Exit Ghosts

After a lifetime of idolizing Philip Roth, I discovered a better role model much closer to home

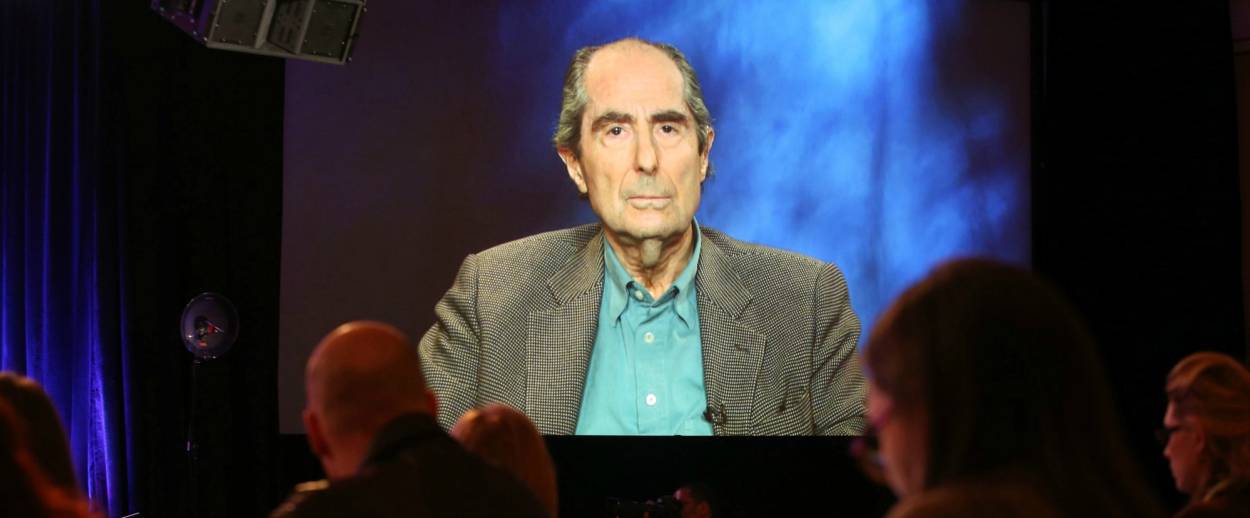

In junior high, I fell for Portnoy. As a neurotic middle-class teen who’d visited Israel (like his character), I over-identified with Philip Roth’s hysterically funny 1969 autobiographical anti-hero. I hoped to flee my repressed Midwest meshugenah clan, masturbate freely, confess my sexual frustration to the Freudian analyst I didn’t yet have who’d respond, “Now vee may perhaps to begin.” Reading the provocative, sacrilegious Portnoy’s Complaint was like escaping from suburban prison. If my staid doctor dad was my superego and oppressor, my favorite novelist was my id and inspiration. I wanted to be the female Roth.

This past year, six months into grieving the loss of my cantankerous father, my literary paternal figure Roth died of heart failure at 85, too. Now a middle-aged author nowhere near as successful as my dad or my idol, I obsessed over the overlapping histories in their obituaries. I’d thought they were opposite, yet their similarities stunned me. Their deaths made me question my longtime assessment of the two brilliant male voices that shaped my life. Had I fallen for the wrong guy?

My dad, Jack Shapiro, was born in New York seven months before Roth, 45 minutes from the author’s New Jersey birthplace. After working at my grandfather’s Lower East Side window shade store, he went to nearby NYU. An avid reader and poet, he had bookish aspirations. But good at science, he chose Chicago Medical School instead. Roth, whose dad worked in insurance, switched majors too, from Rutgers pre-law to English student at the University of Chicago, an hour from where my dad also pursued the American dream. They both taught and served in the army. In a story I imagined Roth liking, Dad wiped out syphilis for the St. Louis Health Department by offering a free beer at bars in exchange for a penicillin shot.

