DIY Judaism

‘The Jewish Catalog’—a quasi-hip, countercultural book of how-to Judaism—was all the rage in the Seventies. How does it hold up now?

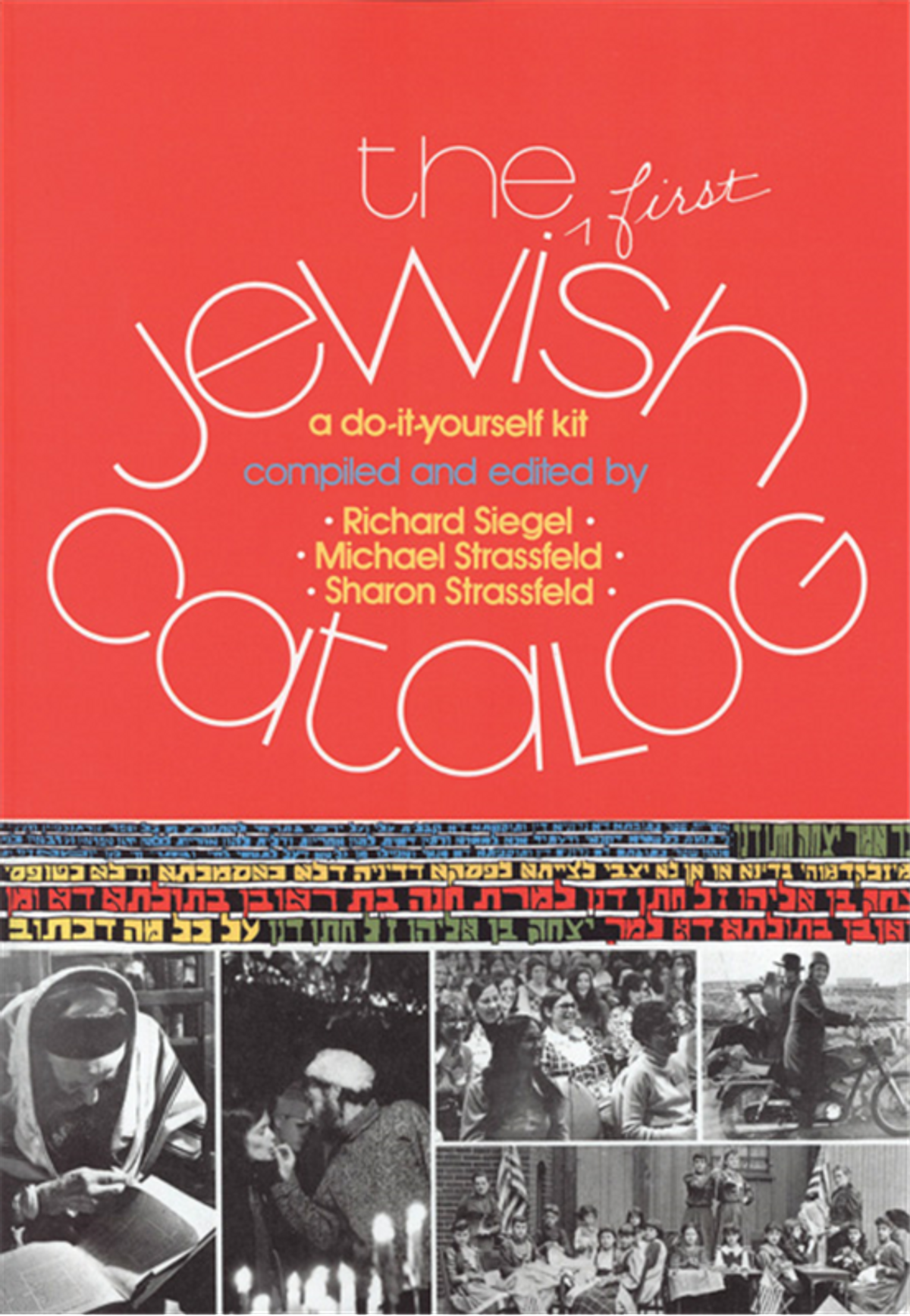

Oh, 1971—what a grand-time for hand-lettered, oversized do-it-yourself catalogues! Eco-theorist Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog was first published in 1968 but reached the zenith of its influence in 1971, when a new edition, expanded to 452 pages, ran on its cover the great Apollo 4 photograph of the Earth as seen from space. In 1971 the Boston Women’s Health Collective published the first edition of Our Bodies Ourselves, the pioneering gyno-manual that treated the female orgasm, masturbation, lesbianism, and zaftig body types as natural variations rather than oddities, sins, or imperfections. And three members of Havurat Shalom, the still-extant havurah-in-a-house in Somerville, Mass., began writing The Jewish Catalog, the first edition of which was published, in all its black-and-white, photo-and-illo-spotted glory two years later.

