding the gold strikes in the Yukon, he traveled to Alaska and put family money to use in establishing himself there as a mine owner. He did return to California some years after the turn of the century, visited the Sierras on multiple occasions, and even ended up building and raising his children in a house that he called Flying Spur, on the fringes of Yosemite National Park. The most rugged phase of his mountaineering and exploration career lay behind him, however, and his active contributions to the development of the John Muir Trail had come to an end. In the deliberations that took place between its official commissioning in 1915 and the completion of its final portion in 1938, Solomons weighed in freely but commanded little authority.

The fact that Theodore Solomons was a Jew and a direct descendant of one of North America’s oldest Jewish families wasn’t the sole reason for his descent into obscurity. In the conclusion of her 1988 biography, Solomons of the Sierra, author Shirley Sargent suggests that underlying antisemitism might have been one of several factors, but her 1983 interview with Ansel Adams comes across as something of an afterthought. The famed landscape photographer’s actual words, at least as Sargent quotes them, were that “his Jewishness influenced his relationships and there was a silent racism in the Bay Area society.”

However, while Solomons never denied or obscured his Jewishness, he was not active in Jewish life, either in the Bay Area or in any of the other places he lived during any period of his life following his bar mitzvah. The Solomons clan were not assimilationists, but they had been mixing freely with non-Jews since the colonial era. As Mark Solomons, Theodore’s great-great-grand-nephew, pointed out to me when I interviewed him recently, “This was a lineage that was very American.”

Solomons’ love for the wilderness was a function of his imaginative proclivities, his geographic proximity to the Sierras, and his acquaintance with other young Californians who shared in his passion. If Solomons’ Jewish heritage is relevant within the context of his explorations in the Sierra it is because it is a reminder that we don’t spend enough time thinking about how Jews in general have contributed to and shaped the cultural history of the North American landscape. Indeed, if there is one disconcerting element of his story it is the fact that, like any number of other stories in which Jews figure as active participants in quintessentially “American” endeavors, it sounds surprising to us in the first place. If Jews feel pride and gentiles are shocked upon hearing that Solomons’ great-great-grandfather was a proponent of the American Revolution who was an honored guest at George Washington’s 1789 inauguration, it is only because the dominant historical narratives frame early American history as a purely Protestant affair.

Solomons ended up building and raising his children in a house that he called Flying Spur, on the fringes of Yosemite National Park.

As the trail that he had first imagined in 1884 began to take shape after Muir’s death, Solomons referred to it as the “High Sierra Trail.” In 1915 the Sierra Club decided to name it for their illustrious founder—the man whose writing and activism had first introduced the Sierras to public consciousness in America. Solomons readily acknowledged the wisdom of doing so. He did not hesitate, however, to contextualize his approval of that act and to remind his fellow club members of the facts behind the trail’s history. “Muir is a better name to conjure with,” he said in a letter to one Sierra Club member who had just published an article on the trail’s origins, “but mine the idea, mine the pioneering.”

John Muir’s reputation has come under renewed scrutiny owing to his alleged ties to a prominent eugenicist and his numerous disparaging comments regarding Chinese immigrants and American Indians. It is an appropriate time to revisit the mountains’ cultural significance and the trail’s namesake’s history. If Theodore Solomons’ involvement in that story has anything to teach us, it is that ideas about the wilderness, as contrasted with the wilderness itself, are entirely human constructs. Commemorating Muir, or deciding to tone down our commemorations of him, is a choice that we make within the narrow framework of human history. The natural world will always remain indifferent to our discursive dilemmas. In 2018 a movement to rename the John Muir Trail the Nüümü Poyo, or “People’s Road,” arose among certain advocates for tribal rights who wished to draw attention to the Sierras’ Native American heritage. The Kern Kaweah chapter of the Sierra Club drafted a refutation of this proposal, albeit in as culturally sensitive a manner as they could muster. The report gave perfunctory attention to Solomons’ and other Sierra explorers’ roles in helping to create the trail in order to make its wider case in favor of honoring precedent. Why rename the trail, the authors of the report asked, when it was already, by definition, a memorial—“a human-constructed asset”—and not a natural feature like a mountain or a lake? That the trail’s name had long since memorialized the Sierra Club’s reluctance to honor an American Jew’s contribution to one of its best-known legacies apparently went without saying.