The Man Who Saved My Grandfather

A war reporter visits Slovakia to meet the peasant-turned-doctor who risked his life to hide Jews

Milan Hucko understood why his aunt begged his father to stop hiding the Jews. The anti-Nazi uprising in Slovakia was failing, and the occupying German army was a constant presence in his village. Everyone knew the penalty for hiding Jews: The invaders or their collaborators would kill you and your entire family. “I can understand, not everyone was willing to die,” Milan says.

Milan was 14 in the summer of 1944, when his family hid my grandfather from the Nazis. He was 89 years old when I went to Slovakia to interview him in November of 2018 and ask him why they decided to help save his life. I wanted to ask Milan what my grandfather had been through during a war that’s now almost beyond living memory.

But my curiosity went beyond my family’s history. Milan, I thought, could also explain what compels a person to risk everything to save a stranger in a time and place where neighbors kill one another and behaving with basic humanity can be deadly.

I have spent much of my career in conflict zones. For over a decade, I have covered war and violent social collapse, often reporting on conflicts inflamed by ethnic and sectarian divisons, usually in the company of other journalists, aid workers, academics and analysts. We grasped for whatever thin logic or meaning appeared in the spasms of violence we witnessed. We were like the journalists in Sarajevo described by Peter Maass in Love Thy Neighbor, his seminal work on the Bosnian civil war: “They were possessed by war, by the madness of war and by the presumption that they were acquiring the ability to see into people’s souls. It was true. They were getting closer to the truths of human nature, dark and horrible.”

I sought these dark and horrible truths in places like Iraq, Syria, Ukraine, the Central African Republic and Gaza. I tried to find something that could explain how people can embrace death and destruction on such an unfathomable scale. But in the course of my reporting, I would sometimes meet those on the opposite side of the moral spectrum: the minority willing to risk everything to rescue total strangers

Wars are propelled by an internal logic that becomes nearly impossible, and often actively dangerous, for the people caught up in them to reject. Ancient hatreds bubble to the surface. Lost territory must be reclaimed, old insults avenged. Crippling poverty, a changing world, dwindling resources, a rising demagogue—all can push entire populations to a violent breaking point. Not everyone, though, is willing to go along. Who has not asked themselves what they would do in such a situation? Who has not told themselves, or hoped, that they would be one of the few to resist the madness?

Milan held a very personal answer to these questions. The heroism of him and his family is literally the reason I exist. And, in a way, it was the reason I had been drawn into life in conflict zones.

When I was 22, I visited Auschwitz with my grandmother. It can be hard to grasp the significance of a place like that, decades removed from the horrors that occurred there, especially on a beautiful summer day. What I remember is watching my grandmother, then 80, walking the dirt paths and searching her memories. She muttered to herself, struggling to remember which housing barrack was which. But she wasn’t overcome with emotion.

She had spent years in the camps, primarily Auschwitz, after being sent from Slovakia as one of the earliest Jewish deportees in 1942. The number tattooed on her forearm was only four digits. She was imprisoned at Auschwitz, Mauthausen, Grossrosen, Bergen-Belsen, Breslau and the death camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau. She survived a death march and an examination from Dr. Mengele. Unlike her eventual husband, no one had been there to shelter her from the Nazis.

More than a decade later, I was in northern Slovakia in the small town of Vadovce, searching for the house where a 14-year-old Milan helped ensure that my grandfather did not also end up in Auschwitz. Vadovce is a picturesque Eastern European hamlet, nestled among hills and valleys. Crops grow in small tidy fields; there’s a church and a town square, a babbling stream and apple trees.

