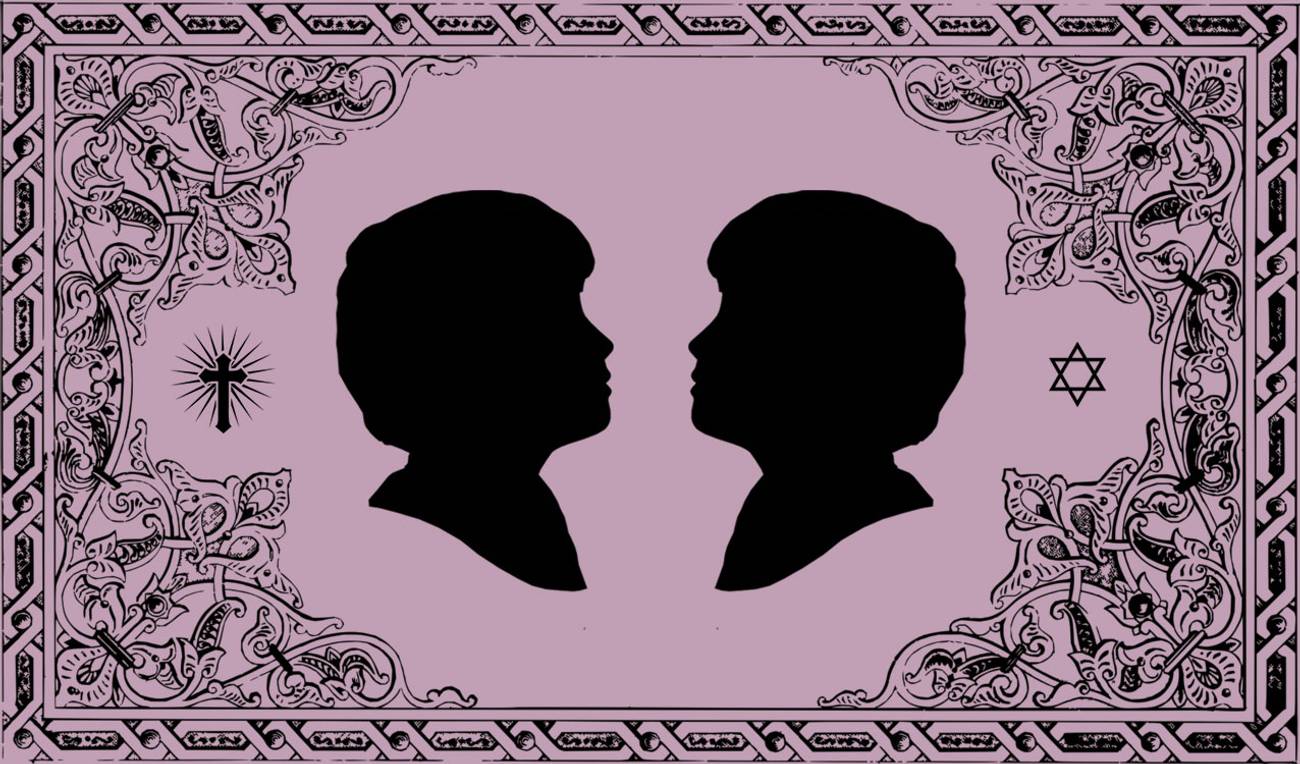

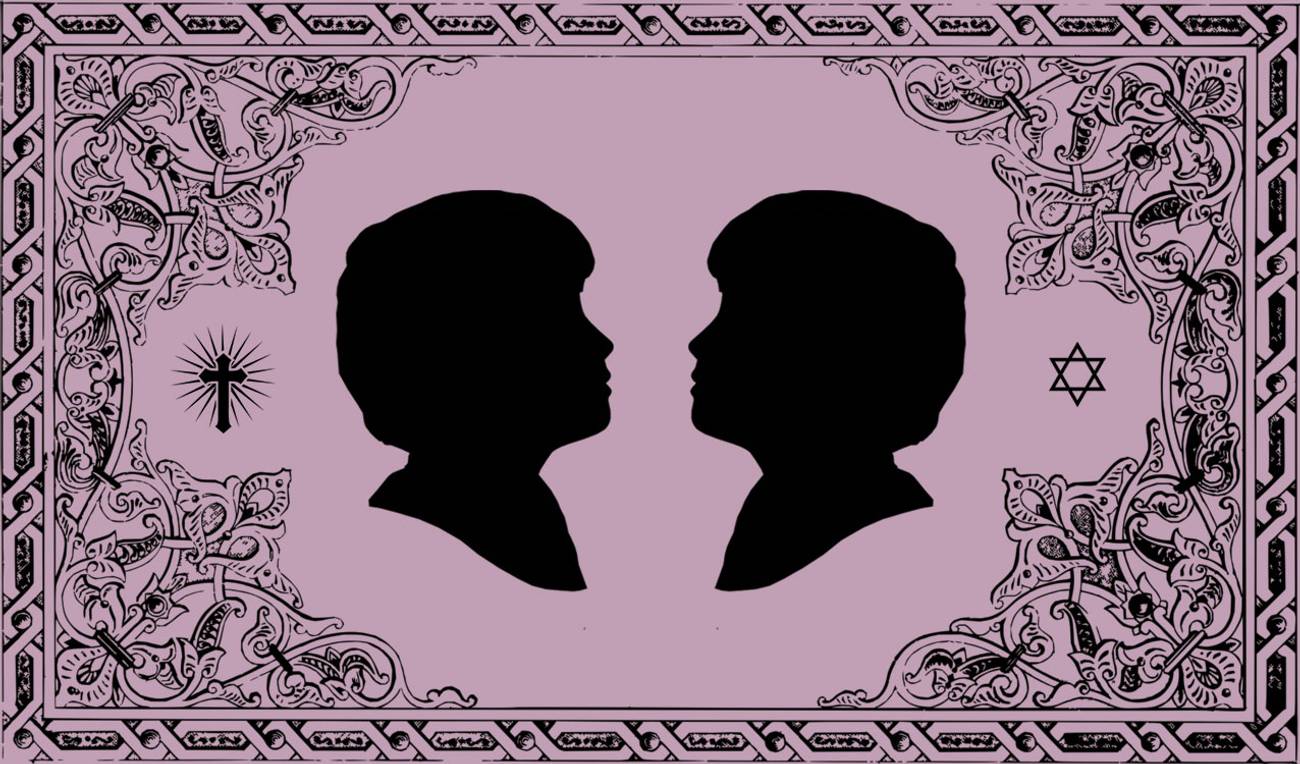

A Tale of Two Atonements

Why I couldn’t forgive my brother as a Christian—but could ask his forgiveness as a Jew

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

I was with my family at the 1976 Montreal Olympics. I was 12. The five of us—my parents, my two brothers, and I—were moving through a carnivalesque square full of people and vendors outside the stadiums when we passed between two groups of religious enthusiasts, one dressed like hippies that my oldest brother said were “Jesus freaks,” the other wearing orange robes, dancing and playing tambourines: Hare Krishnas. My parents and brothers drifted toward the Krishnas. I wandered over to listen to the Jesus freaks.

I was a Christian but not an especially religious one. I had been raised in the Trinity Lutheran Church, in a type of faith I used to describe as Catholic in black and white, meaning we were strong on belief but short on show. I didn’t yet know about my parents—that they were born and raised as Jews, had survived the Holocaust, and had converted to Christianity, partly out of sympathy but mostly out of fear. I’d find out about that a year later when my father would sit down with me one morning and tell me the tale, but that’s another story.

I can’t remember exactly what the hippie preacher preached. I do remember him making a crack about the guys wearing orange and dancing with tambourines. But he also spoke about God and love and building a life around the teachings of Jesus, and I found it inspiring, was sincerely caught up in the enthusiasm. But when he was done, and I looked around for my family, I found myself alone in the throng.

I was scared, but I didn’t panic. I went up to one of the nice Jesus freaks, and he got on the microphone and announced I was looking for my parents; they didn’t show up. So, I waited with him, and we talked about God. He asked me if I wanted to pray with him. It was a strange idea to me, to worship out in the open like that, but I said OK. I was too embarrassed to pray out loud, so he spoke for both of us, asking Jesus to help me find my parents and to help me find Him. I felt safe with the Jesus freaks. I felt loved. I felt like I had maybe found an answer to all my problems, the problems of a depressed little kid.

