The Forest for the Trees

Tu B’Shevat might not seem like the most important event on the calendar this year. But it’s a reminder that seeds we plant today will bear fruit tomorrow.

Original photo: Wikipedia

Original photo: Wikipedia

Original photo: Wikipedia

Original photo: Wikipedia

Rainouts are the worst. Having suffered through my fair share sitting in the nosebleed seats at Yankee Stadium as a game is called off, I can only imagine what hundreds of schoolchildren in Jerusalem must have felt like on the morning of Tu B’Shevat back in 1914.

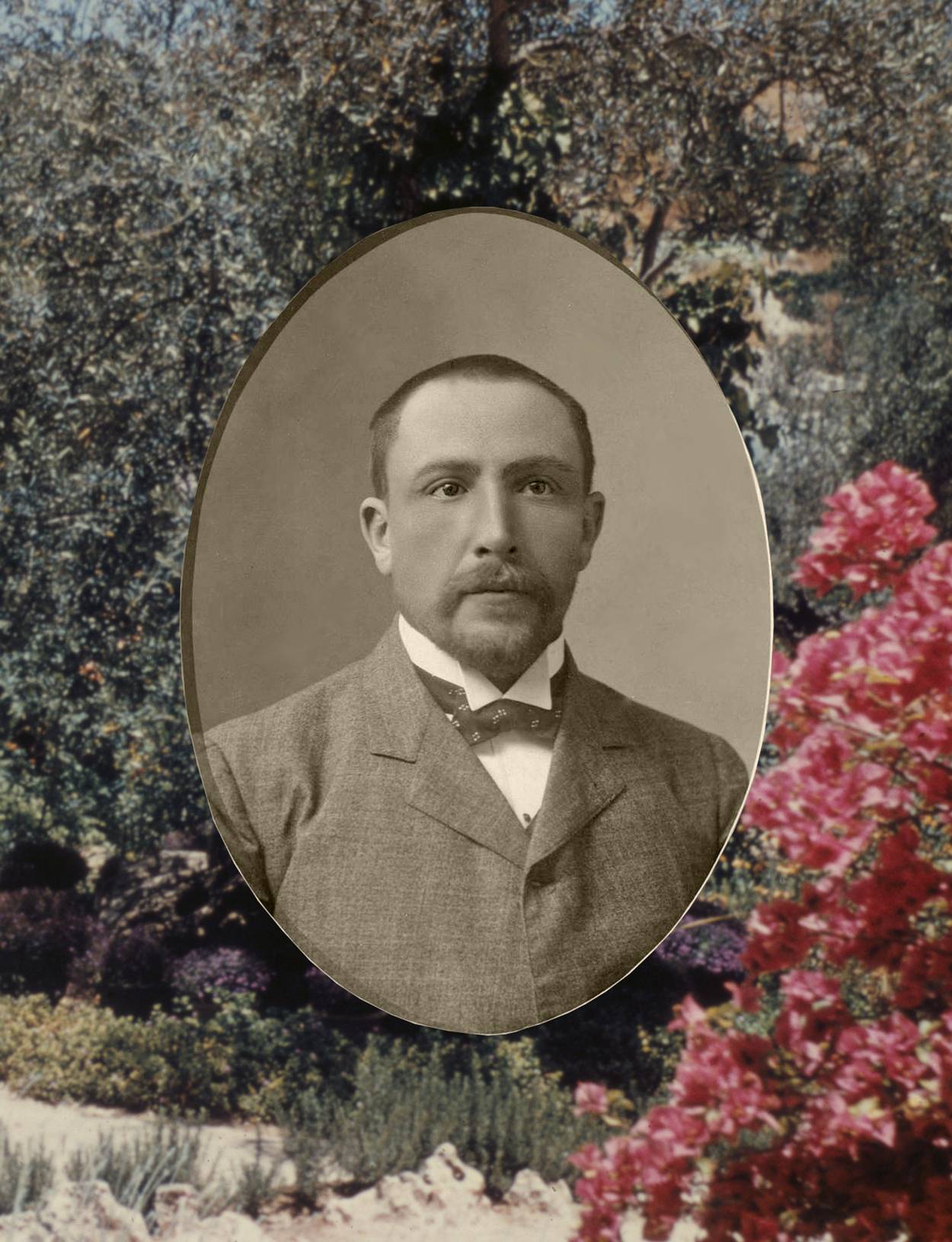

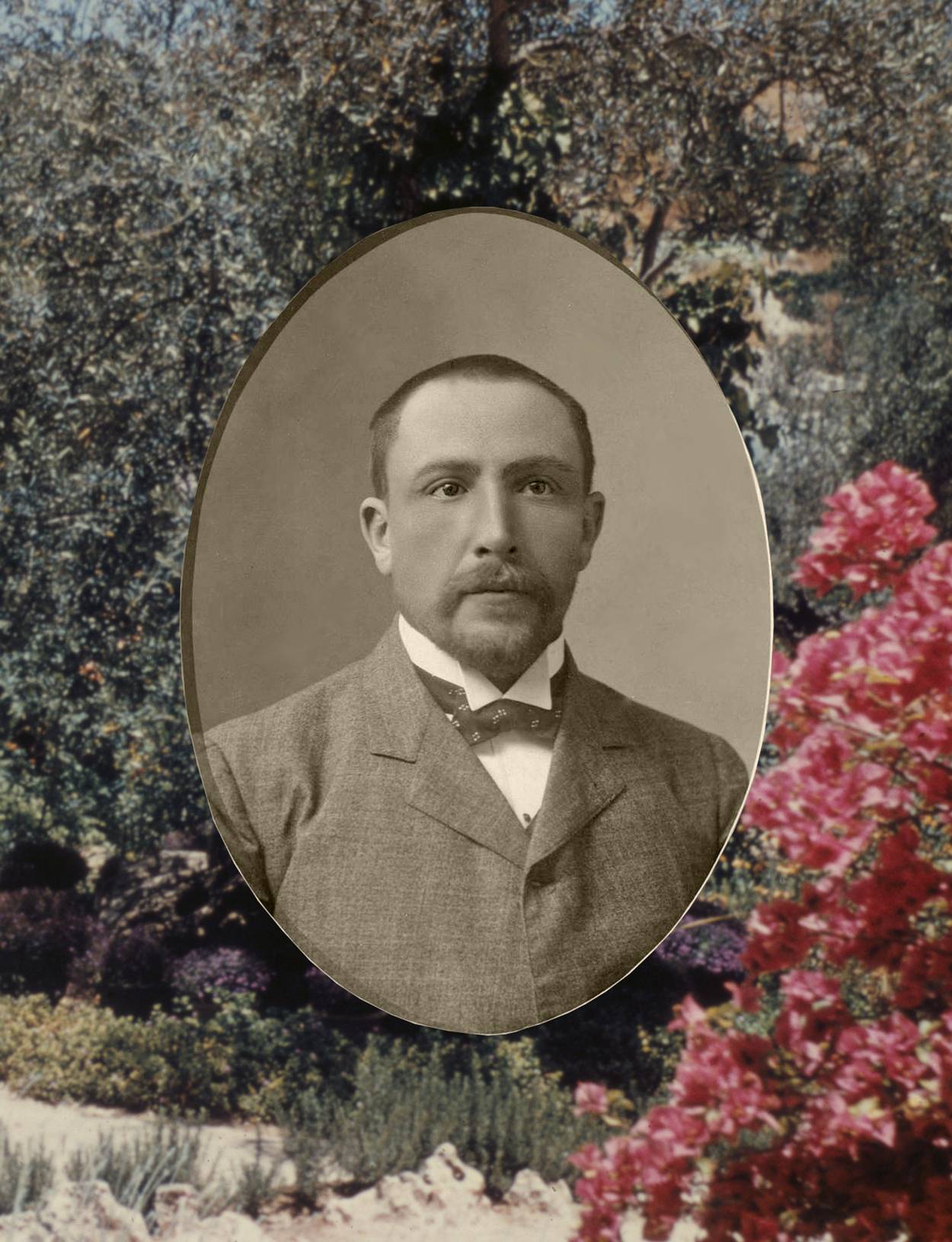

They had assembled in the streets in droves, with raucously youthful excitement. Coming from nine local Hebrew schools, they proudly bore their festive finest, bedecked in blue and white ribbons. Gathering at the request of their Russian-born Pied Piper of an Ivrit teacher, Hayyim Aryeh Zuta, the children planned on proceeding to the village of Motza and planting trees.