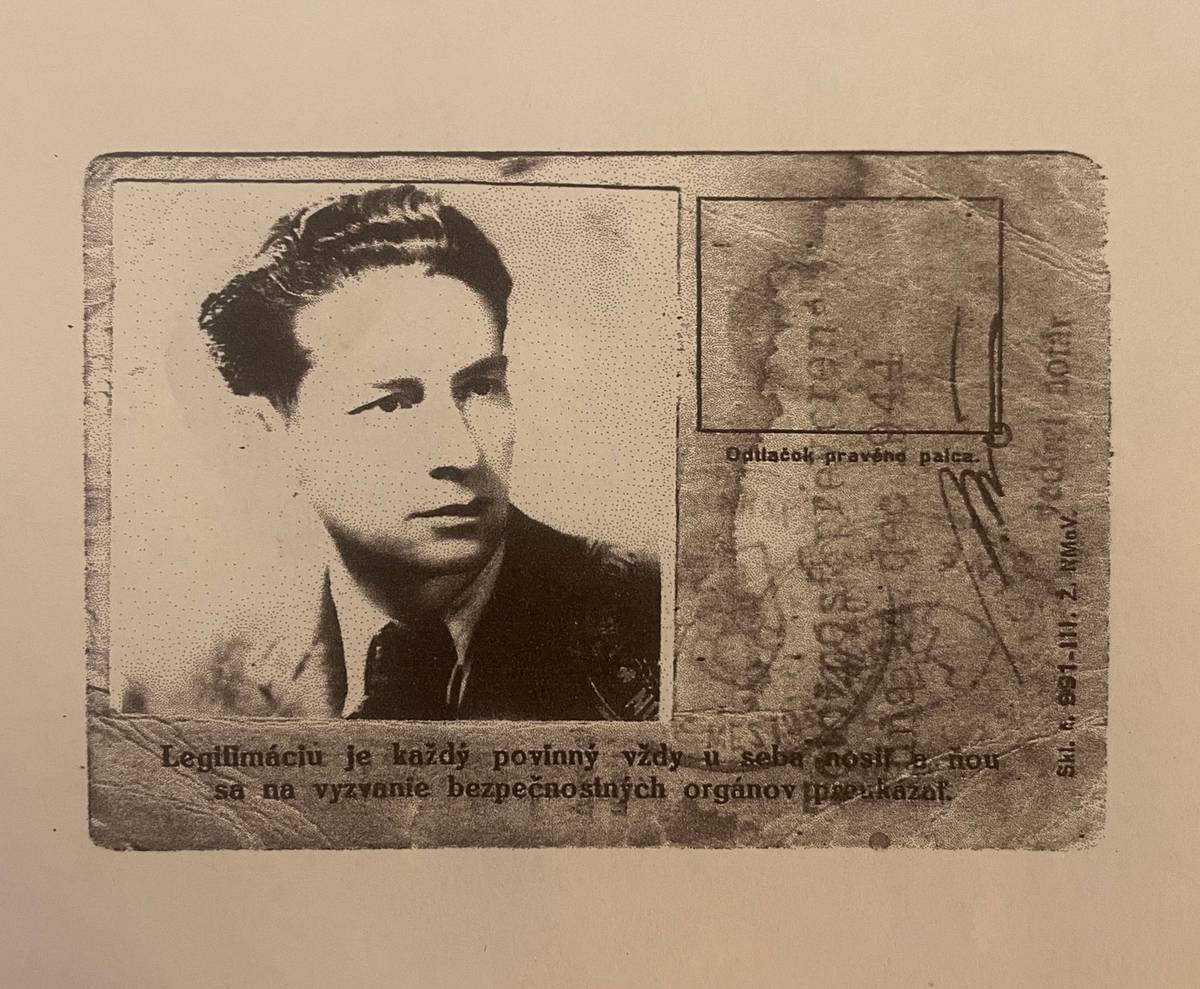

My father had given me a photo of the house from an old manila folder, which also contained a copy of my grandmother’s Auschwitz file and the fake identification papers my grandfather used during the war. The picture shows a simple structure, not more than a few rooms. The house isn’t there anymore, and neither is the barn where my grandfather first hid out. In its place is a small chemical factory and a parking lot. The economy is booming in Slovakia, and the flush times have even reached the periphery. The country manufactures more cars per capita than anywhere in the world.

By the time I went to Slovakia, all four of my grandparents, all Holocaust survivors, had passed. My last surviving grandparent died in 2016 when I was on a flight to Iraq to cover the operation to take Mosul back from the Islamic State. Previously I had missed my maternal grandmother’s funeral while covering the burgeoning civil war in the Central African Republic. There, some told me they had always lived peacefully next to people from other religions; others spoke of the rising hatred, the changing attitudes, their fear of what was to come and how it would shape their lives.

The Nazis exterminated nearly an entire generation of my family, including all of my great-grandparents who were alive at the time. Two of my grandparents were the sole surviving members of their immediate families. My paternal grandmother had survived Auschwitz, but her parents and six siblings did not. Milan and his family made sure her future husband, Abraham, survived, but Abraham lost his mother and four siblings; one older brother who fought in the forests with the partisans survived. My mother’s parents, both young and unattached, fled western Poland just after the Nazis divided up the country with the Soviets; both ended up as refugees in Siberian work camps before meeting at a displaced persons camp in Kazakhstan. Neither saw their parents again. Five of my grandmother’s siblings survived, along with four who were killed. My mom’s father, like my father’s mother, lost everyone in his immediate family.

