A Wintry Tisha B’Av

In the Southern Hemisphere, feeling out of sync on a day of communal mourning

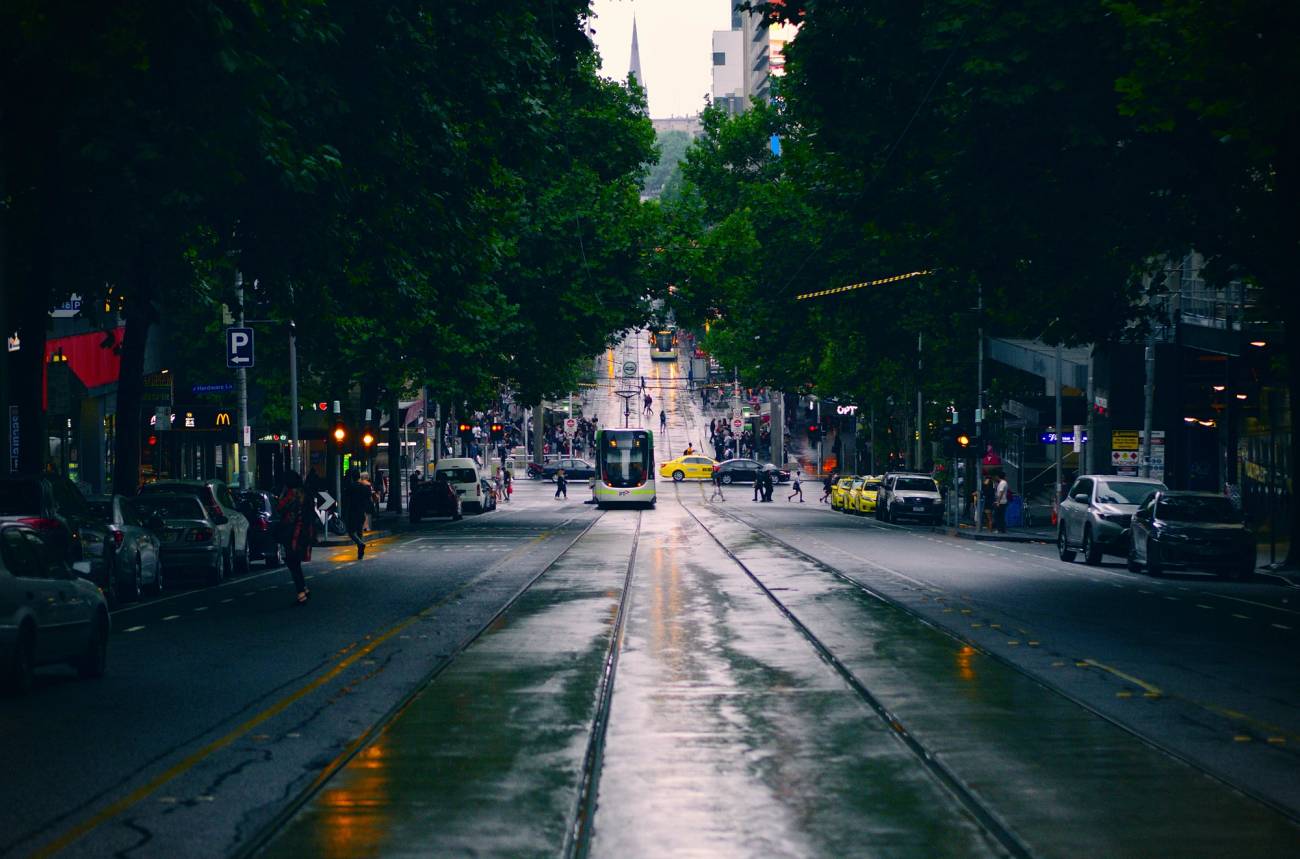

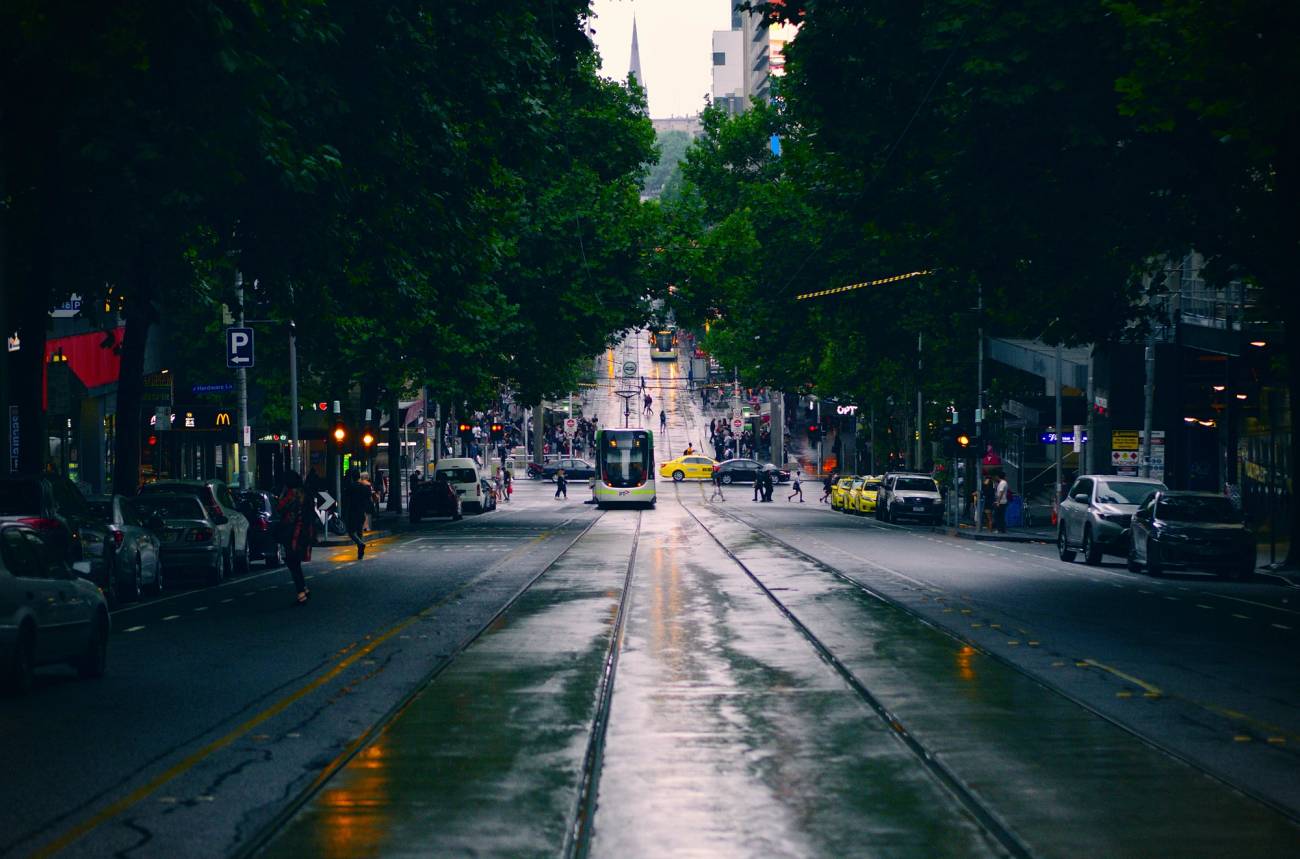

Leah Groner, a dual Australian American, remembers the first time she experienced Tisha B’Av in the Northern Hemisphere, around 11 years ago. Growing up in Melbourne, Australia, she was used to fasting on Tisha B’Av in the winter, when the weather is often cold, and the fast usually begins around 6 p.m. and ends around 7 p.m.

“I was at my aunt’s house in New York. Everyone was making a big deal about drinking Gatorade and Powerade, those drinks with electrolytes. I remember saying, what is the big deal? It’s just Tisha B’Av,” she said. “And my cousins were like: No, you don’t get it, it’s the summer, it’s hot, it’s long. You really need to prepare. Aside from just eating, I saw the serious [hydration] preparation that was going down. That is when I realized that we had Tisha B’Av very easy in Australia.”

Around the world, Tisha B’Av, the saddest day in the Jewish calendar, is marked by the reading of Lamentations in the scroll of Eicha, and a 25-hour fast where both food and drink are prohibited. Commemorating a litany of tragic events that befell the Jewish people, including the destructions of both the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem, it is a solemn day. In the Northern Hemisphere, Tisha B’Av is marked when many children are at camp, during the peak of summertime, compounding the difficulty of the fast, where heat can cause dizziness, fainting, and for those who are pregnant, even premature labor.

However, in the Southern Hemisphere, where Tisha B’Av is marked during the winter, in the middle of the school year, there is an additional challenge emphasizing the sadness of the day, when the seasons are out of sync: During Tisha B’Av, Southern Hemisphere Jews can feel a sense of distance and disconnect from their fellow Jews during what is meant to be a communal day of mourning.

