CUNY Schools Jews on the New Race Regime

Skipped by the university’s chancellor for the second time, Thursday’s hearings to address allegations of pervasive student and faculty antisemitism ended in bitter stalemate

Of all the signs that the Jewish community’s political influence has waned in New York City, perhaps none has been as stark as the City University of New York’s frequent spasms of open distaste toward the Jews, many of them Mizrahi, middle class, or foreign born, who attend its dozens of colleges and graduate schools. The CUNY law school faculty unanimously endorsed a student council Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions resolution targeting Israel in May. Those students had also chosen Nerdeen Kiswani, founder of a radical activist group committed to “globalizing the Intifada” against Israeli Jews and their sympathizers, as one of their commencement speakers. The Professional Staff Congress, a union representing 30,000 CUNY employees, had passed a resolution in 2021 condemning Israel for the “massacre of Palestinians” and stating the union would consider an endorsement of BDS sometime in the near future.

Even if one doesn’t believe that repeated, organized, and highly selective attacks on the world’s only Jewish state are antisemitic, Jewish students and faculty have often reported a climate of stifling hostility that has forced them to hide outward signs of their Jewishness, and made it impossible to hold or promote even neutral events like Holocaust commemorations. An engine of social mobility for generations of Jewish New Yorkers had become a place where one of the city’s largest ethnic minorities no longer felt welcome. Like the high quality of the municipal tap water, CUNY is one of the last points of pride in New York City’s rapidly declining public sector. But to its critics, the university administration doesn’t care about the antisemitism in its midst, or even recognize it as a problem.

Recourse lies with the few remaining elected representatives inclined to do something about the plight of the average New York Jew, who isn’t particularly rich, powerful, or cool, and holds the unhip belief that Israel should exist. The state of New York is in danger of losing its last Jewish member of the House of Representatives; meanwhile the city’s most powerful elected Jew, Comptroller Brad Lander, is a progressive from Brooklyn’s brownstone belt, someone notably at home in the bourgeois activist world of the anti-Zionist Jewish Voice for Peace and IfNotNow. The charge against CUNY’s alleged complacency is instead being led by one of the city’s least powerful elected Jews, at least on paper: A Ukrainian-born, 37-year-old woman who is one-fifth of the 51-member City Council’s Republican minority.

Inna Vernikov stood at the base of City Hall steps on Thursday morning in front of rows of activists in blue #EndJewHatred T-shirts. In the back, a man in a blue Keep America Great hat cradled a small dog; on the other side of the plaza facing New York City’s beaux-arts capitol building, perhaps the entire male membership of the Neturei Karta Hasidic sect chanted its predictable anti-Zionist slogans, hoisting the same signs they’ve been bringing to events like these for most of the past several decades. Above Vernikov, a trio of differently patterned Pride flags hanging from a stone balustrade suggested the city had now come under the control of a coalition of very colorful militia groups. This was a typical New York circus, complete with a pro-Israel demonstrator who introduced himself to me as a retired NYPD officer and longtime clown. But the petite Vernikov is a figure before whom nonsense evaporates.

“We have a major problem in this city,” Vernikov began, “a culture of antisemitism that’s engulfed our college campuses.” Vernikov has shoulder-length hair that is almost hypnotically black; her nails were painted the same deep white as her jacket. She delivered her remarks quickly and clearly, in an accent that can only exist in New York—Chernivtsi by way of Sheepshead Bay, containing textures of sharpness and emphasis originating on opposite sides of the planet. The first Republican to represent anywhere in Brooklyn in the City Council since 2002 speaks with a directness that may very well be native to southwestern Ukraine, but which anyone who rides the Q, F, or D trains far enough can instantly recognize.

