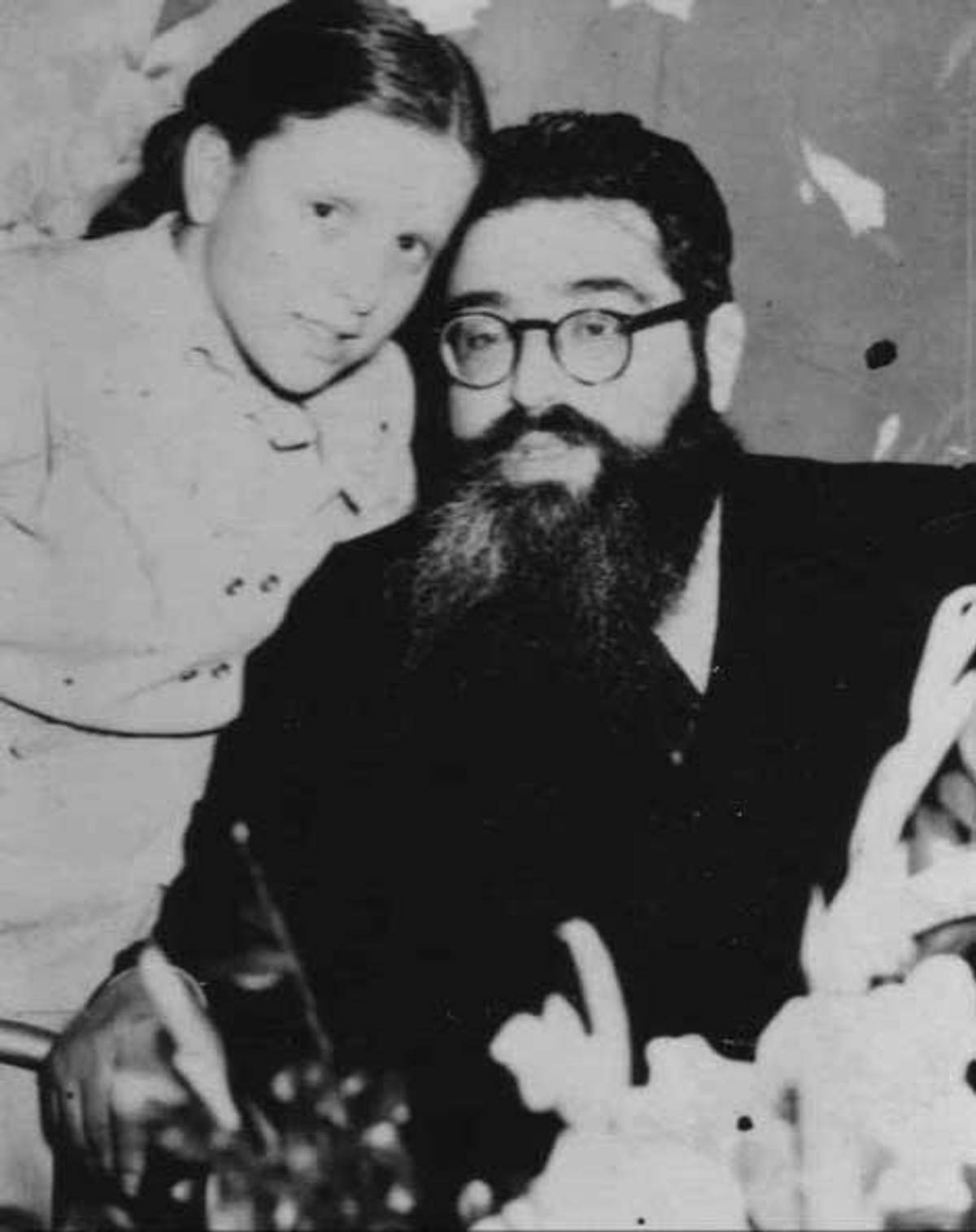

Rebbetzin Bruria Hutner David, 1938–2023

A former student remembers the blazing intellect who revolutionized Haredi women’s education

If people know of Rebbetzin Bruria Hutner David, who passed away in Jerusalem on April 9, but did not know her, they probably know two things about her: that she played an important role in the production of her father, Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner’s, masterwork, Pachad Yitzchak, and that she earned a Ph.D. from Columbia University. Both of these facts of her biography have been retold often, frequently by those who imagine that they are relaying the frisson of a gotcha or perhaps conveying a note of hidden feminism: The scion of rabbinic royalty, born in New York City in 1938, was a learned woman in ways both secular and religious, which she did not trumpet or demand credit for. But as a way of praising her or summarizing her life’s accomplishments, it fails, for it defines her on others’ terms. Others, often men, may have been impressed primarily by her contribution to her father’s Torah work, or her academic doctorate. But that was likely because they either did not know of, or did not respect, the bold undertaking in Haredi women’s education that was her life’s work.