Pato Binyamin, a Uruguayan Israeli remembers spending Tisha B’Av at his synagogue in Montevideo. “In Uruguay, on Tisha B’Av it’s good weather for a fast, but it’s not nice weather. Its winter, its rainy, its cold,” he recalled. “In the evening, we read Megillah, and kinot, and we will often take a text of some massacre like in Hebron in 1929 or something from the Holocaust and read it in Spanish to help people feel closer to the tragedy.”

Binyamin remembers that while he lived in Uruguay, prior to making aliyah, the day would evoke a sense of longing. “Tisha B’Av is one of those days where you feel how far you are from Israel. In Uruguay it is the opposite season, and it is more than a 20-hour flight to Israel. On Yom Ha’atzmaut I do not think you feel like that—I think you feel connected and happy for Israel,” he said. “But on Tisha B’Av, you realize how far you are from Israel because Tisha B’Av really symbolizes the beginning of the exile.”

To increase connection to the sadness of the day, some Jewish communities in the Southern Hemisphere try to enhance their local Tisha B’Av experience by bringing in local examples of tragedies.

“In South Africa, my shul is very traditional,” said Lior Blumenthal, a native of Johannesburg. “During Eicha, we sit on the floor, the lights are dimmed. It is a very somber and morose atmosphere.”

One year, she remembers, her synagogue brought a survivor of the Rwandan genocide to speak to the congregation about the genocide. “In Rwanda, they went through a massive genocide in 1994. The Hutus were killing the Tutsi people. In 100 days, 800,000 people died brutal deaths,” Blumenthal recalled. “I remember as a teenager a survivor came to speak to us on Tisha B’Av and that was very meaningful.”

It’s not just Tisha B’Av that is out of sync. In the Southern Hemisphere, communities grapple with the question of how to celebrate and mark Jewish festivals that are often linked to agricultural events and seasons that are in reverse. “It is hard. In Australia, there are agricultural parts of the holiday that just do not ever fit,” reflected Leah Groner. “Growing up I never realized we are out of sync. So, it’s a challenge to make the chagim meaningful when we live so far.”

Despite the challenges, this unique set of circumstances is not without some occasional benefits.

“Tisha B’Av falls in the depths of winter, the shortest, darkest, and most miserable days of the year,” said Gaby Lefkovitz, an Australian who has spent time celebrating the Jewish festivals in both the Southern and Northern Hemispheres. “And then you emerge out of the three weeks to a new season, to spring, to renewal, ready for a new year with Rosh Hashanah and Sukkot. In the Southern Hemisphere, you can tap into the underlying themes of the chagim—the solemnity of Tisha B’Av in winter, embracing nature on Sukkot as spring sets in, gathering for a cozy family meal together on Passover as summer winds down. Admittedly using this logic, though, Hanukkah makes no sense in the summer!”

Ari Rubin, an Australian American rabbi who runs a Chabad Center in the far north of Australia, faces an extra challenge. Living in Cairns, a tropical tourist destination, he experiences all Jewish festivals in a place that only has two seasons: wet and dry.

He remembers the intensity of spending Tisha B’Av in the Northern Hemisphere one year.

“I was in the Jewish ghetto in Venice. The whole community comes together in one of the shuls. It was an old, ancient synagogue with oil lamps. Everyone was given these thin candles. The cantor was chanting the haunting tune of Eicha and kinot,” he said. “It was very powerful, we were reminded of the persecution that happened in the past and I really felt connected to the persecution of Jewish people that is commemorated on Tisha B’Av.”

He contrasts this experience with his current location, a popular beach and holiday spot in Australia: “Here in Cairns, Tisha B’Av falls during peak season. It is literally in the middle of when we get all the international tourists and Australian tourists,” he said. “In Cairns it’s incredible weather and the rest of Australia is cold. And in America it is summer break. In Cairns at this time, it’s like paradise. Every day it’s perfect weather.”

Despite the geographical challenges, Rubin still tries to convey a sense of the seriousness of the day to his congregation, by focusing on the greater meaning of Tisha B’Av, and the Jewish understanding of time and seasons, despite his idyllic location.

“When you focus on the Jewish center according to Halacha, the Jewish time zone is not the same as the Greenwich Mean Time zone. In Judaism, Israel is our Greenwich. However, living out of sync, we focus on Israel as the center of our lives,” he said. “This adjusts us to be able to appreciate the centrality of Israel to the world and the centrality of Jewish culture to our lives.”

Nomi Kaltmann is Tablet magazine’s Australian correspondent. Follow her on Twitter @NomiKal.