Adored by doting Jewish mothers, Philip and Jack became tall, handsome, sarcastic, lucky second children who outlived their only siblings. One noted difference: My grandpa Harold was born in Poland and came to New York as a teen. Roth’s dad, Herman, was second-generation; his steady finances made his son’s artistic choice easier. Yet my father was more fortunate in love. Perhaps haunted by the venereal diseases he’d treated, my father remained faithful to my mother. “Who you marry changes everything,” he always said. In Roth’s fictional universes, that might be amended to “who you screw.”

Indeed, sex was where these golden boys appeared to diverge. Roth uproariously depicted his multiple affairs; my dad had only one. As a rebellious high schooler, he fell for my red-headed Jewish mother, Miriam, an orphan who worked as a secretary. They were both virgins. Crafting her love poems at NYU, he tried to change that. Mom, a good girl, insisted on the 1940s version of Beyoncé’s “put a ring on it.” Thus he made the practical decision to become a doctor for her, proposing with, “I just got into med school in Illinois, ya coming or not?” He completed his residency in Michigan, raising four kids and veering politically right though no less sardonic. He hated my feminism and Rothian psychobabble, left-wing politics, prose and verse starring him as a sexist central character. I hated that my mother gave up working to raise us. When Dad told me, “Go get me a cup of coffee,” I sniffed, “You already have one submissive female in this family.”

He disapproved of my MFA at NYU, his alma mater. “Ya gonna sell your poems on the sidewalk?” he goaded, pushing law or medicine. In Manhattan, I chronicled my insane heartbreaks like my role model, not marrying a fellow writer until I was 35. I cheered when Roth won honors from the National Book Critics Circle, where I was a member. Though we never met, in 2011 I heard him read from his moving memoir of his father’s death, Patrimony. It paralleled my dad and grandpa’s final days but Roth seemed so more emotional and articulate than anyone in my mishpucha. His Pulitzer-winning American Pastoral shattered me, as I feared my father, like The Swede, was disappointed by his disaster of a rebellious daughter, as he “learned the worst lesson life can teach—that it makes no sense.”

In several of his 34 books, Roth circled around his two bad marriages—the first to Margaret, a blond gentile divorced secretary from Michigan, the mother of two kids, whom he wed when he was 26. She died after their 1963 divorce. Of course an author’s fiction—or journalistic accounts of their life—aren’t reality. Yet after his second union, to British Jewish divorcée actress Claire Bloom, ended acrimoniously in 1995, she published a pedestrian tell-all revealing his cheating and nastiness to her daughter. I believed he’d actually been the jerk he’d oft portrayed himself as. Still, I was riveted by his work and insistence that writing every day ruled his life: “My goal would be to find a big fat subject that would occupy me to the end of my life, and when I finish it, I’ll die.” I quoted him on aging: “Old age isn’t a battle: old age is a massacre. … Looking through my phone book is like walking through a graveyard.”

After Roth’s death, critics argued his legacy was tainted by misogyny. Feminist authors accused him of having an infantile preoccupation with himself and his penis, showing little empathy for women. Rereading, still adoring his books, I didn’t disagree. But would I have cherished his pages even more if he’d kept the same wife or had children, like my dad? After all, my No. 1 favorite novel was The Great Gatsby, an idealistic (albeit doomed) romance at the center instead of a piece of liver. Did Fitzgerald’s 20-year complicated marriage until death (with a daughter who sounded like Daisy) inspire a truer masterpiece? I debated whether Roth would have nailed the Nobel and a larger legacy if he’d had a longer union or whether the wrong partners had fueled his dramas. When a younger male Jewish author questioned if offspring were the enemy of literature, with each kid representing a novel you wouldn’t publish, I was intrigued that “having it all” wasn’t just a female conundrum. I recalled my father gave up his artistic ambitions for my mother.

At 57, with a treasured husband, a dozen books published but no babies, I analyzed my own failures trying to balance Freud’s two life forces: love and work. When Dad trashed the autobiographical elements in my writing, I repeated my shrink’s advice to “lead the least secret life you can.” Dad countered, “Repression is the greatest gift of the human intellect.” My sexist WASP therapist annoyingly reminded me, “You couldn’t get your books published until you were 43, after you had a wonderful husband character in the middle.”

