A fiddler on the roof. Sounds crazy, no?

Well, actually, no. Of all the canonical shows of the American musical theater, there is probably none more internationally beloved, more emotionally universal, more instantly iconic than Fiddler on the Roof. You know this, I know this, Martians know this—at least, if they’ve ever been to a Jewish wedding. (Believe me, if there is intelligent life on Mars, they all have a synagogue they won’t set foot in.) So enduring and mythic are the proportions Fiddler has taken in the spiritual life and cultural heritage of modern Jews—American Jews in particular—that it almost seems to have sprung from a sort of collective unconscious of the ages, like the Talmud or even the Bible, composed by some nameless, divinely-inspired author; or depending how seriously you take the orthodoxy of Anatevka, by the fiery finger of God himself.

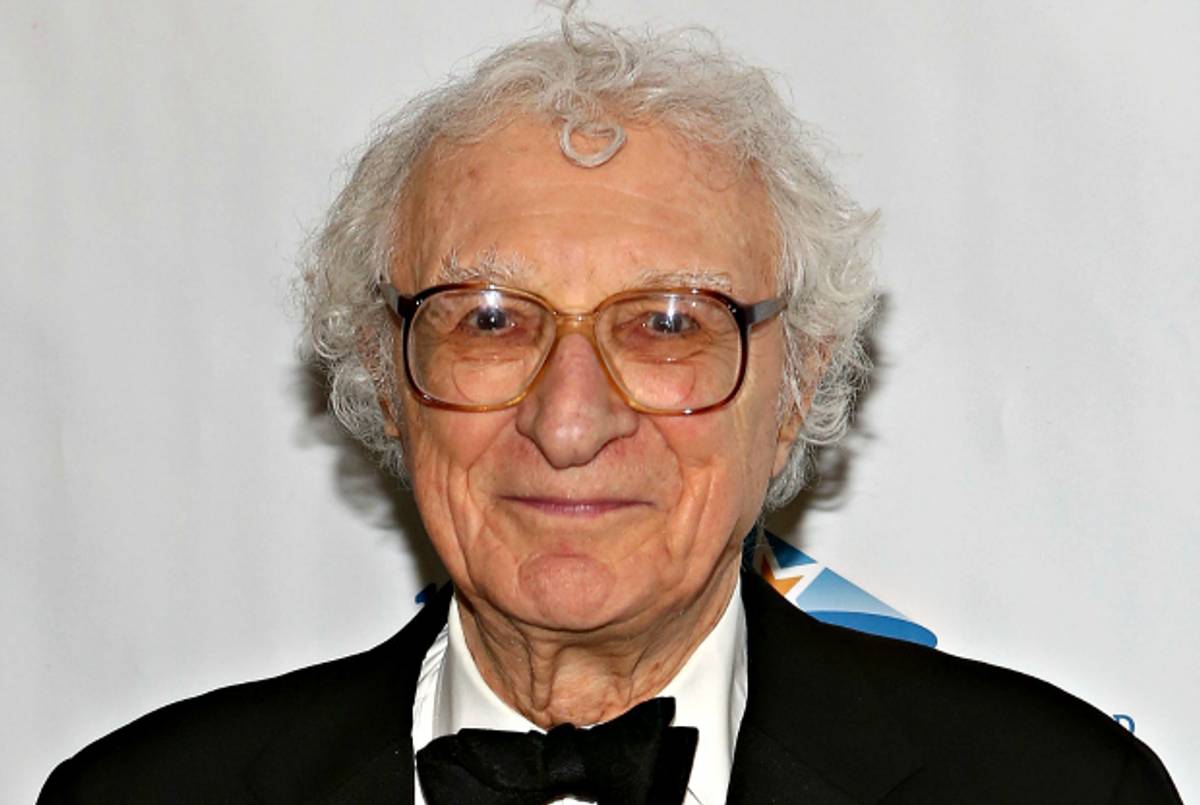

But of course, it wasn’t. The creators behind Fiddler might have passed into the realm of immortality, but they were—and in the cases of some, remain—completely of this world: Jerome Robbins, Hal Prince, Joseph Stein, Jerry Bock, and of course, Sheldon Harnick, the show’s lyricist.

This week at the 92nd Street Y, Harnick, 91, will present To Life! Celebrating 50 Years of Fiddler on the Roof, a musical look into the creative process behind the popular show, as well as a concert revue of its sparkling score, including many scarcely heard before songs that didn’t make it into the final show. It’s a must-see for Fiddler fanatics and musical theater aficionados alike. I caught up with the theater legend Sheldon Harnick by phone this week.

Thank you so much for talking to me. Just to start things off, tell me a little bit about the genesis of the show. Were you and your creative partners looking to do something set in this world and found the source material–Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye stories–to go with it, or did the stories find you?

