Separating Pearls From Sand

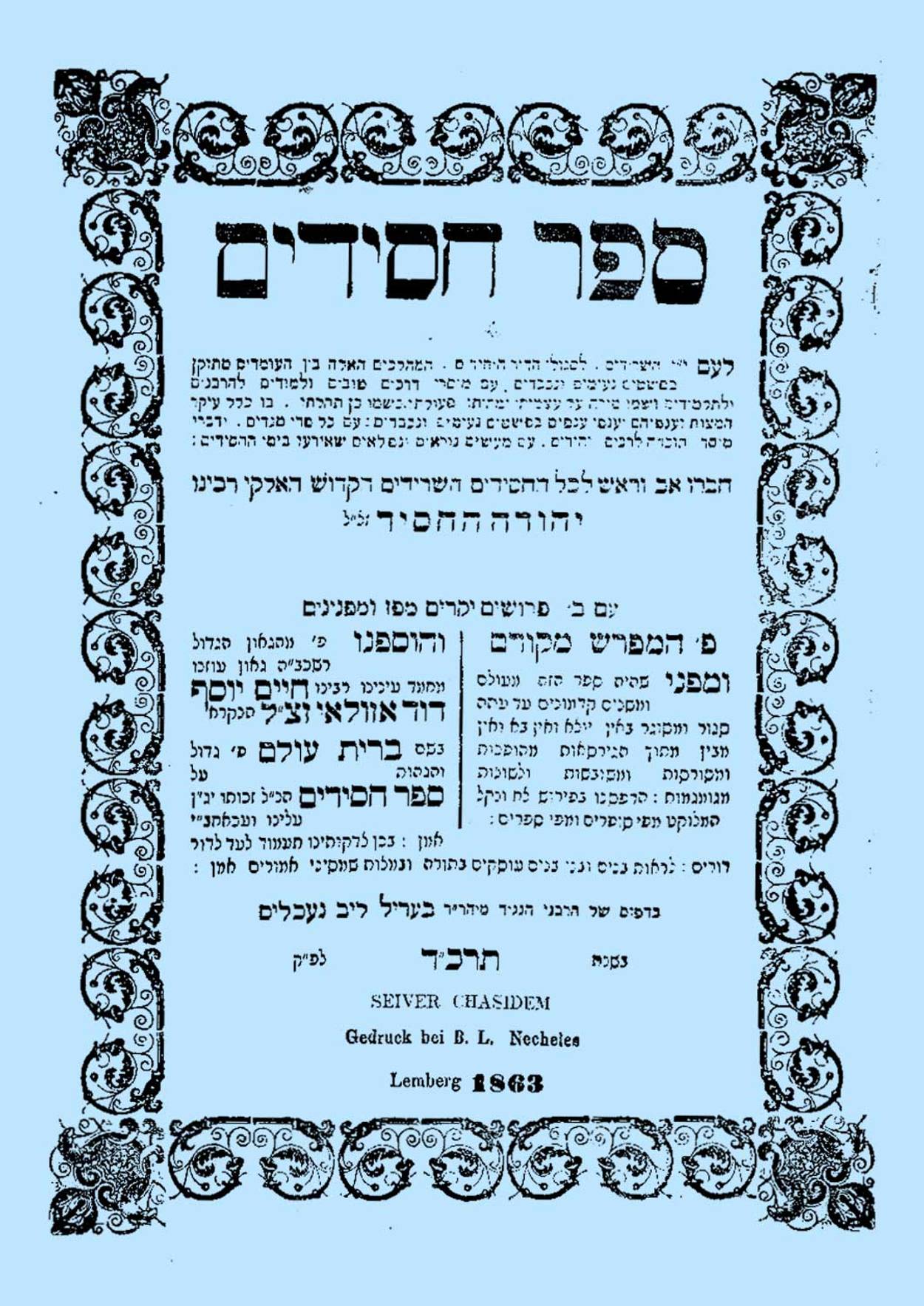

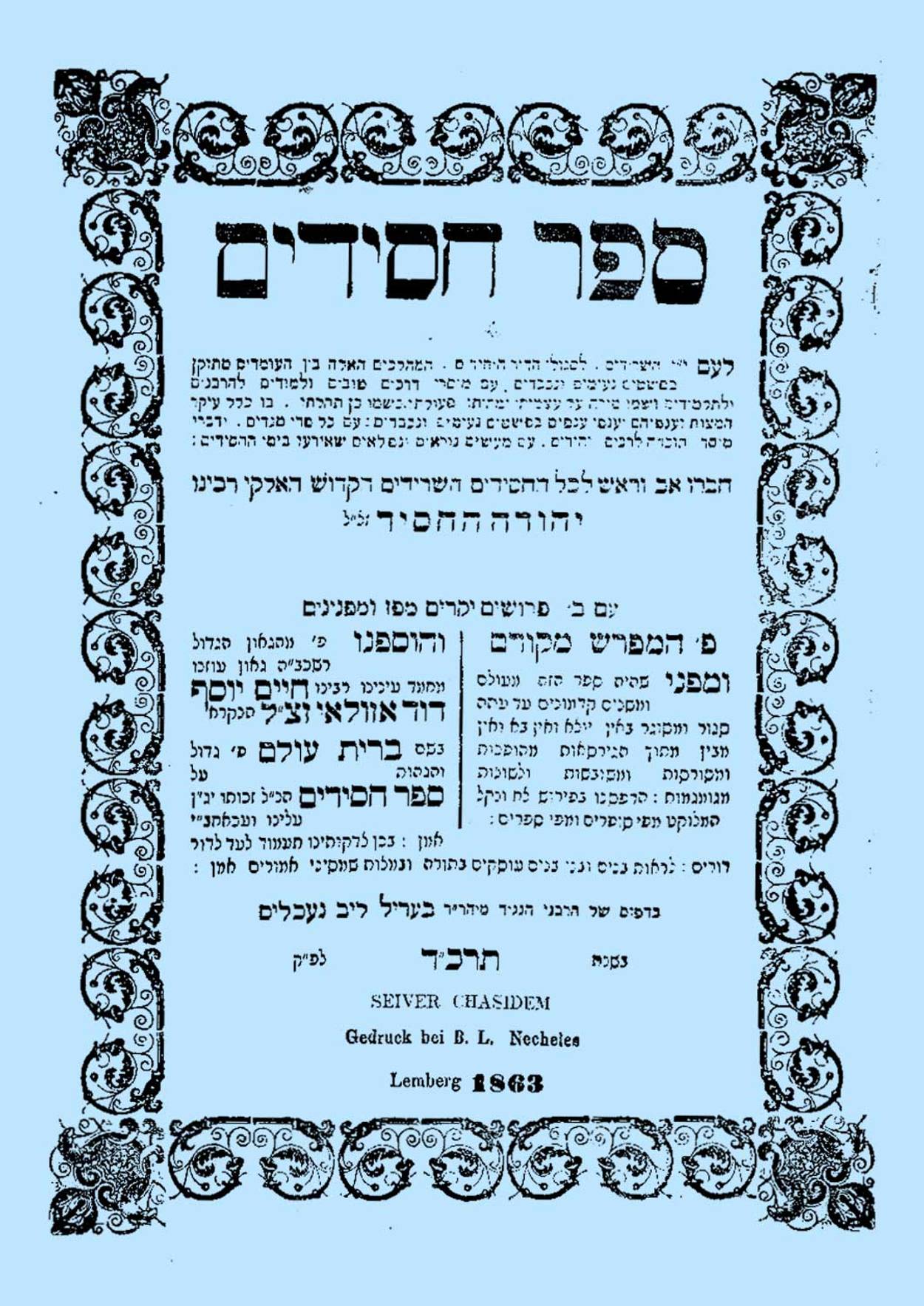

The status of stories in Sefer Hasidim, one of the most reprinted Jewish books

Jacob ben Isaac Luzzatto’s second introduction to the second printed edition of Sefer Hasidim emphasized both the Jewish people’s particularity and the significance of the commandments. “We must praise the God of Israel,” Luzzatto began, and then quoted Hasdai Crescas (as rendered in Roslyn Weiss’ new translation of Crescas’ The Light of the Lord):

In the magnitude of His kindness and the abundance of His goodness, God was provident over all from the realm of His abode, and chose the house of Jacob in whose midst to rest His glory, that they [the Israelites] might love and be in awe of Him, serve Him, and cleave unto Him. For to live thus is the pinnacle of human happiness, in pursuit of which many have become perplexed and have walked in darkness, to prepare the way for us, the way of life, a way that would be so very distant without them—Who could find it?—unless there shone upon it the true light that is called ‘the radiance of the Divine Presence.’

Jews expressed their love for God, united with God, and attained perfection and immortality by enacting the commandments. For Luzzatto, Sefer Hasidim represented an access point through which Jews could reacquaint themselves with the meaning of the commandments, learn to love and serve God, and thereby acquire their transcendent reward. Within its pages, those commandments were distilled down to their essence. Sefer Hasidim, Luzzatto wrote,

includes the root of the commandments and their branches and the branches of their branches in straightforward explanations, pleasant and honorable, with every luscious fruit [Song of Songs 4:13], and ethical teachings and rebuke for the collective and the individual. With awe-inspiring and marvelous tales that happened in the days of the pious ones.

