Yiddish Folk Song in Classical Music

Since before the 18th century, Jewish folk melodies have had a rich, unexpected influence on musical composition

On Nov. 30, 1900, an overflow crowd of enthusiastic listeners—Jews and non-Jews alike—filled an auditorium in Moscow to hear a lecture on Yiddish folk music, followed by a concert. The lecture was given by the lawyer, amateur historian, and folklorist Peysekh Marek. The new concert arrangements of Yiddish folk songs and Hasidic nigunim that followed were created and introduced by the composer, music critic, and musicologist Joel Engel. Over the coming years, Engel would release numerous published volumes of folk-song arrangements, which in turn inspired a St. Petersburg-based group of composers including Lazare Saminsky, Aleksandr Krein, Mikhail Gnesin, Joseph Achron, and Solomon Rosowsky to follow a similar path under the auspices of their newly founded Society for Jewish Folk Music.

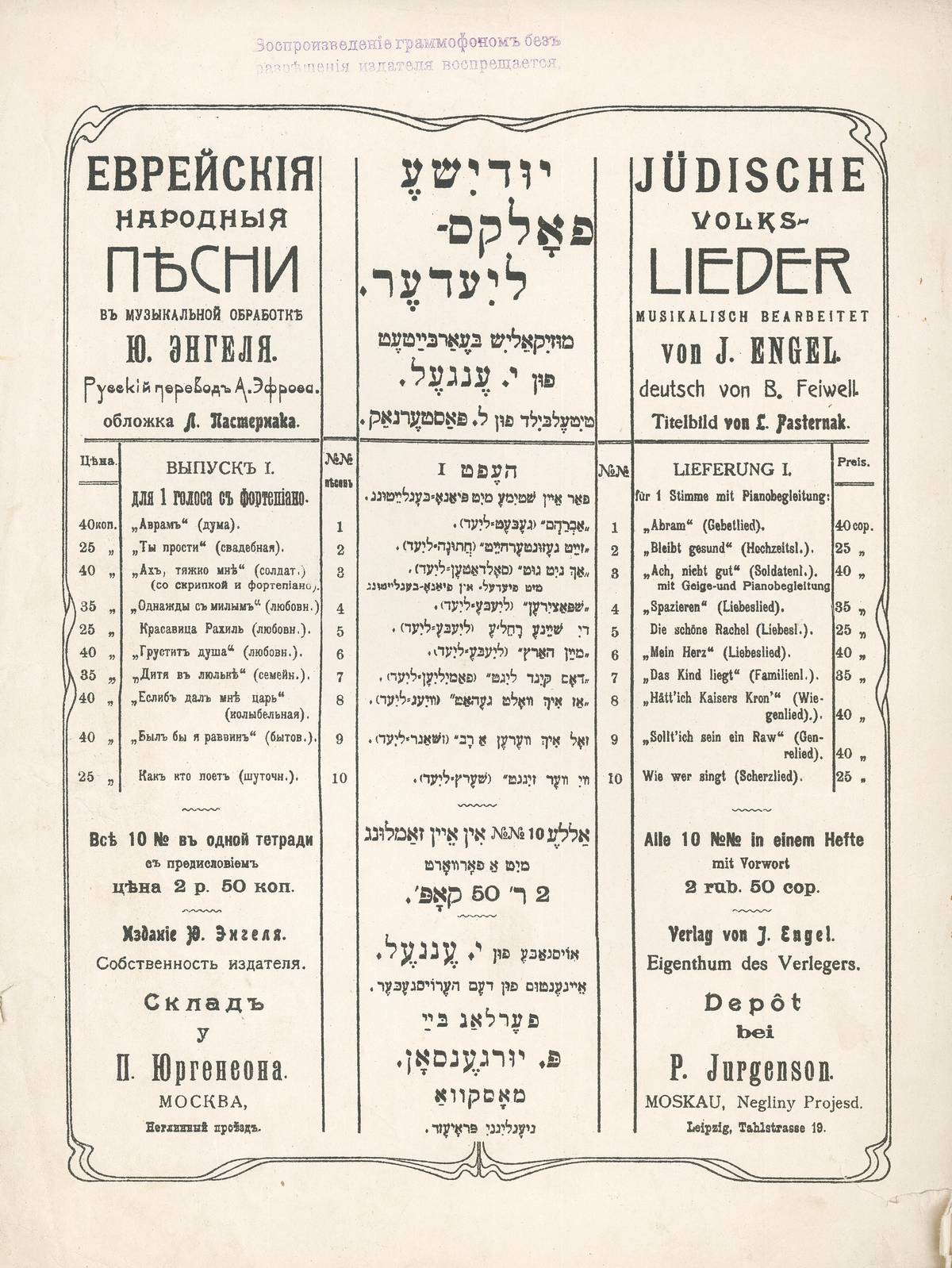

Marek’s lecture on that day in 1900 was actually the introduction to a book he authored together with historian and folklorist Shaul Ginsburg, Evreiskiia narodnyia piesni v Rossii (Jewish Folksongs in Russia)—the first large-scale attempt to document, preserve, and study Yiddish folk songs. Created through crowd-sourced song collection, the book contained only the song texts, but not the melodies of its 376 folk songs. Engel then created a supplement to this volume in which he provided melodies of 10 of the folk songs presented in his own newly composed arrangements with piano.

While Engel’s goal for these publications and for his arrangements for the November 1900 concert was to create an ethnographic resource, he also subtly but profoundly transformed the folk songs he chose by making versions that could be performed on the concert stage. In turn, this process of adaptation allowed Engel and the composers who followed him to contemplate the meaning and relevance of Yiddish folk song removed from the traditional world that first gave them voice, while utilizing their musical training and sometimes avant-garde sensibilities.

The idea of incorporating folk songs into classical music was hardly unique to Jewish ethnographers and artists: Composers in Russia like Mikhail Glinka and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov had been incorporating Russian folk songs into their work before Engel was born. In fact, classical composers have incorporated folk music into their compositions long before the concept of folk music was articulated as such, back in the 18th century.

The case of Yiddish folk song was unique for two reasons, however. First, rather than exploring the roots of songs with an accepted local cultural currency, Yiddish folk song was for many Jewish composers a way of reconnecting with cultural roots. Engel’s own assimilated, Russian-speaking family background was characteristic of many of the composers associated with the Society for Jewish Folk Music, as well as many Jewish composers of the later 20th century and early 21st century who turned to Yiddish folk song not knowing any Yiddish at all.

