Kabbalah Trees

The story of a former converso’s invention of the Lurianic ‘ilan’

At the time of R. Jacob Zemah’s (ca. 1578-1667) arrival, it was still easier to acquire Lurianic treatises in Safed than anywhere else. R. Hayyim Vital (1543-1620) had resettled in Damascus in 1594, Ez Hayyim (Tree of Life—his magnum opus and summa of Lurianic Kabbalah) in tow, but many of his other works had been leaked before his departure. As the story goes, while Vital was briefly incapacitated by illness, a number of his early writings—not including Ez Hayyim—were “borrowed” and copied over three days by 100 scribes. The resulting bootleg treatises were precious contraband; Zemah, a former converso who fled his native Portugal as an adult, spent the last of his savings acquiring these books in Safed. “I sold all the silver and gold that I had and bought books,” he recalled, “and [especially] books of the Rav [Isaac Luria (1534-1572)], may his memory be a blessing in the World to Come.” The investment helped him establish a modest business model that allowed him to continue his important work. Zemah received donations from those whom he permitted to copy his manuscripts. He would then proofread, correct, and annotate the copies. His master copies were standardized and indexed for page-specific cross-referencing. Such assiduous editorial practices were a hallmark of Zemah’s scholarly work throughout his life.

After roughly a dozen years in Safed, Zemah went to Damascus to study with R. Samuel Vital, a great kabbalist in his own right and keeper of his late father’s Ez Hayyim. Why Zemah waited so many years to pursue study with Samuel is unknown; perhaps he did not want to present himself to Vital’s heir before he felt worthy and ready. Although Samuel would eventually allow eminent visitors to inspect the manuscript, during Zemah’s years in Damascus (ca. 1632-1640) the only way to study Ez Hayyim was to listen to Samuel read it aloud. This he did every Friday night and again from midday to nightfall on Saturday. The listeners could not take notes on the Sabbath. The plan had a flaw, however; Zemah remembered what he had heard and reproduced it in writing after the Sabbath ended each week. His library of Lurianic works therefore expanded to include a series of books based on these Saturday night transcriptions, prefaced by apologies for possible errors resulting from lapses of memory.

Zemah resettled in Jerusalem around 1640, the change of place once again effecting a change in his Lurianic library. After nearly two decades of struggling to cobble together a collection of Vital’s writing by hook or by crook—from the contraband treatises in Safed to the books based on Samuel’s recitations in Damascus—Zemah finally hit the proverbial jackpot in Jerusalem. Soon after his arrival, he obtained a significant cache of Vital’s original autograph manuscripts. There was a catch, though: They had been underground for decades. In a fit of neurotic fury, Vital had decided to destroy them before leaving for Damascus, burying them in the genizah of Safed. The manuscripts reached Zemah in various states of decay. One treatise survived miraculously intact, still bound and missing only its title page and some of the letters bordering its damaged margins; Zemah gave it the name Ozrot Hayyim (Treasures of Life). It was an orderly extended exposition of the grand emanatory scheme that Vital distilled after completing his first phase of writing in the years after Luria’s death. The decomposing and disordered pages of Vital’s other books were painstakingly reconstructed and copied by Zemah, who endeavored to reassemble each one in its original form. Zemah ran his own bet midrash in Jerusalem as a restoration and reproduction lab, with as many as nine scribes working under his supervision. No fewer than five “new” Vital works resulted from their efforts.

Zemah’s dedication to restoring each of Vital’s texts—an expression of his antiquarian scholarly sensibilities—was unique. R. Samuel Vital, in his Shmonah shearim (Eight Gates), preferred thematic redaction, as did Zemah’s student R. Meir Poppers. To put this another way, in editing Vital’s texts Zemah strove to recover what had been written, Poppers to create what should have been written. Zemah’s Jerusalem series thus rendered his Safed and Damascus corpora effectively obsolete. But the Jerusalem restorations would soon fall victim to their own success. Not long after Vital’s treatises had been salvaged from oblivion by Zemah and meticulously recreated, they became obsolete thanks to their cannibalization in the eclectic Poppers edition of Ez Hayyim, which quickly became the canonical expression of Lurianic Kabbalah.

