A Second Purim Story

Megillat Saragossa tells a tale that parallels the Book of Esther

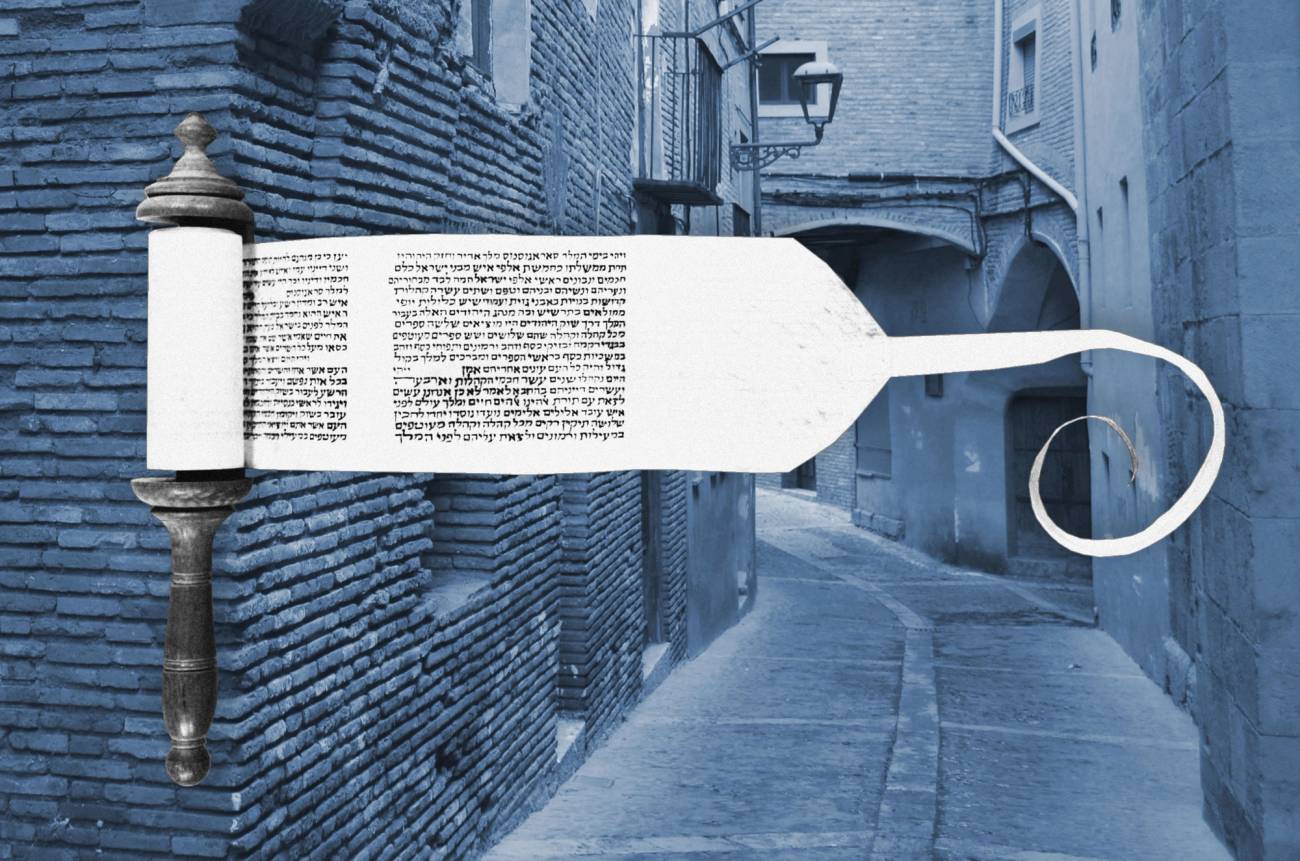

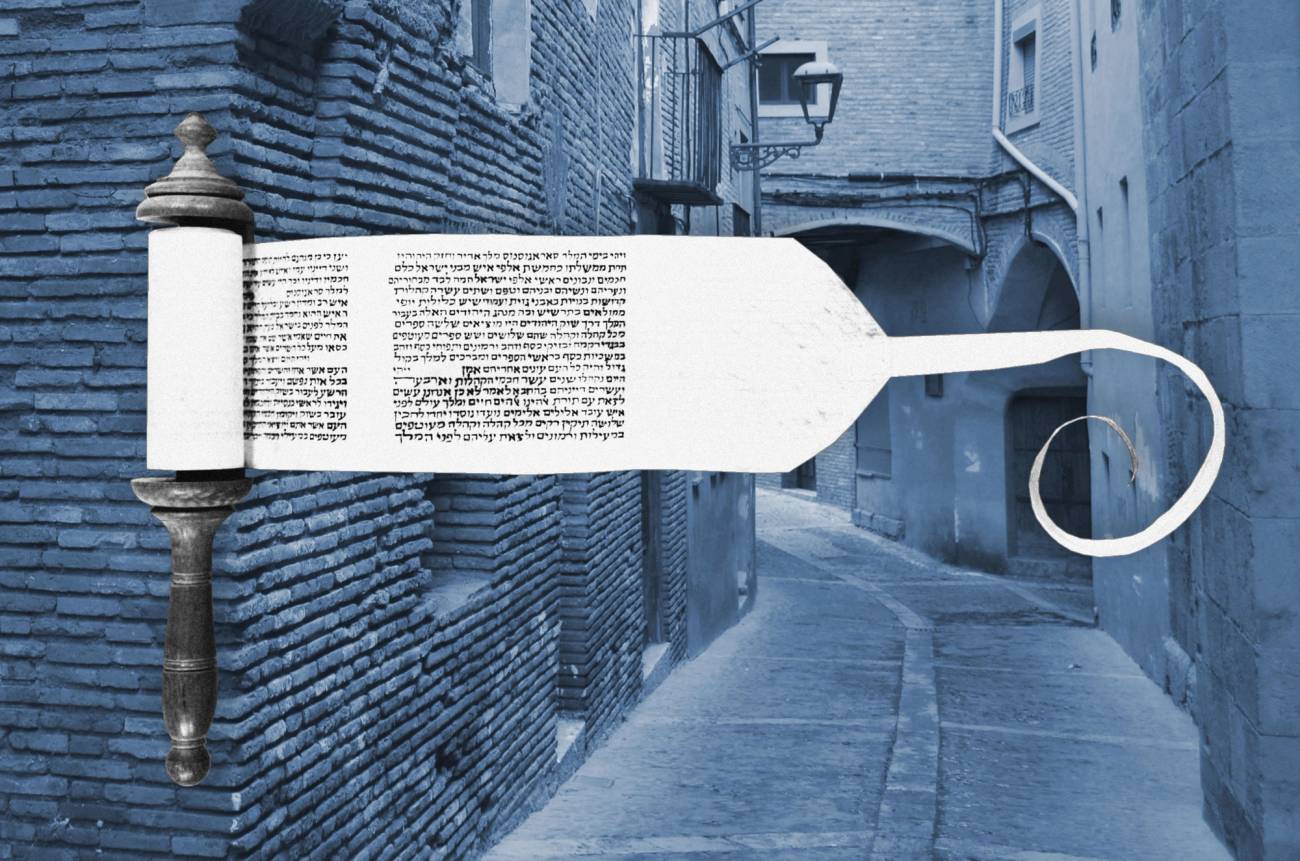

It happened in my undergraduate days that I first saw Megillat Saragossa in Columbia University’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library. A small, yellowed scroll mounted on a simple wooden handle, the old parchment unfurled to tell the story of a diasporic Jewish community on the verge of destruction. However, the Jews in this tale were not living in ancient Persia under the reign of King Ahasuerus while evil Haman plotted a genocide that Queen Esther and Mordecai managed to thwart. Instead, Megillat Saragossa relates the plight of medieval Jews narrowly avoiding the wrath of their gentile ruler (and a malicious tattletale) with the help of Elijah the Prophet and a pious beadle. The Jews of Saragossa recorded the story to celebrate their narrow escape centuries ago, and their descendants annually return to the scroll to commemorate a Second Purim.

