July 4th marks the 40th anniversary of the famed rescue at Entebbe, in which Israeli commandos flew 2,000 miles into the heart of Africa to bring home over 100 Jewish hostages whose Air France flight had been hijacked to Uganda by Palestinian and German terrorists, abetted by Ugandan strongman Idi Amin.

The rescue operation—subsequently renamed Operation Yonatan for its commander Yonatan Netanyahu who was killed during the rescue—captured the imagination of military theorists, filmmakers, and ordinary people, and continues to spark spates of retelling and analysis at every significant anniversary. Just last year, a new exhibit of previously unseen relics of the raid opened at the Rabin Center in Israel. But despite all the movies, books, and exhibits, there are many lesser-known details and subplots of the rescue that still retain the capacity to surprise. Here are some:

How many Israeli Prime Ministers or future Prime Ministers played a role in the rescue at Entebbe?

It is widely suggested that Binyamin Netanyahu’s political career was born, or at least boosted, by the legendary status of his brother’s sacrifice. What is less known is that Bibi was also a member of Sayeret Matkal, or “the Unit,” which performed the raid. He did not actively take part in the raid, in keeping with the policy that two brothers not be risked in a single operation. Yitzhak Rabin was the serving Prime Minister who had to sign off on the rescue. He was very reluctant, but ultimately agreed with his Defense Minister, future Prime Minister Shimon Peres, to exercise the military option. Finally, Ehud Barak, yet another future PM, was dispatched to Kenya, where he made the arrangements for refueling the Hercules aircraft on the way home.

What tipped the balance in favor of the military option?

Any way you slice it, committing to such a plan was going to take a leap of faith. Iddo Netanyahu (Entebbe: A Defining Moment in the War on Terrorism, Balfour Books, 2003) describes a decisive moment as the personal assurance given by Yoni to Shimon Peres on Friday of the fateful week: “’My impression was one of exactitude and imagination,’ Peres says, adding that Yoni’s complete self-confidence had a strong influence on him.” Peres’s forty-five minute meeting with Yoni fortified his belief in a military option, which he recommended to the Prime Minister.

Which hostage has a connection to an Israeli military hero almost forty years later?

Ninette Morenu was released by the Entebbe hijackers on June 29, 1976, thanks to her non-Jewish sounding name. Her keen powers of observation enabled her to help authorities construct a detailed diagram of the layout of the terminal. The diagram, which is part of the Rabin Center exhibit, helped the planners of the raid settle crucial doubts. Thirty years later, in the Second Lebanon War, Emmanuel Morenu, Ninette’s grandson and a member of Sayeret Matkal—the unit that rescued his grandmother—fell in battle. The Times of Israel quoted a Mossad source describing the grandson as “one of the best officers in the history of Sayeret Matkal.”

Which hostage was a frustrated Nazi-hunter?

In his 2015 book, Operation Thunderbolt, military historian Saul David paints a picture of Michel Cojol, a French management consultant, who helped as an interpreter during the Entebbe crisis. He had previously determined to personally execute Klaus Barbie, the Gestapo chief he considered responsible for his parents’ deaths, along with so many others. He purchased a gun and tracked the Nazi down, but could not pull the trigger, as he recalled the words of Elie Wiesel, “Every murder is a suicide.”

Which Entebbe hostage was present at two other moments that made history?

Haaretz records that Akiva Laxer, a 30-year-old lawyer at the time, had previously been at Lod Airport during the terrorist massacre in May of 1972, and then had been present at the Munich Olympics a few months later, when terrorists abducted and murdered Israeli athletes. Before traveling this summer, you may want to check the flight manifest for his name, just to be sure…

What was the last thing Yoni wrote and why did he write it on an air-sickness bag?

The flight to Sharm el-Sheikh (from where the raid was launched) was so bumpy that the soldiers were constantly sick and the floor was coated in vomit. One soldier from the raiding party was so weak upon arrival that he had to stay behind and was replaced by Amos Goren, who was originally assigned to a different plane. Yoni brought Amos up to speed on the plan by sketching the terminal on the back of an air-sickness bag. That bag is now part of the exhibit at the Rabin Center.

How was Dora Bloch’s death the result of an attempt to to save her life?

