An iron law of the internet is that it is only a matter of time between the creation of a social media platform and it being used to spread anti-Semitic conspiracy theories. In the case of Clubhouse, an invite-only, communal, voice-chat app popular among the Silicon Valley set, we now know exactly how long: The audio-based social network isn’t even publicly available yet, and has already had its first anti-Jewish eruption.

Clubhouse, which is currently valued at $100 million, is an exclusive app that allows users to participate in topical voice conversations controlled by the moderator who launches them. Its approximately 10,000 users include everyone from venture capitalist Mark Cuban to actors Jared Leto, Ashton Kutcher, and Kevin Hart. The platform’s audio-based culture offers a human touch and sense of interpersonal connection that its text-based competitors lack. At the same time, the app’s dynamic freewheeling nature poses unique moderation problems, as became evident this week.

On Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, a group of predominantly non-Jewish moderators convened a chat room on Clubhouse titled “Anti-Semitism and Black Culture.” The very framing of the conversation betrayed that it was not being run by those well-versed in the sensitivities of the subject. First, the title pit two minority communities against each other, rather than couching the issue carefully and constructively. Second, there was the date—Yom Kippur—an unintentional oversight that ironically underscored that the people starting this conversation desperately needed to have it, but also weren’t remotely qualified to lead it.

Unsurprisingly given the discussion’s charged framing, it quickly became one the most popular rooms on the exclusive platform, drawing 350 simultaneous users, and hundreds more who filtered in and out over the course of the multi-hour Monday conversation, including investors and people who work for Clubhouse.

The discussion began constructively, but quickly devolved into a stream of common anti-Semitic tropes about Jewish money, economic and political domination, and the Holocaust—or as one Jewish attendee put it, “an airing of grievances against Jews.” Audio provided to Tablet by a non-Jewish participant of color who was deeply troubled by what they heard features speakers continuously equating Jews with “whiteness,” erasing the experiences of nonwhite Jews—some of whom were in the room—and of Jews in general at the hands of white supremacists. One non-Jewish participant repeatedly declared that Jews and Blacks do not have the “same enemy,” apparently unaware of the alt-right marchers in Charlottesville who chanted “Jews will not replace us,” or the racist gunman who massacred the congregants of Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue. Jews were continually stereotyped as uniformly wealthy, and presented “as the face of capital,” according to several Jewish and non-Jewish participants present. “Multiple individuals justified anti-Semitism by saying it was a way to protest against capitalism,” reported a non-Jewish attendee who spoke to Tablet.

“Part of the central claim was that the Black community deserves reparations, while the Jewish community does not, because the Jews control the banking system, and as a result, the Holocaust was a primarily economic act and not based on race or faith,” explained one Boston-based entrepreneur. “So kind of trafficking in basic anti-Semitic stereotypes.”

One participant named Carlyle claimed that World War II was fought on behalf of Jews, implying Jewish political control of American politics and war-making. (In reality, Roosevelt rebuffed the desperate entreaties of the Jewish community to rescue Jews from the Holocaust and only entered the war after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor.) A speaker insisted that they could not be an anti-Semite because they were also a Semite—“anti-Semitism” is a term that was popularized by German anti-Jewish activist Wilhelm Marr to give his Jew hatred a scientific veneer, and has never referred to non-Jews—and when Jews tried to correct his claims, they were accused of trying to “weaponize anti-Semitism” to silence him. (In actuality, the people who weaponize anti-Semitism are anti-Semites.)

Several other users repeatedly expressed anti-Semitic myths pertaining to the State of Israel, claiming that they were merely anti-Zionist and not anti-Semitic. “Palestinians are essentially enduring mass genocide,” said one in audio obtained by Tablet. (In fact, the Palestinian population has increased fourfold since Israel’s founding in 1948, according to the official Palestinian Bureau of Central Statistics.) Multiple participants claimed that American police learned how to enact violence on African Americans from the Israeli Defense Forces. “We still never talk about the IDF training police officers that are killing Black kids,” said one. (This anti-Semitic canard, which offloads the blame for centuries of American racial violence and police abuse onto unrelated Jews thousands of miles away, has resurfaced with the murder of George Floyd, and been exhaustively debunked by journalists.)

