Unholy Warrior

The death of Osama Bin Laden is a major achievement for the Obama Administration, but it underscores the difficulty of waging a successful cultural war in the Middle East

The killing of Osama Bin Laden by a U.S. special forces team operating deep inside Pakistan is a historic event that marks the end of the way that most Americans have been told to think about terrorism since Sept. 11, 2001, and likely ensures President Barack Obama’s re-election in 2012. What Obama will do with his new-found political power between now and then is unclear. But the nature of the problems he will continue to face has been thrown into sharp relief by the place where Bin Laden was finally cornered—not in a cave, or in a mud-walled village in the lawless tribal areas on the Afghan border, but in the protection of what appears to be a custom-built compound in the Pakistani army garrison town of Abbottabad, just 35 miles north of Islamabad.

The hunt for Bin Laden was one of the most difficult campaigns ever undertaken by American policymakers, insofar as the failure to kill or capture a single man signaled failure in a much larger war—even if that war was going well. It was also one of the misleadingly easiest campaigns insofar as it promised that the death of one man represented a victory.

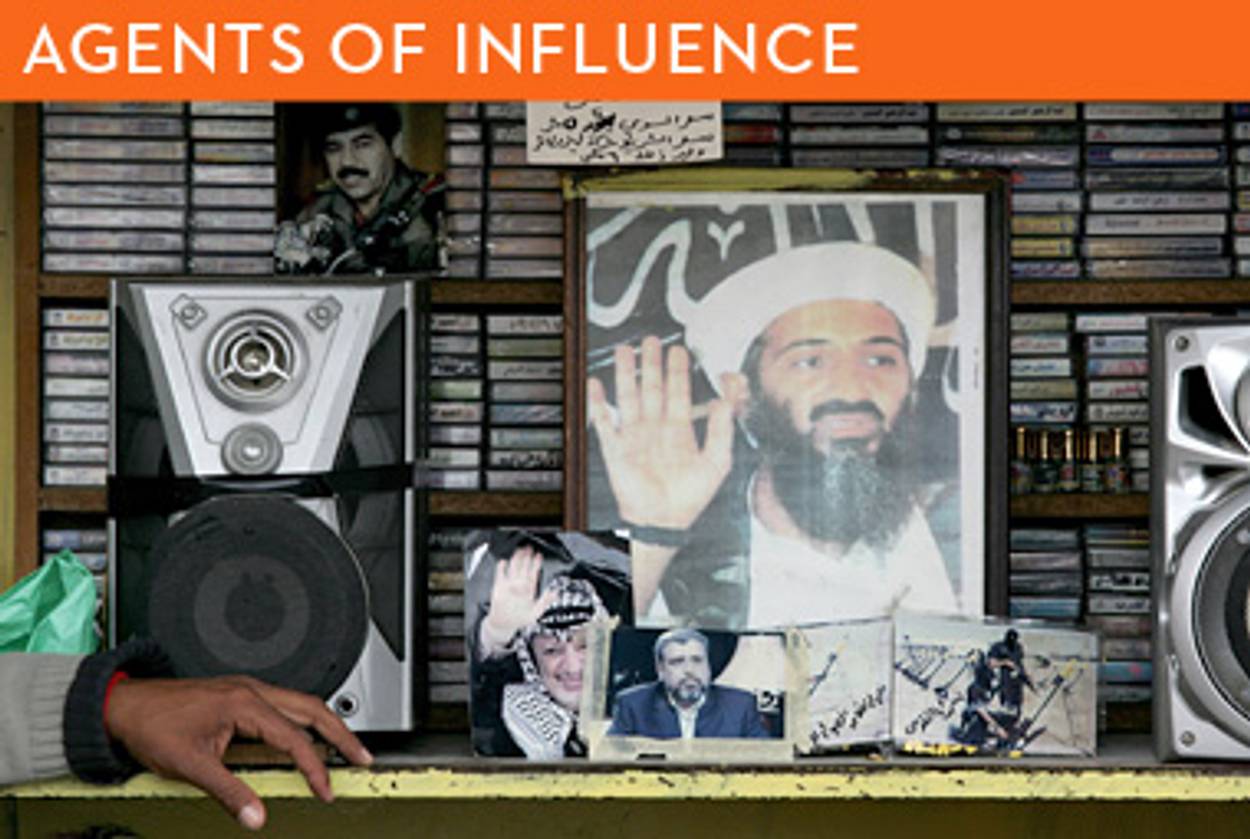

The assassination of Bin Laden is a major achievement for the Obama Administration, the intelligence community, and the armed forces, but there is also no mistaking that finally all it amounts to is a parade celebrating a victory in the last war, the war that ended 10 years ago with the collapse of the World Trade Center towers. Al-Qaida seemed to be at its height, but looking back it is clear that by this moment it was breathing its last significant gasp. There were to be no more spectacular attacks, and Bin Laden’s field officers were hunted by the United States and its allies around the world. The group’s influence extended as far as inspiring disaffected young men to strap bombs on themselves—a tragedy for their victims, from Madrid to London and Baghdad to Kabul, but al-Qaida’s geostrategic weight was nothing in comparison to Hezbollah and Hamas.

