Democracy and Its Tens and Twenties

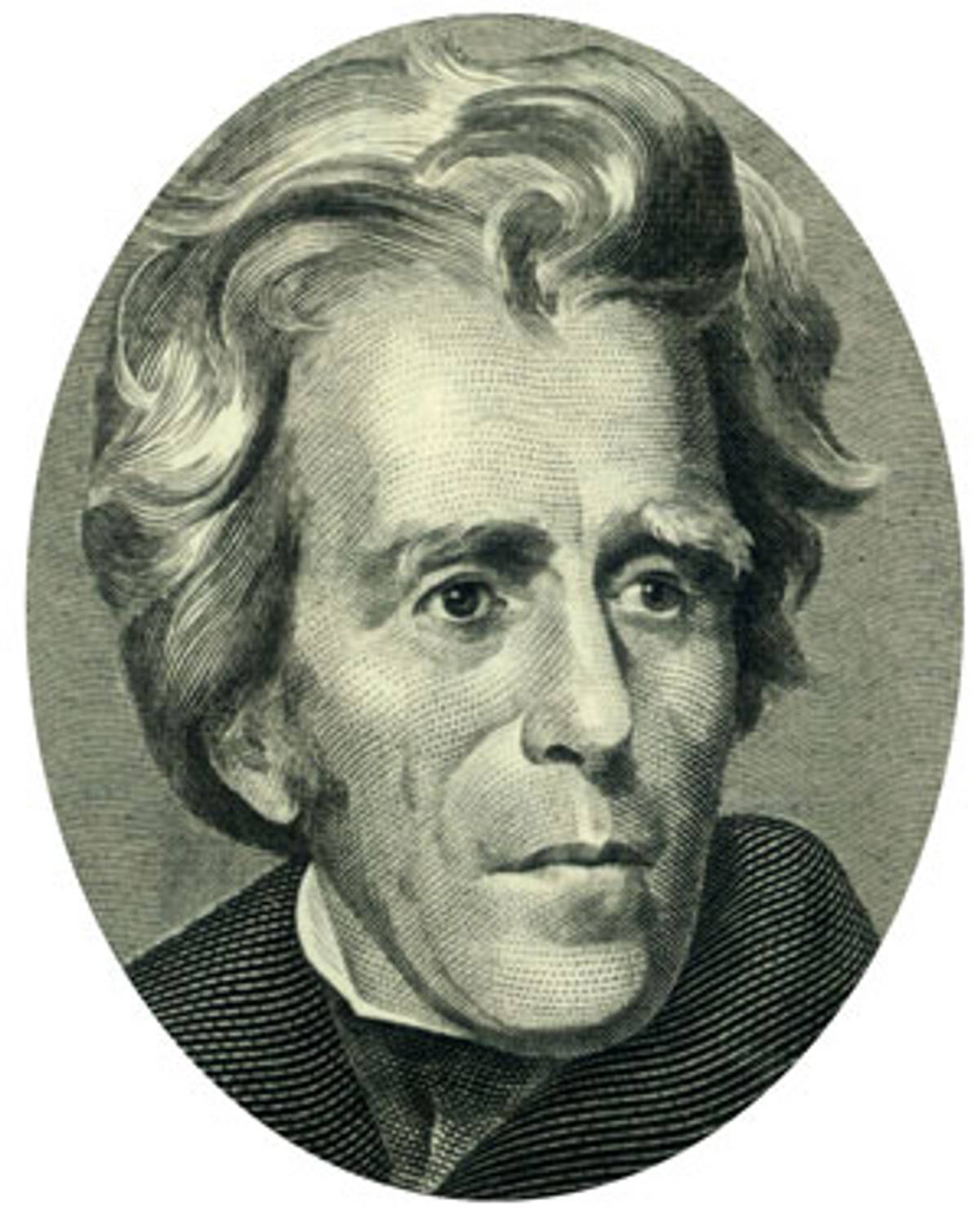

Do not remove Andrew Jackson’s face from the $20 bill. It reminds us that democracy has always been a struggle against aristocracy and special privilege.

