The Jewish Christmas Musical We Need Right Now

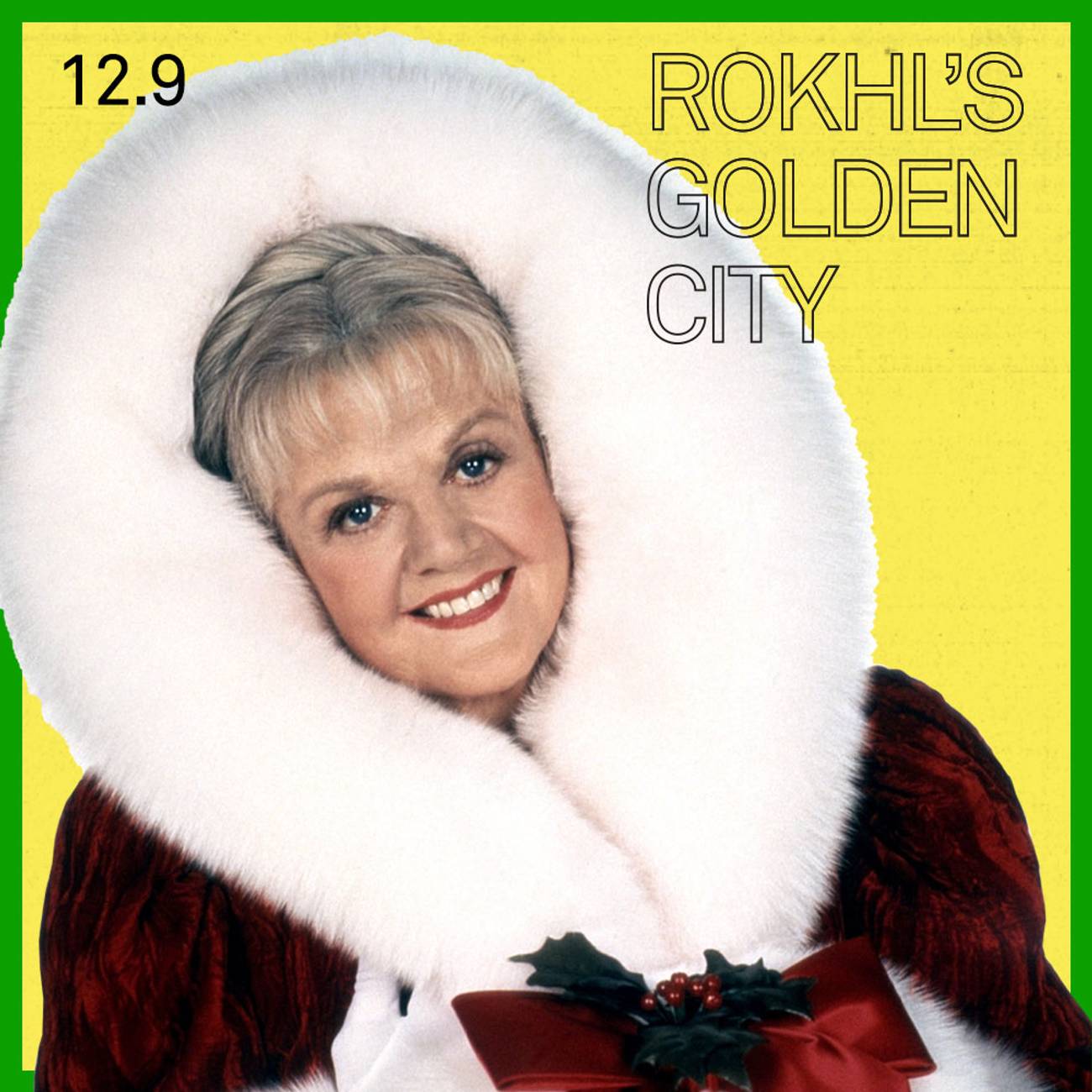

Rokhl’s Golden City: Angela Lansbury’s forgotten 1996 made-for-television movie ‘Mrs. Santa Claus’ is a big, gay, pro-union holiday extravaganza

Christmas in New York. Even a Grinch such as myself will admit to holding certain sentimental associations: the windows at Saks Fifth Avenue, the larger-than-life tree lit up at Rockefeller Center, a neighborhood performance of Handel’s Messiah.

A well-off visitor to New York City of 1900 would have had very different options for Christmas entertainment. One of those was visiting the poor in order to give gifts and food. Such individual visits became popular in the mid-19th century, facilitated by institutions that cared for poor children. By 1900, the Salvation Army was organizing massive Christmas dinners at Madison Square Garden, with some 20,000 hungry people showing up for their free holiday meal, and thousands more buying tickets to gawk from above.

