A Holocaust Hero in the Congo

David Sompolinsky saved hundreds of Danish Jews from the Nazis. Then he went to Africa.

“According to the newspaper and the radio, the Congo is now the epicenter of global unrest, a powder keg. And here I am some 30 days in the Congo. The land is quiet, pleasant, smiling.”

Sometime in the summer of 1960, Dr. David Sompolinsky—an ultra-Orthodox Jew throughout his long life—scribbled these words onto Air France stationery, part of a 12-page handwritten report on his time in the fledgling African nation.

Nearly two decades had passed since Sompolinsky had risked his life in a very different environment, working valiantly to save hundreds of fellow Danish Jews from the Nazis.

In his book October ‘43, devout Christian Danish resistance fighter Aage Bertelsen—who worked closely with Sompolinsky rescuing Danish Jews—recalled David’s vast knowledge of Halacha, which he kept “conscientiously and rigidly … even more than other orthodox Jews,” as well as his striking, selfless courage:

Incessantly, day and night, literally, David was busy helping, completely disregarding his own dangerous situation … He was on the go everywhere, and everywhere he looked up Jews and helped them out, always bubbling with activity, yet always well balanced, cheerful, but also cunning and level-headed.

After the war, David returned to Denmark, where he finished his studies prior to moving to Israel in 1951.

It was in his new home that he would soon become a respected expert in microbiology and take part in an epic mission to Africa.

In the summer of 1960 there were two newly established neighboring countries, both known as “The Republic of the Congo.” To avoid confusion, the Belgian Congo was referred to as “Congo-Léopoldville,” and the French Congo as “Congo-Brazzaville.”

Only 12 years old itself, Israel was still a developing country at the time. The Sompolinsky family, like many others, did not even have a refrigerator in their home.

Nevertheless, the young state—driven by Jewish humanitarian values and practical diplomatic concerns—dispatched numerous foreign-aid missions in those early years.

Israel had, in fact, boasted one of the largest delegations at Congo-Léopoldville’s official independence festivities on June 30, 1960, which included then-Minister of Finance Levi Eshkol.

Sompolinsky was asked to join an Israeli delegation being sent to help set up the nascent country’s medical system.

Headlines from Léopoldville were troubling. Violence and chaos appeared prevalent.

Rumors reached Sompolinsky’s wife, an Auschwitz survivor with nine children under the age of 14 at home, that cannibals were prevalent in the Congo.

And yet David, who had risked his life saving the Jews of Denmark, felt obligated to use his professional expertise to help those in need and fulfill what he saw as his Zionistic civic duty.

And so, one day in July 1960, Mrs. Sompolinsky took her nine small children along to Lod Airport to bid farewell to their father, and he was off to Africa.

The Israelis nearly didn’t make it to their destination. After stopping in neighboring French Congo, the team was informed that it wouldn’t be able to get to Léopoldville because the situation was too unstable.

Determined nonetheless to begin their mission as soon as possible, they managed to score rides on two small planes and a helicopter, eventually reaching their destination on July 24, 1960.

What the Israelis found in the Congo surprised them: in some ways better than what they anticipated, and in some ways much worse.

In an interview published in the Ma’ariv newspaper shortly after Sompolinsky returned to Israel, he even used the word “holocaust” to describe the medical situation they encountered when they arrived:

When the Belgians were in the Congo, there were 800 doctors and 50 veterinarians. Now, almost all of them have left the country. Medically this is a holocaust, and yet the Congolese believe that they can overcome anything as long as they are their own masters.

Many of the estimated 200 hospitals and 80,000 beds were inaccessible due to violence, instability, and other factors.

The situation they found was a bizarre paradox of sorts, as the former colony was actually exceedingly well-equipped in some respects, especially compared to Israel at the time.

Preventative medicine in the Congo is incomparably more developed than in Israel. … They have equipment that we in Israel don’t even dream of.

“Preventative medicine in the Congo is incomparably more developed than in Israel. … They have equipment that we in Israel don’t even dream of,” Sompolinsky assessed, recalling one of the hospitals in Léopoldville as “massive,” with an exceptional institute for tropical medicine unlike anything in Israel.