Steven Rattner, the economist, has made the case—echoed by Ben Bernanke, no less—that, in regard to the $10 bill, Alexander Hamilton should stay (and he does seem to be staying, though he will share the space with a woman). And, in regard to the $20 bill, Andrew Jackson should go. Hamilton should stay because, back in the 1790s when he was treasury secretary, he was right about all the economic issues. He was right about the dollar; right about the need to pay off the colonial debts; and right about the useful role the federal government could play in promoting industry in waterfall towns like Paterson, New Jersey. And Jackson should go because, on the economic questions of the 1820s and ’30s, he was wrong. Jackson was wrong to oppose paper money and wrong to veto America’s central bank, the Bank of the United States. In Rattner’s interpretation, Jackson’s bank veto made it harder to fend off the financial crash of 1837. And the bank veto left a hole in the national financial system that lasted until 1913, when the Federal Reserve was finally established. Such is the argument. It convinces me that economists should never have the last word.

Jackson is not on the $20 bill because of his economic sophistication. Jackson is on the bill because he was the symbol and sometimes the leader of the first and most important mass democratic movement in American history—the movement that set the pattern for all subsequent mass movements that have powerfully advanced the democratic cause. The United States that came out of the American Revolution retained some of the traits of European feudalism—a concentration of wealth and might in the hands of tiny aristocratic elites; a lingering political power for the Presbyterian and Congregationalist churches; a habit of deference on the part of everyone else, the humble masses. By the 1820s the aristocratic features, instead of fading into the past, seemed to be taking on new features with the rise of industrial capitalism, which created spectacular new fortunes for the privileged handful. And the new system, through its banks (and their paper money), imposed monopolies and inhibited competition, which, at least in some people’s view, made it still harder for the ordinary masses to go into business on their own or even to maintain traditional living standards.

And so, people objected. Movements arose to expand voting rights to all white men, regardless of their poverty, which was a big change; and to expand the right to vote and to hold office even for people outside the mainline Protestant denominations, which meant Catholics especially (and even Jews, of whom there were not too many, but their rights did get discussed). Artisan and labor movements put up a fight against the 11-hour work day (imagine!) and other cruelties of the new industrial age. There was a movement of politicos who called themselves “Equal Rights Democrats,” otherwise known as Loco Focos, who explicitly postulated an egalitarian democracy as the key to a new civilization. And behind these many campaigns and others still more radical was the growth of something vaguer, a culture of democratic impudence, which challenged the old-fashioned habit of obedience to the aristocrats of the past and present.

Jackson and his ally Martin Van Buren and their fellow politicos and journalists succeeded in drawing together those many movements and impulses into an electoral coalition, which became the first solidly footed mass national political party anywhere in the world. This was the Democratic Party—a party with roots reaching back to Thomas Jefferson and his anti-Hamiltonians but that took on a modern shape and its modern name only under Jackson and Van Buren. And, in 1828, Jackson’s Democrats won the national election—won on the basis of a larger electorate and larger turnout and many more humble people than in any previous election in all of history.

Andrew Jackson is on the $20 bill because he was the symbol and sometimes the leader of the first and most important mass democratic movement in American history.

An ebullient mob tramped through the White House on the occasion of Jackson’s inauguration in 1829 because everyone knew that his victory was a turning point in world events. It was the circumstance that converted the American Revolution of 1776 into a democratic revolution—a revolution that did not pretend to have created perfection but was visibly successful at establishing a newly egalitarian political culture, not among everyone but in the mainstream of society. And the Democratic Party under Jackson became a party that, at least sometimes, favored (in the language and the italics of the 1830s) labor over capital.