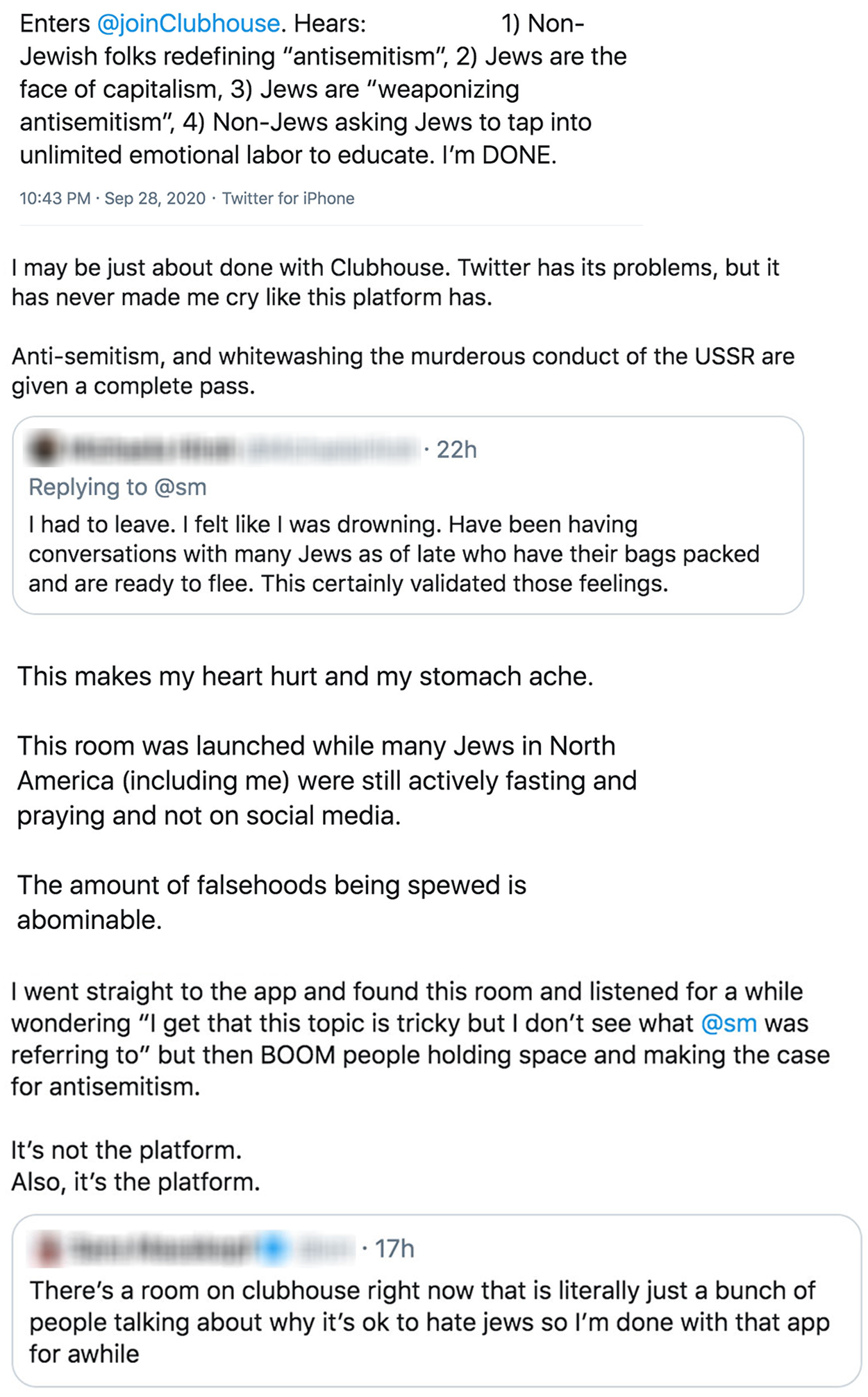

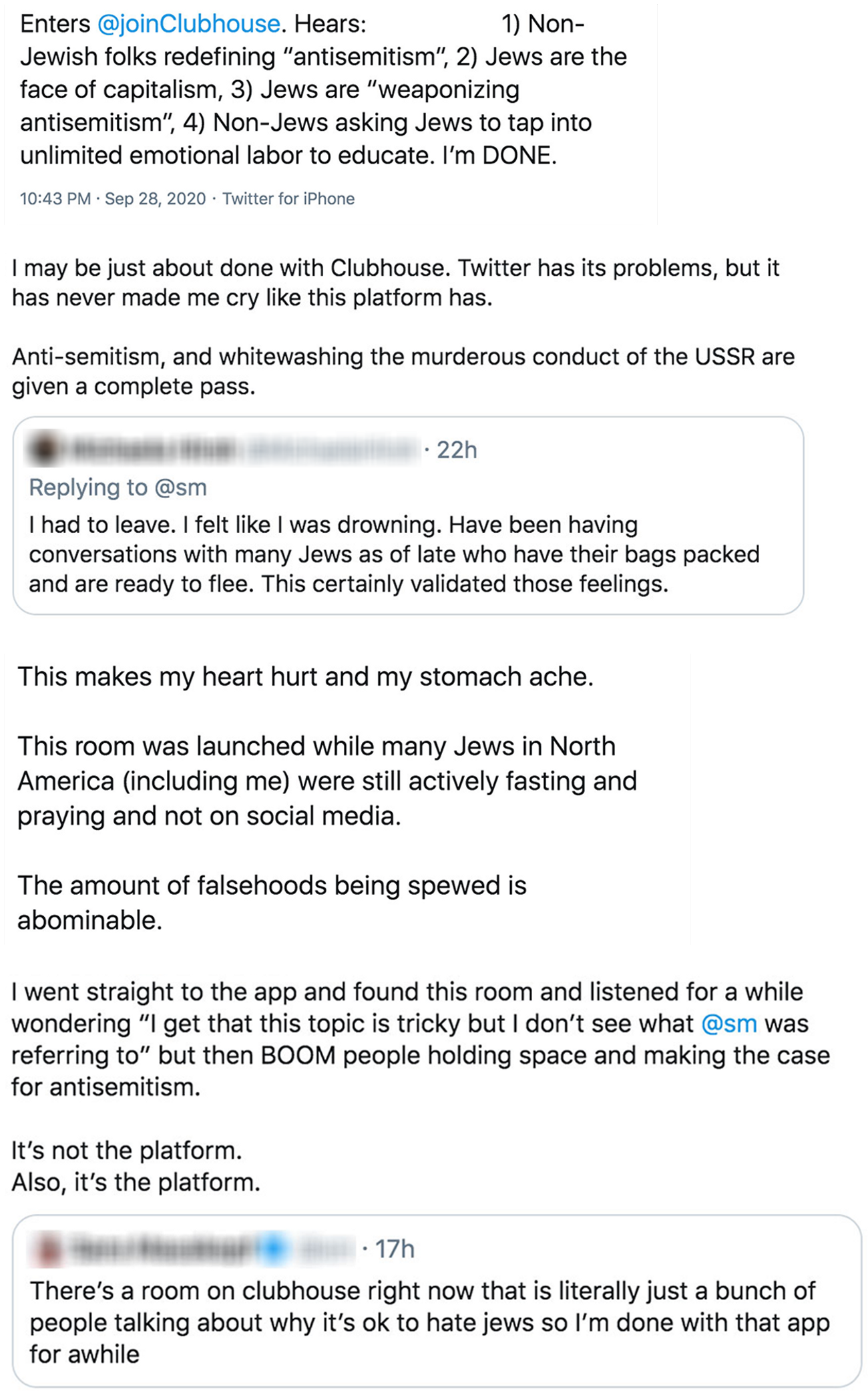

Just as troubling as these outbursts was the fact that they largely went unanswered. A small number of Jews, several having just logged in after Yom Kippur, attempted to interject their perspective into the conversation, but they were quickly overwhelmed by the torrent of misinformation, which continued to flow unhindered by the moderator. “People did refute things, and people did present counterarguments, and they did object to certain things, but not in a way that really signaled to enough of the audience to make people feel that this wasn’t OK,” said coffee entrepreneur Nick Cho. Ultimately, most Jewish participants left the room.

“It was the classic sort of thing where someone says, ‘I’m not racist but’ and then says exactly what the racists are saying,” recounted Cho. This mixed poorly, he said, with the “youth and inexperience” of the chief moderator, anarchist activist Ashoka Finley, who allowed such users to hold the floor rather than challenge them. “It creates a certain kind of energy that either you’re prepared for or you’re not.”

As a Jewish participant named Julian explained in a follow-up conversation with the moderator, “the thing I kept thinking is imagining a room where it was ‘Asian people and anti-Blackness’ and six, seven, eight, nine, 10 different Asian people articulating what their problem was with the Black community. And if that happened, I would think it was super f—ed up and I would be incredibly annoyed that a moderator would allow that to go on. So I feel like that theme got going and there were multiple times to stop it, and it was disappointing that it didn’t get stopped and it just kept going and going and going and going.”

Or as another Jewish participant put it to me afterwards, “everyone’s like ‘punch a Nazi’ until it’s time to stick up for Jews, and then everyone’s silent.”

Finley later apologized on Twitter to “anyone who felt threatened or harmed by anything said in the CH room I started tonight.”