It started when somebody sent me a novel by Sholem Aleichem, a book called Wandering Stars. I read it and I loved it, and I sent it to Jerry Bock, and then we both sent it to Joe Stein. And Joe said, it’s too big, it’s too complex a novel to put on the stage. But he said, well, since we love the way this man writes, let’s see what else we can find by Sholem Aleichem. So we looked, and we found this book called Tevye’s Daughters, and decided that’s what we wanted to do as a musical. But there was a problem, because a playwright named Arnold Perl had written a play–not a musical, just a play–in three acts, and each of the acts was about one of the daughters. So we had to negotiate with Arnold Perl to get the rights. And as a matter-of-fact, anytime you see a full ad for Fiddler on the Roof, under the title, you will see the words “by special arrangement with Arnold Perl.”

So he must have come out pretty well from that, I guess.

Yes, I think he did!

What about Tevye’s Daughters appealed to you specifically, out of all of Sholem Aleichem’s work?

They’re beautiful stories. There’s great humor in them, they’re very human stories, very universal. And they’re just wonderful plots. We were all very moved by them. So we thought let’s see if we can do them justice on the musical stage.

It’s always interesting to me the way Fiddler came along at what seems like a very particular point in the American Jewish trajectory, like it was culturally the right time to see something explicitly Jewish on the mainstream stage. Do you have any thoughts about why that was?

Well, there had been other shows. Jerry Herman had done a wonderful musical called Milk and Honey, and there were Jewish-themed things on stage from time to time. But I really think the main reason our show was so successful was because of our director, Jerry Robbins. He was obsessed, by this world, by this material. His research was endless, his creativity was in full tilt, and he was really obsessed with doing the show right. He told us that when he was six years old, his family had taken him to Poland, to the area of Europe where their ancestors came from. And he said it was a very moving experience. And then during World War II, of course he heard how the Nazis were exterminating these little towns. So when we asked him to be our director, it gave him the opportunity to recreate that shtetl world, and give it another 25 years on stage.

Tell me a little about your writing process. When you approached a song, did you come up with the lyrics first, or did Jerry Bock come up with music, or was it sort of a combination of the two?

Well, when I was working with Jerry Bock, we had a process that was unique in my experience with people I’ve worked with. Once we knew what the project was about, we would go into our respective studios and begin to work, not together, but alone. And Jerry would come up with song ideas and work on them, and then when he had them to the point where he thought they were finished he’d put them on tape. And eventually, he’s send me a tape with anywhere from ten to twenty numbers on it, and I would listen, and I must say he was very generous, because on any tape, there might be only two or three songs that I thought I could use. But that was how we always started. I waited for him to send me music, and then I would pick two or three songs from the tape, and I would put lyrics to them. And then eventually, I would have an idea for a song where I would just start writing lyrics without music. When our collaboration broke up some years ago, I got very curious about which more often came first in our work, the music or lyrics. So I went through all of our shows, and I made a list of all of the songs, and to the best of my recollection I tried to remember which came first in each case. And I was surprised, because it turned out to be 50-50.

How did the book fit into the process?

The book always came first. The book had to come first, for two reasons. One is that I had to know what the characters were doing that made them need to sing. And the other thing is that as the book writer began to develop the characters, I had to study them and see how they spoke. Because when they sang, they’d have to sound like the same person who was speaking.

That’s incredibly clear in Fiddler. Especially with a character like Tevye, who has all those direct-address monologues to the audience, and then when he sings, he sounds almost exactly the same. It’s the same character with the same thoughts.

Yes. We worked very hard to achieve that.

Do you have a song that’s a particular favorite of yours in Fiddler, or particularly meaningful to you?

There’s a song called “Do You Love Me,” a duet between Tevye and Golde in the second act. I had the idea for it in rehearsal when we were in Detroit for our pre-Broadway tryout, and I went for long walks every day… It took me about a week to write that lyric, and that lyric is not that long. But finally I finished it, and I gave it to Jerry Bock, and I thought it didn’t look like a lyric, it looked like a scene, and I just said, ‘Well, do the best you can.’ So it went into the show and it worked. And then about three days later, I went to see a matinee, and when Zero Mostel and Maria Karnilova sang that song, to my surprise, I suddenly began to sob. I had to leave the theater because I was afraid of disturbing the audience, and I got outside and I thought, why am I crying? And I realized I had written about my parents, and how I wished that they had the relationship that Tevye and Golde had.

What was it like working with Zero Mostel? He was known for his improvisations, and sort of going off-piste, so to speak. How did that affect the show?

That’s a hard question to answer because I have never been able to write the right songs before we go into rehearsal. So I’m always off at home or off in the hotel room during the rehearsal period, and I didn’t get much of a chance to watch Zero work. But on stage, we had a lot of complaints from professional people who saw the show. Audiences generally loved Zero, whatever he did. But professionals would pull me aside and say, “Do you know that Zero’s doing this?” He didn’t add dialogue, but he would change staging. He’d do whatever he wanted, and because he was very funny the audiences loved him.

