The Stronghold

On the prayer recited for IDF soldiers

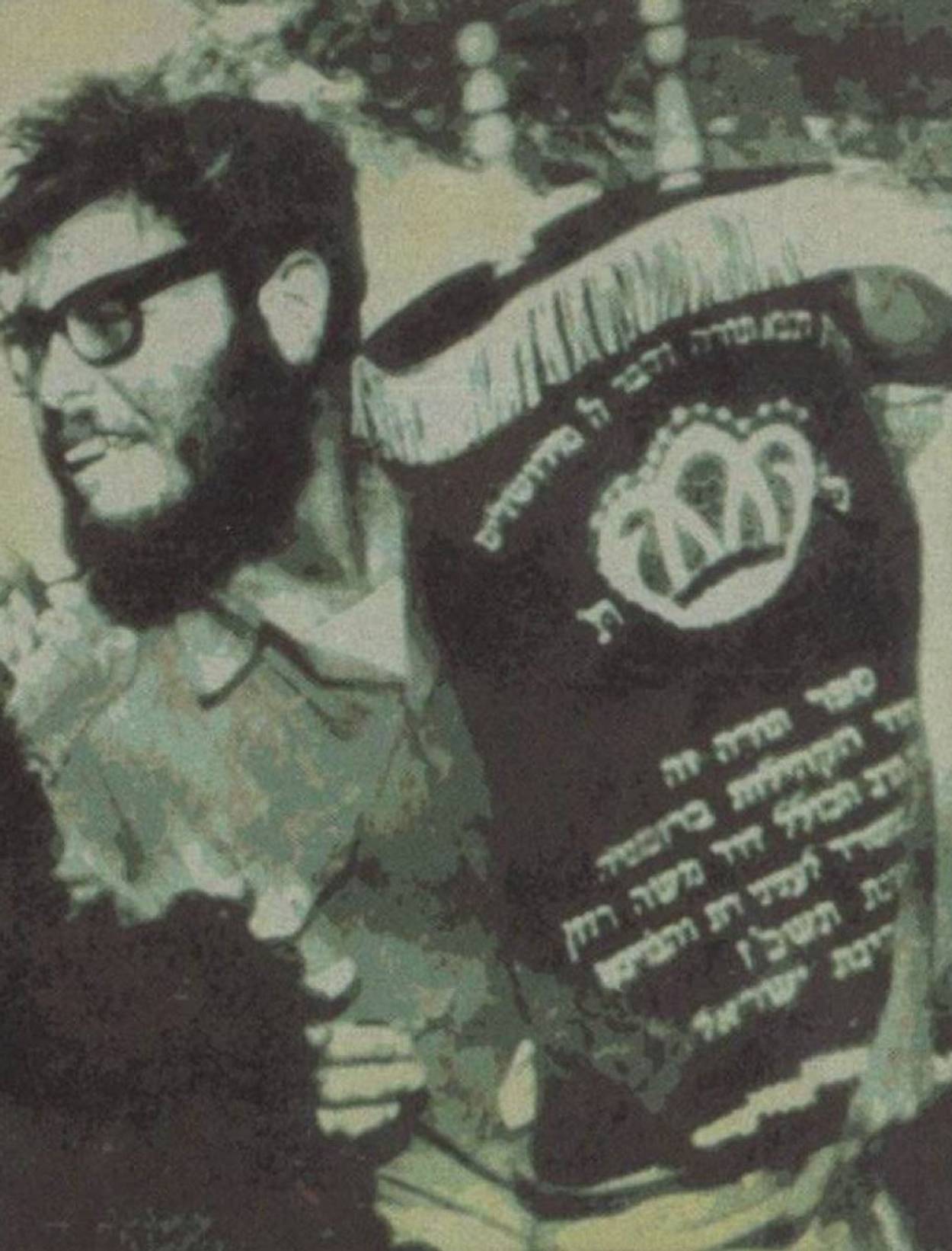

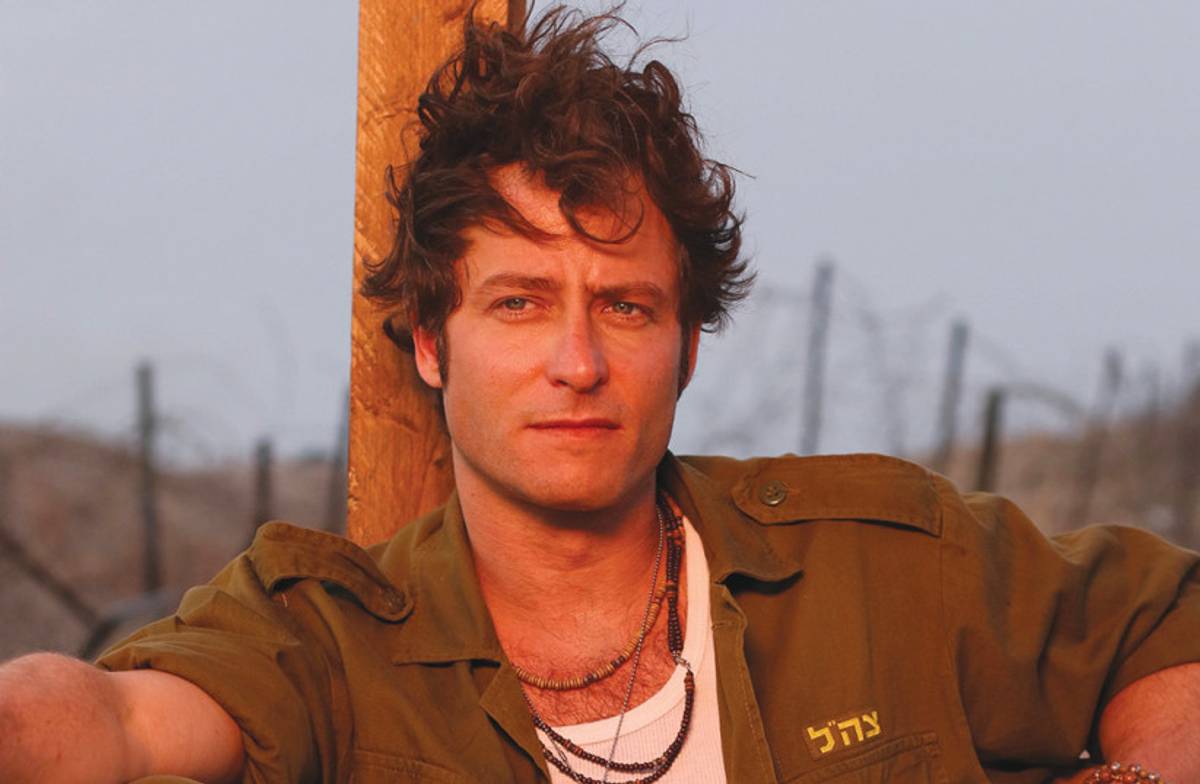

Photo taken from the cover of ‘Hillel from the Mezach Strong,’ by Menachem Michelson, 1997

Photo taken from the cover of ‘Hillel from the Mezach Strong,’ by Menachem Michelson, 1997

Photo taken from the cover of ‘Hillel from the Mezach Strong,’ by Menachem Michelson, 1997

Photo taken from the cover of ‘Hillel from the Mezach Strong,’ by Menachem Michelson, 1997

In 1973, during the Yom Kippur War, the world was introduced to Hillel Unsdorfer, a remarkable soldier whose story transcends the clichés of heroism. Born in 1952, he was named after his paternal grandfather, Rabbi Hillel Unsdorfer. His grandfather had been educated at the Pressburg Yeshiva under the guidance of Rabbi Akiva Sofer and Rabbi Yosef Tzvi Duschinsky. From 1920, he served as the rabbi of Lucenec in Slovakia, renowned for his deep understanding of Jewish law and active community engagement. Tragically, he perished in the Gunskirchen concentration camp in 1945.

A young religious Israeli soldier, Unsdorfer served in a Nahal brigade and was stationed in a bunker along the Suez Canal. Armed only with rifles, he and his IDF unit confronted advancing Egyptian tanks. Their unit, consisting of just 42 men, held off hundreds of Egyptians for a full week. By the third day of battle, they realized that all other Israeli fortifications had fallen, leaving them as the sole remaining force in combat against the Egyptians. Reflecting a decade later, Unsdorfer remarked, “There’s no way I can explain in military terms how we stood up to the attack.” One remarkable example of their heroism during that week was when a fellow soldier sacrificed his life by jumping on top of a grenade that had been thrown into their fortification. Unsdorfer remembered, “If he hadn’t done that, everyone would have been killed.” Despite their miniscule odds of victory, the 42 soldiers refused to surrender, even when their division commander informed them via radio that the rest of the Israeli army couldn’t reach them. They persisted for a few more days until Moshe Dayan, then the defense minister, ordered them to surrender, cautioning that not doing so would be suicidal. But later, shortly before they surrendered, Moshe Dayan changed his order, as he didn’t want posterity to remember him as the man who gave the “surrender” order.