Jackson’s veto of the Bank of the United States? Steven Rattner (who ran President Obama’s successful bailout of the auto industry) and Ben Bernanke (who ran the Federal Reserve’s equally successful policy to recover from the crisis of 2008) should draw a sober lesson from this. Rattner and Bernanke are right to suppose that, in the 1830s and afterward, the United States stood in need of a central bank. But the Bank of the United States represented economic power in an unacceptable form. The Bank of the United States was not the people’s bank. It enjoyed the special privileges of a national central bank and yet was privately owned chiefly by 4,000 stock holders. Economically the bank might have been a good idea. But politically it was not appropriate for a democracy. It was monopoly incarnate. It was the royal institution of the new financial aristocracy that posed a danger to America’s political development. So Jackson abolished it. He ought to have replaced it with something else, but, anyway, he got rid of it.

Sean Wilentz’s magisterial history of the early United States, The Rise of American Democracy, quotes Jackson’s statement about vetoing the bank:

Distinctions in society will always exist under every just government. Equality of talents, of education, or of wealth cannot be produced by human institutions. In the full enjoyment of the gifts of Heaven and the fruits of superior industry, economy, and virtue, every man is equally entitled to protection by law; but when the laws undertake to add to these natural and just advantages artificial distinctions, to grant titles, gratuities, and exclusive privileges, to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of society—the farmers, mechanics, and laborers—who have neither the time nor the means of securing like favors to themselves, have a right to complain of the injustice of their Government.

That is why Jackson is on the $20 bill. It is because of that phrase about “the humble members of society.”

Oh, and am I right to say that Jackson’s victory was a turning point in world events? I refer you to Stendhal’s novel Lucien Leuwen, from 1830, about young Lucien, who gets expelled from school because of his activity in a left-wing faction. Lucien joins the army and gets posted to a provincial town somewhere in France, where he befriends the editor of the local red socialist newspaper, whose hero, the leader of the world left, is—this is the surprise—Andrew Jackson!

***

Rattner makes two undeniable anti-Jackson points that have the merit of being non-economic, namely, that Jackson presided over an appalling policy of Indian removal in the South. And Jackson owned slaves. How barbarous were America’s early decades! Jackson was a savage even in his body aches. He entered the White House carrying in his chest a bullet from a long-ago duel (in which he coldly murdered the other man) and in his shoulder a bullet from a gunfight, which had to be removed. In Jackson’s defense nothing can be said, not in regard to Indian removal and African-American slavery. And yet something can be said about his movement, or what was called Jacksonian Democracy.

The Jacksonian Democrats were not, as a movement, the enemies of Cherokees, Choctaws, Creeks, Chickasaws, and Chief Black Hawk and his tribes. Some of Jackson’s followers supported the Indian removal policy, others opposed it; and they remained Jacksonians, either way. Likewise with slavery. Jackson as president was a middle-of-the-roader (in the deplorable context of the time) on the controversies over slavery. His vice president during his first term was John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who was the political theoretician of the slave South. But Jackson turned against Calhoun and, for the second term, replaced him with Van Buren—who evolved from being a cynical conciliator of Southern slave-owners to being their enemy. Van Buren by 1848: Walt Whitman’s candidate on the anti-slavery Free Soil ticket. There were radical Jacksonians who promoted militant abolitionism, a New York faction. Maybe these details of political history mean only that, in the decades before the Civil War, the American South was trapped in its dreadful tragedy, and the North less so. Jacksonians of the South marched insanely toward their Confederate doom; and Jacksonians of the North veered unsteadily in better directions. And the movement’s ultimate legacy, being ambiguous on these matters, is up to us to decide.

Should we resolve the ambiguity by removing Jackson from the $20 bill? I think that Jackson’s horsey face and streaked mane on the bill should remind us, instead, that democracy has always been a double struggle. Democracy is a struggle against aristocracy and special privilege. Jackson is a symbol of this particular struggle, among the great majority of the American population. And democracy is a struggle against mad bigotries and anti-minority persecutions. This second struggle will have to be symbolized by someone other than Andrew Jackson—an honor to be conferred on some other bill, or on several bills.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.