What did I have to be so sad about? Certainly not my living conditions. My parents were both doctors. We had a nice big house in White Plains, New York, with a Mercedes in the driveway and a brook running in the backyard. We could afford to go skiing and to the Olympics. There were, as far as I knew, no tragedies in my family (I didn’t yet know that three of my four grandparents and my uncle were murdered before I was born). My brothers and I had everything we needed—except our parents’ attention. My mother made more of an effort but was emotionally withdrawn. Neither shared any physical affection with us beyond a routine goodnight kiss. I don’t remember either of them ever so much as putting an arm around me. And they left me alone—a lot.

Some of that had beneficial side effects. Early on, I became resourceful. When I was in seventh grade, for example, I got myself a therapist without even telling my mother (who was a psychiatrist). And by the time I was 12, I could confidently navigate public transportation on my own, which is why, eventually, I told the kindly Jesus freak I could find my way back home. We had been in Montreal for maybe a week, and I knew the Metro system by then.

He gave me some pamphlets and let me go, and I did, indeed, find my way back to where we were staying. And as I rode those shiny, rubber-tired Montreal subway trains, I felt I had embarked on a new life, one centered on God and Jesus and the teachings of the Bible. I would be like those kindly, joyous Jesus freaks. I wouldn’t be unhappy anymore.

I sat down on the hard plastic seat to read one of the things the Jesus hippie gave me and learn more about the Christian way of life I was going to lead. What, exactly, would it mean to follow the teachings of the Lord? One thing the pamphlet said it would mean was forgiveness. Jesus forgave our sins, and I, too, would have to forgive. And that’s where I hit the wall.

I was the youngest of three brothers. The oldest was six years older than me, and we didn’t interact a whole lot. But the next oldest, “my middle brother” as I used to call him, was less than three years older, and he was a cross I had borne for as long as I could remember.

He was, in the grand scheme of things, not so bad. But he tormented me in the small ways big brothers often do. He teased me for being fat. He made fun of me whenever I didn’t know something. And he mocked the way I talked, my Elmer Fudd accent—pronouncing R’s like W’s, a speech impediment I didn’t grow out of until high school. Putting all that in print, it doesn’t seem to add up to much, but at the time it was more than I could take. He wasn’t the source of my childhood sadness, but he made it just a little worse than it might otherwise have been, and I couldn’t forgive him that, especially when I knew that forgiveness would do nothing to stop him from teasing me. And when I realized that, my time as a Jesus freak was over.

“You shall not hate your brother in your heart,” God says to the Israelites, and I didn’t hate my brother, but I couldn’t forgive him until he stopped picking on me and said he was sorry. Of course, he was only 15 at the time and had problems of his own, having been raised in the same troubled family. But eventually, when we were older, he did apologize. I don’t recall if he formally asked forgiveness, but he said he felt bad about how he had been when we were kids. And his actions showed he was a different person, and so I was able to forgive, and we established a friendship; throughout my adult life I’ve looked to him for advice and support. But strangely enough, that inability—or unwillingness—as a child to forgive him kept me from being saved as a Christian and saved me for forgiving as a Jew.

It was erev Yom Kippur, 2005, and I was at the Kotel on the last leg of a monthlong trip to the Holy Land to research a novel I was writing—a “gnostic midrash” based on the Book of Acts. Decades after learning about my family’s Jewish heritage, I still considered myself Christian but was trying to work some things out in the wake of my father’s death the previous year.

The Western Wall was not as carnivalesque as the Montreal Olympics, but once again, I found myself between two groups of religious enthusiasts, albeit smaller ones: two bareheaded young men in jeans, and two men of about the same age wearing black suits and fedoras. The former were evangelizing Christians, the latter yeshiva bochurs (though I didn’t know that term at the time).

“This is the holiest place in the world for Jews on the holiest day of the year,” said one of the men in black. “You don’t belong here.”

“That’s exactly why we do belong here,” said one of the Christians.

A third bochur in black who, like me, was eavesdropping, turned to me. “Can you believe these guys?” he asked, indicating the Christians.