I, too, returned to see the scroll. The concept of a Second Purim—invoked quite commonly among medieval Jewish congregations throughout Europe and North Africa—baffled me. I could not understand how a single city felt confident enough to inaugurate its own local Jewish holiday. To form a consensus of this kind, people must be strongly united. It’s hard to imagine any Jewish community today mustering up the pluck to pen a 21st-century Purim tale.

Holding the 17th-century megillah in my hands, I felt the tension between the sturdy parchment and the umbilicus; the scroll was unused to being unrolled. The scribe—likely a descendant of the original Jewish community of Saragossa—had pricked and ruled 17 neat lines onto which he had written the Hebrew text. The handwriting was square Spanish script, without taggin, the crowns that are a scribal feature on holy Jewish texts, and the black letters gleamed as though the ink had not yet dried. Beyond the physical beauty of the artifact, Megillat Saragossa is proof that the medieval Jews felt so connected to their heritage that they not only viewed their contemporary event as worthy of remembrance, but considered their circumstances significant enough to narrate their story in the style evocative of the original Megillat Esther.

While certain clues about the historical tale can be found in the text, debate surrounds the exact date and location of the Purim of Saragossa. For instance, scholars argue whether the miraculous salvation occurred in 1380, under the reign of Peter IV of Aragon, or 1420, when Alfonso V of Aragon ruled. (The king’s personal name is never mentioned in Megillat Saragossa.) The place is referred to in the text only as Saragossa; some maintain this refers to the city of Saragossa in Spain, also known today as Zaragoza, while others say the story took place in Syracuse in Sicily, in part due to its phonetic similarity. Despite the doubt surrounding the details, the acceptance of the story is certain: As the progeny of the Saragossa Purim traveled, their celebration was adopted by many communities along the Mediterranean.

Invoking the same style, structure, and archetypal figures of the Book of Esther, Megillat Saragossa sounds strikingly similar to the first Purim story. Opening with the line, “It happened in the days of King Saragossanos,” Megillat Saragossa alludes to its predecessor’s renowned introduction. Both scrolls richly describe the affluent settings of their stories: The garden of King Ahasuerus’ court was filled with marble pillars draped with the finest blue, purple, and white linens, and the Jewish community of Saragossa similarly boasted ornate architecture, including “hewn stone and marble pillars, studded with beryl.” The most prized possessions of the Jews in Saragossa were their Torah scrolls, which were wrapped with embroidered cloth and encased in “silver and golden coffers” adorned with showpiece apples and pomegranates.

Custom dictated that when the King of Saragossa visited the Jewish marketplace, the community would bring out the Torah scrolls in their beautiful cases and bestow blessings on the monarch. Eventually, the sages became concerned that presenting their holy Torah scrolls to a gentile king was sacrilegious. Secretly, the scrolls were removed from their cases. When the king visited, the Jews displayed the empty Torah cases and blessed him just the same.

But danger loomed. In the same manner that the wicked adviser Haman climbed the ranks and convinced King Ahasuerus to seal the fate of the Jewish people, a man named Hayyim Sami—who converted away from Judaism and assumed the name of Marcus—was promoted by King Saragossanos within the royal court. Marcus informed the king that the Torah cases were kept empty, insinuating that disrespect and disloyalty were rampant among the king’s Jewish subjects. A fury not unlike the murderous rage that preceded Vashti’s removal burned within the King of Saragossa, who handed over his signet ring and a death sentence for the Jews if Marcus’ claim turned out to be true.

That night, it was the beadle Ephraim Baruch who simply could not sleep. Elijah the Prophet appeared to Ephraim Baruch, urging him to replace the Torah scrolls in their cases. The following day, on the 17th of Shevat, the king entered the Jewish marketplace with 300 armed men, eagerly gripping their swords, and demanded that the coffers be opened. The Jews waited with bated breath. Every case was opened, and the Torah scrolls were—thankfully, miraculously—inside.

Not only were the Torah scrolls present, but each was opened to the verse in Leviticus 26:44: “But despite all this, while they are in the land of their enemies, I will not despise them nor will I reject them to annihilate them, thereby breaking My covenant that is with them, for I am the Lord their God.” Referencing this Torah portion, the message the composer of Megillat Saragossa made is clear: God does not forsake the Jewish people, even when they are exiled in the land of Saragossa.

