The Rise of the Yom Kippur Appeal

Why synagogues turned away from weekly ‘shnuddering’ and adopted an annual donation campaign instead

Courtesy Rabbi Michael Strassfeld, photo: Cole Wilson

Courtesy Rabbi Michael Strassfeld, photo: Cole Wilson

Courtesy Rabbi Michael Strassfeld, photo: Cole Wilson

If ever there was a Rube Goldberg-esque contraption connected to the synagogue, consider the Alyias Donation Book. A cross between a computational device and a children’s book, it was composed of paper flaps, ribbonlike strips of linen, and rows of columns rendered in both English and Yiddish lettering. Its purpose was to record the name of a donor and the amount donated without using a pen or a pencil: peek-a-boo alchemized into peek-a-pledge. As Kestenbaum & Co, of 41 Delancey Street, New York, N.Y., its manufacturer and distributor, explained, this distinctive product “eliminat[ed] writing on Sabbath days and Jewish holidays.”

The Alyias Donation Book, copyright 1930, was designed to solve a problem: how to raise money on the Sabbath without coming into physical contact with it, lest the sanctity of the day be violated and marred. Or, more to the point, how to raise money on the Sabbath and remember who made a contribution and in what amount so that, in the course of the week, said contributor might be contacted and reminded, lest honoring his pledge slip his mind.

The purview of the synagogue’s sexton or shamas, the equivalent of his little black book (except this one wasn’t so little; when opened, it measured 26 inches wide and 15 inches long), it called on him (or “the person operating this book”) to maneuver the strips up and down and across so that their letters would properly align to form the name as well as the address of a donor and their numbers would properly align to reflect the exact amount of his contribution. The whole would then be manipulated into position to correspond to a specific honor, say the sixth aliyah to the Torah, and to record in whose name—the rabbi’s, the cantor’s, the sexton’s, or that of some other person, entity, or occasion—said contribution was made.

No longer in use, the Alyias Donation Book is, these days, the treasured property of Rabbi Michael Strassfeld who, over the years, has assembled a marvelous collection of American Jewish religious and cultural objects. It, along with two kindred objects in the collection, shed light on an aspect of synagogue life that doesn’t usually receive much play: maintenance. The Alyias Donation Book keeps company with a second volume, a spiral notebook whose pages made use of tiny metal arrows and row upon row of paper sundials composed of letters and numerals to record donor and sum.