These redaction details are relevant to the history of ilanot—or kabbalistic trees, referring to the genre of diagrammatic/arboreal scrolls/rotuli—because Zemah made his pioneering ilan in Damascus. As he described it, the diagrammatic presentation of the ilan was fully annotated and framed by texts and commentaries that included the page numbers of their sources in the master copies of his Damascus library. With the eclipse of that library—first by the new Jerusalem editions and shortly thereafter by the new Poppers edition of Ez Hayyim—the value of Zemah’s fully annotated ilan plummeted rapidly.

Before turning to Zemah’s account of the ilan he made in Damascus, which has not reached us in its original form, it is worth asking what we can learn about Zemah and visual Kabbalah from his diagrams that have survived. He carefully copied the original diagrams in Vital’s autograph works when he restored them in Jerusalem in the 1640s, treating them as authentic expressions of Lurianic thought that deserved the same respect as the texts. The restored volumes painstakingly preserve and present them, and his annotations include diagrams of his own making. These original drawings show Zemah, the visual commentator, thinking with diagrams.

A modest marginal note in Zemah’s own hand provides a fascinating example. The note appears in the oldest known copy of Zemah’s restoration of a buried Vital treatise to which he gave the name Toldot Adam (Generations/History of Adam [Kadmon]); it had lost its title page in the moldy genizah. Vital’s original was composed in the early 1590s as a summary of the emanatory mechanics of Luria’s system, and it came to be known as Mevo she‘arim (Entrance to the Gates). The mid-1640s manuscript, produced in Zemah’s bet midrash atelier, features marginalia and an index in Zemah’s own hand. Near the beginning of the cosmogonic exposition, in which Vital explains the emanation of the Worlds one within another, Zemah poses a question in the margin: Might the Worlds have emanated one after another, each as its own circle? To make his meaning clear, he refers the reader to a diagram he has devised himself, “as in this drawing” (fig. 1). The drawing, a circle in which three smaller circles are aligned vertically, does more than illustrate his question, however: It provides him with the answer. Considering it, Zemah writes, one can immediately see the problems. If each of the internal circles—of which, he points out, he has only bothered to draw three—were independent, their connection to Ein Sof would be identical. There would thus be no difference among them. Furthermore, were they arrayed in such a manner, the vacated space (hallal) within Ein Sof would be in a state of disequilibrium: The top and bottom circle-worlds would be closer to the all-encompassing circle than the middle one. This diagram neither visualizes nor clarifies a text for the reader; it is, to borrow Nelson Goodman’s term, a “counterfactual conditional” diagram visualizing a false “if clause.” Zemah’s diagram presents a false visualization of Vital’s cosmogonic teaching, and by examining it—that is, thinking with it—one can understand why the interpretation it represents is incorrect. This modest figure shows us Zemah’s visual kabbalistic thinking in action and suggests just how deeply implicated diagrams might be in kabbalistic epistemology. Its reception history is also revealing. As a rule, Zemah’s autograph marginalia were integrated by the copyists working under his supervision into the more sophisticated mise-en-page of second-generation manuscripts. In this case, not only was the diagram preserved in such early copies but it was also enlarged, the clearest possible indication of its importance (fig. 2).

Although that earliest copy of Toldot Adam shows us Zemah’s original counterfactual-conditional diagram, it no longer includes large-format foldout diagram pages. We can be certain that these oversize pages were torn out and lost given their preservation in copies in which they have been downsized to fit on a standard page. A fine example can be found in a copy executed by R. Samuel Laniado of Aleppo (d. 1750). Laniado copied Toldot Adam roughly a century after its restoration by Zemah, rendering its large diagrams on octavo-size pages. These allow us to see other facets of Zemah’s relationship to images. As in the last example, they show Zemah reading Vital visually but also demonstrate his conviction that Vital’s images are no less “torah” than his texts. As such, they deserved meticulous preservation even when Zemah had his own, somewhat different visualization of the same material. Zemah took Vital’s diagrammatic expositions seriously, and this fundamental appreciation of the communicative, ideational power of images, coupled with Zemah’s principled antiquarianism, ensured their preservation.

