Reading Origen in Jerusalem

A collection of 29 recently discovered homilies by the early Church Father offers dazzling insight into a shared late antique universe of Christians and Jews

In 1934, the Yiddish writer Sholem Asch published Der T’hilim Yid (literally: “The Psalms’ Jew”; published under the title Salvation in English). Yet as my Paris high school teacher Emmanuel Levinas used to tell us, the Psalms “belonged” at least as much to the Christians as to the Jews. A Litvak, he was wary of Hasidic romanticism, arguing that it is mainly in the company of the Talmud, rather than of the Psalms, that Jews should live.

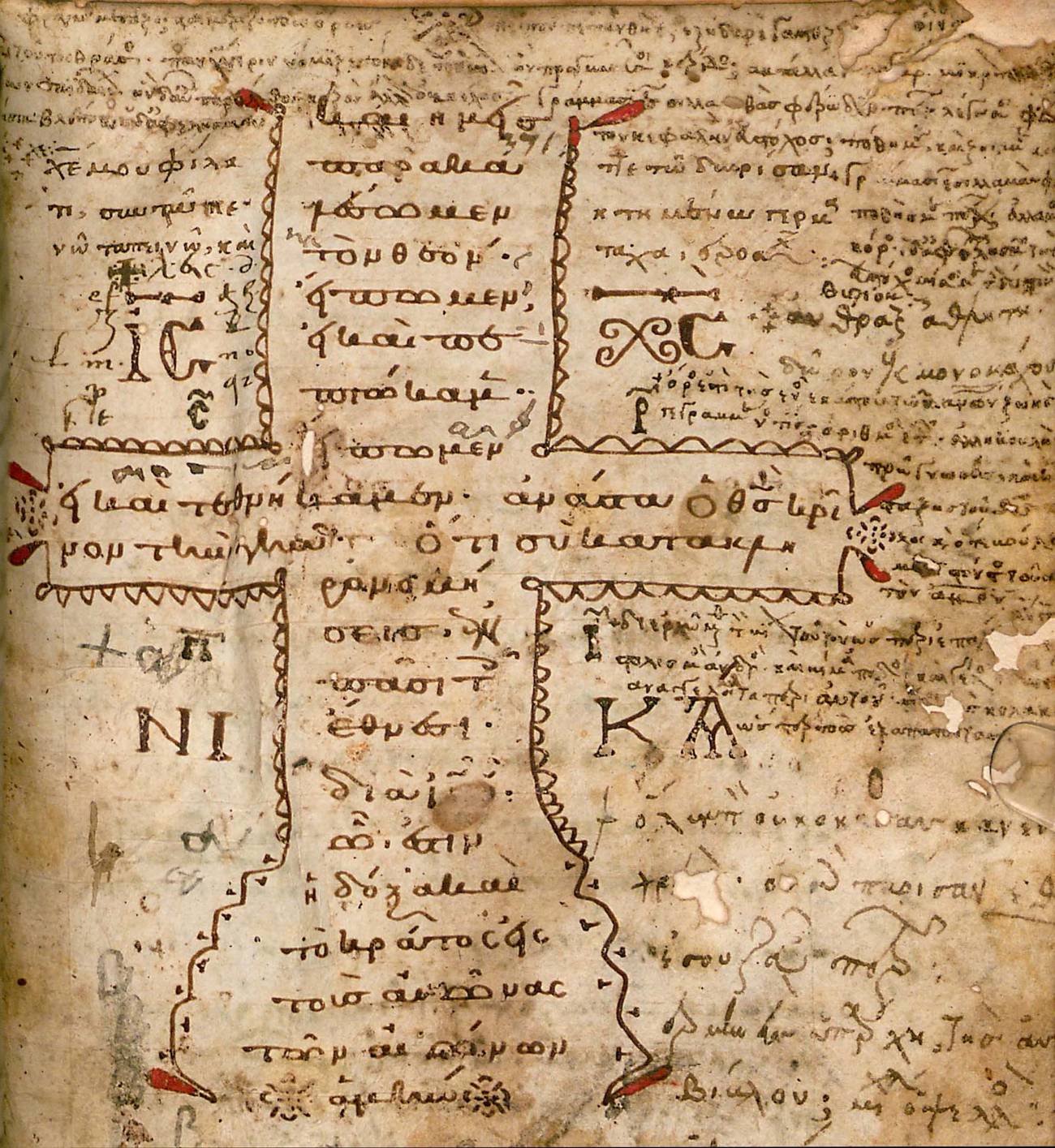

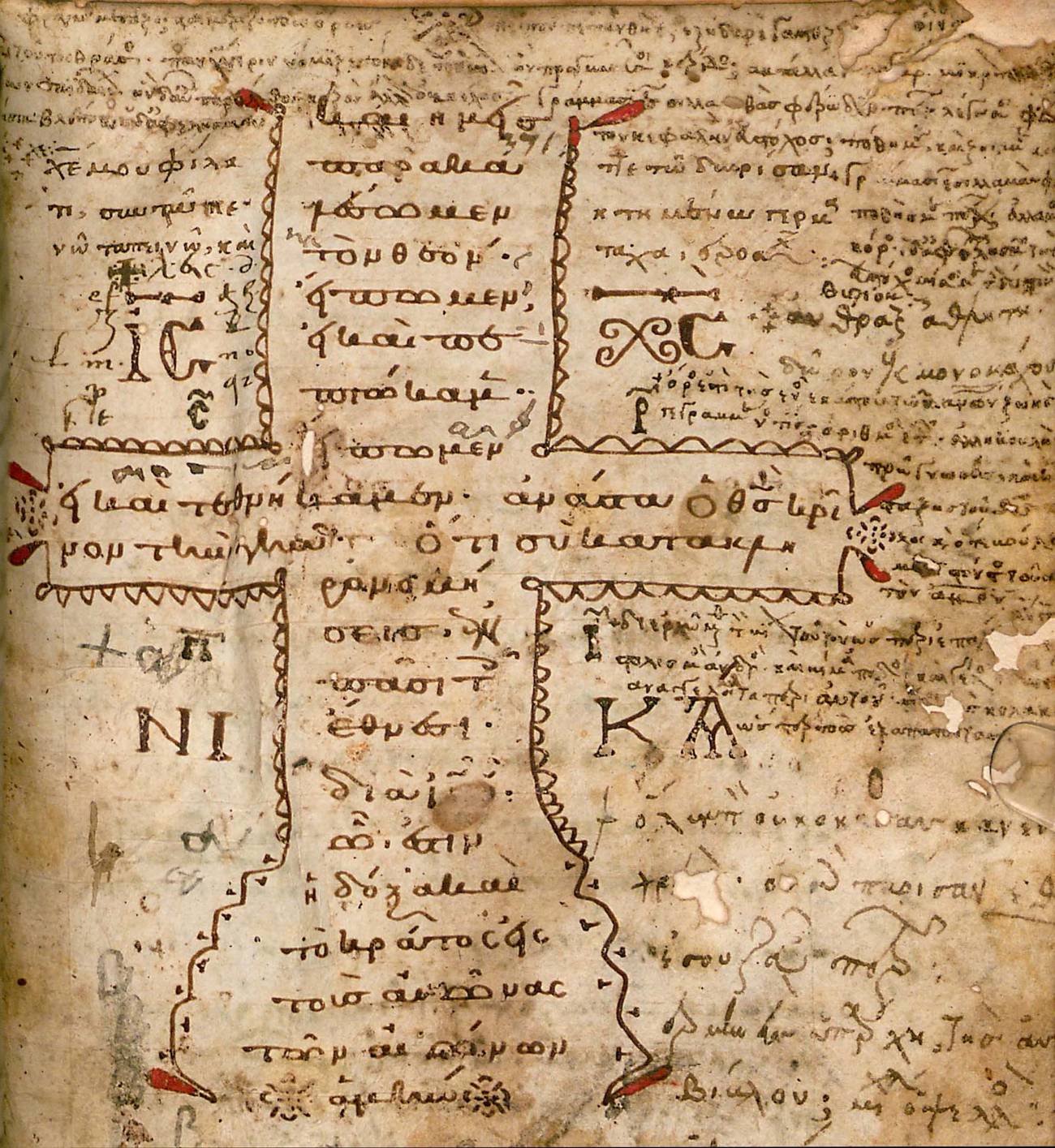

The unique significance of the book of Psalms for the Christians, and in particular in Christian prayer and liturgy as well as for the Christian theologians, has recently been highlighted anew thanks to the 2012 discovery (in the Bavarian State Library in Munich) of 29 new homilies on Psalms by Origen, in a 12th-century manuscript. These homilies, which constitute the largest collection of early Christian preaching before the fourth century, have now been published in the original Greek by the Italian scholar Lorenzo Perrone, as well as translated into English by the American scholar Joseph Trigg. The new discovery echoes, in a sense, those of important collections of Augustine’s letters and sermons, discovered respectively in libraries in Paris (1975) and in Erfurt (2007). The new homilies represent an important new source permitting a richer, more precise understanding of the status of Psalms in early Christian literature and piety.