Although this was a particularly high-profile instance of anti-Semitism on Clubhouse, Jewish users said that it was not an isolated incident, merely a more noticeable one. “I have never heard the Rothschild and Fed conspiracies mentioned so many times in my life as I have in the past two months on this app, across rooms,” said one. Clubhouse is currently in beta, and hasn’t yet been rolled out to the general public. The question is: Can it adjust to make situations like these less likely to recur?

Users were split on the subject. Some argued that better moderation in real time, enabling individuals to flag problematic content, could improve the platform. Right now, one participant in the anti-Semitism discussion noted, “there’s no ability to real-time report. Folks were reporting [the anti-Semitism conversation] the entire time, but the way reporting works in this app is that it records audio that gets fed into a customer service queue that gets responded to days later … They just have not invested in community moderation.”

Another user suggested that the best solution might be for attendees to police their own platform, and to be more responsible about which sensitive subjects they broach and how: “I would love to see the ability to close a room if enough participants vote to do that. I would hope that individuals don’t take on topics as delicate as this without education, forethought, and care. But this is the internet and that’s a big ask.”

But others were more pessimistic about Clubhouse’s prospects. “It’s not the social network’s problem, it’s a human problem,” said Cho. “There is a point at which you can’t engineer your way out of the human condition.” Hearing someone’s voice makes conversations on the platform feel more immediate, he explained, but also more threatening when they go off the rails. “The thing that makes it really wonderful and creates all those connections is exactly the thing that makes it more damaging when it’s something that’s not cool,” Cho continued. “I believe ultimately it’s not going to last as a platform as a result. I don’t think that this concept can withstand humanity.”