Marcus ended up hanging from a tree on the command of the king—precisely like his evil forerunner, Haman. To rejoice in their salvation, the Jews celebrated with feasting, gave gifts to friends and charity to the poor, and recited Megillat Saragossa, newly composed in commemoration of the miracle.

Today, there are roughly a dozen cataloged Megillat Saragossa scrolls, all written ex post facto, located within various institutions in the United States, Israel, France, and Turkey. Columbia University holds two scrolls, gifted at the turn of the 20th century by Richard Gottheil, professor of rabbinic literature and Semitic languages. Michelle Margolis, the Norman E. Alexander librarian for Jewish studies, showed me both: the 17th-century parchment scroll—which I held in my hands—and the 18th-century scroll, which was written on paper and has since faded and crumbled, now too delicate to unravel.

The impulse to record our stories in a style imitative of the Jewish canon has largely disappeared. After all, writing ourselves into history is no easy feat. A community cannot blandly recite that they are a link in the long chain from Mount Sinai; they must believe it. While this may feel unnatural for contemporary congregations, the psychology of medieval Jewry was wired for this connection. As Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi writes in Zakhor:

[M]edieval Jewish chronicles tend to assimilate events to old and established conceptual frameworks … [T]here is a pronounced tendency to subsume even major new events to familiar archetypes, for even the most terrible events are somehow less terrifying, when viewed within old patterns rather than in their bewildering specificity. Thus the latest oppressor is Haman, and the court-Jew who tries to avoid disaster is Mordecai.

The application of age-old archetypes hasn’t disappeared: Many people consider Hitler to have been of an Amalekite strain. But even if we draw metaphorical language from the canon, we are not imagining ourselves within it the way medieval Jewry did.

When Haman slandered the Jewish people to King Ahasuerus, he described them as “a certain people scattered and separate among the nations.” Medieval Jewry may have been geographically scattered and forcibly separated from interacting with the gentile world due to antisemitic laws, but within their own locales, they were not separated from one another. Today, we are more universalized than ever before—constantly updated on every news event happening halfway across the globe—but we are mentally scattered, emotionally removed, superficially scrolling. While human instinct demands that we bond briefly over tragedies, our Jewish community requires much deeper coalitions to celebrate averted ones.

The original Purim story famously makes no mention of God, which many interpret as a sign that diasporic Jews must pull themselves up by their bootstraps to find the divine in the darkness. In Megillat Saragossa, however, God’s name appears multiple times. The text insists that the Jews of Saragossa are God-fearing and God-following. More importantly, these mentions of a divine presence assure its audience—Jews of Saragossa and their descendants—that God has not abandoned them.

The two Purims don’t coincide on the Hebrew calendar: The Saragossa Purim falls on the 17th of Shevat, almost a month before Purim, which falls on the 14th of Adar. But all the mitzvot of the original Purim are fulfilled on the Second Purim as well: megillah reading, feasting, gifting mishloach manot, and giving charity. Some people even fast the day before. Scholars report that the Purim of Saragossa was celebrated in several Balkan communities into the 20th century and lasted for the longest time in Jerusalem. Most recently, in 2016, Albert Haim Samuel bequeathed the Megillat Saragossa he had received from his devout Izmirian grandmother Deborah—which is written on buckskin leather—to the Neve Shalom Synagogue in Istanbul. While the Samuel family had privately celebrated the holiday for years, Chief Rabbi Ishak Haleva declared that “as a [Turkish] community we would very much like to celebrate Purim Saragossa every year.”

This year, on the 17th of Shevat (the eve of Feb. 7, 2023), cantor Isaac Gantwerk Mayer performed a livestreamed reading of Megillat Saragossa on YouTube. Hearing the words chanted in the familiar cantillation of Megillat Esther brought the text to life in a way I had not anticipated. It was like hearing past generations tell their own story through the same song: Transcending time and space, the original Purim and the Purim of Saragossa rhymed and overlapped, adding layers of nuance to an already rich Jewish narrative.

Chaya Sara Oppenheim is editor of The Shekel, a numismatic journal. She holds a B.A. in English and history from Barnard College.