The Holocaust was a specter of my youth, shaping how I came to view the world. It was a reminder of what people were capable of and the importance of keeping the human propensity for evil in the back of one’s mind. As a child, I would think about how much bigger my family would have been, how many more cousins I would have had, if the Nazi genocide had never happened. My grandmother would recall with a strange fondness how I was the first grandchild to ask about the tattooed numbers on her forearm. A blond child, I remembered being told that I was light-haired like my grandfather, and that this had enabled him to conceal his Jewish identity during the Holocaust. Perhaps I looked enough like him that I could also hide my Jewishness in a similar situation.

Back in Vadovce, I wanted to be sure I was looking at the exact place where the house stood. A man tending a garden across the street said he didn’t remember any house. But soon, a curious elderly woman approached and led me right back to the factory. “Here it was where the Huckos lived,” she told me.

I walked across the road and stood under an apple tree to snap a picture of the factory. There was no grand foundation left to help me imagine what had been there, no plaque marking where something extraordinary had happened. It was just a factory.

That morning I had set out at dawn from the town of Martin, where Milan Hucko lived. It is a popular ski resort area, carved out of heavy forests at the base of the Mala Fatra mountain range. An early morning mist hung at the edge of town. The dew on the grass was thick enough to drench my shoes. It was autumn, roughly the same time of year in 1944 that my grandfather had fled from the northeast of the country, in the same direction I had just traveled.

Milan was a spry 89-year-old. He had a lightness of spirit and was all smiles and hugs. His eyes gleamed, as if he was constantly about to tell a risqué joke, which he sometimes did, whispering with a nudge and a wink. He was dressed in a beige corduroy blazer and black slacks, as dapper as a man in his late 80s living in a small Slovakian town could hope to be.

We met him in a parking lot near his daughter’s house. She was worried about Milan doing the interview alone and was unsure of how he would fare emotionally. Discussing the war had a tendency to depress him, she said. She felt protective—some negotiation was required before she agreed to let me meet him. Despite, or perhaps because of, his heroism, Milan wasn’t fond of reminiscing about those times.

I hugged him tightly as tears flowed down both our cheeks. We had met when I was much younger, but I barely had any recollection of it. He would go on to tell me later that day, in an unusually reflective moment, that sometimes he stopped to think about how if his family hadn’t hidden my grandfather, my siblings and cousins and I wouldn’t be here. I told him I sometimes thought about that too.

Jews who survived the Holocaust emerged from the horror with radically different views of reality. There were those like my grandmother who greeted the world with the joy that only someone who is not supposed to be alive can feel. And there were those who viewed the world as if it had tried to destroy them and and never forgave it for doing so.

I was barely a teenager when my grandfather died. His mind had died years earlier, ravaged by Alzheimer’s and dementia. I never had the conversation with him about what it felt like to be hunted in a genocide. My memories of him are of a hard man, quick to raise his voice, gritting his teeth. Did the sharp edges develop after the war, when he had to rebuild his life with nearly everyone around him murdered?

It was only through trying to report this article that I learned a theory from my father. In Slovakia, the shipping of Jews off to the camps had taken a brief pause in 1943 before picking back up again in 1944. In that period, the Jews there were not safe, but they were not being hunted with the same intensity. In the summer of 1944, as the Nazis continued to collapse on the Eastern Front, it was clearly becoming dangerous again. Perhaps my grandfather tried and failed to convince his mother they needed to head into hiding or try to escape. He left to seek safety, and she was soon caught and shipped to the camps, never to be heard from again. Maybe he blamed himself for her death and could not forgive himself for surviving.

We left the parking lot and headed to Milan’s daughter’s house, a nice modern home just down the block. Milan had become a doctor after the war. He got married and had a daughter who became a judge and gave him three grandchildren. He was proud of his daughter’s success, and spared no effort in the guided tour he took me on, naming all the flowers and plants in her well-manicured backyard. Milan was prouder still of his grandchildren, as he showed off the various medals and award certificates they had received for arts and sports.