The second has to do with the status of Yiddish and Jewish peoplehood. Antisemites like composer Richard Wagner derided Jews as a rootless people without a legitimate folk culture of their own. “The Jew speaks the language of the nation in whose midst he dwells from generation to generation, but he speaks it always as an alien,” foamed Wagner in his famous essay Jewry in Music (1850). For Wagner the folk spirit was an essential inspiration for the creation of great art, but, “Where is the cultured Jew to find this folk?” Wagner rhetorically asked. “The only musical expression offered to the Jewish tone-setter by his native folk is the ceremonial music of their Jehova rites,” though this too, Wagner goes on to explain, comes down to the Jews “senseless and distorted.”

Even among Jewish intelligentsia, Yiddish folk song was not always taken seriously. Historian Simon Dubnow championed the study of Jewish folk culture, urging Jews to collect the materials of Jewish history and life. Yet when it came to Jewish folk music in particular, Dubnow’s position was not all that different from Wagner’s. “The Jew never sang outside the synagogue,” Dubnow wrote in his famous 1891 essay in the St. Petersburg Jewish journal Voskhod (Dawn), “his songs, anguished or joyous, were always prayers.” Engel’s work provided a resounding rebuttal to those that posited that a secular Yiddish folk song—analogous to the folk-song cultures of other nations—did not exist, and therefore to those who would assert that Jews were not an actual people.

The Society for Jewish Folk Music soon expanded its work to affiliated branches in Moscow, Riga, Odessa, and elsewhere. In the years following the Russian Revolution, when many of the composers involved immigrated to the United States and Jewish Palestine, it was reorganized under different institutional structures, none of which could replicate the society’s initial burst of creativity. While new publications of Yiddish folk songs with their melodies—and in later years archives of field recordings—have allowed composers to turn to Yiddish folk song in their work, their history is best conceived of through the ways they interact with their source material and the reasons they engage with Yiddish folk song, rather than as a continuous development of a single style or intellectual project.

With that in mind, I have created a taxonomy to describe the ways that composers since Engel have absorbed Yiddish folk song into their compositions. The first category I call the “jewel in a box.” In these compositions a folk song is faithfully presented but framed with a newly composed accompaniment and perhaps garnished with an introduction, interlude, and/or postlude. Such settings often come with an ethnographic impulse. This was certainly the case with Engel’s original arrangements and many other compositions by composers affiliated with the Society for Jewish Folk Music.