Throughout their roughly monthlong captivity in the custody of the Egyptian army, the Israeli prisoners of war had contact with a Red Cross representative. However, once that Red Cross representative left, they faced physical assault at the hands of the Egyptians. Unsdorfer had his personal belongings, including his watch, glasses, and kippah, confiscated, and his tzizit were forcibly ripped from beneath his shirt. Foreign journalists, reporting on the war from Egypt, captured a powerful image of Hillel Unsdorfer and his unit on their way to their captivity. In the photograph, Unsdorfer is seen embracing a Torah scroll in his arms. This iconic image rapidly gained worldwide recognition and emerged as a lasting symbol of strength for the Jewish community in the wake of the traumatic Yom Kippur War. Rabbi Hillel Unsdorfer later served as the rabbi at Kibbutz Beit Rimon in the Lower Galilee, where he was deeply committed to strengthening Jewish agricultural communities guided by Jewish law.

A decade after the Yom Kippur War, Rabbi Hillel Unsdorfer explained to a reporter why he chose to carry the Torah scroll across the Suez Canal and into captivity, saying, “Most of us felt we should take the Torah with us to Egypt because it watched over us while we were fighting. We felt it should stay with us and continue to guard us.” Reflecting further, he added, “I have no idea how the Egyptians knew I was wearing tzizit. They took all religious symbols off us for the same reason they started the war on Yom Kippur—the war was really against Judaism and Jews, not only against Zionism and Israel.” Eventually, an agreement between the Israeli and Egyptian governments led to the exchange of provisions for the Israeli prisoners of war, resulting in their release.

Tragically, in 1993, two decades after his release from captivity, Rabbi Hillel Unsdorfer’s life was cut short in a car accident in the Galilee at the age of 41. He left behind his wife and five children. In the week before his untimely death, Rabbi Hillel Unsdorfer submitted a thought-provoking article to the ha-Tsofeh religious Zionist newspaper. His analysis of the Mi Sheberach prayer for IDF soldiers centered on the phrase “from the border of Lebanon,” arguing that it held broader implications than mere geography, extending beyond the political border. He emphasized the prayer’s apt reflection of the daily realities faced by IDF soldiers, asserting its continued relevance without the need for changes due to shifting geographical circumstances. This insightful article, a response to Rabbi Alexander Malkiel’s earlier article published the previous month in the ha-Tsofeh Literary Supplement, was enriched by Rabbi Unsdorfer’s own harrowing experiences during his captivity in Egypt, which provided him with a unique perspective on the nuances of the Mi Sheberach prayer. In the introduction to Rabbi Unsdorfer’s final article in ha-Tsofeh, the editor poignantly reminded readers of Unsdorfer’s legendary act of carrying the Torah into Egyptian captivity.

Most of us felt we should take the Torah with us to Egypt because it watched over us while we were fighting. We felt it should stay with us and continue to guard us.

Rabbi Avraham Shapira, then-Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Israel and rosh yeshiva of Yeshivat Merkaz HaRav, had, several years prior, provided a historical and spiritual interpretation of the same phrase in the Mi Sheberach prayer, presenting a striking contrast to Rabbi Unsdorfer’s view on the subject. Discovered later in the archives of the Israeli Chief Rabbinate, Rabbi Avraham Shapira’s insights on the Mi Sheberach prayer were articulated in an unpublished responsum dated Feb. 28, 1988. There is no indication that Rabbi Unsdorfer was aware of or had access to this document when he wrote his article in ha-Tsofeh. Shapira wrote:

Danny Schwartzman/United King Films

There is no place to ‘amend’ prayers that were established by eminent rabbis in the past. The phrase ‘from the border of Lebanon’ does not refer to the political border between Israel and the state of Lebanon. Geographically, the Upper Galilee and the mountains of southern Lebanon constitute one geographical region. From the history of Jewish settlement in the northern part of the Land, Jewish communities that were located in the Upper Galilee, which today are, from a political perspective, within the territory of Lebanon. Therefore, the words ‘from the border of Lebanon’ have a broader significance beyond geography and do not only refer to the political border.

As the 50th anniversary of the Yom Kippur War approached in early October 2023, renewed interest on social media highlighted the story of Hillel Unsdorfer and his unit’s Torah scroll, symbolizing not only historical remembrance but also contemporary resilience. In 2023, coinciding with this milestone, The Stronghold, a television series dramatizing the experiences of Unsdorfer’s unit, was released to commemorate the anniversary.

The Torah scroll, referred to as “The Prisoner,” which saw its return to Israel in 2000 through the efforts of then-President Ezer Weizmann and Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, now resides in the IDF Military Rabbinate Corps at Shura Camp. The saga of this Torah scroll, marked by its captivity and eventual return to Israel, symbolizes renewal amid despair and serves as a beacon of hope during Israel’s current conflict with Hamas. Rabbi Unsdorfer’s insightful writings on the Mi Sheberach prayer remind us “that the prayer encompasses all the IDF soldiers wherever they may be.” We hope and pray for the safe return of all the hostages from Gaza, and may they be speedily reunited with their families and with all of Israel.