Most important, we’ve known now for a decade that the real problem isn’t shadowy networks of rogue operators, or superteams of comic-book villains like Bin Laden and associates, but the Arab and Muslim states that sponsor terror, like Iran, Syria, Saudi Arabia, and of course Pakistan, whose army and intelligence service appears to have actively protected Bin Laden for much of the past 10 years while receiving tens of billions of dollars in American aid.

It doesn’t take much acquaintance with the language of international politics to read between the lines of Obama’s announcement last night and understand that Bin Laden’s capture happened with the active cooperation of the Pakistani government—after elements of Pakistan’s military and security services that had been hiding Bin Laden either lost out to another clique who saw an upside in handing him over to the Americans, or were themselves persuaded to sell him out. As Obama explained on Sunday night, he was first approached with the intelligence about Bin Laden’s whereabouts in August. The location of Bin Laden’s custom-built compound in a Pakistani army town tells us who those sources probably were—the same people who have been protecting Bin Laden for the past 10 years.

Why now? Perhaps the Pakistani army saw how easily the United States got rid of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak and got scared of losing U.S. support. Perhaps the Saudis, who have been a major source of financial support both for Pakistan and for Bin Laden, got tired of al-Qaida’s role in undermining the government of Yemen, which is Saudi Arabia’s next-door neighbor, giving a further opening to Iran to spread its influence in the Gulf.

***

But still: Why did the operation to capture one man last more than 8 months? Because one of Washington’s key allies in the Muslim world was negotiating with the Obama Administration and didn’t cut the deal until it was happy with the price. Once they were happy, it was possible for two U.S. helicopters to fly through Pakistan’s sophisticated air defense system, built for an all-out war with India, to get their man.

Just as Bin Laden’s refuge in Pakistan is unimaginable without the long-term cooperation of the country’s leading officials, the entire enterprise of transnational terrorism is inconceivable without the logistical, financial, and often military support of states, which the United States has long tolerated while using its knowledge for its own diplomatic ends. Syria, for instance, has been listed on the State Department’s state sponsors of terrorism list since the register’s inception in 1979, but up until George W. Bush, no one wanted to make too big a deal of it. George H.W. Bush needed Damascus’ support to take on Saddam Hussein in Operation Desert Storm and go to Madrid for peace talks with Israel. The peace process was key for the Clinton Administration as well, which is why it, too, didn’t make too much of Syrian terror. Washington policymakers never took anti-American terror lightly, but they believed that at times there were more significant strategic interests; a state’s support of terrorism was something that Washington could use as leverage.

After Sept. 11, Washington came to see those same state sponsors of terrorism in sharper relief. Washington no longer considered regional regimes as its primary interlocutors, but rather instead as the source—through the neglect of their people, or through active state sponsorship—of America’s biggest immediate national security problem. By pushing its Freedom Agenda, the Bush Administration chose to go over the heads of Arab and Muslim rulers and speak directly to the masses—and for all their differences in style and tone, Bush’s successor sees the problem roughly the same way.

The entire point of Obama’s Cairo speech was to address the “Muslim world” even as he undermined a longstanding U.S. ally in his own capital—a dynamic that achieved one of its desired ends when Mubarak stepped down from office in February.

So, while Obama is believed by many in pro-Israel circles to have a special animus against the Jewish state, the truth is that his positions on Israel are part of a larger philosophical and strategic approach to the region that seeks to position the United States as a champion of the Muslim masses against the regimes. Arab-Israel peace is how the United States proves its bona fides. If Obama squeezes Jerusalem more than have other U.S. policymakers of the recent past, that’s because Israel is a strong country and a U.S. ally in good standing that can withstand the pressure—especially, in Obama’s view, since American success in winning Muslim hearts and minds will benefit Israel in the long run.

As far as the real American war on terror goes—the war that we have been waging under two presidents since Sept. 11, 2001—finding Bin Laden was never the issue. The question is what ideas do you use to wage a successful cultural war in the Middle East?

Essentially there are two different tactics. The first is to inject our own ideas of democracy, women’s rights, and minority rights into Arab politics, the downside being that such ideas will only appeal to a minority of people in the region. It’s hard work winning a cultural war if you keep telling the people you’re trying to convince that their values are wrong. If Bush believed that the only remedy for the failures of Middle Eastern political culture was democracy, his fault was in failing to see that sick political cultures are not immediately susceptible to remedy. The other approach is to temper some of your own values, to make room for the ideas of your interlocutors.

Obama appears to believe, not incorrectly, that his predecessor was too dogmatic, and that sometimes you can get more done by listening than speaking. His problem is that the more he is willing to bend on American values, the more he is going to be tilting toward the political culture that gave us the figure whose death we’re now celebrating. Bin Laden’s death, which was celebrated by Americans in Times Square, Detroit, and baseball parks, was publicly mourned by the leadership of Hamas in Gaza, with the elected Palestinian Prime Minister, Ismail Haniyeh, referring to the dead al-Qaida chief responsible for the murder of more than 3,000 Americans as a martyr. “We condemn the assassination and the killing of an Arab holy warrior,” Haniyeh told reporters. “We regard this as a continuation of the American policy based on oppression and the shedding of Muslim and Arab blood.” If dialogue has limits, then this should be it. And if it isn’t, it is unclear what we are fighting for.

Lee Smith is the author of The Consequences of Syria.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).