Born in Kovno, Lithuania, in 1868, Zuta had landed in the port of Jaffa in December 1903. He brought with him to the yishuv the belief that modern secular subjects be taught alongside traditional religious ones and pent-up dreams of putting down roots in the Jewish national homeland. Recalling in his memoirs how, as a child, he had witnessed a festive spring agricultural festival in Ekaterinoslav (today’s Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine), Zuta lamented:

Blessed is the nation that plants trees in its own land! Alas, the students from my people walk and plant saplings in a foreign soil, where they do not belong, and my heart is mournful!

Perhaps, he surmised at the time, “there, in the land of Israel, the new year for the trees is indeed the 15th of Shevat … and is probably a big deal.”

It turned out that it wasn’t a big deal. The obscure date mentioned in the Mishna as the “New Year for Trees” hardly registered on the public calendar at all.

Until Zuta showed up.

‘Those who plant in tears, will reap in rejoicing,’ said the Psalmist. The tears have been raining for months now.

In 1906, after intense lobbying by the recent immigrant and passionate educator, the organization of Israeli Hebrew teachers inaugurated the now-traditional planting ceremony. So it was that, with momentum built over recent years, in 1913—that is, Tu B’Shevat 5673—Zuta was peaking. Leading masses of youngsters on a path “up to the vineyard of Cohen, the farmer,” to plant saplings, the ceremony culminated in the erecting of a celebratory arch. It received effusive coverage in HaTzvi, the Zionist newspaper published by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the reviver of the Hebrew language.

Zuta’s efforts had actually been inspired, albeit indirectly, by the American celebration of Arbor Day. On April 10, 1872, J. Sterling Morton of Nebraska, who served as President Grover Cleveland’s secretary of agriculture, organized the planting of around 1 million trees in his state. Within a couple of decades, the plantation festival had caught on globally. It spread to France and Spain, Australia and New Zealand, and the Russian Empire, where it awed the young Hayyim Aryeh.

Alas, that Tu B’Shevat morning in 1914, the expected celebration was just not to be. Midway through the day’s three-hour parade, special blue canvas bags with seedlings clutched tightly in countless tiny hands, the rain began. The students simply could not continue. Shoulders slumped and faces wet with raindrops and tears, they returned disappointed, having never reached Motza.

But by the late 1920s, Tu B’Shevat had more than bounced back from the disaster of 1914. Processions in Jerusalem became a recognized and popular practice. In 1930, the Jewish National Fund distributed a booklet encouraging planting trees to mark the holiday. It included a description of a children’s procession from the Lemel School to the new neighborhood of Beit Hakerem (literally, House of the Vineyard), where that year’s ceremony was taking place:

The yard of the Lemel School is thronged with children, their faces lit with joy. They are crowned with garlands of spring flowers, and flags flutter in the light breeze ... The orchestra at the head of the procession are playing a lively march, but bringing up the rear, we can hear nothing but the drumbeats. All the houses are decorated with branches and flowers and greenery is everywhere, making it abundantly clear that today is a celebration of nature and of growth. The trees wave their foliage, as if to cry, “Welcome, children, young and old. Welcome! Go out and multiply the trees in the land, for salvation lies in its trees and forests.”

Those tiny seedling packets clutched so hopefully by Zuta’s students? A sample currently sits in Israel’s National Library, and is showcased as one of the renowned institution’s “101 Treasures” in the book celebrating the library’s new building. The simple sack of some small, unplanted seeds sits alongside manuscripts from Maimonides, the collected writings of Franz Kafka, and the sole copy of the lyrics to “Hatikvah” signed by Naftali Herz Imber. The unplanted potential, that heartache of youth, reflects the growing pains of a still young country flooded with loss.

This year, on Tu B’Shevat 5784—actually, ever since Oct. 7—most Israelis feel like those Jerusalem children of 110 years ago, buoyancy depressingly drenched and aspirations deferred if not entirely canceled. Those hopeful, halcyon days when husbands were home, local bomb shelters were blissfully unoccupied, and normalization with Saudi Arabia was right around the corner seem now like a shadow of a memory under still dark clouds.

“Those who plant in tears, will reap in rejoicing,” said the Psalmist. The tears have been raining for months now. And the bustle of balancing life, family, and work in wartime hardly leaves time for taking a day to think about trees. The rejoicing will come soon enough, we believe and keep reminding ourselves, even as it tarries and even as we continuously wait for it.

The New Year for Trees arrives once more, and with it the hope that the cries of the cataclysm we are still living through will be replaced by those joyous, prayed-for tears. We seek to march forward and plant yet again, silently wishing that salvation will once more emerge in the trees and forests, multiplying across the land.

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada, which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, Esther in America, Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth and Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.