With the indigenous population barred from many areas of higher education and training under the oppressive Belgian colonial system, the young country suffered from a gaping vacuum in terms of personnel to operate key areas of the medical system.

When he got there, for example, Sompolinsky found that some locals knew how to perform various lab tests but had never been trained in analyzing the results, rendering their efforts all but pointless. By the time he and his team left, the Congolese could run the labs and analyze test results completely independently.

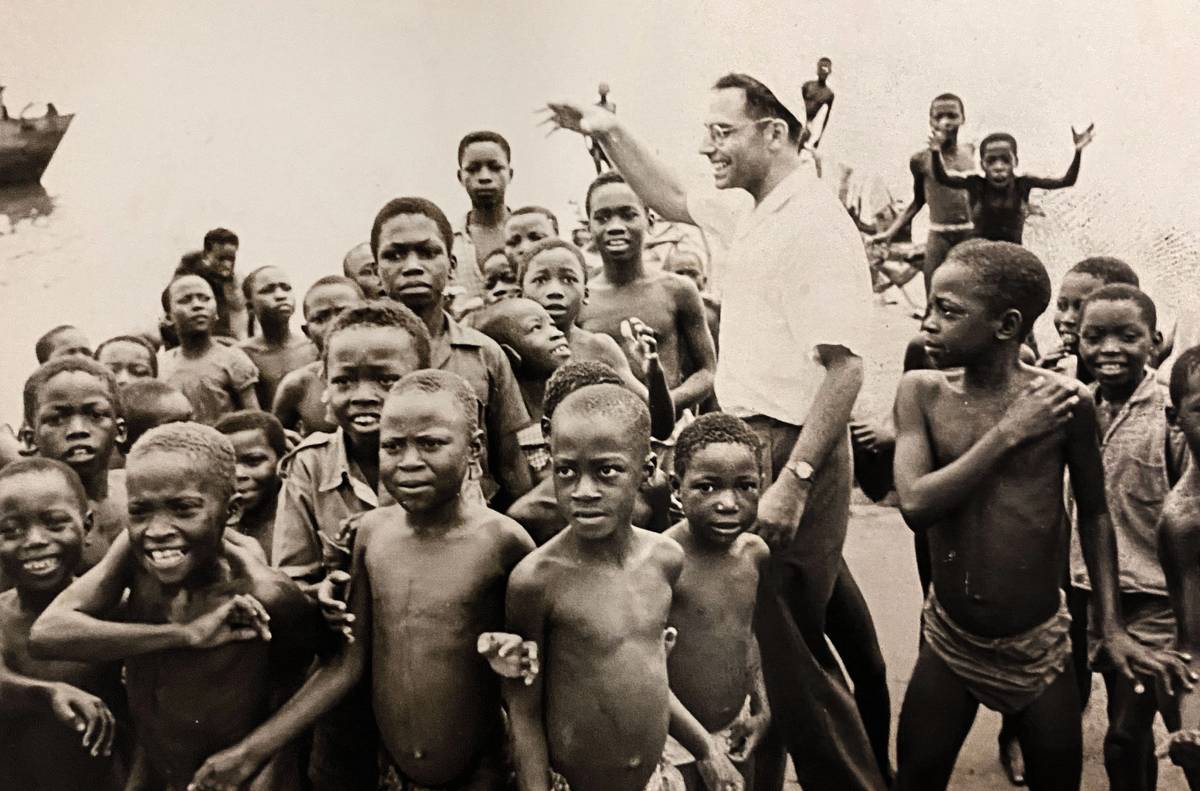

“The Congolese are a marvelous people, warm and full of faith in the future,” Sompolinsky would later report.

He and his team had indeed been warmly welcomed. They encountered no cannibals and did not feel particularly threatened as “white” people, which they thought they might. Locals clarified that it was only the Belgians they hated.

White U.N. soldiers were actually a common sight in the streets of Léopoldville: The young doctor recalled shocking some Swedish U.N. personnel when—speaking fluently in their native tongue—he explained what the Israelis were doing in Africa and told them all about life in Israel.

