The Return of the Swastika

In 1959 there was a global swastika epidemic. What does the last resurgence of this symbol of Jewish hatred tell us about the current one?

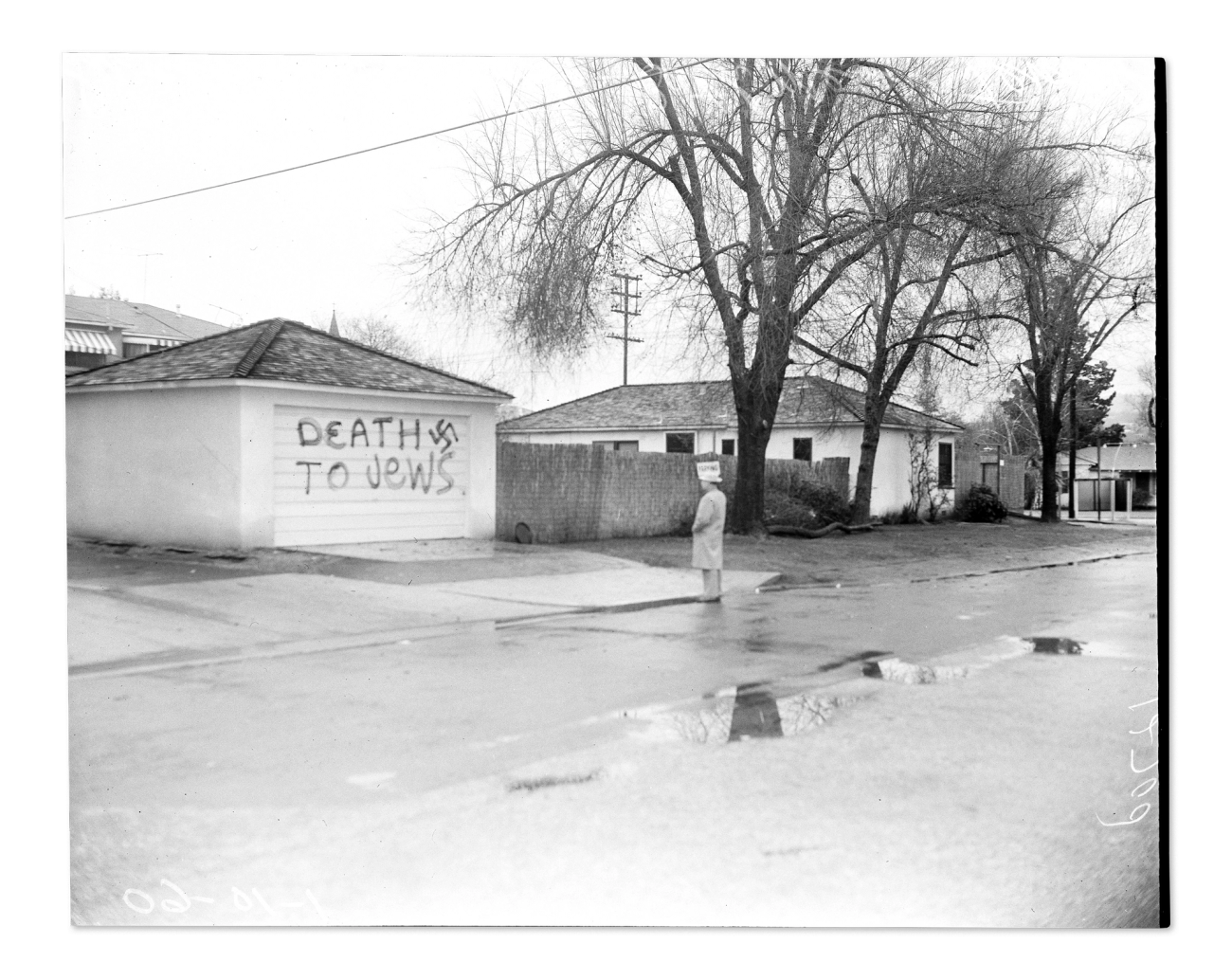

Los Angeles Examiner/USC Libraries/Corbis via Getty Images

Los Angeles Examiner/USC Libraries/Corbis via Getty Images

Los Angeles Examiner/USC Libraries/Corbis via Getty Images

On Christmas Day, 1959, a newly rededicated synagogue in Cologne, Germany, was prominently defaced with swastikas. Immediately thereafter, a “swastika epidemic” broke out in over 20 towns and cities across West Germany, targeting other synagogues, Jewish cemeteries, and Jewish-owned shops. “Death to Jews” and “Jews go home” were among the antisemitic slogans that accompanied this sudden outpouring of Nazi sentiment. In no time at all, a wave of similar incidents occurred around the world. By early March 1960, swastikas appeared seemingly everywhere, so much so that within a three-month period, public expressions of anti-Jewish hatred occurred in 34 countries. In the United States alone, 637 incidents of this kind were recorded in 236 cities and small towns, some of them accompanied by death threats and attacks on Jews and Jewish institutions.

Many were shocked, for under the sign of the swastika Jews had been murdered by the millions in some of the same countries now witnessing this sudden outpouring of hostility against Jews. Was this renewed display of Jew-hatred a continuation of Hitlerian passions or would it pass?

Answers were not easy to come by, but the “swastika epidemic” of 1959-60 petered out after a time, and the antisemitism it represented became relatively quiescent for a while.

It has revived in our own day, and energetically so. Swastikas are back, and the hatred they symbolize is more vocal, more visual, and more pervasive than it has been for decades. Especially since Hamas’ massacre of Israelis on Oct. 7, Jew-hatred, often in the form of Israel-hatred, is vociferously and unapologetically on display on college campuses, in large street demonstrations, on social media, and in segments of America’s political, and cultural life. The “exhilaration” that a Cornell University professor expressed in the immediate aftermath of Hamas’ butchery of Jews is symptomatic of a larger euphoria brought on by that pogrom. Almost overnight, the Jewish victims were denounced as villains.