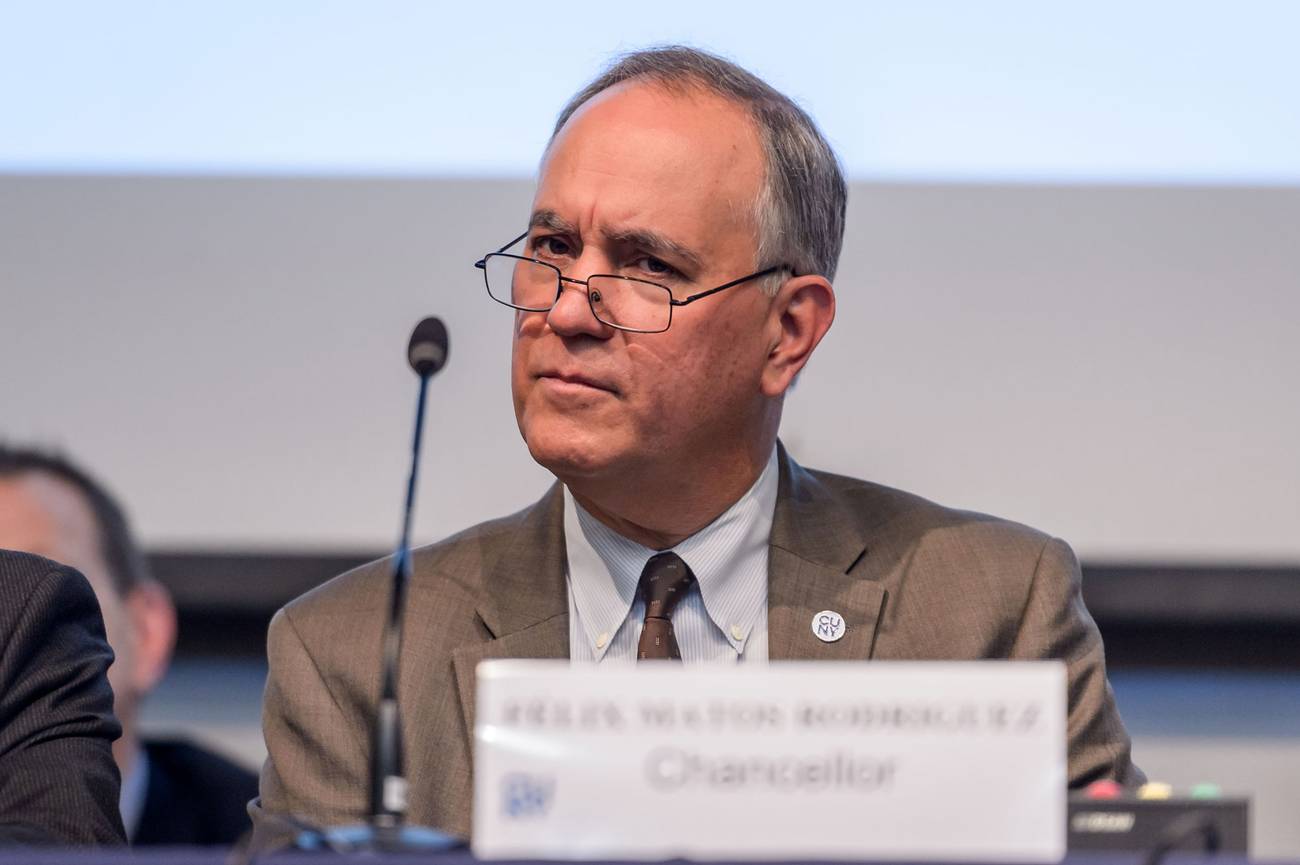

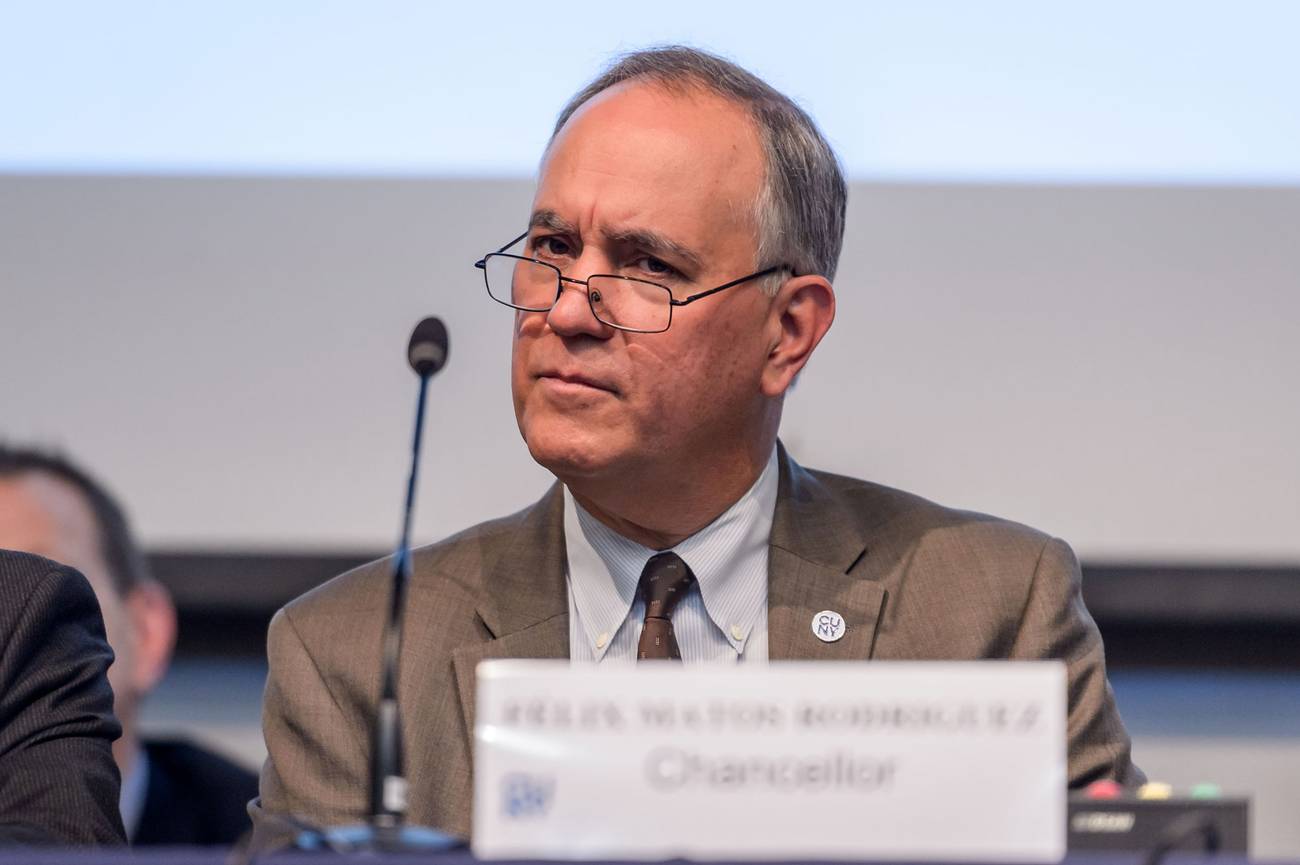

Vernikov explained that the morning’s hearing had originally been scheduled for early June, only to be canceled when CUNY Chancellor Felix V. Matos Rodriguez said he couldn’t attend. The meeting was postponed to accommodate him. In a rhetorical gift to Vernikov, Rodriguez decided at the last second that he wouldn’t show up today either. “What a sham,” thundered the councilwoman. “What an insult to the Jewish community of New York … This is why we have this problem, because nobody’s being held accountable.”