That work was a project that, when described, sounds audacious, if not fanciful. From one institution based in the Matersdorf neighborhood of Jerusalem, she hoped to rearrange the mental furniture of Haredi women chosen for their academic ability and their willingness to have their mental furniture rearranged. Thus equipped, these women would go on to be the teachers and rebbetzins and mentors and mothers who would reshape American Haredi Jewry to become more formal, more dignified, more aware of the uniqueness and incomparable worth of Torah (as well as more proud of its distinctiveness), less acculturated, and less, well, American.

To look back after 50 years of the institution’s life is to see, remarkably, how much of her vision she realized.

The institution was Beth Jacob of Jerusalem—BJJ, as it was known to everyone but Rebbetzin David, or “the Machon,” as she insisted on calling it. It began as an arm for foreign-born students of a large and venerable Jerusalem Bais Yaakov school, and in its later years became a free-standing institution for students from outside Israel. When I attended in 1994-95, we were American (mostly), Canadian, Australian, British, French, Swiss, Belgian, and South African.

The admissions process was frankly elitist. In her institution’s heyday, Rebbetzin David skimmed the intellectual cream off of the top of every non-Hasidic Bais Yaakov high school class. In later years, as the “seminary” (Israel gap year for women) experience became extremely widespread, and many institutions opened to meet the demand, there were other schools geared toward intellectually gifted and academically inclined women, some of which offered more engaging modes of instruction or younger and more vibrant educators. While she was brilliant, rigorously intellectual, and a demanding teacher, Rebbetzin David’s goal was not primarily to teach material or sharpen skills. She was out to inculcate a worldview. If ever the German word Weltanschauung, overused in a certain sector of the modern Orthodox world, was apposite, it is here.

Someone asked me if there was a website where they could read Rebbetzin David’s Torah thoughts. Every word of the question indicates how profoundly the questioner did not know Rebbetzin David or her ethos. She never taught or wrote for any audience other than her own students. She did not lecture publicly; she addressed current students and alumnae. To frame this as “tzniut,” perhaps the most highly praised virtue for a Haredi woman, seems to me to miss the mark. I reached for, and then set aside, the obvious metaphor of casting pearls before swine, since Rebbetzin David would have recoiled at its coarseness and its non-Jewishness, but she was not about to lay out her ideas to audiences unprepared to appreciate and absorb them. She was not offering drive-by entertainment or one-off inspiration. (This aversion to providing entertainment was manifest in BJJ’s classes, as well, most of which were conducted as dry frontal lectures.) She was imparting and reinforcing a worldview, and she would and could do so only to those who had already shown a willingness to listen. Nor would she have taken credit for even a scintilla of novelty in her approach—she saw herself as transmitting an authentic worldview, as expressed in a wide range of Torah sources and crystallized in the teaching of “the Rosh Yeshiva,” as she always referred to her father.

In a conversation after her passing, I was asked, “was one school year enough to achieve that? September to June?” The answer is both yes and not really. That year was a beginning, a challenge, a shift, which some students resisted, some students sidestepped, and some ignored. But for the ones who embraced her example, her teaching carved an indelible groove, one that could be reinforced—through alumnae shiurim, letters and conversations, newsletters and visits—over the years and decades.

Rebbetzin David’s worldview emphasized the primacy of Torah—not in the reductive way of “you should marry a man in kollel,” but in the underlying philosophical way that means that whatever field of study or profession her students pursued, it would be with a deep understanding of the way that the Torah’s wisdom is incomparable to the wisdom of any discipline or academic endeavor. Whether that teaching ended up shaping her students’ or their husbands’ life choices, it would shape how they spoke, how they thought, whom they admired, and which accomplishments they most highly praised. (That question—whom do you admire? What do you praise?—was a characteristic one, and one she returned to often. “Ish lefi mehallelo.”)

The deep sense of the fundamental soul-difference between Jews and non-Jews that she sought to instill may not sit well with everyone reading this, but it was a core element of her teaching. She taught this sense of difference in ways halachic, philosophical, and cultural. We were meant to understand our distinctiveness, our apartness even from the most refined and ethical non-Jews. She wanted us to feel less identified in every way with the surrounding world, and she praised to her American students the European students who felt less emotionally connected to the countries of their birth and citizenship.