Laniado’s copy, which we have every reason to believe was faithful to its source, presents the reader with two facing pages, each of which is dedicated in its entirety to an intricate diagram (fig. 3). They visualize the same ideational content, so their juxtaposition, rather than conflation, reflects their significance in Zemah’s eyes. Laniado’s marginal notes and his care in producing these finely executed copies show that he took them no less seriously. Zemah captions each with his typical transparency. The first (fol. 49b, reading from right to left) reads, “Zemah: This drawing [ziyyur] I have drawn on the basis of the Rav [Vital] of blessed memory’s words on the preceding page, as you will see.” The second reads, “Zemah: This drawing is as it was drawn and written by the hand of the Rav of blessed memory.” Vital’s diagram was a visualization of the ideas expressed in the text immediately preceding it. Zemah, reading the same text and having carefully scrutinized Vital’s diagram, thought it would be useful for his readers to study his own visualizations as well.

The two diagrams, not surprisingly, have much in common. Zemah offered a more thorough graphic elucidation than did Vital by adding details and leaving a bit less to the imagination. Comparing the two, the following differences stand out:

1. Zemah replaced Vital’s semicircles with full circles.

2. Where Vital wrote “the 10 circles of,” Zemah replaced the inscription with 10 circles.

3. Zemah’s reorientation of the diagram enabled him to distinguish between the right and left of the major parzufim. To the central shaft he also added various “windows” (halonot), cosmic “Chutes and Ladders” connecting higher (outer) and lower (inner) elements.

4. Concentric-circle diagrams need to be labeled only on one side—or, as Vital had opted, show a semicircle—because the referent of each band remains constant. The full circles of Zemah’s version nevertheless permitted him to show something that could not be pictured in Vital’s diagram: the linear channel traversing the circles from the top almost to the bottom. The cosmogonic text had explained that the channel had to stop before piercing the bottom. Were it to extend through that bottom, the light of Ein Sof within the channel would reconnect to Ein Sof surrounding the circles, short-circuiting creation and restoring the pre-zimzum (divine auto-evacuation) primordial simplicity. Zemah’s image brings home this point tangibly.

Zemah did not deem it necessary to replicate every last detail of Vital’s diagram in his own, including the inscription of Ein Sof in the outermost ring, the recurring inscriptions of “light surrounding circle/light within circle,” and the innermost circle bearing the label “Beriah klippot” ([World of] Creation—[evil] shells).” After all, his own diagram was not meant to replace Vital’s.

It should hardly come as a surprise to find Zemah reminiscing in the 1640s about the visually oriented projects that he had undertaken while still in Damascus. Marrying his organizational and pedagogical orientation to his profound appreciation for the power of images, he had created a series of charts. The large format enabled him to present structured presentations of material not easily accommodated on the pages of a book. One, he tells us, was devoted to the grades of prophecy according to Vital’s Sha‘ar ruah ha-kodesh (Gate of the Holy Spirit); we can only presume that it integrated considerable textual material in the framework of a boldly lettered outline. Two others provided kavanot (the intentions that are to accompany the performance of the commandments) for short but significant liturgical performances: the Shema (“Hear, O Israel,” Deut. 6:4) and the Kaddish (sanctification). These kavanot attended to the secrets encoded in every word and the vocalized divine names associated with them; gazing upon these names was essential to the performance of the technique. By transferring them from the crowded pages of handwritten codices to large sheets of paper, Zemah must have hoped to facilitate the successful implementation of these demanding practices. He was ahead of his time and perhaps ours as well; a look at any Lurianic siddur (prayer book) shows just how many pages must be turned to get through these prayers. If he were alive today, Zemah might have suggested praying with a teleprompter app or even designed one himself.

The large-format project to which he devoted his richest account, however, was “an ilan of the parzufim [divine personae of the Lurianic system].” The passage in Zemah’s introduction to his commentary on the Idra rabba, titled Kol be-Ramah (A Voice Is Heard in Ramah, from Jer. 31:15), in which he describes his ilan project, could hardly be more consequential to the history of the genre. The two earliest manuscripts that include the introduction, one in the British Library and the other in the Jewish Theological Seminary, date to the 17th century. They present us with slightly different versions, perhaps reflecting updates made by Zemah over the years to different master copies. Given its significance, I translate the passage as it appears in both versions:

London, BL Add. MS 26997, 1b–2a (Avivi §836)

Afterward, on one large sheet of paper, I wrote an ilan of the parzufim ordered in drawings (mesudarim be-ziyyurim) as mentioned in the books. The parzufim and their subsections are sectioned as they enrobe (mitlabshim) one another. A full explication surrounds, with a reference to the page of the work from which I have copied [each element].