Origen (circa 184-circa 253) stands out among the Church Fathers as a highly original thinker who may be compared to Augustine, being the great Latin Father’s only serious contender for similar prominent fame in the Greek East. Origen was born and grew up in Alexandria, the second-largest city in the empire. In or around 231, he moved to Caesarea Maritima, the administrative capital of Roman Palestine, a much smaller town, of little cultural significance. He died a martyr, from the sequels of torture, that he suffered in Tyr as a Christian. While the great Egyptian metropolis was the locus of his Christian and philosophical education, as well as of his early theological works, most of his writings (in particular his biblical commentaries and his sermons) were written in Caesarea.

Origen’s intellectual achievements and audacity would earn him a very long, if highly contentious, afterlife. In 553, the Council of Constantinople anathemized a number of his theological theses, a condemnation that prevented many of his works from surviving in the original Greek. It was only in the 20th century, mainly thanks to the endeavors of the Jesuit Father (and future Cardinal) Henri de Lubac, during and after the Second World War, that interest in Origen was rekindled.

The Psalms remained a challenge for Origen throughout his life, having a pervasive impact on his thought. He started preaching and commenting upon them early, until his last years, when the new homilies were written. More precisely, the Psalms constantly remained the fuel, as it were, not only of Origen’s life in prayer, but also of his reflection on prayer in idea and practice.

Origen’s move to Palestine (the biblical land, which only in the next century would become known among Christians as terra sancta) represents the major turn in his life. His Palestinian years, which are much better known than his youth, were also his most productive—and the new homilies represent the final intellectual product of those adult years.

In order to fully understand Origen’s thought, one must reckon with the various dimensions of his intellectual world—a galaxy of religious and intellectual identities, of thought and behavior patterns. As a Christian, Origen felt first of all challenged, in Alexandria, by dualist heretics, Gnostics, and Marcionites alike. He had been educated in an intellectual world in which Platonism was the leading trend. Twenty years older than Plotinus, he could not have studied with him, but he was certainly immersed in the same milieu in which Plotinus first developed his own interpretation of Plato’s thought. Moreover, the young Origen was in contact with a number of Jews (he mentions “the Hebrew,” perhaps a Jewish-Christian from Palestine), who were, in Alexandria, the inheritors of Philo’s method of biblical interpretation. When he moved to Caesarea, Origen met Palestinian-educated Jews, in particular from Rabbi Abbahu’s beit midrash, although (like Augustine, but unlike Jerome) he never managed to master Hebrew.

The new homilies add many valuable precisions to our knowledge of Origen’s standing at the confluence of diverse social, ethnic, cultural, intellectual, and religious worlds. In particular, they sharpen our understanding of Origen’s perception of Jews and Judaism. Origen conversed with Hellenistic Jews in Alexandria, with Palestinian rabbis in Caesarea, and also, in both places, it seems, with Jewish-Christians, such as the Ebionites (from the Hebrew word evion, poor, common in Psalms, poverty having become a spiritual goal among ascetic Jews).

These Jewish-Christians, as they are usually called, were Jews who believed in Jesus’ Messiahship while retaining their Jewish identity and ritual praxis. Origen met, as well, with Jewish converts to Christianity. With them all, he conversed in Greek (the new homilies confirm that in Caesarea, the rabbis knew more Greek than previously suspected. Jewish scholars were able to inform him on what was of primary importance to him for a correct understanding of the Scriptures: Jewish biblical hermeneutics.

Like all Christians, Origen was convinced that the Jews were wrong in rejecting Jesus as the Messiah announced by the Hebrew prophets—a lethal sin which brought upon the Jews the divine punishments of the destruction of their Temple and exile from their land. But he also believed that the Jews, thanks to their knowledge of Hebrew, possessed the keys to the full and adequate understanding of the biblical text, which they read in the original, something that often eluded Christians who could only read the Scriptures in translation.

To be more precise, Origen’s fundamental ambivalence toward Judaism and the Jews counterposed a Jewish esoteric interpretive tradition—which also became the deeper, or secret Christian tradition—to rabbinic Judaism, which reflected Jewish rejection of Jesus and blindness to the true meaning of Scripture. All in all, it must be emphasized that Origen’s polemic against Judaism and the Jews remains free from prejudice and vicious overtones, too often fueled by lack of knowledge.

