Beware the Do-Gooders

How a new class of capitalists couched their profit-seeking in the language of social justice and altruism

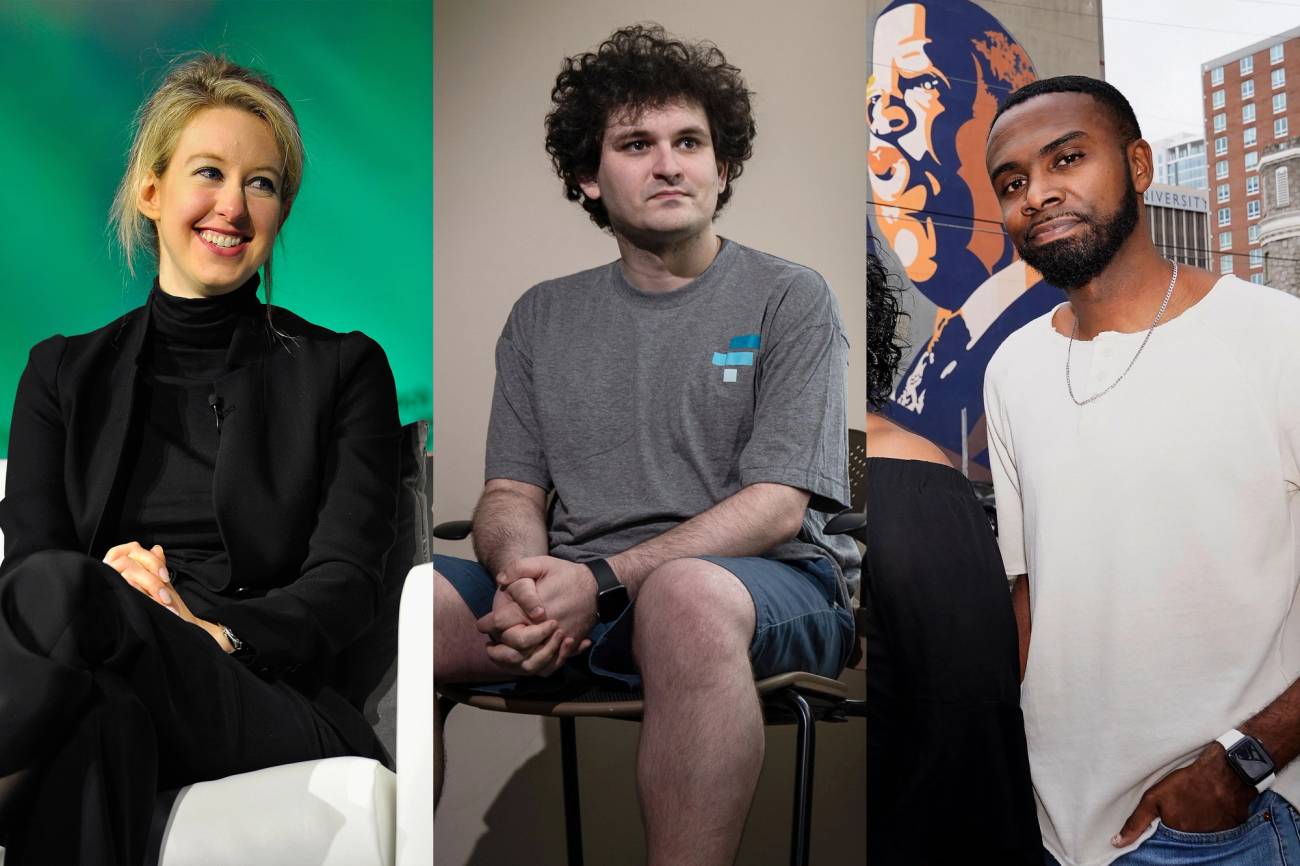

Gone are the days when villains dressed the part and Wall Street vampires suited up like Gordon Gekko. These days, an American who wants to avoid being swindled needs to watch out for the T-shirt-clad do-gooders spouting the proper politics and pieties while claiming that they only want to save the world. The recent collapse of Sam Bankman-Fried’s cryptocurrency empire, FTX, fit the larger pattern: it was a massive financial scam marketed as a moral cause that got away with it by flattering the high priests of the press and offering elected officials promises of gifts and donations.