Every Friday, he and his 8-year-old grandson had “man’s night,” where they gathered at Milan’s apartment to watch Star Wars and eat pizza. The 8-year-old and his 11-year-old brother don’t know the war stories just yet. Milan’s 16-year-old granddaughter, a champion dancer, was old enough to learn what had happened during the war. She told me her grandfather was her hero.

On a sunny afternoon in September 1944, 14-year-old Milan arrived home from school and found a strange man in his backyard, working the sawmill with his father. He noticed that the man, who looked to be in his mid 30s, was dressed quite well, maybe a little too well, and was physically fit. Though clearly strong, he was unskilled at operating the small sawmill. Milan thought it odd that his dad would hire a man who didn’t seem to know what he was doing, but he was awed by the stanger’s physical strength. “If that guy hit me, I’d spend the rest of my life in the air,” he thought to himself.

His father introduced the man as Ondrej, a distant member of the family from near Bratislava, the Slovak capital. Ondrej’s actual name was Abraham Gold. He was a Jew from the east of the country. A horse trader, Abraham had so far been one of the luckier Jews in Slovakia, holding an exemption that a powerful former business associate had secured for him to prevent his deportation to the camps.

Slovakia was in chaos as summer turned to fall. The Nazis were panicking about the approaching Soviet army and sprinting toward their Final Solution to the “Jewish question.” All exemptions like Abraham’s were canceled, and after a brief respite, Jews in the country were once again under threat.

Slovakia belonged to a unique category in wartime Europe. In 1938, the Third Reich made a deal with the Slovakian government by which the country would split from Czech territory under German protection and form an “independent” rump state. This happened in 1939. While Slovakia was technically not occupied, it was not independent. It was a fascist-ruled vassal state fully aligned with Germany.

By 1941, the Nazi-allied government struck a deal with the Slovaks regarding the lingering issue of the country’s Jewish population: The Slovaks would pay the Nazis the equivalent of $200 per person to dispose of this despised minority community. The deportations started in 1942, and by the end of the first wave 58,000 out of the country’s approximately 100,000 Jews had been shipped to the concentration camps. Fewer than 30,000 of Slovakia’s Jews would survive the war.

In 1943, the deportations halted and restrictions lessened. It was clear to many in the Slovakian government that the Nazis were losing the war in the east. The Germans wanted the deportations to start up again, but the Slovakians were reluctant. But in 1944, the Nazis invaded Hungary, showing what could happen to a German-allied regime that wouldn’t cooperate with Berlin’s demands. The Slovakian government ordered the Jews in the east of the country to go west, where Milan’s family lived. By August of that year, a Slovakian uprising against the country’s fascist puppet government had begun in earnest. The Germans finally invaded in order to put down the rebellion in the fall of 1944. That’s when the second major wave of deportations began, and an additional 13,500 Jews were shipped to the camps. Death squads and local collaborators murdered many others.

Abraham had gotten by with a fake name and a work permit. But as the Nazis entered the country, he knew he needed to go somewhere safe. He needed to disappear.

The Einsatzgruppe H paramilitary death squad was created in August 1944 to implement the Final Solution as rapidly as possible, including in Slovakia. It would end up committing the two largest massacres in Slovakian history, in Kremnička and Nemecká, killing thousands and arresting some 20,000 others between November 1944 and February of 1945. The Soviets found hundreds of mass graves as they liberated this relatively small country.

The Nazis got help from the Hlinka Guard, a Slovakian nationalist paramilitary group. They knew the country well and would go house to house, hunting for Jews and partisans. The local population was mostly hostile to Jews looking for safety, especially since both Slovak and Nazi propaganda blamed the Jews for the uprising and the resulting invasion. Some Jews hid in the mountains and starved that winter. In September, it was announced that anyone hiding Jews would be executed.

Martin Bartek, a friend of Milan’s family, was an engineer working in construction. He had traveled across the country to work on various projects, including a major rail line in the east. He was also a staunch anti-fascist and the patriarch of a rebellious family that orchestrated an underground railroad-like network that helped place a number of hidden Jews in homes in the region around Vadovce, the small town where Milan and his family lived. He had met Abraham while working on a railway viaduct in the eastern Slovakian town of Hanušovce nad Topľou, and decided to bring him west in hopes of finding him refuge.