The ethnographic impulse of the “jewel in a box” approach fades in works with particularly inventive accompaniments in which an ornate “box” vies for the attention of the folk “jewel.” An early example is Maurice Ravel’s L’énigme éternelle (1914), an arrangement of the song Di alte kashe (The Old Question). L’énigme éternelle features such imaginative harmonies that rather than simply showcase the melody, Ravel colors it as special, distant, even perhaps “exotic,” if lovingly so. French Basque and not Jewish, Ravel wrote this arrangement around the same time he wrote a slew of other folk-song settings including Spanish, French, Italian, and Greek folk songs, and a setting of the Aramaic Kaddish text.

Stefan Wolpe’s Arrangements of Yiddish Folk Song (1923-25), are similarly distant from the ethnographic impulse with their striking and unconventional piano accompaniments. While the melodies and text are presented faithfully as transcribed in Wolpe’s source for the songs (Fritz Mordechai Kaufmann’s Die schönsten lieder der ostjuden, 1920), Wolpe’s modernist settings pit their source material against hazy chromatic harmonies and strident, angular dissonances.

Is Wolpe marking the exotic nature of these songs from his cosmopolitan perch in Berlin? Is he lamenting a world that is slipping away to modernity? While his musical project claims an implicit solidarity with the Yiddish-speaking Jewish masses, Wolpe was a German-speaking Jew and his composition seems to meditate on his own distance from the world of the originals.

In another approach altogether—let’s call it the “wellspring” approach—pieces depart further from their folk-song material after using it as a launching point for musical variation. A good example from the Society for Jewish Folk Music publications is Joseph Achron’s Hebreishe viglid (Hebrew Lullaby) (1914) for violin and piano. This short composition begins with a relatively straightforward presentation of a Yiddish lullaby, and then spins out material with the melody featured in free variation and elaborations, closing with a virtuosic flourish. A fitting contribution for a composer who was also a virtuoso violinist, the work is a charming showpiece that could be a poster child for the idea of classical music written in a Jewish musical language.

Some pieces take the reverse tack: Rather than taking a folk song as a launching point, they arrive at a folk song, as if discovering it. Let’s call this the “discovery” approach. Here the folk song is a kind of musical oasis in a landscape composed of related but, on its surface, different material.

The Old Question (2020), a piece I wrote for violin and piano, is an example. The work begins with a section of music that is searching and expressive, only to reveal close to its end that the thematic material has all been fragments and refractions of bits of the famous Yiddish folk melody, Di alte kashe, which is then presented in my own reharmonization as the close of the work. Here the process of engaging with the folk song is dramatized, and the journey toward the folk song as the fount of the musical material of the composition plays out as the work unfolds. In this kind of work the structure—rather than the harmony—articulates a kind of distance from the source.

If you take the music of either the “wellspring” or the “discovery” models, but remove a presentation of the folk song itself, you get a piece crafted with the musical DNA of the original, but only a loose, more general connection to it. I call these pieces examples of “free fragmentation.” Recent works Unter soreles vigele (2020) by Judith Shatin, and Farewell (2019) by Aaron Kernis fall into this category. They both use fragments of their original folk tunes to capture the sentiment and sound world, but freely compose using these melodic motifs to create their own new musical settings.

Finally, some works incorporate whole Yiddish folk songs into larger musical structures—let’s call this the “inlay.” The most famous of this last approach is (non-Jewish composer) Sergei Prokofiev’s Overture on Hebrew Themes (1919). As is common for overtures, the piece employs the structure of sonata from the presentation of two contrasting themes, a development section, and then a return of the two themes. Prokofiev takes as his two themes two folk songs: the first a Freylekhs dance tune, and the second the wedding-lament tune Zayt gezunterheyt—the same tune Aaron Kernis used for his Farewell, which is also found as the second song of Engel’s original 1909 set.

More recently composer Julia Wolfe featured the song Mit a nodl, on a nodl (With a needle, without a needle) in the second movement of her work for chorus and orchestra Fire in my mouth, which depicts the activity of the doomed Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. The melody is sung by a women’s chorus, nearly half-way into the movement, over churning strings, pulsating winds, and rattling percussion which depict the busy work taking place in an almost cinematic musical rendering of the historic scene. After the melody has been introduced, an Italian folk melody is added on top of it in counterpoint, depicting some of the cacophony of the scene while musically representing the other ethnic group present.

As a composer, I see engaging with Yiddish folk song as a way to build a new Jewish culture that has its roots set in the Jewish culture of the past. If Jewish continuity is a golden chain, this material is gold with which we can create the latest link.

Adapted in part from “Composing With Yiddish Folksong: A Composer’s Perspective,” featured in the festival program book for YIVO’s May 2022, Continuing Evolution: Yiddish Folksong Today

Alex Weiser is a composer and the Director of Public Programs of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. His debut album, and all the days were purple, was named a 2020 Pulitzer Prize Finalist for Music.