It was true, emulating my fantasy mentor hadn’t helped me. Many of his heroes were woman-bashers. But agents and editors rejected early manuscripts from my single, raging feminist stage as “too man-hating.” I knew my animosity towards the other sex wasn’t as well-rendered as Roth’s. With the creed “art is everything,” his most enduring relationship was with his work. Yet if being close to my husband made me a better person and improved my writing, it squashed my old Rothian suffering artist façade. Indeed, his last few novels seemed repetitious to me. As a reader, reviewer, and self-appointed disciple, his characters’ emotional immaturity and myopia ultimately felt like a disappointing artistic limitation.

I was among the few loathers of the ugly narrator Mickey in 1995’s Sabbath’s Theater, who banged everything in sight. I preferred Patrimony. As a memoirist, I assumed I’d merely related more to his nonfiction. But maybe I’d longed to read a Roth protagonist maturely loving someone else. The reality of devotion wasn’t dramatic. My dad’s life, filled with lasting love, was quiet. He became chief of medicine at his hospital and a grandfather of five. Because of my idealized connection to Roth, I felt bereft when he announced he was hanging up his pen around the same time my father quit his 50-year career at 80, due to heart problems. I felt double sucker punched. Dad became gentler and wiser with age, though more frail.

On his 85th birthday, he became a patient at his hospital. Surrounded by my mom, siblings and his grandkids, he told me he was proud of me and whispered, “Family is everything.” Sitting on his sickbed alone one day, he shared his regrets. He’d felt bad that it took him decades to earn a good living, making Mom move around to accommodate his jobs. He trashed the problematic state of medicine, insurance, and malpractice. His rags-to-riches story riveted me. I wanted to hear everything he’d sacrificed to get from being a poor street kid to acclaimed doctor who prided himself on putting his children through college and graduate school, creating educational trusts for his grandkids. I felt awed by his legacy, wishing I hadn’t disappointed him. Roth, too, sounded ambivalent about his profession when he told a debut novelist/waiter: “It’s an awful field. Just torture … I would say just stop now. You don’t want to do this to yourself.”

During my father’s Midwest funeral service, led by our eloquent Reform rabbi, I gave a eulogy filled with emails he’d sent me. When I’d asked advice about a hideous bunion, he’d replied, “Well, your toe ain’t going to Hollywood. Cure is worse than the disease.” After the surgery that caused him to retire he told me, “Your mother is keeping me alive. But she wants me to entertain her. Now I know how we lasted 63 years. The secret is a big, big house.” The missives revealed how Dad’s gruff exterior hid a hilarious, romantic soul. Despite all his renown, reading of Roth’s burial at Bard College with no Hebrew prayers, before his friends and relatives but no spouse or offspring, made me feel sad and empty.

I’d so long coveted Roth’s scholarly acclaim. But decades of therapy later, reading his quote, “When I work, I’m on call. I’m like a doctor and it’s an emergency room. And I’m the emergency,” I felt more fascinated with my father’s half a century in actual internal medicine, helping other people. I felt lucky that my inability to make a living with my writing led me to teach more than Roth had. For the last 25 years, teaching enhanced my humanity. I didn’t wish I’d won more book contracts and wouldn’t trade my husband of 22 years for any prizes. I mostly regretted not being able to have kids and give Dad more grandchildren.

I saw how easy it was to be taken in by the external sheen of the bad boy of Jewish letters. Yet I’d picked the wrong paragon. Surprisingly, I found myself wishing I’d been more like my father. All the complex, meaningful words that haunted and soothed me were his. At a family wedding, when I’d demanded to know why he’d been negative about my writing career, drunk on White Russians, he’d whispered: “You’re doing what I was afraid to.” The next day, when I asked him to elaborate, he said: “You made up the memory.”

My Grandpa Harry died when my dad was exactly my age. Afterwards, visiting him at the cemetery, he walked past the graves of his two beloved medical school professors. I keep hearing the echo of what he’d told me when he came home that day: “All my fathers are dead now.”

Susan Shapiro, a Manhattan writing professor, is author of several books her family hates like Barbie: Sixty Years of Inspiration, Five Men Who Broke My Heart, The Forgiveness Tour, and her writing guide, The Book Bible. Follow her on Twitter at @Susanshapironet and Instagram at @profsue123.