The Biden Administration Redefines Antisemitism

And excludes today’s most pernicious form of Jew-hatred

Puffin’s Pictures/Alamy

Puffin’s Pictures/Alamy

Puffin’s Pictures/Alamy

Opposing antisemitism is easy, because everyone is on your side. Already 100 years ago, Henry Ford’s Dearborn Independent, in its notorious series “The International Jew,” complained that the term “antisemitism” is “used indiscriminately and vituperatively” against those who just want to “discuss … Jewish world-power.” Sophisticated antisemites do not come out and admit it. So to fight antisemitism, one must first define it.

This is even more challenging today, when the general anathema to antisemitism in polite society makes “anti-Zionism” a convenient and common substitute. Yet recent actions by the Biden administration show that the problem of antisemitism manifesting as “anti-Zionism” requires further clarification. By morally legitimizing the position of those who call Israel a “fascist” nation or an “apartheid state,” the Biden administration has upended, quietly and with little notice, the governing consensus on what constitutes antisemitism.

The only broadly accepted definition of antisemitism today is the working definition of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), an intergovernmental organization of over 30 member countries. After several years of consultations with academic experts from around the world, including debate about the role of “anti-Zionism,” IHRA unanimously adopted its definition in 2016. Crucially, it states that “anti-Zionist” or “anti-Israel” sentiments can be “manifestations” of antisemitism. IHRA’s definition provides several illustrations: claiming Israel’s existence is illegitimate; the regrettably widespread practice of “applying double standards” to the Jewish state; or “requiring of it a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation.”

To be clear, the IHRA does not equate criticism of Israel with antisemitism. It explicitly states that criticism of Israeli government policies is legitimate, as with any country. However, condemning Israel based on standards or supposed norms that are in practice applied only to the Jewish state may cross over into antisemitism. Even for such double standards, the IHRA definition only creates a presumption that must be corroborated by other contextual factors.

Opponents of the IHRA definition claim it is designed to silence ordinary criticisms of Israel. A number of such organizations wrote in a recent letter to the United Nations that “the IHRA definition has often been used to … chill and sometimes suppress, non-violent protest, activism and speech critical of Israel and/or Zionism, including in the US and Europe.” Yet IHRA stresses that its working definition is not legally binding, and its definition’s only role is to help create a consensus on what constitutes antisemitism—not how to regulate it. Under the First Amendment, the government must not, under almost all circumstances, restrict antisemitic speech (or other forms of hate speech), and can only deal with actual discriminatory conduct, such as boycotts. Similarly, principles of representative democracy demand that members of Congress should be permitted to say even antisemitic things, including about Israel (though this does not mean such statements should be rewarded with choice committee assignments).

The IHRA definition struck a chord, and has been formally adopted by at least 39 countries, including the U.S., and endorsed by the European Union and European Commission, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, most U.S. states, and a vast number of ideologically diverse jurisdictions, universities, and political entities around the world.

Not surprisingly, the IHRA definition is opposed by those who wish to engage in precisely the kind of anti-Israel double standards that the definition seeks to identify. In an effort to confound or counteract the legitimacy and clarity of the IHRA working definition, a few other groups have offered alternative definitions that greatly minimize the role of Israel-focused antisemitism.

One such effort is the Nexus Document, a project hosted by Bard University. The Nexus definition differs from IHRA primarily in its treatment of Israel-focused conduct. Nexus does not regard as presumptively antisemitic either the questioning of the basic legitimacy of Israel’s existence or the application of double standards to Israel. According to Nexus, such views may have legitimate grounds.

The differences between the IHRA and Nexus definitions of antisemitism don’t stop there. Unlike IHRA’s adoption by a wide range of countries (including many states that are often sharply critical of Israel), not one country or governmental entity has adopted the Nexus Document. The IHRA definition was developed by an international group of scholars not known for their views on Israel or their politics one way or another. The Nexus advisory board, by contrast, is overwhelmingly left-wing and includes people like the head of J Street. Members of Nexus’ advisory board have described Israel as “fascist,” denounced it as an “apartheid state,” and justified those who say it should have never existed.

While IHRA has become the global benchmark, the narrow Nexus definition has languished in total obscurity—that is, until the White House suddenly announced its “welcome and appreciation” of the Nexus Document in May, while still “embracing” IHRA. Nexus leaped from the discussions of like-minded academics straight into a White House policy document. While the IHRA definition remains the only one officially used by the government, the White House’s National Strategy harms efforts to respond to antisemitism by referring to two different, and fundamentally contradictory, definitions.