Courtesy Rabbi Michael Strassfeld, photo: Cole Wilson

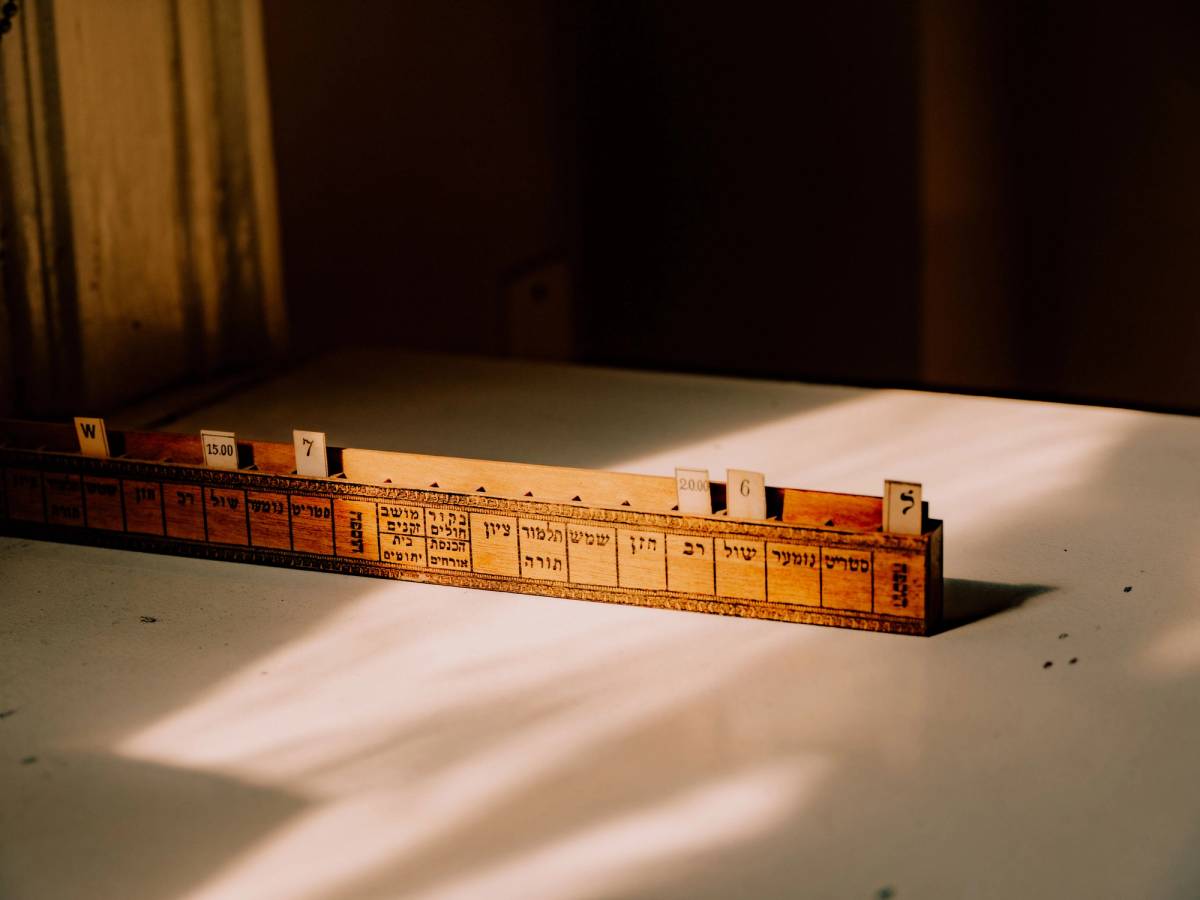

Rounding things out is a handmade, elongated wooden box that contained a set of at least six, possibly more, individual wooden pieces that bring to mind either the tile holder used in Scrabble, or a miniature mailbox. Tiny slots run the length of every 13-inch-long piece, each one marked by Hebrew words designating the recipient. One, for instance, was marked, “shul,” another “Tzion,” a third “Bikkur Holim.” Equally tiny paper slips with printed Hebrew letters or numerals would be inserted into each slot to document the donor’s name, the scale of his contribution, and its destination.

All three objects intrigue as much as delight, raising questions about their makers as well as the circumstances of their creation and use. Who was responsible for moving the linen strips and the metal arrows, and filling in the slots? And at what point during or after the proceedings were they activated? We just don’t know, which adds to their mystique.

What we do know is that within traditional circles of the early 20th century, fundraising in the sanctuary was not limited to Yom Kippur—as, thankfully, it is today—but was a weekly affair. Any time anyone (read: any male) received a kibbud, or an honor, on Shabbos morning or on a yontef, especially if it took the form of an aliyah to the Torah, he was expected to make a monetary contribution in return, and to have the amount announced in a sufficiently loud voice so that everyone present might learn of his generosity. In another variation, usually associated with the High Holidays, communal honors would be auctioned off to the highest bidder. This customary practice was known as “shnuddering,” an Anglicized conflation of the Hebrew word she-nadar, or “he who made a pledge or a vow.”

The much-rued Yom Kippur appeal turns out to be one of the legacies of the often rose-tinged immigrant generation.

At the time, traditional congregations depended on shnuddering as a steady source of revenue. Then, as now, dues didn’t stretch nearly far enough to cover all the expenses, from salaries to supplies, associated with running even the most modest of religious institutions. Those in charge of finances relied on this informal monetary transaction to keep their institution, and its clergy, afloat.