Hillel Unsdorfer

“On the Text of ‘Mi Sheberach’ for IDF Soldiers”

ha-Tsofeh Literary Supplement

(12 February 1993): 7 (Hebrew)

[Hillel Unsdorfer, the rabbi of Kibbutz Beit Rimon who died in a road accident at the age of 41, was known during the Yom Kippur War when he fell into Egyptian captivity with other fighters from The Pier Outpost and left the outpost with the Torah scroll in his hands. A few days ago, Rabbi Hillel Unsdorfer sent us the article about the prayer Mi Sheberach for the IDF soldiers, and these words will be a candle in his memory. —ha-Tsofeh Editor]

On Friday, the 15th of Tevet, an article by Rabbi Alexander Malkiel was published regarding the Mi Sheberach prayer for the Israel Defense Forces soldiers. In his article, the author quotes the Mi Sheberach prayer, but in the prayer’s quotation, we find a difference from what is written in the prayer books.

I would like to address the change proposed by the author. It is stated there: “‘... the soldiers of the Israel Defense Forces who stand guard over our land and the cities of our God, from Lebanon to the desert of Egypt.’ And in a note there he writes, ‘In prayer books, it is written as ‘from the border of Lebanon.’ But since this wording does not reflect the current reality, as our soldiers also operate beyond the border within Lebanon, it is appropriate to say ‘from Lebanon’ so that these soldiers are also included in this prayer. That’s all.”

This change, not to say “on the border of Lebanon,” began, to the best of my memory, during the Lebanon War (in 1982). At that time, many prayerful individuals who considered and emphasized their prayers felt the desire to pray and bless the soldiers who were fighting and dedicating themselves to our defense. Therefore, they omitted the word “on the border,” and thus they included in their prayers the soldiers operating within Lebanon beyond the border, as indicated in the note.

Regarding such matters, our sages have said, “Anyone who adds, in fact, subtracts.” While we have indeed added the soldiers located within Lebanon to our prayers, what about the soldiers sent each day from beyond the great sea or beyond the desert, to stand guard over our land? What about the soldiers who were sent in their time to Operation Entebbe, whose self-sacrifice added security to those of us residing in the cities of our God? Thus, one can count hundreds and thousands of actions to which our soldiers are dispatched beyond the borders and are not located in Lebanon.

And the question arises regarding these soldiers who are in a high- risk position: Do we not pray for them that the Almighty will watch over them, save them, send blessings and success upon them, crown them with the crown of salvation and the wreath of victory? Do we truly only pray for those soldiers within these borders?

If so, the inquirer may ask, should we change the entire Mi Sheberach prayer to include all the soldiers, including those outside our borders? Perhaps it would be wise to omit specifying the borders altogether?

In my humble opinion, there is no need to change the prayer at all. Instead, we should return to the prayer written in the prayer books and cancel the change made by “the meticulous ones.” Then we will realize that the prayer encompasses all the IDF soldiers wherever they may be. We only need to understand what we are saying.

In the Mi Sheberach prayer, we pray for the IDF soldiers who “stand guard over our land and the cities of our God,” and what is our land? What are its borders?—“From the border of Lebanon to the desert of Egypt and from the Great Sea to the Aravah.”

Our soldiers, who stand guard over our land, are located “on land, in the air, and at sea.” This means that the passage beginning with the words “from the border of Lebanon” and ending with “to the Aravah” is essentially enclosed in quotation marks, and its intention is to encompass “our land and the cities of our God.”

Even our soldiers who cross these borders in their service to the IDF do so to defend our land within the mentioned borders. Therefore, the prayer written in the prayer books accurately reflects the daily reality.

And every military action, as it is, does not require changing the order of the prayer.

Here, I would like to express my gratitude to Rabbi Alexander Malkiel, who, time and time again, enlightens our eyes with the precision of prayer and awakens our hearts to genuine intent in prayer. May the Almighty to confirm His redemption to our prayer and with a crown of victory.

This article is reprinted from “Praying for the Defenders of Our Destiny: The Mi Sheberach for IDF Soldiers,” ed. Aviad Hacohen and Menachem Butler (2023), with permission of the author.

Menachem Butler, an associate editor at Tablet Magazine, is the program fellow for Jewish Law Projects at the Julis-Rabinowitz Program on Jewish and Israeli Law at the Harvard Law School, and a co-editor at the Seforim blog. Follow him on Twitter @MyShtender.