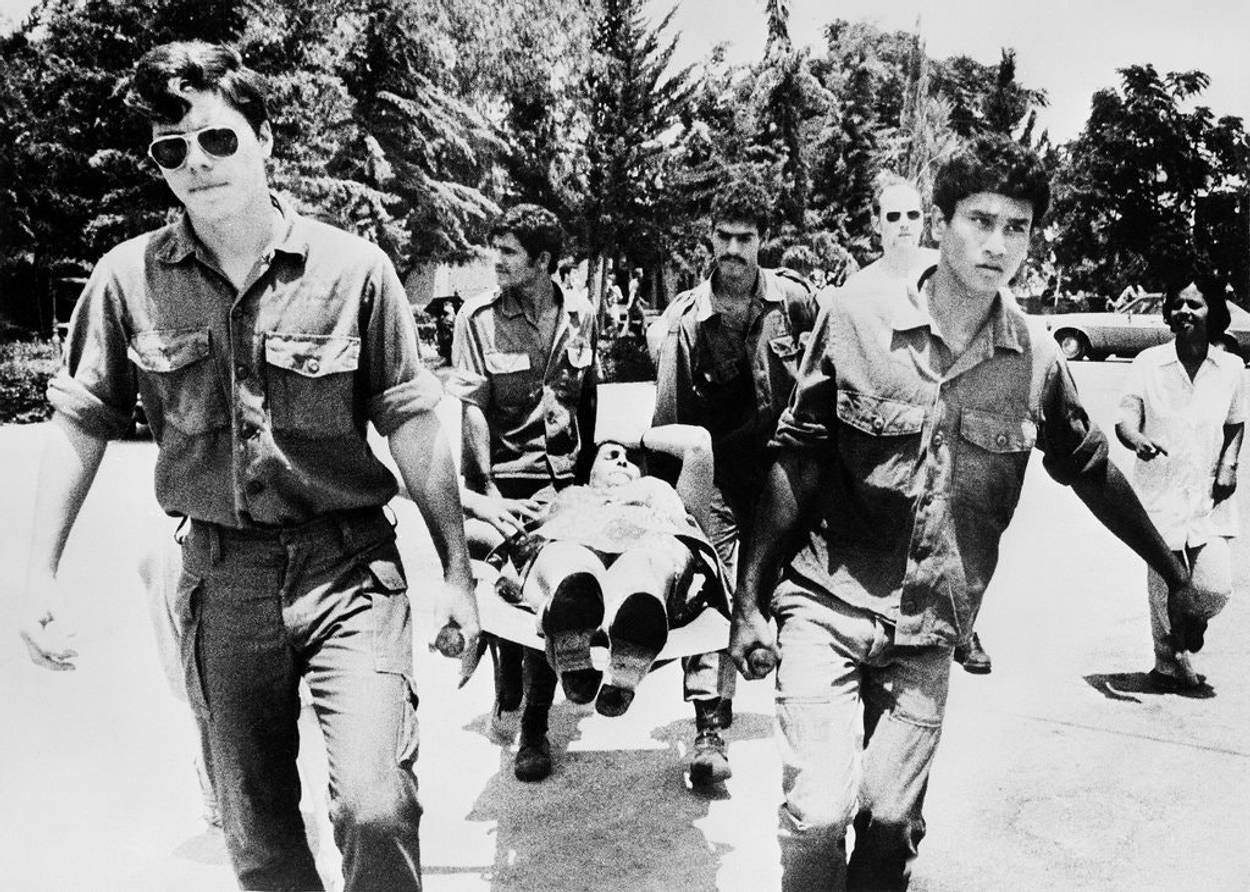

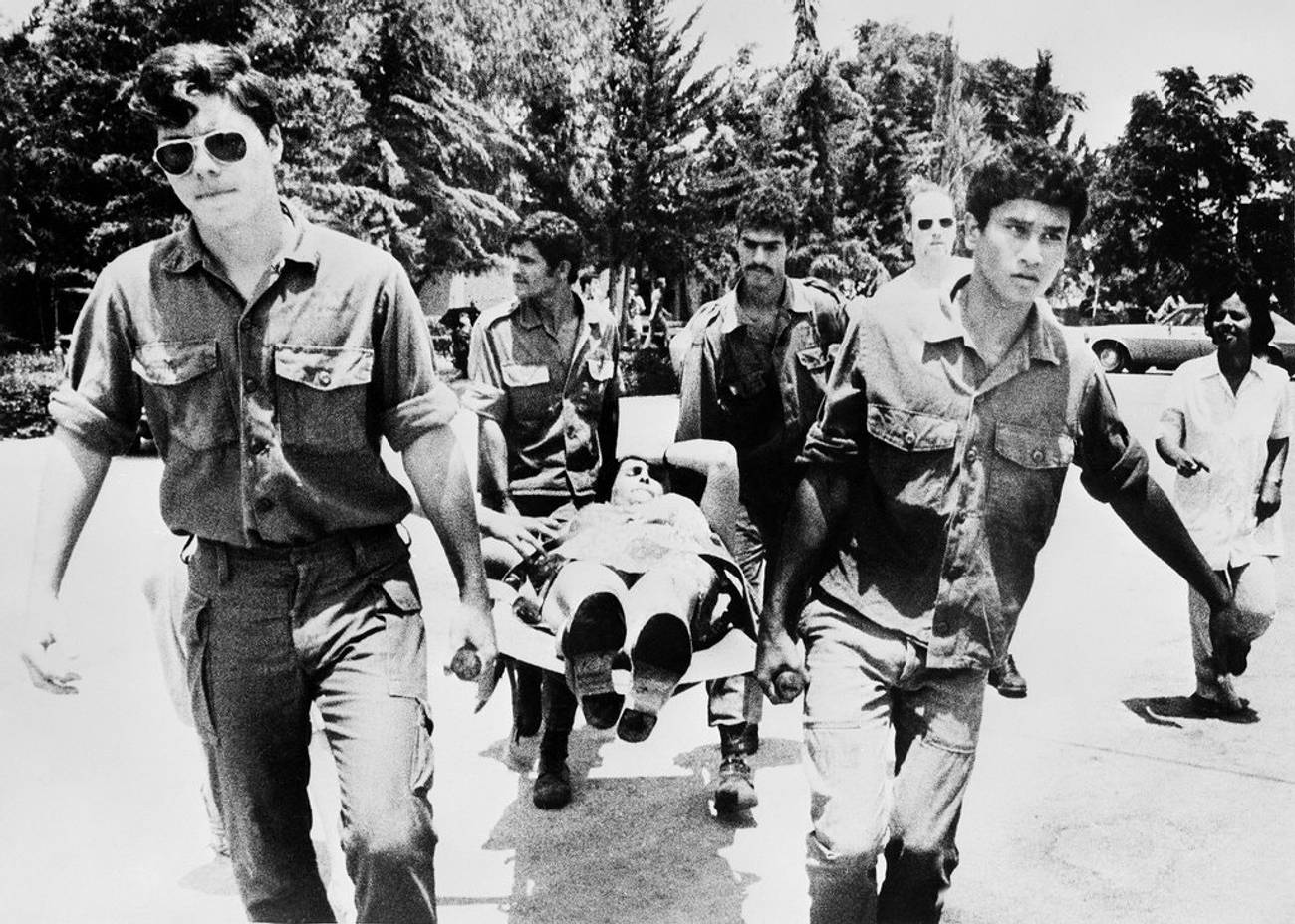

In fact, four hostages did not survive the rescue attempt. Jean-Jacques Mimouni was killed when he jumped up during the rescue and was shot by a rescuing soldier. Pasco Cohen was shot in the pelvis by Israeli fire and died on the operating table in Nairobi. Ida Boruchovich was shot dead during the rescue but it is less clear whose bullet—Israeli or Arab—took her life.

The best known casualty was Dora Bloch, who began to choke on what has been variously described as a piece of meat or a chicken bone on Friday, July 2. She was taken to the hospital in Kampala for treatment. Saul Rubin documents how Idi Amin called Health Minister Henry Kyemba on Saturday to see how Mrs. Bloch was doing, with an eye towards returning her to the others. Kyemba, hoping to spare her what was looking more and more like a bitter fate with her countrymen, lied, saying that she needed another day for her recovery. By the time that day had elapsed, the rescue had taken place without her. In retribution, Idi Amin had her taken from her bed and shot.

Who was Surin Hershko and what unsung part of the rescue does he play to this day?

Hershko was tasked with checking other rooms in the terminal for hijackers and Ugandan soldiers. He suddenly encountered two soldiers on a staircase. One shot him twice and a bullet struck him in the neck, severing his spinal cord and rendering him a quadriplegic. In 2001, the twenty-fifth anniversary of the raid, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon awarded him a special medal.

How did the rescue of the hostages come perilously close to being a bloodbath instead?

While driving from the new terminal to the old one, where the hostages were being kept, the famous Mercedes carrying the soldiers—meant to resemble Idi Amin’s motorcade—was challenged by two sentries. Muki (Moshe) Betzer, Yoni’s deputy, tried to dissuade Yoni from firing on them, later writing that his previous experience in Uganda taught him that the challenge was a routine exercise and not a real threat. Yoni and another soldier in the car fired at one sentry with silenced