New York, JTS MS 1996, 1b (Avivi §834)

Afterward, on one large sheet of paper, I wrote an ilan of the parzufim, according to the order written in the books. I clarified each and every element (davar). The five parzufim I drew in sectioned units (be-frakim ha-nehelakim) [connected] from one to another and from parzuf to parzuf and from sefirah to sefirah. The explication of every element is written surrounding it, each with a reference to the place from which I took it.

The two versions have much in common. On the basis of content I would be hard-pressed to decide which might have been the first draft and which the second, if indeed the differences reflect Zemah’s own revision. The ostensibly later copy does not necessarily reflect a later version of the text. They are, in any case, in complete agreement on the fundamentals. Zemah drew an ilan of the parzufim on a large sheet of paper; he ordered them in accordance with the teachings in the works of Vital at his disposal; and he framed the diagrams with elucidating texts. Zemah’s use of the term ilan must have been a conscious invocation of the long-established genre. He describes his biur (explication) surrounding the diagrams as anthological and based on primary sources. Zemah provided each with a full reference—using a frequently recurring term in his vocabulary, moreh makom (lit., showing the place)—noting the name of the book from which he had adduced it as well as the precise page number. The assembled sources would have provided basic characterizations of each of the parzufim and detailed the interfaces between them. In fashioning his innovatory ilan in this manner, Zemah was effectively updating the established convention of ilanot. The embedding of texts that taught the fundamentals of kabbalistic cosmogony in and around a large diagrammatic representation of the divine structure was, after all, the essence of the classical ilan. The earliest ilanot arrayed a single introduction to (or “commentary on”) the sefirot on the parchment but, as we have seen, 16th-century ilanot could also be ambitiously anthological. Zemah’s juxtaposition of elucidating primary sources and their diagrammatic representations was therefore traditional.

Teasing out the significance of the differences between the versions, we note that the British Library witness is more concise, thanks to its reliance on kabbalistic shorthand. In it, Zemah describes having divided up the parzufim to show their sections “enrobing one another” (ha-mitlabshim mi-zeh la-zeh). Using the technical language of hitlabshut (enrobing or “engarmentation”) permitted greater brevity of exposition. The longer version, in the New York JTS witness, does not use that term but opts instead for a richer description of the diagrammatic visualization. In it Zemah has “clarified every single thing” (birarti kol davar ve-davar); drawn precisely five parzufim; and pictured them in a manner that reveals their relative positions and precise sefirotic interfaces. He seems pleased by the granularity of his visual exposé, having found a way to show the process of hitlabshut down to “sefirah-to-sefirah” resolution.

