The Year We Hung Hitler

A 1946 Purim celebration in the Landsberg DP camp

Purim wasn’t simple after the war, and it was even less simple during it. In his book on the diaries from the ghettos and camps, David Patterson comments on the complex place that Purim occupied in the war years:

The diarist was faced with a staggering disjuncture between the festive occasion and the days of destruction. While the disjuncture lay in the fact that in this instance, it seemed, the Jews would not be delivered from destruction, very often it was handled by suggesting a similarity between Haman and Hitler.

He includes this touching comment from Yitskhok Rudashevski, a young Jewish teenager who lived in the Vilna Ghetto, who wrote from the ghetto that:

We were in the mood for Purim, so let it be Purim. We were the ones who set the tone. We sang songs, presented a “Purim play” ... We laughed our fill and went to sleep. We are waiting for the real Purim. Next year we shall eat Hitler-tashn.

Rudashevski was killed in 1943. Patterson also includes this moving entry from the Kovno Ghetto:

Today is Purim. Hitler has promised that there will be no more Purim festivities for the Jews. I do not know whether his other predictions will come true, but this one is yet to be fulfilled ... none other than our little children, our Mosheles and Shlomeles, give the lie to Hitler’s prediction by celebrating Purim with all their innocence and enthusiasm …

And we cannot forget the chilling sermon of the rabbi of the Warsaw Ghetto, R. Kalonymos Kalmish Shapiro, known as the Aish Kodesh, who taught on Purim in the ghetto during the war years that just as Yom Kippur “purifies by its very essence,” without any necessary teshuva or proper headspace, so too we must accept that the “very essence of Purim causes joy,” no matter our circumstance. We cannot appreciate what context birthed this thought for this Hasidic teacher.