Bartek was already hiding a Jewish family at his own home, so he took Abraham to his brother’s house in a town called Cachtice. This proved less than ideal, as Bartek’s brother had a radio and people would gather at his house to listen to news about the war. There were too many people passing through, and they worried someone would grow suspicious. Milan’s father, Jan, was approached to help figure out how to shelter Abraham. He could have easily done nothing. But something, perhaps his own rebellious nature, compelled him to say yes and take Abraham into his home.

The Nazis were already nearby, so Abraham had to be snuck into Jan and Milan’s house at night, through the forests and under cover of darkness. Stazka Hledkova, the daughter of another family involved in smuggling Jews to safety, brought him to the field behind Milan’s house, where Abraham crossed a stream to his new hideout.

The next day, he was working on the sawmill with Jan, who figured the fake cousin story would work for the time being. But the uprising was losing ground. Abraham needed to be hidden even more completely. Jan did away with the cover story and told his family the truth of who Abraham was. Instead of sending Abraham to certain death, they quickly built a lofted hiding spot in their barn for this total stranger.

Milan and his family were now outlaws. “At the time, we didn’t really think about why we were doing it,” he told me. But Milan and his parents agreed Abraham needed to be hidden, and they made the decision before conferring with Milan’s younger siblings. “It was on the radio and newspaper that if they discover some hidden Jews in your house, they would shoot the whole family,” Milan says. “It was very risky. People were afraid. I am not saying we were not afraid, but we were willing to take the risk to hide them as long as possible.”

Milan himself didn’t remember much hatred directed against Jews in his town before the war. When the fascists came, he said, you could hear propaganda on the radio. In Slovakia, there had always been the traditional religious antisemitism, the kind that blamed Jews for killing Christ. Throughout the 1930s, more recognizably modern forms of conspiratorial or racialized antisemitism spread rapidly, casting Jews as exploiters of the poorer Slovaks, as rapacious capitalists or bloodthirsty Bolsheviks, or as a fifth column more loyal to neighboring Hungary than to their own country. They were not “true” Slovakians, and politicians and others promised to confiscate their wealth. By 1938, long before the Nazis showed up, Slovakia had its own “Jewish Question” committee. The government demonized Jews, robbed them of their businesses and property, and fired them from government positions. Deadly pogroms convinced thousands of Jews to emigrate. In her book 999, which tells the story of the first all-female Jewish transport to Auschwitz, Heather Dune Macadams quotes a speech given by Slovakian President Jozef Tiso in August of 1942 as the deportations were in full swing. “People ask if what is happening now is Christian? Is it humane?” Tiso, also a Catholic priest, says to the crowd at a harvest festival:

Is it not just looting? But I ask: Is it not Christian when the Slovak nation wants to defeat an eternal enemy, the Jew? Is that not Christian? Loving thyself is a commandment of God, and that love commands me to remove everything that harms me, that threatens my life. And I believe nobody needs much convincing that the Slovak Jewish element has always been such a threat to our life, and I don’t think I need to convince anyone of that fact.

The speech was met with rousing applause. I add this not to indict modern-day Slovakia, but to put in context the type of people Milan and his family had to be. Everyone around them had been thoroughly conditioned to hate. It was not just the Nazi war machine. Jews had been demonized for years, all around them.

In his book about the sectarian tensions that tore apart Yugoslavia, Peter Maass recalls the warning a Bosnian man gave to him: “[W]hen the call of the wild comes, the bonds of civilization turn out to be surprisingly weak … The wild beast has not died. It proved itself a patient survivor, waiting in the long grass of history for the right moment to pounce.”

The first conflicts I reported on were brutal ethnic and religious wars in which entire societies were treated as the enemy. Throughout the 2010s, I traveled to Kurdish areas in Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, where conflict with ISIS or al-Qaida or the Assad regime was always on the doorstep and memories of Saddam Hussein’s genocide were still fresh. Young Kurdish men told me they were willing to die for their people’s freedom, and some of the ones I met did. Thousands of miles from the Middle East, outside the Rohingya concentration camps in Sittwe, Burma, Rakhine Buddhists told me it would be impossible to live next to their Muslim neighbors. Less than a year later, the Rohingya were targets of an even more violent ethnic cleansing campaign, classified as genocide by some organizations

A lot of the norms people in democratic countries believe to be durable facts of life can simply stop existing under the wrong conditions. Neighbors turn on neighbors. But war fosters other extremes. Recently I met Russians in Ukraine who had given up everything to fight along with Ukrainian soldiers to repel Putin’s invasion. I embedded with Sunni soldiers in Iraq who repeatedly faced death to liberate Christian and Yazidi villages, and interviewed young Buddhist activists in Burma who risked imprisonment to campaign and report on Rohingya persecution. They had all stood up to the madness around them despite the obvious and often deadly consequences.