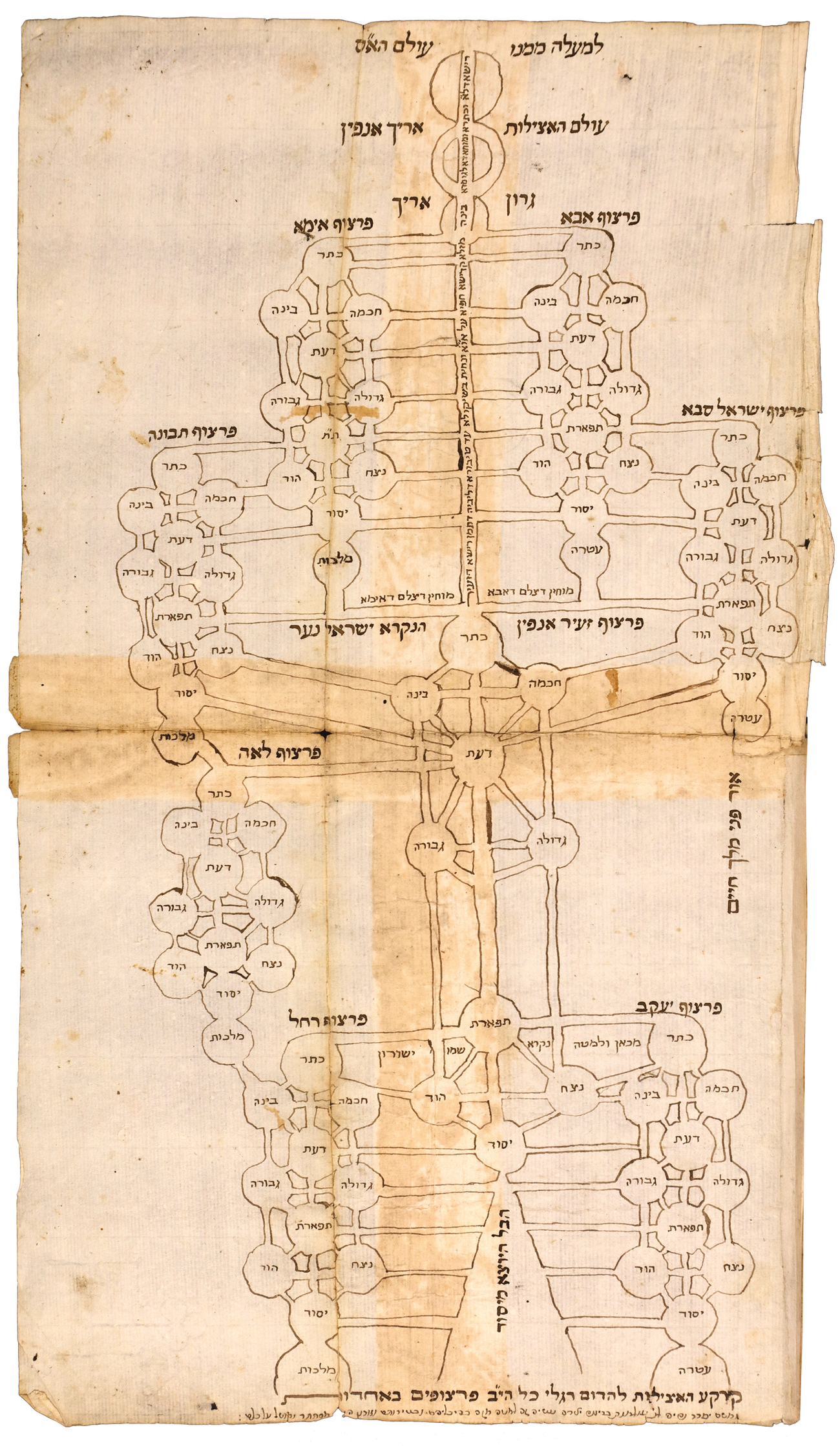

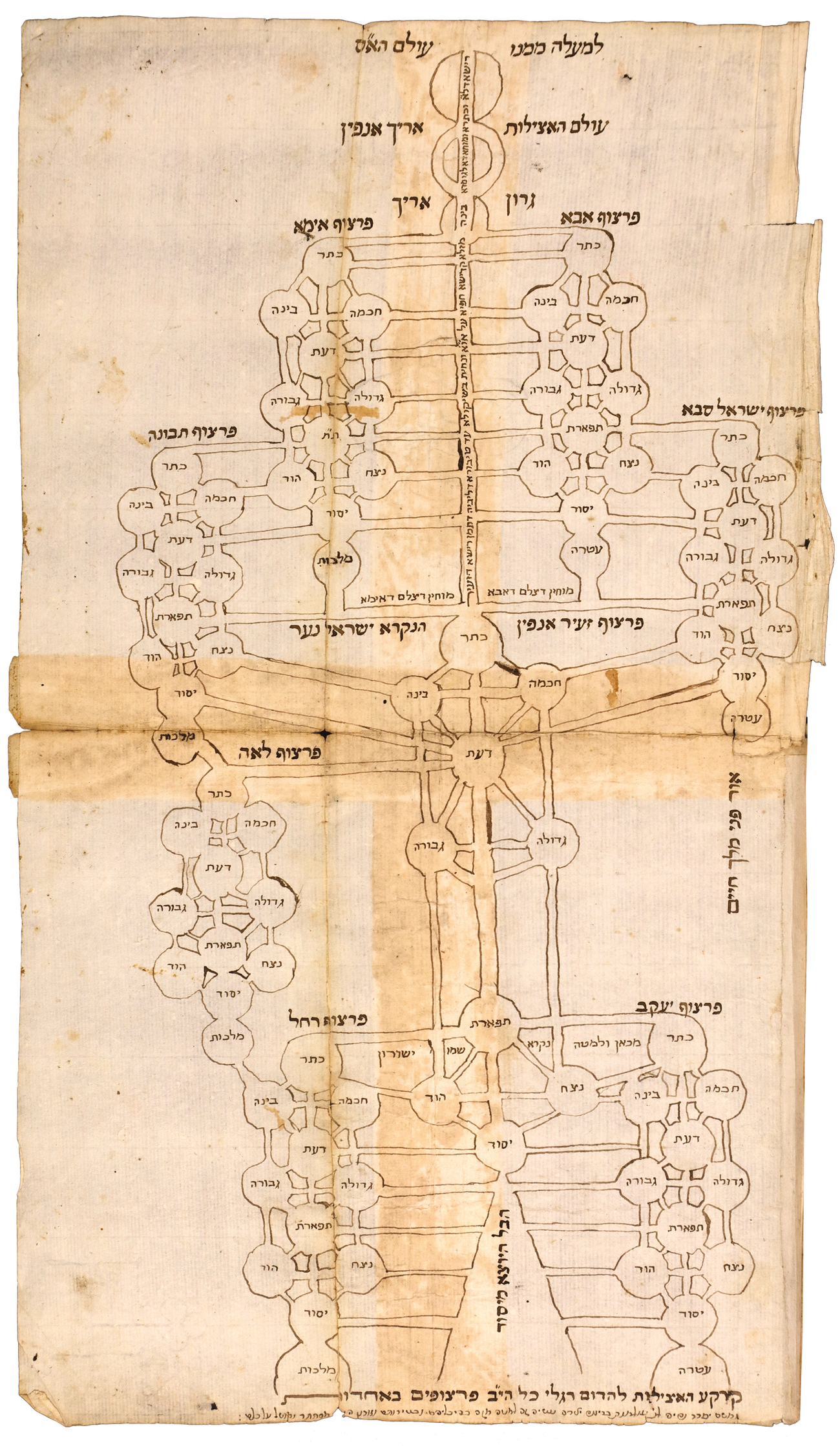

This, then, is the verbal description of the first Lurianic ilan. Does it correspond to anything we see among the earliest Lurianic ilanot? I answer with an image (fig. 4). For now, it is sufficient to observe the manner in which the arboreal figures of its bottom half—each representing a parzuf—are interlinked. This array of small trees exposes the minutiae of these enrobings, “sefirah to sefirah.” There is nothing quite like it in the diagrammatic repertoire of the Lurianic kabbalists. Its early incorporation and endurance as a constitutive element of early Lurianic ilanot strengthens the case for attribution to an authoritative creator. In light of its congruence with Zemah’s description of the diagrammatic heart of his ilan, we can presume that this version preserves his innovative visualization, albeit shorn of the original framing commentary.

Zemah’s ilan made its European debut in the diagrammatic appendices to early copies of Vital’s Ozrot Hayyim. Vital’s lucid, concise, and mechanistic presentation of Lurianic cosmology was particularly well-suited to graphical visualization. Even after it was “swallowed up” in Poppers’s Ez Hayyim, it remained a favorite of some kabbalists, first and foremost R. Moses Zacuto (1625-1697). Zemah recovered and restored Ozrot Hayyim in 1643; by 1649, Zacuto had obtained and annotated a copy. The 1649 witness includes a fascinating note by Zacuto in which he asserts that among the schemata rejected by Cordovero were, unbeknown to him, representations of particular parzufim. Thus, Zacuto claimed, a particular array of the sefirot, rejected by Cordovero in Pardes rimonim (Pomegranate Orchard) (6:2:2), in fact represents Arikh Anpin (Long-faced or Patient Divine Persona/parzuf). Zacuto then refers his readers to a diagram of Arikh Anpin based on that configuration, which he himself has drawn and inscribed on the following page (fig. 5). Although it is not found in the 1649 manuscript, subsequent copies of Ozrot Hayyim made under Zacuto’s direction and based on the 1649 master copy often present the “Zemah ilan,” showing the sefirah-to-sefirah networked array of arboreal parzufim, adjacent to the Arikh diagram (fig. 6). Their juxtaposition in these codices undoubtedly inspired their coupling soon thereafter on dedicated parchment rotuli.

