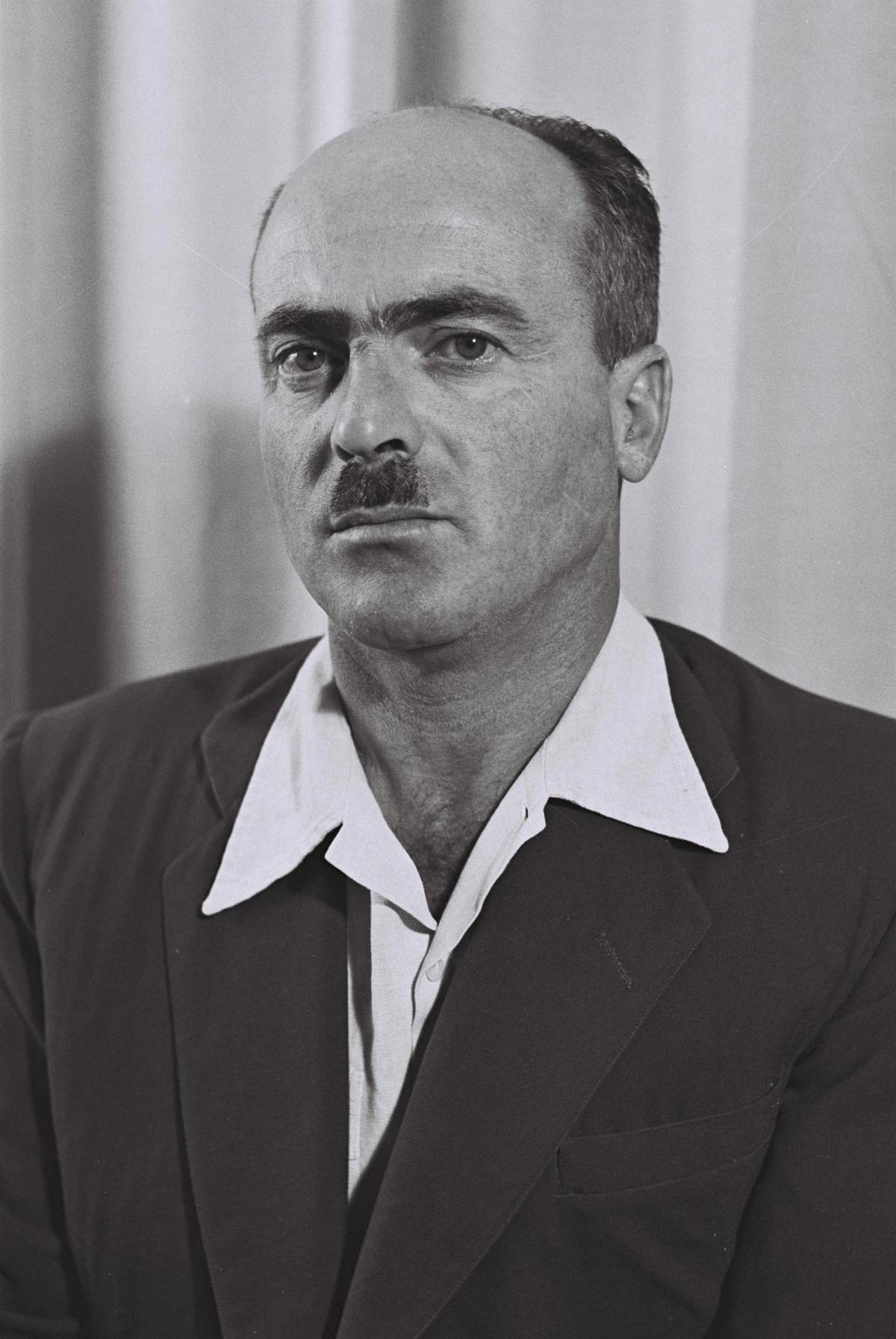

Teddy Kollek, the British Spy Who Never Was

Was the mayor of Jerusalem the liaison code-named Scorpion?

Teddy Kollek is revered as one of the founding fathers of Israel. Best known for having served as the mayor of Jerusalem for 28 years, he served alongside such iconic figures as Golda Meir, Moshe Sharett and founder and first Prime Minister of Israel David Ben-Gurion. So when in 2007 it was reported that Kollek had been a British agent code-named Scorpion who had given away information leading to the arrest of his fellow Jews, many Israelis were shocked. As Scorpion, Kollek was reported to have met with MI5 agents and to have disclosed sensitive information leading to the arrests of dozens of Irgun and Lehi fighters by the British.

Yet a fresh look at British files shows that the man who helped found the Mossad was never a British agent and wasn’t code-named Scorpion. Those same files also show that the left-wing ideologue Yitzhak Ben Aharon did in fact have powerful connections with British intelligence—a fact that has never before been revealed.

During World War II, Kollek was a key figure in Jewish Agency intelligence. Shortly after his death historians and journalists descended on newly declassified MI5 files relating to his activities in the 1940s. The files mainly record espionage targeting Kollek by the British state while he was based in London on behalf of the Jewish Agency. It was supposedly information in these files that led to the claim that Kollek was a spy called Scorpion.

But only one document in the archive contains the code name Scorpion. This is a letter written by Major James Robertson of MI5 outlining a plan for an MI5 officer, code-named Scorpion, to meet Kollek without revealing to Kollek that he worked for British intelligence. The letter was sent on Nov. 1, 1946, and documents the process through which Kollek would eventually be able to meet with MI5:

We have always been against any direct contact between the [Jewish] Agency and this office [MI5]. This was the reason for original suggestion that you might help us in the development of an indirect link through Kollek or one of his friends. Since my letter was written, however, the link developed itself fortuitously by reason of a personal acquaintanceship of some years duration between one Ben Aharon-whose name will be well known to you-and a member of this office. I propose in future to refer to this MI5 officer who is the source of the information contained in my letter cc.116,660/B3a/JCR of September 7th to Morris Oldfield and who is not in this section, by the codename Scorpion. His reliability is without question.