Milan and his family were an anomaly, but there have been and will continue to be others out there like them, doing for others what the Huckos had done for my family.

Milan was born in 1931. A sister followed six years later, and a younger brother a year after that. The family struggled, and when he was barely a year old his mother, Eva, went to France to spend a few years working as a maid. Milan describes his youth as a simple peasant childhood. His father, Jan, was stubborn and uneducated, having come of age during the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But he was fair, principled, and had a natural distrust of authority. One night in a local pub in the early days of the war, the conversation turned to the Jews. The patrons were upset by the persecution, saying that if there were more people who were as disturbed as they were, this catastrophe wouldn’t be happening to the Jews.

Jan would have none of it. “You’re all saying you don’t like what’s happening, but it’s happening,” he shouted at them, drunker and bolder than usual. “So who’s letting it happen? Who?”

To young Milan, it was hard to grasp the gravity of the war. But in the midst of the German occupation, in a distant corner of Europe, it was tough for anyone to understand the true dimensions of the crisis. Some were convinced the Jews were only being shipped to Poland, and that they were building their own cities in their own territories, places similar to Native American reservations. “We didn’t know the consequences in the beginning, that people were being murdered and burned,” Milan claims. “Nobody knew it for a long time.”

Milan didn’t remember hearing much about the war until the uprising against the Nazis started in the summer of 1944. The partisans were operating in the woods close to the nearby Brezova and Myjava regions—Abraham’s brother, the only other member of his family who survived the war, was fighting alongside them.

At first, Abraham stayed in the loft above the barn, where he was well hidden but also capable of seeing out of holes in the exterior walls to keep a watch for German soldiers who conducted sweeps around the village. The family would sneak Abraham food, hiding it in what looked like dirty laundry. Any whisper, any hint, could have been a death sentence for all of them.

Months after Abraham arrived at the Huckos’ farm, two more Jews sent by the Bartek family arrived, Jan and Ladsilav Gros. Other members of the Gros family, including their parents, were hidden around the village. Milan and his family took to calling the hidden Jews “our boys.”

The winter of 1944 was brutally cold in Slovakia. The Nazis succeeded in gaining back ground from the Slovak partisans, although this only slowed the inevitable German defeat. Milan and his father spent every night for two weeks excavating a hidden cellar in the kitchen for the three men. Milan would stay up all night digging and then go to school the next day. The barn was becoming an increasingly risky hideout because the Germans were constantly pilfering supplies and food from the population they occupied. Eventually, Milan and the Gros boys moved into the cellar. But when spring came the melted snow flooded it, and the men had to be moved back to the barn.

Milan occasionally spent time with the hidden Jews. They would talk about the war, play chess, and discuss what they would do once the conflict ended. He brought them books, one of which was The Count of Monte Cristo, Alex Dumas’ novel about a man who keeps his spirit alive by plotting revenge during his wrongful imprisonment.

By the spring of 1945, the Third Reich was collapsing, and the Nazis were hunting down Jews more energetically than ever. After the Russians bombed nearby supply trains, the Germans went looking all over the village for horses to haul equipment and artillery back to the Czech Republic. Early one morning there was a knock on the door. It was a group of German soldiers demanding to be led to the barn, where Abraham and two Gros boys were sleeping.

If Jan was panicking, he hid it well. There were two locks on the door, one Jan could unlock and one on the inside that the hidden Jews kept bolted. Jan feared the soldiers would grow suspicious if he couldn’t get into his own barn. As he unlocked the door from the outside, Jan pretended he had left a key in the house. The Nazis followed him back to the house. One of the Gros boys caught on to what was happening outside. He slipped down from the loft, undid the bolt, and made his way back up to his hiding place. Jan came back, trailed by the Germans, and fidgeted a bit as he finally got the door open. The Nazis took the horses and left.

“There were some difficult and very sad days,” Milan wrote in testimony provided to Yad Vashem in 1992. “We were praying quite a lot, and asking God when everything [would be over]. Even now, after so many hours, I’m still crying when I’m writing this, and remembering old times. But we survived.”