The accountability portion of the morning, a hearing of the City Council’s higher education committee, could be witnessed by only a small handful of people, thanks to ongoing COVID restrictions in municipal buildings, which are a convenient yet increasingly transparent excuse for the kind of open-ended petty dysfunction that characterizes much of life in New York now. The hearing took place on the 16th floor of a dispiriting ziggurat-shaped high-rise across the street from City Hall, and a line of scheduled witnesses was kept standing in its sweltering lobby for 45 minutes. Among them were Alyza Lewin, president of the Louis D. Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law, fresh off the organization’s victory against Unilever, which the day before had announced it was effectively overruling its subsidiary company Ben & Jerry’s boycott of Israeli communities in the West Bank. CUNY’s law school had become an area of particular focus for Lewin, who said that student and faculty BDS resolutions, along with the Kiswani speech, were part of a larger atmosphere of intimidation that had made most Jewish students afraid to assert their identities in any meaningful way. “It’s as if they’ve cleansed the law school of any pro-Israel or Zionist student,” she said.

How, I wondered, had CUNY become like this? What was it about the politics of the institution, or the politics of the famously Jewish city that operated it, that had allowed the university to reach this point? David Brodsky, chair of the Jewish studies department at CUNY’s Brooklyn College and a fellow line-stander, was meticulously nonpartisan in his analysis. The problem is much bigger than CUNY: “Antisemitism is systemic in Western society. It manifests in ways that are under people’s radar,” the Talmudist explained. “Unless you recognize where it’s coming from systemically, you fall prey to it.”

In Brodsky’s view, many of his colleagues had succumbed to this hidden and ancient mania, endemic to even the most tolerant and open of societies. He quoted an email from the Cross-CUNY Working Group on Racism and Colonialism addressing the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: “There are not multiple perspectives on this topic. There is only resistance or complicity to genocide.” Later, during his testimony before the committee, Brodsky mentioned an incident in which a professor withheld a recommendation letter until a student clarified their position on Israel, the kind of event that only needs to happen once to cause a broader chilling effect, as indeed it had. Jews have “an increasing fear of coming to campus,” Brodsky told the committee.

As I spoke with Lewin and Brodsky, Vernikov herself appeared in the lobby to personally assure everyone that they would have a chance to testify, and said she had asked for more people to be allowed into the hearing room. A few minutes later, the sergeant-at-arms announced that an overflow room had been set up just down the hall from the hearing. “She has a lot of ideas, which is good,” Karen Lichtbraun, a Manhattan activist with the more hardline Jewish group Yad Yamin, told me at the press conference earlier. “And she acts on her ideas, which most elected officials don’t.”

It turned out that the hearing was more compelling as a television show—with quick cuts between determined questioners and witnesses calling in from somewhere almost disrespectfully close by—than it would have been as a live event. Glenda Grace, a Columbia Law-educated special counsel to the university, was there in place of Rodriguez and appeared over Zoom. Vernikov earned her JD from the Florida Coastal School of Law, and she approached Grace as a cross-examining lawyer would, attempting to establish a series of premises that built off of one another. In turn, Grace’s goal was to avoid putting herself in the position of freelancing university policy by accident or admitting any legally actionable wrongdoing.

Vernikov sought to get Grace to affirm that Zionism was a core aspect of Jewish identity, such that attacks on Zionists as a group would then be considered discriminatory against Jews—meaning that CUNY would have a legal obligation to in some way lessen the impact of these attacks or stop them altogether. “I would have to look to see what our policy says,” was Grace’s consistent, lawyerly refrain, which carefully avoided turning Zionist Jews into a distinct identity group within the CUNY system. “I don’t understand what that means,” Democratic City Council member Kalman Yeger, himself an alumnus of Brooklyn Law School, eventually replied to the umpteenth reference to this suddenly ambiguous “policy.” “I think the word ‘dialogue’ was used several hundred times today,” Yeger later quipped to the committee.

At one point, Vernikov made three attempts at asking: “Do you think Jews can freely express their views on a campus where faculty open discriminate against them?” a question that Grace skillfully filibustered.