In his superb history of the season, The Battle for Christmas, Stephen Nissenbaum describes how “the hungry and homeless were fed at tables on the arena floor, under the glare of electric lights” while “more prosperous New Yorkers paid to be admitted to the Garden’s boxes and galleries, where they observed the gorging.” The headline in The New York Times said it all in all caps: “THE RICH SAW THEM FEAST.” As Nissenbaum writes, this was charity as spectator sport, an expression of New York’s Gilded Age wealth inequality combined with growing awareness of social problems like poverty, child labor, and drunkenness.

While there were various sociopolitical motivations at work in the Christmas charity spectacles, Nissenbaum argues that we cannot underestimate the importance of the personal and emotional. It wasn’t good enough for the participants to make a monetary contribution from afar. What they craved was the ostensibly “genuine” emotion produced by grateful recipients of their charity, emotional gratification they, especially well-off women, couldn’t get at home.

“The very importance,” Nissenbaum writes, “that domestic life had taken on in nineteenth-century American society had led many people to harbor a set of powerful expectations that real families found difficult to fulfill. The middle-class family was becoming a victim of its own utopian fantasies.”

By the 1910s, the Gilded Age was giving way to the Progressive Era. Popular movements had sprung up to address the problems brought about by rapid industrialization, urbanization, and mass immigration. Child labor, worker exploitation, and public drunkenness all became targets of reform campaigns. The fight for women’s suffrage was being waged in the streets. And it was onto those very streets of 1910 New York (or a studio backlot approximation thereof) where none other than Mrs. Santa Claus (played by the legendary Angela Lansbury) would be fortuitously stranded one December night in 1996.

Yes, in 1996, Mrs. Santa Claus found herself in the most improbable setting for a made-for-TV Christmas movie: New York City’s Avenue A, among the bubbling “melting pot” of that famous immigrant neighborhood. CBS aired Mrs. Santa Claus, the “first original musical written for television since Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella in 1957,” proving, once again, that Dame Angela (of blessed memory) was the total package. Lansbury sings, she dances, and she acts the hell out of what is an inherently very silly role. The script was written by Mark Saltzman and all new songs were composed by Lansbury’s old Broadway collaborator, Jerry Herman. Bob Mackie, Mr. Eighties Glamour, designed the costumes. The result was the gayest, most pro-union, most Jewish Christmas special possibly ever made. It’s the kind of Christmas special even a Grinch like me could love. And after being out of print for years, it’s now available again on DVD and, most importantly, you can watch the whole thing for free on YouTube.

But before I can get to Avenue A, we have to talk about the genius behind the music, Jerry Herman. Herman’s parents were musicians and music teachers for various Catskills hotels and camps and he grew up in the amateur theatrical world that flourished in the mountains. In 1961, he wrote his first real Broadway musical, Milk and Honey, about American tourists hunting for love in Israel. Yiddish theater legend Molly Picon played Clara Weiss, winning raves from The New York Times.

After Milk and Honey came his most famous shows, Hello, Dolly!, Mame (with Angela Lansbury) and La Cage aux Folles. The modern Broadway musical owes much to gay and Jewish and gay Jewish artists. But Jerry Herman may be unique in that he was able to address both of those identities so directly in his work, rather than displacing them onto more palatable Others.

As a Broadway composer and lyricist, Herman made an important contribution to yet another venerable genre: the Jewish-authored Christmas standard. He wrote “We Need a Little Christmas” for 1966’s Mame.

In 1983, Jerry Herman brought an American adaptation of La Cage aux Folles to Broadway, writing the music and lyrics, with a book by Harvey Fierstein. At a time of resurgent homophobia and the Reagan administration’s criminal disdain for the growing AIDS crisis, La Cage presented a happy gay couple with a well-adjusted (straight) adult son. The men, Georges and Albin, live above their drag club in St. Tropez. Conflict arises when their son announces his engagement. His fiancee’s parents, the Dindons, happen to be representatives of the homophobic Tradition, Family, and Morality Party. In French, dindon means turkey (as in the bird) but also has the sense of being a sucker. To be le dindon de la farce is to be someone who is the butt of a joke. It’s a pointed reminder that the people pushing moral panics and scapegoating minorities are dangerous, sure, but in the end, they’re just fools who have devoted themselves to hatred.

In the years after the wild success of La Cage, Herman was less of a presence in the world of musical theater. He learned he was HIV-positive a few years later. In the mid 1990s, his old friend Angela Lansbury became concerned about him. His health was poor and he wasn’t working on his art. So, she conceived a plan whereby CBS would fulfill a contractual obligation to her, producing a television movie in which she would star and he would create the songs. Here, one of my favorite YouTubers, Matt Baume, tells the whole story. It was from Baume’s video I first learned of the existence of the wonderfully wacky Mrs. Santa Claus:

Let’s first stipulate that Mrs. Santa Claus has all the dramatic tension of a string of popcorn. And that’s fine. This is the only Christmas special I’ve ever seen, but I’m assuming that people like them because they’re comfortable, not because they’re taut thrillers.