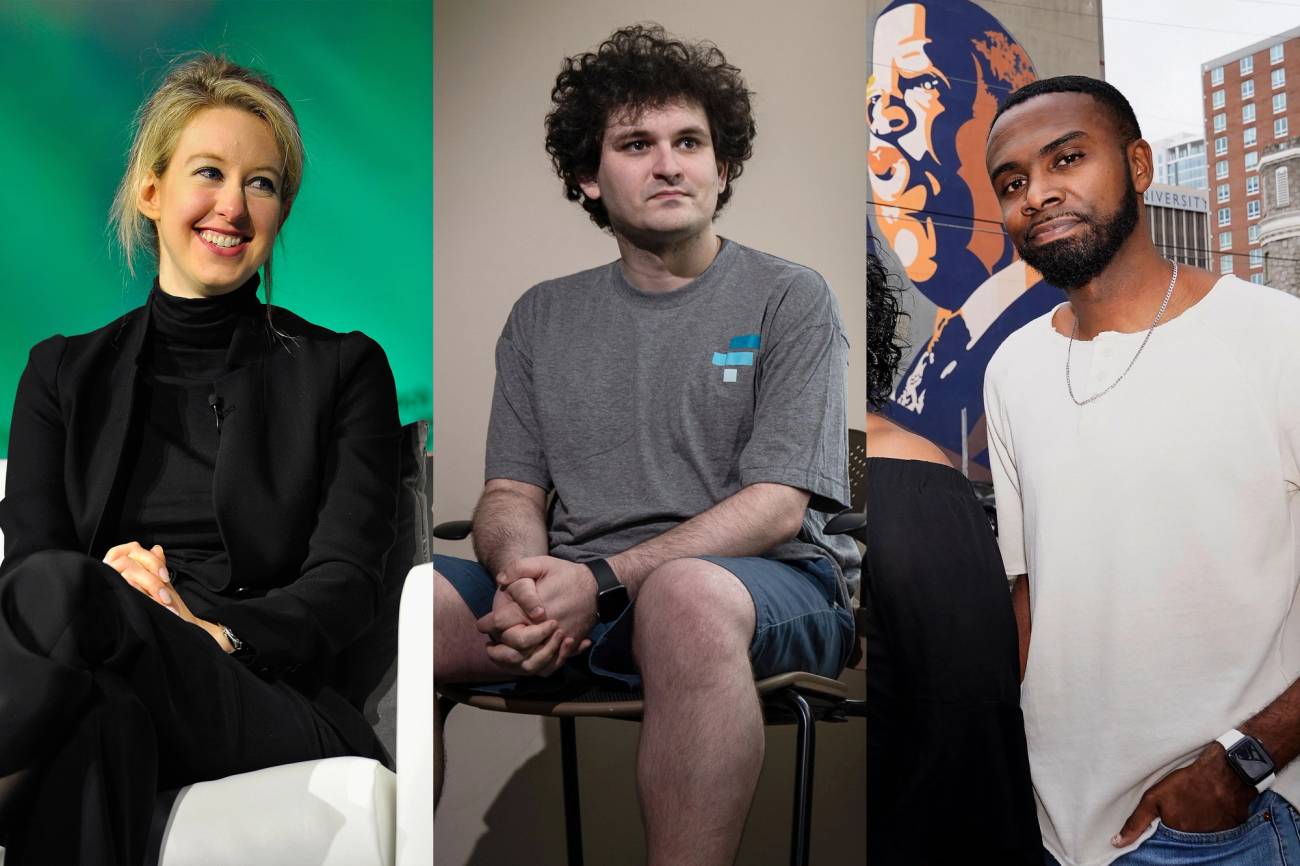

Before FTX, it worked wonders for Theranos, WeWork, and the Black Lives Matter Global Network. Millions and then billions of dollars were poured into corporate vessels promising change, their founders cozy with a media that long ago abandoned its role as a check on the nakedly self-promotional claims of the rich and powerful.