Rodriguez’s decision not to testify was a boon to CUNY’s critics, probably more important than anything actually said in the hearing. In the hearing room, the rhetorical deadlock often favored Vernikov, who understood that Grace was there in order to prevent CUNY from committing itself to much of anything. Vernikov asked if the school would denounce the BDS movement, in full knowledge of what the answer would be. Grace claimed that the university had already voiced its opposition to the boycott movement, and was prohibited by a state executive order to join a boycott of Israel even if it supported such a thing, which, to be clear, it did not. Grace even went so far as to say the movement was “wrong.” The word “denounce” was still nowhere to be heard, whatever the subjective importance of a CUNY official saying or not saying it. Later in the day, Vernikov would land a more definitive punch on CUNY union President James Davis, who under the councilwoman’s questioning either temporarily forgot that he was a supporter of BDS or was too ashamed to admit his actual views, even over Zoom.

Perhaps the goal of the hearing was a legalistic demonstration that CUNY and its faculty do not consider a supposedly core aspect of Jewish identity, namely Zionism, to be worth protecting on its campus, thus building a case for some future policy or reform. Yeger and Vernikov attempted to establish, with uneven success, that the administration’s alleged tolerance of organized faculty BDS activity amounted to discrimination on CUNY’s part, on the grounds that the school had allowed a hateful movement to fester among its staff and students. Grace, and thus CUNY, did not share Vernikov’s and Yeger’s apparent views on where the institution should draw the line between protected speech and alleged discrimination. The councilmembers nevertheless proved that no CUNY campus had any serious anti-antisemitism “sensitivity training” mandated among students or staff, and that antisemitism is at best an afterthought in the university’s otherwise formidable Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) regime.

One hearing witness was Adela Cojab Moadeb, who has no CUNY affiliation but recently sued New York University, alleging that a failure to prevent the mistreatment of Jewish students amounted to a violation of her rights under Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Title VI mandated that “students have to have equal access to educational opportunities” in accordance with their “full identity,” Lewin had explained to me downstairs while we both waited in line. In essence, Lewin said, universities have “a legal obligation to protect students from harassment.” If they can’t meet that obligation, they’ve jeopardized their various accreditations and could become ineligible for government funding.

It is not a stretch to wonder if a pro-Zionist diversity bureaucrat is an ideological contradiction in terms.

The threat of lawsuits or the prospect of other Title VI-related enforcement could force the university into action. What kind of action? Vernikov’s prescription included sensitivity training around antisemitism, the appointment of a diversity officer who would handle cases of antisemitism, and CUNY’s adoption of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition of antisemitism, which has been widely interpreted as claiming that anti-Zionism can be a type of anti-Jewish hatred.

The critics’ strategy seems to be to use both the legal system and legislative pressure to force CUNY to more fully include Jews within its existing diversity bureaucracy. This means accepting the divisive logic of this bureaucracy, which would turn Jews into another one of a range of aggrieved and oppressed campus minority groups, complete with their own designated institutional protectors who can supposedly ensure that they are treated with the level of respect that federal civil rights law and the university’s nondiscrimination policy require. This approach comes with its own complications and contradictions. Perhaps it is the sensitivity-training industrial complex that itself creates the current hierarchy of bureaucratic concern, for example, allowing for fashionable bigotries like antisemitism and Israelophobia to fester and bloom while focusing its efforts on what are deemed to be more urgent manifestations of America’s incurable racism.

It is not a stretch to wonder if a pro-Zionist diversity bureaucrat is an ideological contradiction in terms, and if on a present-day campus, the antisemitism-focused officers will themselves be anti-Zionists empowered to define any pesky-enough problem out of existence. In the unlikely event the bureaucrats are in fact Zionists, they might be just as isolated and scorned by their colleagues as many Jews at CUNY apparently are these days.

Perhaps DEI just doesn’t work and training college students, faculty, and administrators to be more sensitive to Jews—and also to fear Jewish students’ hypothetical ability to wreck their lives and careers—won’t have the harmonizing outcome Vernikov and others hope it will. But perhaps there’s no other way now, and at an institution like CUNY, a group must either work within a morally and legally corrosive system with no proven record of solving the problems it claims to exist to solve, or risk having no protections left at all.

Armin Rosen is a staff writer for Tablet Magazine.