If you haven’t seen The Jewish Catalog, do, now. The book that does it all, offering sensible peer-to-peer advice, just enough halakhic wisdom (you’ll find no better synopsis of the kosher laws), and the best diagram for wrapping tefillin that was ever rendered by your friend in Hebrew school who was always sketching things under his desk. The best pictures look like Shel Silverstein’s (I won’t die from surprise if someone writes in to say they were Shel Silverstein’s). It tells you how to build a sukkah, how to affix a mezuzah, which blessings to say over what, and how to get by when hitchhiking around Israel (“Get a haircut; Israelis are wary of foreign ‘hippies’”). It offers instructions for sitting shiva, and it tells you where in all the major American cities you can rent Jewish movies. It’s a panoramic view of a young idealist’s idea American Judaism, circa Laugh-In and Portnoy and Nixon. And it’s the kind of handbook that the internet was supposed to render useless, but which in fact the web has made more desirable than ever. (Jen Bleyer, founder of the late great Heeb, offered her own take on the catalog, for Tablet, 10 years ago.)

When twentysomethings Richard Siegel, and Michael and Sharon Strassfeld, began piecing together the catalog, they figured that young members of the Jewish counterculture, the kind who might have spiritual yearnings but deeply mistrusted the institutional synagogues in which they’d been raised, needed one-stop shopping for Jewish knowledge. What they came up with was perhaps less hip than what they’d intended but it was indeed more haimish—the wedding section tells people to ignore the “hassles of parents, relatives, and other people’s opinions” but also offers a Jewish White Pages of recommended wedding bands, including The Epstein Brothers (211 W. 53rd St, NY, NY) and one Shlomo Carlebach (15 E. 26th, and it gives his phone number, too). And the mimeograph-era typesetting and design—you’d pay a mint for it today and still the designer wouldn’t quite nail the sans serif.

“I think part of what the counterculture was about, and the Jewish counterculture specifically, was democratizing things,” said Michael Strassfeld, one of the catalog’s original editors, last week. “To open up access to lots of people, and move away from what was perceived as hierarchical. In the case of synagogues, services were run by the rabbi and the cantor, and often people in the pews were pretty passive, and I think that part of the what was in the air at the time, the 1960s, was this sense that things should change, be open to change, and that there’s a new generation that wants to do things in a different way. The subtitle was A Do It Yourself Kit.”

Strassfeld, who retired in 2015 as the rabbi of the Society for the Advancement of Judaism, in Manhattan, said that if you include the second and third editions (1976 and 1980), the catalog has sold about half a million copies. What’s more, it was read across most of the spectrum of American Judaism; despite its liberal vibe, it was even reviewed in Orthodox publications, something that Strassfeld points out would not happen today.

“It’s a little chutzpahdik to say this,” Strassfeld said, “but I think it really had a fairly large impact. A number of years earlier it might not have gotten any attention, and a number of years later it might not have felt so different or groundbreaking.” While there were a lot of books being written about American Judaism—aren’t there always?—there was nothing like this, that treated practical skills like cooking alongside tefilla, prayer, treating them all as components of an integrated Jewish life. “It was a catalog—if you want to tie tzitzit, here’s how to do it.” And yet it wasn’t prescriptive, at least not obnoxiously so. “It didn’t imply that to be a Jew you had to keep kosher, observe Shabbat, etc., etc. What the catalog really was about was sharing our Jewish lives with people, saying, ‘We are doing this, we enjoy this, we think you might.’”

Of course, all the information the catalog gives is now available online, in a multitude of places. To learn how to pray, you can find Reform sources, Conservative sources, a dozen flavors of Orthodox sources. You can find melodies by dozens of composers, you can put “Jewish” in the search-bar of your video streaming services, you can visit a website that tells you what drinks are kosher at Starbucks. But in diversity, we sometimes wish for unity. The Jewish Catalog is one of those books, like Irving Howe’s World of Our Fathers, or Herman Wouk’s Marjorie Morningstar, that you could spot on the bookshelf of a certain kind of Jew and just nod, slowly, and give a look that says, “Yeah.”

What book does that today? Now as then, there are some novels that might pass the test, but they don’t imply any attitude toward Jewish living, any disposition to figuring it out and keeping on keeping on, the way The Jewish Catalog did, and does. We need The Jewish Catalog the way we need womyn’s bookstores and gay bars. Your patronage is a badge of identity, one you wear or perform or shout out loud. You can’t dive into people’s search bars and check out what they looked up at MyJewishLearning.com or Chabad.org. But you see a Jewish Catalog on their bookshelf.

And you can take it down, and open it up, and read in it that “L’Kha Dodi” can be set to Simon and Garfunkel’s “Scarborough Fair.” And you can learn how to blow a shofar. And you can read a quotation from T.S. Eliot, in a chapter on the mikveh. And you can learn gematria. And you … you … can!

Related: Do It Yourself

Mark Oppenheimer is a Senior Editor at Tablet. He hosts the podcast Unorthodox. He has contributed to Slate and Mother Jones, among many other publications. He is the author, most recently, of Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood. He will be hosting a discussion forum about this article on his newsletter, where you can subscribe for free and submit comments.