Just as the classic blood libel resonated with the theological preoccupations of earlier ages, today’s claims resonate with the ethnic justice concerns of our times.

The central claim of Nexus and other critics of the IHRA definition is that even vicious attacks on Israel should not be considered antisemitic because they are not about Jews per se, but about the Jewish state’s governmental policies. It would be lazy to dismiss this possibility out of hand. Let us examine these attacks first in the perspective of history and then in light of some of the “reasons” suggested by Nexus.

The obsessive focus on the supposed wrongs of Israel has resurfaced across an amazing array of cultures and epochs. From the Romans to the Crusades, the Reformation to the Inquisition, National to International Socialism. The justifications change but the target remains the same.

It is an illusion that antisemitism amounts to such only when it presents as pure unreasoned Jew-hatred or as stereotypes and “tropes.” Antisemitism has never been merely a hate-filled emotional state, it has always been what some academics have called a “pseudo-explanatory political theory.” The most effective antisemites have always sought to justify their bigotry by claiming they simply object to the bad things Jews do to the world: The Jews were hated for producing Jesus and for not accepting him; they were hated as representatives of global capitalism and of international communism. Even Hitler—hardly subtle about his hatred of the Jews—cited policy reasons: They have “the two million dead of the [First] World War on their conscience,” and “they undermine the economies of countries leading to poverty.”

The accusations leveled against Israel often resemble antisemitic claims made throughout history. Instead of the Jews being accused of killing gentile children, Israel is accused of deliberately killing Palestinian children; instead of Jews being accused of causing plague among gentiles, Israel is accused of causing disease among Palestinians. And the accusation of “apartheid” is a modern blood libel—an absurd “Big Lie” that cannot be rectified by mere refutation. Just as the classic blood libel resonated with the theological preoccupations of earlier ages, today’s claims resonate with the ethnic justice concerns of our times. That today several members of Congress can level such libels against the Jewish state without facing sanctions from their party demonstrates how dangerous “polite” antisemitism is.

The general anathema to antisemitism in polite society makes ‘anti-Zionism’ a convenient and common substitute.

A definition of antisemitism is inadequate if it cannot capture a phenomenon of such breadth, persistence, and significance in the treatment of Jews. Nexus argues, however, that discriminating against Israel should not be seen as presumptively bad because there exist good “reasons … for treating Israel differently.” Nexus cites two purported reasons—that people “care” more about Israel, and Israel’s receipt of U.S. military aid.

“Caring” of course is not a reason but a feeling, making this explanation circular. It is undeniable that much of the world “cares” a great deal about Israel, but such hostile caring is itself the phenomenon that requires explanation. Nexus suggests that perhaps someone’s “personal or national experience may have been adversely affected by the creation of the State of Israel.” This is a woefully inadequate account. If contemporary anti-Israel sentiment were limited to, say, Palestinians, we would not be having this hearing. This cannot explain the “caring” of large, impersonal institutions like the United Nations, and supposedly neutral groups like Amnesty International or Human Rights Watch, which lack “personal or national experiences.”

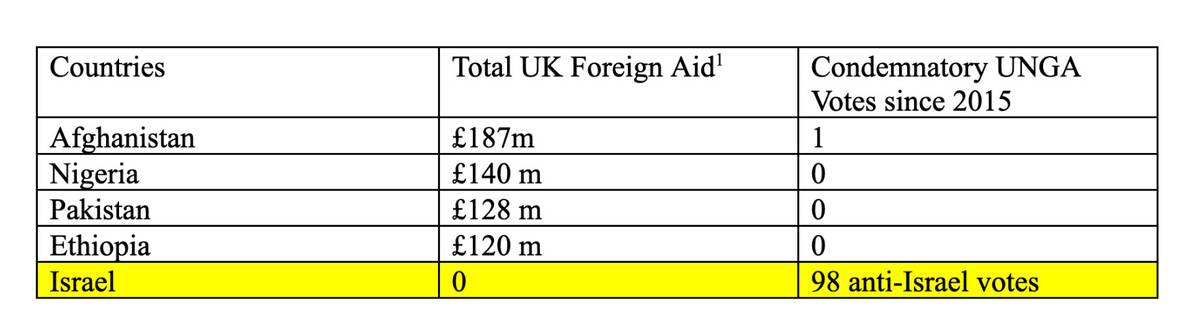

The second justification Nexus cites is that Israel receives a significant amount of “American aid.” To be sure, criticizing U.S. aid to Israel is itself legitimate—but it hardly accounts for the double standards against Israel. For one, heightened hostility to Israel’s existence is not solely or even primarily an American phenomenon. IHRA grew out of European anti-racism monitoring efforts. European countries do not provide significant foreign aid to Israel, but the same kind of double standards are present there (see Table 1). Nexus wants us to believe that those Americans who oppose Israel, just as their European counterparts do, happen to do so for a distinctive American reason—an amazing coincidence.