We meet Mr. and Mrs. Claus at the North Pole workshop, where a new batch of children’s letters means they will have to work overtime. Head elf Arvo is played by another Broadway legend, Michael Jeter. Mrs. Santa Claus tries to talk to her husband, explaining that she has a new map that will improve the efficiency of his Christmas Eve route. Unfortunately, Santa (Charles Durning) is too preoccupied to listen. Right away, the script brings in two important Progressive Era themes: women’s participation in the workplace, as well as scientific solutions to the problems of industrialization.

This Santa isn’t really a bad husband, he’s just too wrapped up in his work to be present for his wife. But Mrs. Claus is impatient to see her new delivery route tested. She impulsively takes the reindeer out for a spin. But an injury to one of the reindeer strands Mrs. Claus on Avenue A. Because she is so kind and talented and cheerful, she makes friends everywhere she goes. Soon, she is guided to a boarding house run by Mrs. Lowenstein, played by Rosalind Harris, who played Tzeitel in the Fiddler on the Roof movie. Tzeitel is all grown up and in America, a widow, with a feisty daughter known to the neighbors as Soapbox Sadie.

Perhaps the most important moment in the movie happens toward the beginning. We see Mrs. Claus walking the spacious streets of this backlot Lower East Side. On her way to Lowenstein’s boarding house, she peers in at what is presumably a shul, where congregants perform an enthusiastic, if not terribly authentic, “Jewish” dance. Mrs. Claus (now known as Mrs. North) is agog.

At the boarding house, Mrs. Lowenstein tells Mrs. Claus that they will be having latkes for dinner. Just as Mrs. Claus celebrates Christmas, so do the Lowensteins celebrate Hanukkah. It’s a moment that could, and, in a psychologically accurate Mrs. Claus story, would, shake our feisty protagonist, earning at least a couple more dramatic beats. If there exist people in the world who don’t believe in the sanctity of the Claus marriage, who don’t celebrate Christmas or believe in its magic, surely that should flap our unflappable protagonist, if not precipitating a full-blown epistemic crisis.

And yet, she takes this earth-shaking news in stride. She isn’t bothered or threatened by people who don’t believe in her magic. She just continues to do what she always does, offering her sincere friendship and endless ingenuity. This is what it means to be an ally.

Later on, Mrs. Claus takes a job at a sleazy toy company. The toys are dangerous and defective, and Mr. Tavish cruelly exploits his child workers. Inspired by Sadie Lowenstein, Mrs. Claus organizes the child workers for a labor slow down. Even after they sell her out to the boss, she continues with her plan to save them. In another classic Progressive Era theme, she sets about exposing the conditions of the toy factory and rousing the people against Tavish’s exploitive ways. All of this, of course, accomplished through classic Broadway song-and-dance routines.

In the end, of course, Santa and Mrs. Claus are reunited. I’ll admit, I got just a teeny bit choked up at Charles Durning’s tender song for his missing wife. The movie’s song and dance numbers are delightful, if not quite Broadway gold. But what I found so fascinating were the values at play. Though the reunion of Mr. and Mrs. Claus provides dramatic resolution, the movie is very much about her journey into the wider world, where she finds a new community and new purpose to her life. Mrs. Claus finds joy in mutual aid, in stark contrast to the Gilded Age spectacles of charity described by historian Stephen Nissenbaum.

She aids the children laboring in the toy factory, not as a benevolent social worker-savior (as was the model for many women of that period) but as a fellow worker. And rather than being shaken to find people who do not share her particular beliefs, she is in fact strengthened by it. What makes things right in the story is not the return of a wayward wife to her home, but the discovery of new forms of kinship and collectivity. I dare say, I finally understand the meaning of made-for-television Christmas miracles.

ALSO: The Man Without a World is a silent film that will be screened with a live musical accompaniment by Alicia Svigals and Donald Sosin. I’ll be taking part in a discussion after the film. Dec. 22 at the Museum of Jewish Heritage. Tickets here … If you prefer your Christmas a little more serious than Mrs. Santa Claus, join David Biale for A Very Jewish Christmas: Jesus and Shabbtai Zvi, From Heretic to Hero. Dec. 22, more information here … YIVO is once again offering a stellar lineup of January classes. Check out the full list here … The Yiddish New York festival officially starts on Dec. 24. There’s still time to get your tickets and festival passes. Many classes and events will have a virtual-remote option. And forgive me for yet another gentle reminder: At the Dec. 28 Dreaming in Yiddish concert your humble columnist will be receiving the Adrienne Cooper Dreaming in Yiddish prize! Hope to see you there!

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.