revolvers. According to Iddo Netanyahu’s account, this exact scenario had been anticipated and the decision had all along been not to leave a soldier alive in their rear. The silenced shots, however, did not down the sentry. Further unsilenced shots came from the Israeli land rovers that followed in the Mercedes’s wake. These finally killed the sentries but at the risk of losing the element of surprise. It turned out that the terrorists were not alerted; apparently they thought that the Ugandan soldiers were shooting at each other.

How did Yonatan Netanyahu really die?

Depends upon whom you ask.

Israeli readers, unlike their American counterparts, are used to seeing flare-ups of a running dispute between the Netanyahu family and the mission’s second-in-command Muki Betzer regarding key issues in the account of the rescue. Muki’s written record is a chapter in his autobiographical Secret Soldier. He has also been interviewed extensively over the years. He contends that Yoni’s error in firing on the sentries threw off the timing and location of the disembarking and raid. Subsequently, while standing outside of the action, Yoni was shot by a Ugandan sniper firing from the imposing control tower.

However, the third Netanyahu brother, Dr. Iddo Netanyahu, has written three books to advance an alternative narrative. He interviewed numerous soldiers and made his goal the discrediting of Betzer’s account. The Netanyahu account maintains that the sentry scenario was foreseen and planned for. The raid was proceeding as anticipated but Muki hesitated on his way to the terminal. Yoni had to personally run forward, rallying the troops, and was shot, not from the control tower by a Ugandan, but from within the terminal by a terrorist. Official military accounts have generally retold the version of Betzer, as have most newspaper accounts. The Netanyahus argue that the soldiers were never properly debriefed, a task Iddo sought to remedy. A new book, Operation Yonatan in the First Person, based upon the recollections of soldiers, is very sympathetic to the Netanyahu family position. It formed the basis for a series of articles that appeared in Ynet over the last week.