Attempts to insulate delegitimization of Israel from accusations of antisemitism have no adequate response to the perfect segue from prior modes of Jew hate to the similarly singular hostiilty the Jewish state has received from the international community, from its creation until today. In anti-discrimination law, it is well established that using a proxy for a target group can still be discriminatory. And everyone agrees that countries can be proxies for their majority population—indeed, this was precisely the argument asserted against President Donald Trump’s immigration restrictions on several Muslim-majority countries.

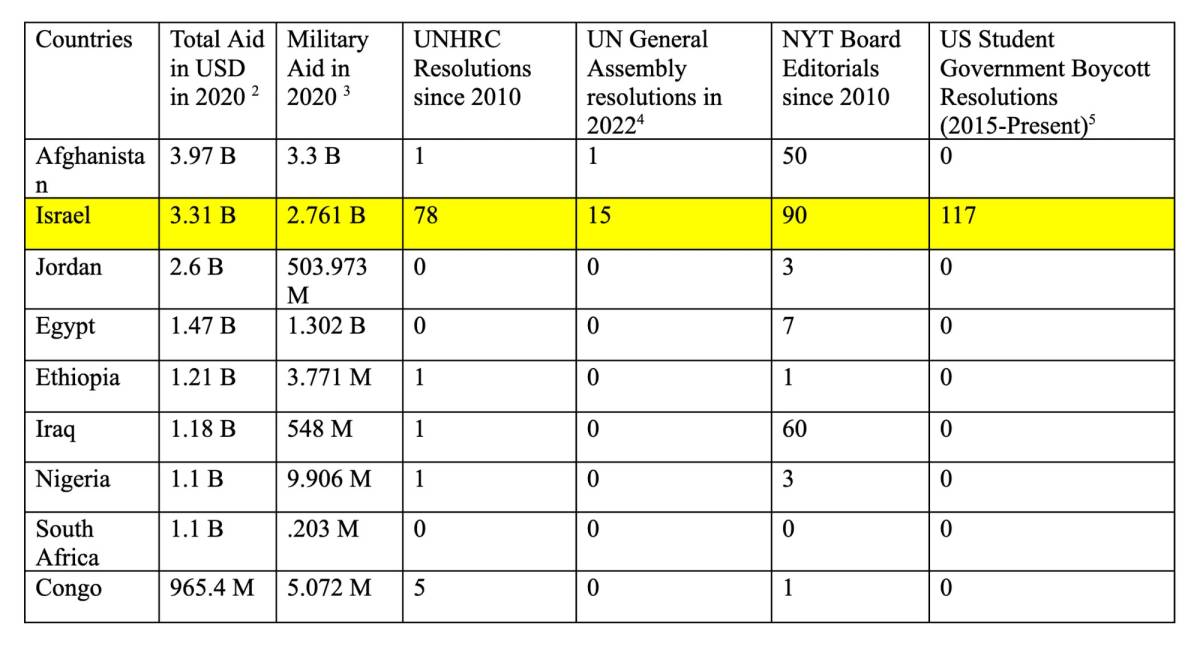

The obsessive hostility to the Jewish state cannot be empirically explained by reference to its policies. For example, Table 2 compares leading recipients of U.S. foreign aid with various indications of domestic and international opprobrium—there is no relationship. Foreign aid cannot explain the broad phenomenon of extreme hostility to Israel.

It must be some other factor. Calling it antisemitism says nothing about the subjective psychological state of the antisemite—they likely experience themselves as heroes, not haters. But labeling particular forms of demonization as antisemitism is crucial to properly understand it as part of an ancient, global, relentless phenomenon.

Eugene Kontorovich is a professor at the George Mason University Scalia Law School and the director of its Center on the Middle East and International Law. He is also the head of the international law department at the Kohelet Policy Forum, a think tank in Jerusalem.