One sign of the emotional high triggered by this hatred is the reappearance of swastikas. In addition to swastika graffiti and a range of anti-Jewish hate messages appearing in public places in New York city and elsewhere, the Nazi symbol frequently shows up in anti-Israel street protests, sometimes in novel ways. Examples include people in crowds holding up cellphones whose screens show large swastikas. More elaborate are handmade posters featuring a large swastika pointing to the words “Israeli Military = Nazis.” Or signs with blood-stained swastikas intertwined with the Star of David. Or large swastikas supplanting the Star of David in the middle of refashioned Israeli flags. In still another perversion of this same visual ploy, American flags have been redone to show the stars replaced by swastikas and “Free Palestine” inscribed between the stripes.

Swastikas are back, and the hatred they symbolize is more vocal, more visual, and more pervasive than it has been for decades.

These graphic anti-Jewish accusations lend visual force to the further demonization of Israel, a process that has been going on for many years now and has become reenergized since Hamas’ assault on Oct. 7. The atrocities that took place on that day should have provoked a sharp sense of horror and outrage. In some, it did. In others, something weirdly akin to elation occurred, and it continues to this day with robust shouts of “Israelis are Nazis,” “Hitler was right,” and “gas the Jews.” Add the formulaic denunciations of Israel as a “racist,” “apartheid,” “settler colonial,” and “genocidal” state unworthy of a future, and we confront questions similar to those provoked by the “swastika epidemic” of 1959-60.

What brought on this wave of open hatred? How long is it likely to last? How much damage will it cause? And what can be done to restrain it and forestall a repeat?