According to the description, Sefer Hasidim comprised the two essential genres of rabbinic literature: Halacha (law or “the commandments”) and Aggada (lore or “awe-inspiring and marvelous tales”). It combined normative and narrative elements, with the lore intended to evoke religious devotion. For Luzzatto, Sefer Hasidim served not only as a religious guide but also as a “scroll of secrets” (megilat s’tarim) in the tradition of rabbinic Judaism. This designation referred to a canonical text that was initially transmitted orally but later written down during times of persecution to prevent its loss.

Luzzatto quoted Crescas to explain the origin story of Judaism’s concept of Scripture, distinguishing between the Written Torah (Hebrew Bible) and the Oral Torah (rabbinic literature). According to Crescas, the Oral Torah was initially transmitted orally but eventually written down due to the rise of troubles and forgetfulness among the Jewish people. Luzzatto emphasized that Sefer Hasidim could help Jews regain their religious commitments and uniqueness among the nations by offering guidance and reminding them of what had been forgotten in tumultuous times.

Luzzatto further asserted that Sefer Hasidim held a canonical status akin to other great works of rabbinic tradition. He compared it to the stone tablets of the biblical covenant, claiming that reading a portion of Sefer Hasidim daily fulfilled a lifelong obligation. Luzzatto’s analogy suggested that he regarded Sefer Hasidim as part of the Jewish canon, alongside the Written Torah, Mishna, and Talmud, deserving ongoing interpretation.

In describing Sefer Hasidim as a “secret scroll,” Luzzatto drew parallels to the claims made about Kabbalah during the medieval and early modern periods. Just like Kabbalah, Sefer Hasidim was seen as a corpus of orally transmitted traditions that were eventually committed to writing to prevent their loss. Luzzatto’s assertion aligned with the debates surrounding the printing and circulation of kabbalistic texts, with some arguing for their dissemination in the face of persecution. Luzzatto believed that Sefer Hasidim, like the works of Kabbalah, had a place in the Jewish canon alongside other printed rabbinic and kabbalistic works.

While Luzzatto wrote that Sefer Hasidim contained both Halacha and Aggada, he was particularly interested in its Aggada and highlighted its relevance for readers in his second introduction. Since antiquity, rabbinic tradition generally understood that the Oral Torah was composed of both Halacha and Aggada, with the latter encompassing tales, homilies, exegesis, and historical accounts from antiquity. Although the Talmud and other works intermingled these genres, the yeshivah curriculum, as it developed, primarily focused on training students in the explication of Halacha while relegating Aggada to the sidelines.

In the 16th century, some scholars sought to restore balance and emphasize the importance of Aggada. One prominent figure was the Spanish exile Rabbi Jacob ibn Habib (1460-1516), who authored the compendium of Aggada and commentary called Ein Ya’akov (1516). Jacob believed that Aggada provided spiritual nourishment necessary for Jews to resist the temptations of philosophy. Similarly, the Maharal of Prague (Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, d. 1609) regarded Aggada as a source of esoteric wisdom and wrote two books elucidating aggadic passages from the Babylonian Talmud. In contrast, Azariah de’ Rossi (1511-1578), in his magnum opus Me’or Einayim (1573-1575), took a dismissive stance toward Aggada.

In the 16th century, Christian missionaries and polemicists began to highlight Aggada as evidence of Jewish ignorance and foolishness. They cited passages like the story from the Babylonian Talmud (Gittin 56b) about a gnat causing Roman Emperor Titus to go mad. Christian critics used such stories to reinforce their belief that Jews were destined to remain benighted. In response, Azariah de’ Rossi sought to neutralize these attacks by denying the Aggada any normative or historical value. He regarded it as a source of moral teachings and entertainment, but not as truth.

Contrasting de’ Rossi’s perspective, Luzzatto, like Ibn Habib, believed that Aggada could provide spiritual comfort and strengthen Jewish religious commitment. His work, Kavvanot ha-aggadot, served as a companion volume to Ibn Habib’s Ein Ya’akov. It featured digestlike explanations of aggadic passages from the Babylonian Talmud, along with Luzzatto’s allegorical commentaries and cross-references to other works, including Sefer Hasidim. Luzzatto argued that with Kavvanot ha-aggadot in hand, Jewish students would grasp the true hidden meaning of the Torah (sodot or sitrei Torah) and the root of faith (shoresh ha-emuna). He juxtaposed Aggadot from various sources, including the newly printed Zohar and Sefer Hasidim, signaling their inclusion as part of the rabbinic canon and their relevance to contemporary spiritual challenges.