Rebbetzin David sought to have us live and move through the world with a dignity and weightiness born of our essential importance as human beings and as Jews.

Rebbetzin David sought to have us live and move through the world with a dignity and weightiness born of our essential importance as human beings and as Jews. She abhorred silliness and meaninglessness. Relaxation, or regeneration, certainly. But being silly? Life was meant to be lived with seriousness of purpose.

Her teaching was buttressed by a stream of supports and examples that ranged widely: citations from a broad array of Torah sources, as well as citations from contemporary newspapers and books and instances from prevailing culture. She kept abreast of American newspapers and was well-read in contemporary academic literature in both Israel and the United States.

While she admired, enjoyed, and was drawn to raw processing power, intellect was not ultimately granted for its own sake, or to enable parlor tricks. Above all, she cited a dictum that began as a narrow halachic statement about the placement of the Ata chonantanu prayer in maariv on Saturday night but that she took as a mission statement for life: “Im ein da’at, havdala minayin?” "Without discerning intellect, how can one make distinctions?” Those distinctions—between the holy and the mundane, between different gradations of holiness or importance—were characteristic of everything about her teaching and her ethos.

Ultimately, her project was to ensure that her students imbibed and propagated certain values—that they held a worldview not by osmosis or knee-jerk cultural reflex, but by deep understanding of the underlying values it encoded. Whether those values were holding oneself apart from the surrounding culture, or a rejection of starry-eyed enthrallment with the Zionist state, she wanted us to do that not merely because it was what our community did, but because we understood that it was a reflection of a Torah approach to life.

Her teaching was what we knew of her. She was not otherwise emotionally open or available to her students; she did not invite us into her private life (metaphorically) or, generally, her home (literally). She retained her father’s apartment down the street from the BJJ dorm and it was there, rather than in the home she lived in with her husband in the Har Nof neighborhood, that she held smaller and more intimate gatherings of students. Certainly, she never shared personal tales of her family life or her interior emotional life.

In the hands of her detractors, and those who did not know her, it was easy to tell a story that turned her intellectual brilliance and emotional reserve into a cautionary tale. That she never had children contributed to a narrative that sounded like nothing so much as 19th-century warnings that excessive intellectual exertions by women would divert blood flow from their uteruses to their brains. Those of us who knew her in any capacity knew her to be a woman of passionate emotion, powerfully expressed. She loved her students, and reveled in Torah learning, and expressed strong and fiery feelings about matters of importance to her. (She did not, as no one reading this will be surprised to learn, suffer fools lightly.)

And me? I’m a modern Orthodox feminist—and one of the ones, ironically, who was deeply shaped and influenced by my interactions with Rebbetzin David, even if not all of her lessons quite took. She encouraged me to engage less seriously in the secular academic world, concerned about how I might be drawn to it if fully immersed in it. I immersed myself and was drawn, pursued an academic Ph.D., and came to think differently than she did about many things. I still value the many lessons I learned from her, and the ways in which continuing to learn from her was a challenge to my worldview, even as I did not abandon it to reembrace hers.

My last substantive conversation with her was one in which I tried to explain how my worldview differed from hers—how I saw the relationship between secular knowledge and Torah differently than she did. Fascinatingly, her response was not to criticize me, but to attempt to convince me that our views were not so different, after all. I see that, now, as an expression of love. She was a brilliant woman, and entirely capable of understanding what I was saying. But she was trying to convince—me? herself?—that we were not so far apart. I think much more now about her emotional life—the years of guiding students through dilemmas of child-rearing and education when she never had any children of her own; of investing her soul-energy in students who, much as we loved her, could never feel toward her as she felt toward us (as students never can toward teachers, nor children to parents.) I think about how relatively young she was when she taught me. I saw her as being as old as the hills, but she was in her mid-50s, only a decade older than I am now.

Rebbetzin David was a blazing intellect, who inspired her students with her rigor and range even as she discouraged us from pursuing the credentials she amassed. She was deeply private and reserved, and she loved her students, and we loved her. She inculcated in her students a deeply traditional worldview, even as in some ways she lived her life outside of the narrowest lines of her community. She was a woman of great complexity, living out her values with thoughtfulness and intention. She had no children, yet she left thousands of students shaped by her teaching and determined to pass it on. It is easy, and incorrect, to see her as a woman of contradictions, even hypocrisy. She was, instead, a woman who lived what she taught: that the work of a great intellect is to make careful distinctions.

Rivka Press Schwartz teaches history and serves as Associate Principal, General Studies at SAR High School. She also serves on the faculty of the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America.