It is too soon to answer all these questions, but the first one may be clarified by what we know about who triggered the events of 1959-60. After the worst of that seemingly spontaneous torrent of raw Jew-hatred subsided, it was discovered that some of the neo-Nazis responsible for the spread of the swastikas and anti-Jewish slogans had been recruited by the KGB, which had launched an ambitious disinformation campaign against West Germany carried out by Soviet secret agents in East Germany. The Russian aim was to expose the newly denazified German state as still incorrigibly infected by Nazi ideology and thereby weaken its alliance with Western nations. For a short time, the operation succeeded, as questions were raised about the true character of West Germany: Was the successor to Hitler’s Germany in fact a liberal democratic state worth supporting or not?

In some quarters, today’s version of the earlier “swastika epidemic” is raising similar questions, but this time about Israel. Is the Jewish state an ally worthy of ongoing diplomatic and military support as it seeks to defend itself, or is it time to weaken those ties? Judging by the celebratory fervor on display in post-Oct. 7 street rallies and campus protests, there are clearly numbers of people who would like to see a weaker, more vulnerable Israel. Some would like to see no Israel at all.

For whom is such an outcome desirable? Russia, to draw attention away from Putin’s war against Ukraine? Qatar, a longtime supporter of Islamist groups, including Hamas, whose political leadership it houses in Doha? Iran, to further heighten annihilationist threats against Israel? Raising and answering these questions is imperative.

Foreign influences aside, the homegrown version of this impassioned animosity is easier to decipher. Some of it has been long gestating on college campuses and has been mainstreamed in the name of such progressive values as peace, social justice, and human rights. All three are commendable and are worth pursuing, but not as they are underwritten by the dogmatic imperatives of critical race theory, intersectionality, and post-colonialism and advocated by people shouting antisemitic slogans.

Unless one’s mind has been altogether corrupted by a steady diet of ideological obscenities, certain words and symbols should never be used when referring to Jews. One of these, for reasons that should require no explanation, is “gas,” but within 48 hours of Hamas’ massacre of some 1,200 Israelis on Oct. 7, a crowd outside the opera house in Sydney was already shouting “gas the Jews.” Shamefully—and yet the people who hurl these murderous taunts feel no shame—the same obscenity and others like it are sometimes sounded by people waving Palestinian flags on campuses and in anti-Israel street demonstrations. Kaffiyeh-clad, some are young people from Middle Eastern countries studying at American colleges and universities. Others, sometimes also sporting kaffiyehs, choose to be allies with those chanting “from the river to the sea” and “intifada revolution.” They see themselves as combatants in today’s culture wars, pitting the “oppressed” against the “oppressors,” with Israel and Jews condemned as being on the “wrong side” of this simplistic but popular equation. The slide from there to an embrace of full-throated anti-Zionism and antisemitism is often quick and easy.

It will take a while to sort through all these developments, but a few things are already clear. Haters need to hate, and antisemitism, always in recruitment mode, is readily available, open to all, and a common, easily accessible hatred. Those who embrace it on social media, college campuses, on the street, in the entertainment and sports worlds, and elsewhere, quickly find like-minded allies and probably believe that those they hate and are dedicated to hurting won’t hurt them back. That may have been true when Jews were set upon in the past. It is not true of Israeli Jews. When they are hit, they hit back, and hard. For that, they and Jews everywhere are hated even more.

The most potent sign of that visceral hatred is the return of the swastika. Expect to see more of them, this time not just as an antisemitic symbol but also an anti-Israel one. Just as the “swastika epidemic” of 1959-60 revived a latent Jew-hatred among people in Germany and elsewhere, something dangerously similar is occurring in the aftermath of Hamas’ savage attacks of Oct. 7. As I write, bomb threats have been made against hundreds of synagogues in 17 American states. The threats are no doubt a ruse, but they are typical of the aggressively mean-spirited passions let loose across the United States and around the world. If we do not quickly and effectively find ways to restrain this growing hatred, the future prospect for Jews and others may become more frightful than it has been since the 1930s.

Alvin H. Rosenfeld is the director of the Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism and Irving M. Glazer Chair in Jewish Studies at Indiana University, Bloomington. He is the editor, most recently, of Resurgent Antisemitism: Global Perspectives.