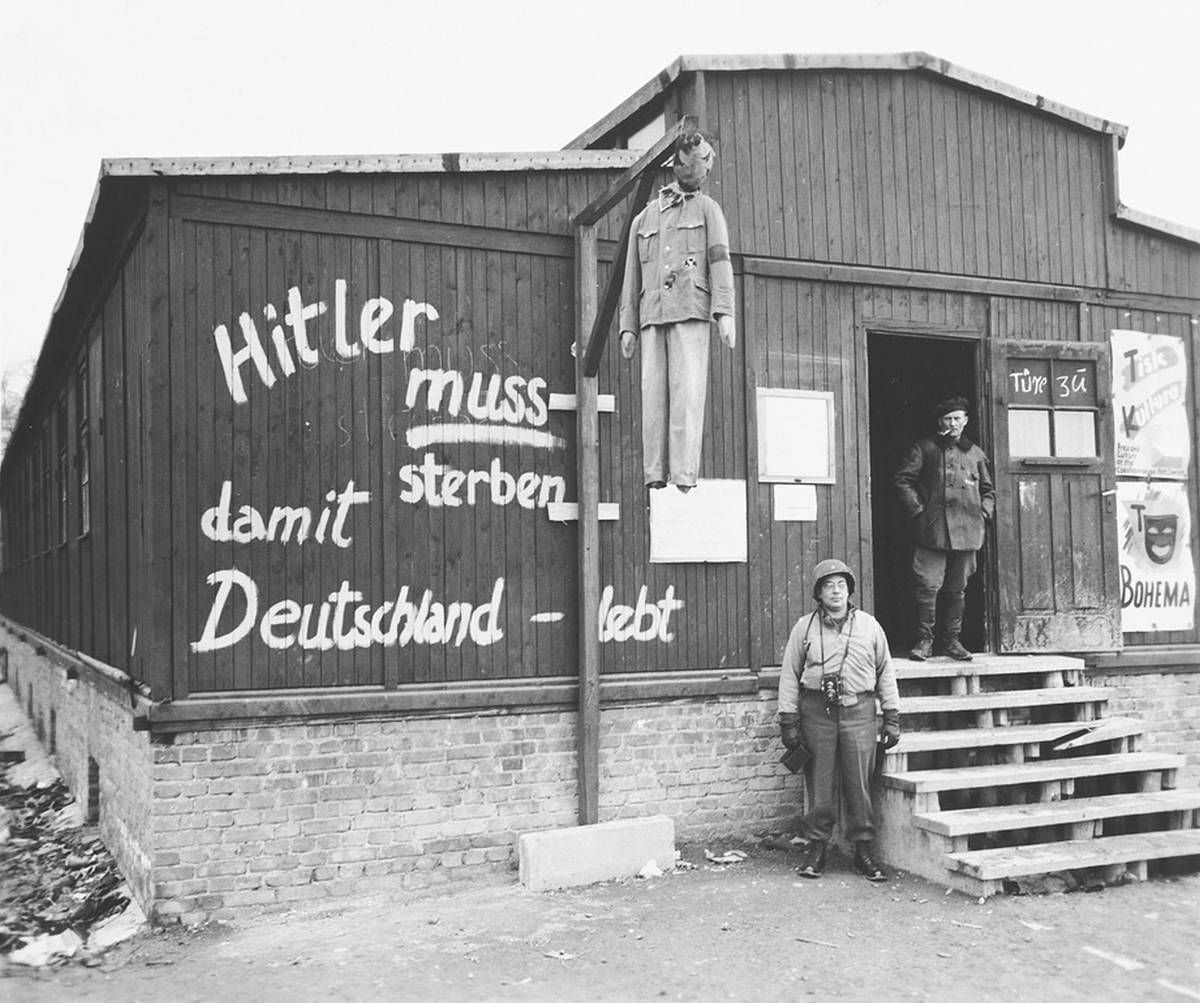

This makes the celebration of Purim after the war all the more intriguing. On Purim in 1946, Hitler was hanged—again and again and again. Hitler was hanged in Buchenwald, and likely other camps, but he was also hanged with particular zeal in the one DP camp: Landsberg. In 1946, the Landsberger Lager-Cajtung reported that “Hitler hangs in many variants and in many poses: a big Hitler, a fat Hitler, a small ‘Hitler,’ with medals, and without medals. Jews hung him by his head, by his feet, or by his belly.”

In Landsberg we are left with a particularly remarkable set of images for what this Purim looked like. Consider the stunning picture of four good-natured men presiding over the grave of Hitler. The tombstone reads: Here is buried the oppressors of the Jews, Haman ben Hamdata, Adolf Hitler … among the insects and hell shall they find rest, may their names be erased.”

And in Landsberg on Purim 1946, it all culminated with a public burning of Mein Kampf. The Lansberger Lager-Cajtung exuberantly reported:

At seven o’clock in the evening, at the sports field, there took place the public symbolic burning of Hitler’s Mein Kampf. The flames, which licked at the black night sky, carried far, far, over mountains and seas, this tiding: Am Yisrael Chai! Jews live on, will live! Hitler, may his name and memory be blotted out, has lost his “kampf,” his battle, and we Jews, although we have paid dearly, have won the battle. So Haman ended, so Hitler ended, so will end all the enemies of the Jews.

When I first saw these pictures, late one night while trawling through the archives of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum at my kitchen table, I was caught, but still from afar. And then I found out that Hitler had written Mein Kampf in Landsberg, while incarcerated there with Rudolf Hess in 1924. What happened in Landsberg on Purim in 1946?

The story of the Landsberg Purim is part of a broader story, of DP camps and survivors and the wreckage that exists after the end and before the beginning.

The conditions in the DP camps were negligible, as an article from December 1945 reports:

Conditions of overcrowding, under-nourishment and lack of heat at the Landsberg camp for displaced persons, brought to public attention two weeks ago with the temporary resignation of Dr. Leo Srole, camp welfare director, have been ameliorated, according to a report received today from A.C. Glassgold, camp director.

While denying that conditions at their worst could be compared with those of former Nazi slave labor camps, Glassgold did affirm that improvements are being made.

Stuck in the same places of their earlier confinement, with nowhere to go, the survivors languished. Going home wasn’t simple, with stories of postwar pogroms in the ether. Entry to Palestine was still blocked by the British, and quotas enforced by most Western countries left the refugees stateless and destinationless, waiting.

Work itself, and the notion of “productivity,” was complicated for these DPs. Glassgold notes that some “saw the need to distinguish between imposed and elected work … maintaining … that all work should be done by the residents … themselves.” Others were less willing to dive into elected work, and along with those that were physically incapable of physical work. Dr. Leo Srole remembers:

It was a time when things were very bleak. The British were hounding the ships to Palestine. It was winter, a terrible winter, and the mood in the camp was very low.