As far as the locals were concerned, Jerusalem and Nazareth were familiar from the Holy Bible, not from any contemporary atlas. Sompolinsky and his colleagues, sporting the symbol of the Jewish state, were in many cases the first to ever inform many of those they encountered that the State of Israel existed.

Walking to fulfill his medical mission one Shabbat (when driving is forbidden according to Jewish law), Sompolinsky was stopped by a group of Congolese soldiers “hunting” for whites, according to the Ma’ariv article:

At first he was stuck in a quandary, but ultimately decided to act as naturally as possible. He approached the Congolese officer and said 'mbote' to him, meaning ‘hello’. This greeting was enough: Within one minute Dr. Sompolinsky found himself surrounded by Congolese soldiers listening with intent and curiosity to the reason the Israeli delegation had come.

Though already in 1960 there were some Israelis and other Jews living in the Congo, Sompolinsky was unable to form them into a minyan, even on Shabbat.

Never one to compromise his kashrut standards, Sompolinsky survived largely on papaya and other fruits.

Yet his physical distance from the “comforts” of Jewish communal life and his children did not stop him from working to fulfill the commandment to educate them, as evidenced in the postcards he frequently sent back to his family. He would drop them at the Israeli Embassy simply addressed to: “Mademoiselle Sompolinsky, Rishon Lezion.”

In the letters, he provides details of his daily life in the Congo, while also clearly trying to model and educate his children from afar.

In one, he describes seeing traditional African face scarring, and goes on to explain to his children how the practice is forbidden according to Jewish law.

On the solemn day of Tisha B’Av, he wrote how his fast had gone quite easily and that in the afternoon he would put on his tallit and tefillin, in accordance with Ashkenazic Jewish tradition.

In the same letter, he chronicles some of the many injustices the local Black population had to bear under Belgian rule, his tone clearly reflecting the deep impact that seeing such racism had on him, a devout Jew who narrowly escaped the Nazi genocide.

The only Black person allowed on white buses was the driver.

Bathrooms and kitchens were segregated, with Blacks given far inferior facilities.

Black people who wanted to use the telephone had to submit a special request, including the reason for the call and the name of the intended recipient.

Blacks were expected to greet and bow to any whites they encountered, without ever expecting even the most basic acknowledgment of their existence in return.

In this context, Sompolinsky clearly took pride in the role he was able to play in helping the new masters of the Congo set up a functional medical system following centuries of colonial rule and oppression:

“I have no doubt, and I am happy and proud that our mission is spreading the idea of loving one another, loving humanity, without paying attention to skin color.”

In the letters, he told his wife and kids how much he missed them and beckoned the children not to fight with one another or with their mother. When he came back to Israel, he brought exotic gifts including detoxined poison arrows, with which generations of Sompolinsky children would play.

Sompolinsky helped start a program to bring Congolese fellows for training at Bar Ilan University, and over the next six decades he would become a prominent figure in the field of microbiology, playing an active role as Israel became a global leader in medical research and practice.

He even launched a few public health crusades of his own, including one to warn his local ultra-Orthodox community about the fatal dangers of smoking.

David Sompolinsky continued working well into his 90s. He passed away in October 2021 at the age of 100.

An extensive obituary appearing on the leading ultra-Orthodox news site B’hadrei Hadarim eulogized Sompolinsky as not only a savior of Danish Jewry and a founding father of Israel’s scientific community, but also as a genius “immersed in the world of Torah, a tremendous scholar who never spoke idle chatter” and who had special relationships with some of the 20th century’s most prominent rabbis, including the Hazon Ish and the Brisker Rov.

Perhaps reflecting hopes for his own children at the time, Sompolinsky had concluded his 1960 report with his belief in “a happy and prosperous future for the Congolese people,” whose youth were “courageous and knowledge-seeking.”

The mission to the Congo was a biographical drop in Sompolinsky’s centurylong story, but a tale that was known to many of his estimated 700 living descendants, and one that undoubtedly reflected a man with seemingly boundless dedication to bettering the human experience and remaining full of faith in the future.

Zack Rothbart is a writer, editor, and international spokesman at the National Library of Israel, where he manages global content and media relations and co-edits The Librarians, an online publication dedicated to Jewish, Israeli, and Middle Eastern history, heritage and culture.