I said I could see both sides and told him my background. “Oh,” he said, “you’ve got to meet a friend of mine.”

God saved me from being saved so that, among other things, decades later, I could ask my brother’s forgiveness as a Jew.

He introduced me to Jeff Seidel, a guy famous for practicing kiruv at the Kotel, and Seidel told me to come back the next day for a class at a synagogue in the Jewish Quarter.

In short, where the Jesus freaks failed, the frum guys succeeded. When I got home to Chicago, I began learning with a rabbi. He set me up with a family who had me over for meals and mentored me in observant Judaism, and not long after that I found myself at Mount Sinai for a long overdue procedure. It wasn’t a conversion (an Orthodox posek said that wasn’t necessary), just a belated brit milah.

At first, my mother was concerned about what looked like religious fanaticism, but when I stuck with the program, she not only accepted my decision but eventually returned to Judaism herself, after a fashion. My brothers also thought I had gotten carried away, but they, too, came to accept this new me (neither considered himself Jewish, but they had both been “out” for a while as having been born of Jewish parents). It’s been a long, slow road of religious growth since then, but eventually, I married a Jewish woman, had a son who got his brit milah on time, and am now shomer shabbat, part of a frum community in Sandy Springs, Georgia.

And the irony of the Day of Atonement being what I have come to think of as my “Jewish birthday” is not lost on me.

“Love your enemies,” Jesus says. “Do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you. To one who strikes you on the cheek, offer the other also …” (Mathew, 5:38). These are beautiful words, inspiring. But they’ve always seemed to me to ask too much.

It’s not that Judaism doesn’t promote forgiveness. But the “turn-the-other-cheek” kind of forgiveness is not so much a thing. Yes, we are told, “You shall not hate your brother in your heart,” but God goes on to say, “and You shall surely rebuke your fellow, but you shall not bear a sin on his account” (Leviticus 19:17). The next line then forbids taking vengeance or bearing a grudge. So, it’s complicated. We’re not supposed to return wrong with hate, but we’re also not supposed to tolerate wrongdoing. We’re certainly not told, “When your brother teases you about being fat, also remind him you talk like Elmer Fudd.”

In the upcoming Yom Kippur service, Jews will confess a whole host of sins to God, “for those of which we are aware” and “for those of which we are not aware,” all of which, we are told, God forgives. But, says Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya, “for transgressions between a person and another, Yom Kippur does not atone until he appeases the other person.” (Mishnah Yoma 8:9)

In Judaism, forgiveness is not unconditional. Certain requirements must be met by both those who ask forgiveness and those who grant it. The person who needs forgiveness must enact teshuva, repentance. He must realize his wrong, change his behavior, and ask forgiveness from the person he has wronged. And only then is it that, according to Maimonides, the sinned against should “forgive him with a complete heart and a willing spirit.” (Mishneh Torah, Teshuva 2)

It was the Jewish concept of atonement that came to my aid a few years ago, when I sought forgiveness from the same brother who, as a child, I couldn’t forgive.

He and I are on opposite sides of the political divide, and on the eve of the 2020 election, he wrote something in a chat with me and my oldest brother that really pissed me off, and I lashed out and wrote back some much nastier things that he had the good sense to delete before reading. Looking back, I realize my anger with him was partly a function of my love and respect, which is to say that his holding strong opinions diametrically opposite to mine was especially galling given that I wanted his approval. Regardless, I was in high dudgeon, on the verge of severing ties altogether—until the High Holidays approached, and a friend said to me, “Are you going to go into Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur with all this anger in your heart against your brother?” And that’s when I realized I had wronged him and had to ask his forgiveness, which I did, and which he graciously granted. We still can’t discuss politics together, but we’re friends again.

Might we have made it up without Yom Kippur? Maybe. But the annual reminder to seek forgiveness certainly helped heal a wound that otherwise might have festered. So, yes, as a child I didn’t go whole-hog Christian because I couldn’t forgive my brother. But maybe if I had, I would never have come back to Judaism later in life. I like to think that God saved me from being saved so that, among other things, decades later, I could ask my brother’s forgiveness as a Jew.

Thomas P. Balazs is an essayist, fiction writer, and perplexed Jew living in Atlanta.