For professor Yoav Gelber of Haifa University, author of a three-volume history of Israeli intelligence, it’s now clear that Scorpion wasn’t Kollek: “the document proves clearly that Scorpion is British and a member of the MI5 team and now I can suspect on a substantial basis that he [Scorpion] was in captivity during World War II because he knew Ben Aharon and they were friends, so this is my conclusion—not 100% but let’s say 70%.”

There is no further mention in the declassified MI5 files of Scorpion but there are two reports of meetings between Kollek and individuals with ties to British intelligence in London. The first took place on Jan. 30, 1947, between an MI5 officer called Simkins, who would rise to become deputy director general of the service in 1965. The second is a report sent by a former colonel in intelligence, Martin Charteris, of having dinner with Kollek and Abba Eban. According to Simkins’ report, “we started by discussing Ben Aharon and his book ‘Listen Gentile’ which is due to be published shortly.” The name Ben Aharon comes up several times in the report, and the men use their shared friendship with him as a talking point.

As per Gelber’s prediction, Simkins was in fact a prisoner of war during World War II. Ben Aharon isn’t mentioned in the Charteris report. Charteris was never a prisoner of war.

But who is Ben Aharon and why does he feature so prominently in these intelligence reports? Why would Robertson write to a colleague of his “name that will be familiar to you”?

Gelber describes Ben Aharon as “a Bolshevik to his last day and he died in 2006, he was a doctrinaire, an ideologue, a personal example.” Ben Aharon, who would become a Member of Knesset and the head of Israel’s powerful labor union the Histadrut, is famous for a few things; one is signing a letter of condolence to the Russian people on the death of Stalin, another is advocating that Israel withdraw from the West Bank in 1968. He has never been associated with intelligence matters and Gerber dismisses the idea that he could be a spy. Nevertheless this man, who by all outward appearances had more sympathy with the Soviet Union than with the British Empire, was the man who brought British intelligence to the table with the Jewish Agency.

Gerber adds that Ben Aharon wasn’t completely removed from the world of intelligence, pointing out that his wife, Miriam, worked for the Haganah intelligence organization, Shai. “Miriam Ben-Aharon certainly rings a bell,” Gelber recalled. “She ran the Shai office in Jerusalem under Chaim Ben-Menachem from 1942 until, I think but am not sure, the summer of 1945, while Yitzhak was in German captivity. She was replaced by Carmela Yadin and in 1946/7 was in charge of dissidents’ matters (Irgun and Stern) in Jerusalem.”

To understand why it was so important to Kollek that Ben Aharon should come to London, it’s important to understand the relationship between the British and the Jewish Agency at the time. Just after Kollek arrived in London, the British Army descended on the Jewish Agency leadership in Palestine and detained many of them in the Latrun prison camp. A month later, the Irgun bombed the King David Hotel. This made Kollek’s job of forging links with the British much harder—but he was well known for finding ways of achieving his objectives, a reputation that would follow him throughout his years in Mossad and the Jerusalem mayor’s office.

Steven Wagner, historian of intelligence, security, empire, and the modern Middle East at Brunel University, emphasizes the decaying relationship between the British and the Jewish Agency in 1946. “Kollek until 1946 was the main liaison not just with the British but with the Americans also,” he said. “From 1944 till New Year’s ’45-’46, Kollek’s job is basically to drink with these British and American officers and give them the best information he has. But in early 1946 things are grim, and by the end of 1946 forget it, no one’s going to talk to you.”

It is at this “grim” moment in Anglo-Zionist relations, when the British mandate is falling apart and the Jewish Agency is pushing for Holocaust survivors to be allowed to come to Palestine, that Kollek reached out to the “Bolshevik” Ben Aharon to come to London to “renew and hand over” his contacts. Records show that by the 18th of September Ben Aharon was in London; less than two weeks later, Robertson wrote his letter mentioning Ben Aharon and Kollek and his plan involving Scorpion. The following January Simkins and Kollek met.

Wagner asserts that despite the bad relations between the British and the Jewish Agency, the information-sharing relationship Kollek was attempting to maintain was helpful to both sides. “I’ve argued in my paper, Whispers from Below, that actually the British access to Jewish Agency’s information on terrorists abroad is very helpful even at this low point in their relations. The Jewish Agency doesn’t want these kinds of big incidents in Europe or London to go off and harm the progress they’re making on public opinion about Aliyah Bet [illegal Jewish immigration to Palestine].” Wagner adds that “there’s nothing treasonous in this, in fact, this was kind of core to where Zionist power was coming from. They were fostering this dependency on their information.”

It may never be known definitively how Ben Aharon built relationships with British intelligence officers or if Simkins was definitely Scorpion. But what is clear from the files is that Ben Aharon’s contacts with British intelligence did exist. It is also definitive that Kollek was not the British agent code-named Scorpion.

In the files there are copious reports detailing surveillance on Kollek. His phone was bugged, his bags were searched, he was questioned when he entered and left Britain, his movements around Europe were tracked and substantial effort went into trying to ascertain what he was doing both in London and in Europe. These are not the activities of an intelligence service running an agent but of spies attempting to outwit an adversary.

Marc Goldberg is the author of Beyond the Green Line: A British volunteer in the IDF during the al Aqsa Intifada.