With the financial and philanthropic worlds now firmly wedded, there are even bigger bubbles yet to burst, like the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) funds that consulting powerhouse McKinsey estimated had a total global value of $2.5 trillion midway through 2022. The conditions that allowed for a $10 billion crypto empire to vanish into thin air have only become more conducive to the do-good grift, like a virus replicating itself inside a host’s body.

As a public face for the effective altruism movement, Bankman-Fried’s particular brand of swindle was different in detail but not in kind from the snake oil sold by Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes. Holmes was sentenced last month to 11 years for charges related to misleading investors about the fact that her $9 billion genetic testing startup was a fraud with no ability to do the things it promised. A similar pattern of financial swindling, albeit on a smaller scale, has taken place at the Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation. In a new lawsuit filed in September, more than 25 local BLM chapters sued the foundation’s current leader, Shalomyah Bowers, for allegedly “devising a scheme of fraud and misrepresentation” to siphon out more than $10 million from donor coffers. Bowers was brought into the organization by BLM co-founder Patrisse Cullors before Cullors stepped away amid her controversial spending of $3.2 million on four luxury residential properties. Clapping back at the local BLM chapters, Bowers accused them of perpetuating the “carceral logic and social violence that fuels the legal system,” for reporting his alleged grift.

The child of two Stanford law professor parents who debated the merits of political activism at the kitchen table, Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) was steeped in the do-gooder ethos from a young age. He first attended an elite prep academy and then MIT, where he fell in with Will MacAskill, an Oxford-trained philosopher looking for recruits to his new effective altruism (EA) movement. Rooted in the utilitarian philosophy of Peter Singer, EA practitioners injected philanthropy with a dose of financial optimization by claiming a moral obligation to make as much money as possible for the sake of giving it all away. The opportunity to appear entirely noble while accumulating a fortune apparently appealed to SBF, who took up the EA mantle as he moved on to the New York trading firm Jane Street before hanging out his own shingle with what would soon become the FTX crypto exchange.

“SBF’s purpose in life was set: He was going to get filthy rich, for charity’s sake,” went a profile on the website of Sequoia Capital, the venture fund that would soon plow $214 million into FTX. But even a small fortune wasn’t going to fully quell SBF’s itch to truly make his mark. As the Sequoia profile noted, SBF “needed to take on a lot more risk in the hopes of becoming part of the global elite.”

Bankman-Fried’s timing was fortuitous—the EA movement itself was growing in stature among the global aristocracy he aspired to join, and which already included high profile practitioners like Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz and LinkedIn leader Reid Hoffman. As SBF’s crypto exchange grew, so too did the number of articles depicting his beneficent intentions to save millions of lives with malaria interventions, $2,000 at a time. The signs that SBF was using the language of altruism as a cover for a naked pursuit of power were ignored. Much was made of SBF’s dogged work ethic and modest lifestyle—how he slept on a bean bag beside his computer in a house with nine roommates. Little scrutiny was given to the fact that the house was a $40 million condo in the tax haven of the Bahamas, or that he shuttled himself around on a private jet.

The growing gap between the truth and the reality of SBF’s practice was as obvious to those within the effective altruism movement as it was to his own employees. “The problem was that there was a story about his frugality that was something adjacent to a lie,” one EA movement figurehead told The New Yorker. Within Alameda, the investment arm of FTX, SBF pushed his staff to take on the highly speculative crypto derivatives that other exchanges wouldn’t touch because they seemed so obviously designed to fleece ill-informed investors. “He was so excited about these products that are just so predatory―they are blatantly short-term gambling, and in the long term the house wins,” an Alameda staffer told the same The New Yorker reporter. “You can talk about ‘means justify ends’ stuff … but this was pretty clearly just, ‘We want to make this product so that we can essentially scam people out of their money and then give it to charity.’” Of course, the “give it away to charity” part of the equation ended up being less essential than the scam. For instance, of the $95 million that the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan invested in FTX, it was reported that SBF took a significant portion not for EA-branded charity but rather for his own personal use.

For those charged with asking questions and holding power to account there’s an increasing reluctance to exercise that responsibility.