As December 1945 turned into 1946, Srole met with Boris Blum, a survivor who held the position of director of food in Landsberg. The holiday of Purim was approaching, and Blum suggested a Purim carnival in addition to the usual Megillah reading and performances. Blum told his daughter: “Srole was interested in linking … a Purim celebrating Hitler’s defeat [with] a week of work … there was the idea that work should again become the impetus of reentering life, because many people were depressed after the liberation.”

On March 15, 1946, the carnival was announced in the Landsberger Lager-Cajtung:

The week of Sunday, March 17, until Sunday, March 24, is proclaimed the week of work in Landsberg! The week will begin Sunday, March 17, with a grand Workers’ Purim Carnival. All buildings in the center should be festively decorated for this day! All residents should decorate the outer windows of their rooms. The block managers should organize the decoration of their buildings. Prizes will be awarded for the most attractive building and for the most beautifully decorated window!

Although the regular Purim accompaniments happened, with a Megillah reading, feast, song, and the rest, the tone and character of this Purim speak for themselves. The Megillah was read by a survivor wearing the striped uniform of the camp, there was a motorcycle procession, an abundance of posters depicting Hitler and other high-profile Nazis in various compromised positions, and then there were the hanging Hitlers, the burning Mein Kampfs, and Hitler’s grave. Best of all, perhaps, is the man dressed up as Hitler. This image may the most striking yet to our eyes.

The best article we have on the Landsberg Purim is from Toby Blum-Dobkin, Boris Blum’s daughter, in “The Lansberg Carnival: Purim in a Displaced Persons Center,” from an obscure, impossible-to-find book, Purim: The Face and the Mask: Essays and Catalogue of an Exhibition at the Yeshiva University Museum February-June 1979. Blum-Dobkin’s article is invaluable, and offers a direct window into what this Purim meant for those who lived through it, and through that which came before. Blum-Dobkin writes:

Although imitation may be at times a form of flattery, it can also be a powerful weapon and a strong form of ridicule. By assuming the persona of Hitler, a liberated Jew can illustrate his complete power over his former opposer. The masquerader dictates and controls the actions of the character he is playing; in performing the exaggerated Nazi salute, the Jew can mock the Nazi and emphasize the transfer of power. When the liberated Jew donned the striped suit of the concentration camp, this dramatized the change of status that had taken place. He wore the striped uniform not as a slave, but as a free person, not in the Nazi death factories, but upon a speaker’s platform. Those wearing the uniform memorialized those who had died and at the same time emphasized the reversals that had come about.

What makes these pictures so singularly powerful?

Elliot Horowitz, in Reckless Rites, notes that the vengeance narrative on Purim allows the oppressed Jews to feel as if they had practiced vengeance on their hated enemies, while only acting out a benign fantasy. He utilizes James Scott’s language of the “dialectic of disguise and surveillance that pervades relations between the weak and the strong,” which manifests in a “hegemonic public conduct” as well as a “backstage discourse consisting of what cannot be spoken in the face of power.” This is true.

In a different key, the poet Dale Biron writes in his “Laughter”:

When the

face we wear

grows old and weather, torn

open by time,

colors,

tinted as dawn

like the late

winter mountains

of Sedona

ashen and crimson,

it will no longer

be possible

to distinguish

our deepest scars

from the long

sweet lines left

by laughter.

This feels to me like the kind of homogenizing poets convince themselves of, that laughter and pain and joy and hurt all flatten us equally, that all leave us more beautiful. I’d like to believe these words, but they don’t convince me. Blake warned us of this: “It is an easy thing to laugh at wrathful elements …” when the wrathful elements don’t affect us. Blake was talking about the empty joy we might feel for “the thunder storm that destroys our enemies’ house,” but I think his warning rings true here.

I can’t say why, but I know that it is this synapse between the lines left by our deepest scars and those left by laughter that makes these pictures meaningful to me. Or perhaps it’s just the simple radicalism of people finding a way to laugh, in the grim reality of 1946, that will always pull a smile out of me, no matter what happens in our own world devoid of meaningful laughter. But Rumi comes to mind, and they seem perfect words to end with, no matter how relevant they might or might not be: “What is the body? Endurance. What is love? Gratitude. What is hidden in our chests? Laughter. What else? Compassion.”

Yehuda Fogel is a writer and editor at 18Forty, a Jewish media company, and was formerly an editor at the Lehrhaus, an online forum for Jewish thought and ideas.