Its social function was nearly, if not just, as significant. Congregations depended on shnuddering to know who was up and who was down, who was stalwart and true, apt to made good on his pledge, and who was given to grandstanding and defaulting on, or deferring, his pledge. The size of the donation Moshe made in honor of the rabbi and Yankel made in honor of his wife, Chanele, alerted everyone in the pews as to whether Moshe and Yankel were doing well (or wanted to appear as if they were), or had fallen on hard times. Shnuddering, then, was at once a barometer and a declaration of status.

Despite the this-world associations, the practice had more than a whiff or two of sanctity about it; actually, “inviolability” might be an even better word. It’s not that shnuddering had the force of Halacha, of Jewish law, for it did not; its authority was derived from minhag, or custom. But as anyone who has ever tried to mess with a domestic, institutional, or a local minhag will tell you, it functions as if it does. Shnuddering was not to be touched.

Still, there’s no getting away from the fact that it was an intrusive practice that disturbed Shabbos morning services, interrupting the flow of the Torah reading, much less the flow of higher thoughts. At that one moment during the week when shulgoers might possibly be attuned to something higher than the costs of fixing the boiler or paying for the next shipment of coal, the steady accumulation of bulletins from the front about monetary contributions brought them down to earth with a thud.

When these two cultural systems—commercialism and sanctity, the holy and the profane—collided, which increasingly they did in modern America, things could get nasty. Shnuddering gave rise to many a communal tussle when either the new rabbi in town or several congregants of a refined sensibility proposed at the next board of trustees meeting that the practice be abolished. All hell would break loose. Tempers flared so hotly you’d think abolishing the Torah reading was on the table.

Courtesy Rabbi Michael Strassfeld, photo: Cole Wilson

Those in favor of bidding farewell to the practice couched their petition in terms of decorum, advocating its civilizing effects on the body politic; those opposed insisted that its abolition, the first chink in the armor of tradition, led directly to Reform, a trajectory that was not to be contemplated.

Congregants in the first camp had sociology on their side. A more decorous service was unquestionably a quieter, more contemplative affair. With fewer disruptions, it was likely to hew New World than Old, itself a most welcome development. Those in the other camp had history on their side. Since one of the first things the European founding fathers of Reform Judaism did was to abolish shnuddering, those who fretted about the future of traditional Judaism in America had cause to worry when the issue came up on their side of the Atlantic.

The dueling perspectives made for an impasse, which synagogue minutes referred to time and again, especially when the process of change was a protracted one. At Manhattan’s flagship Orthodox congregation, Kehilath Jeshurun, it took 40 years—yup, the biblical 40—before the powers-that-be could see their way clear to bidding a final farewell to shnuddering. During that stretch of time, a number of “innovations” designed to heighten decorum were implemented—among them, ushers to keep the peace and singing in unison—but shnuddering stayed the course and remained.

When, at long last, at Kehilath Jeshurun and elsewhere, the practice became one with the spittoon and the snuff box, vestiges of yesteryear, nothing untoward resulted: no rush to the exits, no decrease in membership, no quaking heavens.

At most, shnuddering’s retirement prompted congregations to come up with alternative forms of fundraising to compensate for the deficit created by its absence. Enter: the Yom Kippur appeal. What a rich irony that the elimination of one form of Jewish fundraising gave rise to another and that the much-rued Yom Kippur appeal turns out to be one of the legacies of the often-rose-tinged immigrant generation.

Shnuddering hasn’t entirely vanished—it’s still done in many a shtiebl, especially on the High Holidays—but, over time, the practice became increasingly marginal to how most self-consciously modern American synagogues conducted themselves. With fewer and fewer American Jews able to make heads or tails out of the Alyias Donation Book or its ilk, fewer and fewer copies were produced.

Thanks to the timely intervention, dedication, and keen eye of collectors such as Rabbi Michael Strassfeld, a scant few artifacts of shnuddering have managed to survive, gifting us with the capacity to contemplate the inventiveness of the yidishe kop.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.