The heuristic value of the sefirah-to-sefirah parzufic ilan, which probably reached Zacuto in the late 1640s along with other Zemah materials, would have encouraged him to preserve it. Zacuto saw to its inclusion in the copies of Ozrot Hayyim that he worked diligently to distribute far and wide. Zacuto’s transvalued classical ilan had an important contribution to make, but its raison d’être was certainly not to reveal the manner in which the lower elements of higher parzufim were “enrobed” by the higher elements of lower parzufim, something that Zemah’s ilan accomplished with unrivaled clarity. As these hitlabshuyot (enrobings, plural) were at the core of Lurianic theory and practice, the question of how best to visualize them graphically was of no small importance. Vital’s synoptic circles showed the entire structure at a glance without, however, exposing intra-parzufic interfaces. Zemah seems to have been the first to come up with a workable approach to doing so. Just as Zacuto restored a “rejected” classical arboreal diagram of the sefirot to become the image of Arikh, Zemah, in his own kabbalistic return of the repressed, revived both the iconic classical schema and the ilanot genre to accomplish his goal.

As Vital saw them in a dream, the parzufim were “the picture of the 10 sefirot, three-three-three, one above the other.” Although Zemah’s description of his ilan does not state explicitly that he represented each parzuf as a sefirotic tree, the parzufim are routinely described as configurations of the 10 sefirot; the arboreal schema would be presumed. The tree could also represent the specific “docking” of a higher into a lower parzuf, its hitlabshut, such as the Nezah-Hod-Yesod of one enrobing in the Hesed-Gevurah-Tiferet of another. Even without the inspiration of Vital’s dream, Zemah would have asked himself how best to visualize this process and, more likely than not, arrived at this solution.

Zemah’s work—as a redactor of Hayyim Vital’s texts and as a designer of ilanot—was soon eclipsed by that of his student Meir Poppers. Poppers was not merely another redactor in the chain reaching back to Vital; he was also the kabbalist responsible for editing Vital’s materials into their canonical expression, the work known ever since as Ez Hayyim. By 1651 Poppers had completed his reediting of the entire corpus of Vital’s writings—into which all the Zemah editions were subsumed—under the topical rubrics Derekh (The Path of), P’ri (The Fruit of), and Nof (The Bough/ Crown of) Ez Hayyim (Tree of Life/Hayyim). The second and third sections collected the teachings pertaining to the intentional performance of the commandments, various commentaries of canonical literature, and teachings on reincarnation. The first, dedicated to the orderly presentation of the grand Lurianic emanation narrative, quickly became the standard work known simply as Ez Hayyim.

Poppers, like Zemah, took images seriously. He was well aware of Vital’s graphical visualizations and considered them to be of the highest epistemic and hermeneutic value. In one of Vital’s more ambitious efforts, called by Poppers “the drawn page” (daf ha-ziyyur), Poppers believed he had found the key to settling a fraught question of Lurianic exegesis. It was a question that texts alone could not resolve: Where was the precise location on Adam Kadmon from which the nekudim (speckled) lights emerged? The text was clear; they emerged from the tabur.

The problem was whether that term referred to the solar plexus or to the navel. Poppers argued that Vital’s “drawn page” diagram left no room for doubt; it meant the former. The marshaling of a diagram to settle a contested hermeneutical question attests to the authority of Vital’s image in Poppers’ estimation and, more broadly, to the fact that some teachings were more amenable to pictorial than to textual presentation.

Inspired by the precedent set by his illustrious teacher, Poppers also invested his energies in fashioning an ilan. Like Zemah, who thought it appropriate to offer his own more intricate version of a diagram by Vital, Poppers charged himself with pushing the ilanot genre to its very limits.

The excerpt is reprinted with minor modifications from J.H. Chajes, “The Kabbalistic Tree” (2022), with permission of Penn State University Press.

J.H. Chajes is Sir Isaac Wolfson Professor of Jewish Thought at the University of Haifa. He is the author of The Kabbalistic Tree and Between Worlds: Dybbuks, Exorcists, and Early Modern Judaism, co-editor of The Visualization of Knowledge in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, and the director of the Ilanot Project.