At one point, Milan’s aunts came to the house and asked his father to send the hidden Jews away. Jan gathered his wife, Eva, and Milan and asked them what they should do. They agreed that they wouldn’t give the Jews up. Milan’s aunts didn’t visit again until after the war.

The war ended in May 1945. With the Nazis defeated, Slovakia in ruins, and most of their friends and family murdered, the Gros family went to Palestine, where another war was soon to begin. Abraham went back east with nothing and no one, although his brother had survived his time with the partisans. Abraham soon met Malvina, who had survived three years in the camps but had also lost everyone and everything. They married soon after and had my father, followed by two more children.

When my father, aunt and uncle were young children, they would ask why they didn’t have grandparents. The Nazis had killed three out of the four; the fourth had died before the war. So Abraham and his wife took them to see Jan and Eva Hucko, who the young children took to calling ‘grandpa’ and ‘grandma’. The families remained close for years. My grandmother last visited Milan only a year before she died in 2016.

Milan says that in their village there were four families who hid Jews. He thinks some of his neighbors must have known they were hiding people —“there were a lot more men’s clothes on the washing line,” he points out. There had only been one Jew in the village before the war, a man named Bron. He was taken to a concentration camp and never seen again. I asked Milan why he thinks others didn’t help, and he offered a simple explanation. “Fear. It was fear, I think. Fear is equal to death,” he says. “Maybe if we had thought about it more, fear would overwhelm us.”

Milan tried not to think about the war too much. He’s old, he said. His mind wanders. Things got lost in translation with some of my questions. Details were occasionally hard to recall. Pieces of the story of my grandfather’s rescue were already gone. He started to cry at times, his daughter glancing at me from across the room. Be gentle, she had said. Don’t push too much.

As the interview finished, he showed me some photos of his old schoolmates, of his family, of our families together just a decade or so after the war. He held up the medal he received in Bratislava in 1992 after he was honored as a Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem.

I asked him: What should I tell my children one day about what he did? He replied: “Just what happened. Your grandfather was saved in Vadovce, together with others. It was good that such people were there [to save him] and it’s important that such people are here in the future. But the best would be if such things would never happen again.”

Later, he told me, “I think that, essentially, man is not evil. Something will make him a bad person. There must be some impulse, but it’s difficult to say. People were able to do such things … it’s difficult for me to explain.”

I sat down for a last conversation with my grandmother shortly before she died in 2016. I already knew the details of her survival during the Holocaust: the three years in the camps, the death marches, the Mengele examination. She had spoken openly about everything, recording hourslong interviews for various remembrance projects. By this point, I had also been covering conflict for years. Although I often reported on actual combat, I had grown fascinated by how and whether the victims of war could ever move forward with their lives after the fighting stopped

There would be no real answer forthcoming from my grandmother. There was no secret method for continuing to live after Auschwitz. She just did, she said. She didn’t have a choice.

Milan had told me something similar—that he didn’t have a choice but to act the way he had. There was no deep answer. My grandmother and Milan were not people who had fortuitously discovered some clear meaning in their suffering. Surviving, and helping others survive, had been enough. They just did.

Perhaps “why?” is a question that can only be asked by a person living a safe life in a peaceful country. Caught up in the deadliest conflict in human history, Milan didn’t look for a deeper meaning, or for something that set him and his family apart. They were a little rebellious. They knew right from wrong. They had a sense of injustice. That was all it took.

A few days later, before I left Slovakia, I went to see Milan again at his apartment in a nondescript housing block. Teenage girls walked by playing American hip-hop on a loud portable speaker. Milan’s wife had passed away, and his apartment was a shrine to her. He was thrilled to have us visit him at home. He made tea and put out a plate of cookies. As we talked, I wondered if I would ever see him again, if I would ever have children that would meet his children.

Unfortunately, I wouldn’t get the chance. Milan died in January 2021, and with him my last personal connection to the Holocaust. I had more questions for him, but I don’t think his answers could possibly have explained everything.

Milan and his father did what they did because it was the right thing to do. They did it because they thought what was happening around them was wrong. On a collective level, that sense of justice can come far too late, and sometimes not at all, as I’ve seen in my own reporting. But individually, an offended sense of justice may be the best you can hope for. Fortunately for my grandfather, it was all that he needed.

“A man must be a man to another man,” Milan’s father had told him. “Not a wolf.”

Danny Gold (@dgisserious) is a journalist and documentary filmmaker who covers conflict and crime. He also makes The Underworld Podcast.