It shouldn’t have taken more than a reporter’s quick look around the FTX conference table, with the Caribbean ocean view off in the distance, to wonder what, exactly, SBF was up to. He’d carefully courted officials from the regulatory offices meant to oversee his business, bringing in Mark Wetjen and Jill Sommers from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission to serve as his head of FTX U.S. regulatory policy and as a member of his FTX U.S. derivatives board, respectively. There were red flags in his Washington connections just the same. In March 2022, the so-called Blockchain Eight―a group of four Republican and four Democratic House representatives―sought to stall a new SEC probe into FTX and several other crypto firms. Of those eight officials, five had received donations directly from FTX staff, including more than $500,000 to North Carolina’s Rep. Ted Budd from a super PAC started by a top deputy of SBF’s at FTX, Ryan Salame. Though SBF has been described as a major donor to progressive candidates, he was giving lavishly to both sides of the aisle. Between SBF’s donations through dark money groups and those passed on by Salame, FTX contributed more than $60 million to Republican candidates this past election cycle.

Is the blame, then, for the total absence of scrutiny of FTX, or the scandals that preceded it, a failure of the fourth estate, or the government agencies presumably tasked with preventing industrial strength fraud and theft? Might it be both, and something else besides? For those charged with asking questions and holding power to account there’s an increasing reluctance to exercise that responsibility. It’s no mystery why, given the animus directed against those who do inquire about concentrations of wealth and power behind causes branded as socially beneficial. Just look at anyone who’s ever raised an eyebrow at the massive amount of money George Soros has plowed into district attorney elections to support stridently progressive candidates and then been called an antisemite.

Now, though, there’s a cold logic that’s starting to assert itself among those who must prioritize their fiduciary responsibilities above the feel good shoveling of money into a furnace labeled good cause. The world’s largest mutual fund manager, Vanguard, said last week that they were cutting ties with Net Zero Asset Managers, a climate-focused ESG alliance of investment firms with roughly $66 trillion in managed assets. “We have decided to withdraw from NZAM so that we can provide the clarity our investors desire,” said Vanguard, which manages $7 trillion in assets. That move comes after the chief financial officer of the state of Florida said earlier this month that he was removing the $2 billion of the state treasury portfolio invested in Blackrock because of their allegiance to ESG over their duty to the bottom line. “We are disturbed by the emerging trend of political initiatives like this that sacrifice access to high-quality investments and thereby jeopardize returns, which will ultimately hurt Florida’s citizens. Fiduciaries should always value performance over politics,” Jimmy Patronis, the CFO said, echoing a move made by the Republican-controlled treasuries in Missouri and Louisiana, which took out roughly $1.2 billion collectively from Blackrock in October for similar complaints.

That mutual fund managers and financial officers in oil-rich states both see more money to be made away from ESG virtue signaling speaks as much to the incentives pegged to fossil fuel profits as it does the loosening of the grip ESG has had on the financial sector. But moralizing investment ventures are no more likely to disappear completely, as Silicon Valley’s most noble-minded hucksters continue to reinvent the do-good scheme under refreshed logos and branding. After WeWork founder Adam Neumann’s attempt to “elevate the world’s consciousness” with his shared-office business led to a failed IPO and a scandalous resignation from his own company, he was back on his social change grind this summer, raising $350 million from Andreessen Horowitz for Flow, a real estate startup promising branded apartments and communities.

On Friday, Crain’s New York reported that the ratings firm Fitch projected that WeWork, Neumann’s first attempt at transforming society, was on the brink of bankruptcy, with only 12 months of cash on hand to offset 18 months of losses on the horizon. The largest commercial tenant in New York as of 2019, WeWork could simply cancel out $700 million in leases during bankruptcy, Fitch noted, which wouldn’t matter much for Neumann, who would still have his $1 billion golden parachute even after leaving a bloodbath to clean up at all the abandoned offices that once promised communal harmony.

A previous version misattributed a $350 million investment by Andreessen Horowitz to Flowcarbon when it was made to Flow. Both start ups were co-founded by Adam Neumann and backed by Andreessen Horowitz. The Flowcarbon crypto token is not related to the Flow real estate venture.

Sean Patrick Cooper is a journalist who has contributed narrative features and essays to The New Republic, n+1, Bloomberg Businessweek, and elsewhere. His first book, The Shooter at Midnight: Murder, Corruption, and a Farming Town Divided will be published in April 2024 by Penguin.