But one time we had an actual problem. A critic from a Kentucky paper had come to New York and seen the show, and when he went back to Kentucky, he wrote a piece in his newspaper, and it said, “While I was in New York, I saw Fiddler on the Roof. It’s a darling show and I hope you see it someday, but try to see it without Zero Mostel.” He felt that Zero was distorting every scene that he was in. And of course, that was very worrying to all of us, especially to our producer, Hal Prince. So Hal wrote a letter to Zero, which said something like, “Dear Zero, we think you’re a genius and we love everything you’re doing, but every so often you do something that crosses a line and we’d like to be able to talk to you when that happens.” We thought it was a very diplomatic letter, but Zero didn’t think so, and he said, in essence, “Nobody tells me what to do in this show, this show wouldn’t be a success without me.” He was very difficult. But he had his reasons.

What happened—and not very many people know this—is sometime before he was in Fiddler, Zero was run over by a bus. He was rushed to the hospital, but he was conscious, and he heard the doctors saying they had to amputate his leg. And he begged them, “Please do what you can to save the leg, I’m a performer.” So they did. I saw it in his dressing room once, it didn’t really look like a human leg. After about eight months, we got a letter from his doctor, saying: “Mr. Mostel cannot continue to play eight shows a week.” So he was only in the show for about nine months. And then Luther Adler, of the famous Adler family, took over for him, and he was a wonderful dramatic actor, but he wasn’t really right for musicals. His second act was wonderful, but his first act, which is really musical comedy, was weak. So Hal sent him out on the road, and then we got Herschel Bernardi, who as far as I’m concerned, was the best of all the Tevyes we had in New York.

I was just about to ask you who you thought the best Tevye was!

It was Herschel. There have been a lot of wonderful Tevyes since then, but in that original run, in eight years, he was the best.

Is there an actor you would have loved to have seen as Tevye who never played the role?

Yeah. Oddly enough, he’s a British actor named Robert Hoskins. Bob Hoskins. And I would have loved to have seen Geoffrey Rush do it.

It’s not too late for Geoffrey Rush! Let’s talk about the show at the 92nd Street Y, which features many of the songs that were cut from the show.

There were about twenty songs that were cut from the show, or just never used. They were written to be used, and Jerry Bock and I would audition them for Jerry Robbins and the producers, and they thought for one reason or another they weren’t right. For instance, there was one we tried, that was a duet between the revolutionary Perchik and Hodel, called “If I Were A Woman.” It was an argument, but the audience could tell that they were attracted to each other. It was a very effective song and it worked on stage, but while we were in Detroit, Jerome Robbins said, “I’m going to cut that song.” We said, “Why? It works! It gets a big hand!” And he said, “I know it does. It’s a wonderful song. But the show is too long. And I can accomplish the same thing in 30 seconds of dance.”

The original opening of the show was a song called “We’ve Never Missed a Sabbath Yet,” but it was replaced, of course, with “Tradition.” How did that come about?

We would have meetings every week with Jerry Robbins, before we went into rehearsal. And at every meeting, he’d say: “What is this show about?” And we realized that what the show was about was the changing of tradition. It was exemplified by the romances of Tevye’s daughters. One of them by not using the matchmaker, one married out of the faith, they each broke a tradition. And when Robbins realized that, he said, “You have to write a song that will tell the audience what these traditions are.” So we wrote a song called “Tradition.”

It’s probably the most iconic opening in all of musical theater.

It’s a terrific opening. And Jerry Robbins staged the whole thing in about two hours.

It’s such an incredible achievement, that immediate sense of place. You know exactly where you are and who you’re looking at. It’s like “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’” that way.

I wanted to use “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’” but they told me it was already taken!

As the granddaughter and great-granddaughter of butchers, I’ve always been curious about a song I have not heard, called “A Butcher’s Soul,” which of course, is sung by Lazar Wolf.

Ah, that’s a song that I love. In an early version of the show, when Lazar Wolf tells Tevye that he wants to marry his daughter, Joe Stein had written a scene where Tevye says, “Why should I give my daughter to a coarse, crude, butcher? A man like you, a man with no soul?” So we wrote a song for the butcher in which he could define himself. It’s a wonderful song, and it always worked, but Jerry Robbins said, that scene needs to be about Tevye, and not the butcher.

You mentioned universality earlier, and that’s such an interesting thing with Fiddler, because it’s such a specifically Jewish show. But people seem to relate to every aspect of it all over the world.

We wanted to make it universal. And our reward was that every time you open a show, every sixteen weeks or so they would have to do a special performance for the other actors who are working. When we did the first one, I was standing in the back, and at the intermission, Florence Henderson came running up the aisle and she said to me, “Sheldon! This is about my Irish grandmother!” And I thought, that’s exactly what we wanted to accomplish. And we did.

Previous: Fiddler on the Roof Heading Back to Broadway

Watch Josh Groban Play Tevye in His High School Production of ‘Fiddler on the Roof’

Related: The Aristocrats

Rachel Shukert is the author of the memoirs Have You No Shame? and Everything Is Going To Be Great,and the novel Starstruck. She is the creator of the Netflix show The Baby-Sitters Club, and a writer on such series as GLOW and Supergirl. Her Twitter feed is @rachelshukert.