In his second introduction to Sefer Hasidim, Luzzatto emphasized the significance of the Aggada within the book. He stated that while its halachic content was important, the heart of Sefer Hasidim revolved around its aggadic passages, such as “rationales for the commandments (ta’amei ha-mitzvot), pleasant scriptural exegesis (peshatim ne’imim), homilies (d’rashot), ethical teachings (musarim), virtues (middot tovot va-y’sharot), and proper conduct (derekh eretz).” Luzzatto considered it meritorious to intelligently explicate and interpret the tales and occurrences recounted in the text. This viewpoint stood in contrast to de’ Rossi’s dismissal of the significance of Aggada. Luzzatto regarded all of this material as worthy of explication (drishah), just like any other aspect of Torah.

Luzzatto challenged de’ Rossi’s dismissal of Aggada while also praising the table of contents in his new edition. He stated that by examining the table of contents, one could quickly find “the source of the book itself.” Luzzatto emphasized the inclusion of references in the table to both laws and tales, and he reassured readers that using the table to locate notable passages was a reasonable way of uncovering the rich wisdom of Sefer Hasidim. There was “no harm or reason to fear,” Luzzatto wrote, “regardless of the method used to extract the pearl from the sand.”

The mention of extracting “the pearl from the sand” was an allusion to Maimonides’ “parable of the pearl” at the beginning of his Guide for the Perplexed. In the Guide, Maimonides proposed a theory of scriptural interpretation, suggesting that the true meaning of the words of Scripture was concealed and needed to be deciphered. The external meaning of parables, according to Maimonides, held no value compared to the internal meaning, likening the concealment of the subject to a man who dropped a pearl in a dark and cluttered house, unable to benefit from it until he lit a lamp.

For Luzzatto, Sefer Hasidim was like a pearl lost in a dark house, possessing profound yet hidden meaning. Its transmission, both orally and as a “secret scroll,” led to textual distortions, with passages containing stammering, distortion, repetition, and verbal corruptions. Luzzatto portrayed the process of extracting the true meaning from Sefer Hasidim as the retrieval of a precious pearl from sand.

However, there was a subtle discrepancy between Maimonides’ imagery of the pearl lost in a dark house and Luzzatto’s analogy of Sefer Hasidim being “extracted” from “sand.” This discrepancy arose because Luzzatto, in referencing the pearl, was actually quoting from de’ Rossi’s Me’or Einayim without attribution. In Me’or Einayim, de’ Rossi used the pearl as a metaphor for the questionable stories found in Aggada. According to de’ Rossi, these stories were like pearls mixed with sand, requiring careful sifting to separate the valuable from the unreliable.

De’ Rossi explained that the sages of antiquity wrote Aggada to assist their students in understanding the meaning of Scripture. They followed the method described by Maimonides in his Guide, where the teacher uses various means or even speculation to simplify complex premises for the student. Similarly, the sages of antiquity, according to de’ Rossi, created Aggada as an expedient to help students understand the message of Scripture and promote its understanding among the masses. Regardless of the method used to extract the pearl from the sand, “There was no harm or reason to fear if one explored and examined it to their heart’s content.”

Luzzatto, on the other hand, inverted de’ Rossi’s statement. While de’ Rossi saw the religious meaning of Scripture as the pearl obscured by fanciful aggadic elements (the “sand”), Luzzatto regarded Aggada, particularly the aggadic passages of Sefer Hasidim, as pearls hidden by textual distortions (the “sand”). Luzzatto believed that through proper editing and “correction” (hagahah), which he and his colleague Israel Zifroni had undertaken themselves, the religious treasure concealed within Sefer Hasidim could be uncovered.

However, if Sefer Hasidim was considered a work of Aggada, as Luzzatto claimed, how could R. Judah he-Hasid be its “author” (mehaber)? The second printed edition explicitly stated on the title page that Judah was the author of Sefer Hasidim. In his second introduction, Luzzatto clarified the meaning of this attribution …

Luzzatto wrote that Sefer Hasidim was composed of both the “statements of the tales and the occurrences ... the words themselves and their meaning,” as well as the “pure and refined words” added “by the mighty and pious author (mehaber) of blessed memory (referring to R. Judah he-Hasid).” The former referred to the preexisting aggadic material that had canonical status and originated in antiquity, similar to the Talmud or the Zohar. The latter referred to Judah’s own recent compositions. According to Luzzatto, authorship involved combining preexisting authoritative texts with the words of an author. Judah’s identity was not concealed or erased in this process, as it might have been in a medieval manuscript, but he was not depicted as a solitary genius creating Sefer Hasidim entirely from scratch, as one might imagine a modern author.

The excerpt is reprinted with minor modifications from Joseph A. Skloot, “First Impressions: Sefer Hasidim and Early Modern Hebrew Printing” (2023), with permission of Brandeis University Press.

Joseph A. Skloot is the Rabbi Aaron D. Panken Assistant Professor of Modern Jewish Intellectual History at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion/New York. He is a historian of Jewish culture and religious thought in the early modern and modern periods.