A major example of the crucial contribution of Origen to a better understanding of the late complex, late antique interface between Judaism and Christianity may be found in his Homilies on the Song of Songs. This work, which has survived only in Jerome’s Latin translation, played a major formative role in the fashioning of Christian mysticism, throughout the Middle Ages, and beyond. One may say that this text is at the root of later Christian mystical literature in the West, as exemplified in the following passage:

God is my witness that I have often perceived the Bridegroom drawing near me and being most intensely present with me (Saepe, Deus testis est, sponsum mihi aduentare conspexi et mecum esse quam plurimum); then suddenly He has withdrawn and I could not find Him, though I sought to do so. I long, therefore, for Him to come again, and sometimes He does so. Then, when He has appeared and I lay hold of Him, He slips away once more; and, when He has so slipped away, my search for Him begins anew.

The personal experience described here by Origen is striking; it represents as has been noted by Dom Rousseau, the translator of this work, a rare depiction of mystical experience in the whole of Patristic literature. Although it does not explicitly refer to a union (henosis) with God, a striking parallel is offered in a famous passage in Porphyry’s Life of Plotinus (23):

To Plotinus “the goal ever near was shown”: for his end and goal was to be united to, to approach the God who is over all things (to enōthēnai kai pelasai tōi epi pasi theōi). Four times while I was with him he attained that goal, in an unspeakable actuality and not in potency only.

Inter alia, Origen is therefore our very first witness to the role of the Song of Songs in Jewish mysticism. In the prologue to his Commentary on the Song of Songs, Origen claims that according to the rabbis, this last text, which is endowed with an esoteric meaning, should be read only by mature persons (nisi quis ad aetatem perfectam maturamque pervenit). The same is true of the first chapters of Genesis, which deal with the creation of the world, as well as the first and last chapters of Ezekiel, which discuss, respectively, the divine chariot and the Temple. What mostly counts here is Origen’s quite precise awareness of the parameters of esoteric rabbinic biblical hermeneutics. Although he did acquire some knowledge of Jewish traditions already in Alexandria, it is doubtless in Caesarea that he encountered Jewish biblical exegesis in a more sustained manner.

One of Origen’s most important testimonies about Jewish esoteric hermeneutics of the biblical texts is extant in the Greek original, but only as copied in the Philocalia. In this text, whose literary power evokes Kafka’s, Origen starts by noting that the Scriptures are locked and sealed. They are full of enigmas, parables, dark sayings hard to understand. He then repeats a “beautiful tradition” which he received “from the Hebrew”—a mysterious figure who may well have been a Jewish Christian from Alexandria, and who appears a number of times in Origen’s writings. According to this man, it is precisely their lack of clarity which shows that the Scriptures are divinely inspired. They resemble a large number of locked doors within a single house. A key is present on each door, but it cannot open it. The interpreter’s role is to find, for each door, the right key. The Scriptures’ interpretive principle, in other words, is scattered among them.

For Origen, like for the whole Patristic tradition, contemporary Jews, inheritors of the Pharisees, having a veil in front of their eyes, are unable to understand their own Scriptures correctly. They have lost the ability to find the right key opening each door in the large scriptural mansion. But for him, too, true Christianity is identical to secret Judaism, a secret tradition better conserved within Christianity than among the rabbis. Hence, the Hebrew esoteric traditions are equivalent to the spiritual interpretation of the Church, or more precisely, of true Christianity.

Since Newton, mathematicians, and physicists alike have been fascinated with the “Three-Body-Problem,” for which no general, analytic solution exists: A problem that can be solved relatively easily when two bodies are in play becomes unsolvable as soon as a third body enters the game. The scholarly traditional search for literary sources is predicated upon the often utopic assumption of a single trajectory of ideas, which may be followed back through time, as it were. These few texts of Origen illustrate the fact that when dealing with sources, or with the origin of concepts and trends, we end up with a whirlpool of ideas in perpetual movement, and constantly transforming themselves and one another. In the Roman Empire, philosophers, Christians, and Jews were in a constant, fruitful exchange of ideas.

Disappointment with the search for ultimate origins has kindled a recent trend in scholarship which insists on a synchronic vision of things, with a distressing, unnecessary consequence: giving up on diachrony itself. Like history itself, the history of ideas remains overdetermined: We are at once, and perforce, both Greeks and Jews, as Borges claimed. Origen is probably the major figure at the late antique interface between philosophers, Christians, and Jews who incarnates this reality, as demonstrated afresh by his newly discovered homilies.

Guy G. Stroumsa is Martin Buber Professor Emeritus of Comparative Religion, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Professor Emeritus of the Study of the Abrahamic Religions, and Emeritus Fellow of Lady Margaret Hall, University of Oxford