Jewish Giants of the NFL

In an excerpt from ‘Eat My Schwartz,’ the first pair of Jewish brothers to play in the NFL since 1923 talk about Jewish stereotypes, appreciating Passover, and their addiction to latkes

Mitch

Neither of us realized it at the time, but my arrival in the league was a historic event for ethnographically inclined students of the game. I don’t know who researched the matter, but before I had even played my first game, someone decided to find out how many Jewish brothers had played together in the NFL. It turns out Geoff and I were the first fraternal “members of the tribe” to roam the fields of the NFL since Ralph and Arnold Horween played in 1923.

I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised that someone would research this. Growing up, as huge sports fans and as Jews, we were definitely aware of the few professional athletes who were Jewish. It was just common knowledge. Something you discover about a player because . . . well, there just aren’t that many of us in the world of professional sports. According to the U.S. Census, Jews make up about 2.2 percent of the U.S. population. Assuming that metric is accurate, Jews as a demographic group are underrepresented in pro sports. That fact leads to a joke every Jewish kid knows: What’s the shortest book ever written? Jewish Sports Legends.

I think it’s good to be able to laugh at myself. Of course, there have been some truly great Jewish athletes: Hank Greenberg and Al Rosen were former MVPs in baseball, and Sandy Koufax may have been the most dominant pitcher in the history of the game. In swimming, Mark Spitz, Jason Lezak, and Dara Torres brought home plenty of Olympic gold medals. In boxing, we were represented by two well-known sweet scientists: Max Baer, the former heavyweight world champ, and Barney Ross, who held three belts in lighter divisions. In basketball, Dolph Schayes was a major force in the ’50s, along with Red Holzman, who went on to be a legendary coach of the New York Knicks.

Growing up in L.A., I knew about Sandy Koufax, and everyone in town knew Shawn Green of the L.A. Dodgers was a member of the tribe. But I had no idea about the history of Jews and football.

It turns out that Ralph and Arnold Horween were major football stars. They were All-Americans at Harvard, where they starred in the backfield. They joined the Racine Cardinals of the fledgling Canton, Ohio-based American Professional Football Association and moved with the team when it became the Chicago Cardinals. Interestingly, they played using an Irish last name, McMahon. It is not clear to me exactly why they used an alias. I’ve read one theory that they wanted to protect the family name. But since the family name had been changed from Horowitz when they first arrived in the United States, you have to wonder what was going on there. Was football looked down upon? Was their family ashamed? Or were they concerned about anti-Semitism? I’m not sure what the motive was. The name game gets even stranger when you read the obituary notice for Ralph that ran in the Chicago Tribune—it mentions that Ralph was the first NFL player to live to be over one hundred years old— and discover that Ralph’s two sons have the last name Stow. Were they his stepsons? That’s another mystery.

As a guy who majored in American Studies, I had fun looking the Horweens up. They sound like great guys. They both withdrew from Harvard during World War I and enlisted in the Navy. Then they came back, finished school, won the Rose Bowl, and turned pro. Eventually, Ralph went to Harvard Law School and became a patent lawyer, while Arnold ran the family business, the Horween Leather Co. And guess what: Their leather was used to make footballs for the fledgling league.

It was also cool to discover that Jews were no strangers to the NFL in the early days of the league. Many Jews were stars during the 1930s and ’40s, and none was bigger than Chicago Bears legendary quarterback and Hall of Famer Sid Luckman. In the modern era, I think Lyle Alzado might rank as the most famous football player with a Jewish heritage. When Geoff came into the league, there were ten or eleven Jewish guys playing, but that number has dropped. Off the top of my head, I can think of Gabe Carimi, an offensive lineman for the Atlanta Falcons, Nate Ebner, a safety/ defensive back for the New England Patriots, and Taylor Mays, a special teams guy for the Oakland Raiders. Five guys out of 1,600 active players in the league? That’s about 0.3 percent. Numbers like that make me realize that Geoff and I are a rarity.

I don’t think I quite understood how important it is to some people that there are Jews who are professional athletes. I’m starting to realize how big a thing it is in general. It makes sense; all ethnic groups are proud of their members’ achievements. Geoff and I are members of an elite profession.

The first time it really hit me was when I drove to Canton, Ohio, to visit the Pro Football Hall of Fame one Friday. I had been in Cleveland a couple of weeks and I thought it would be cool to go check it out. Canton is only about a ninety-minute drive south of Cleveland. It was a great place to take in the history of what has become the most popular sport in America. When I came outside, there was a busload of Orthodox teenagers visiting from New York. Just like there are many denominations of Christians, there are all kinds of Jews. Orthodox Jews—and believe me, there are many different Orthodox sects—are extremely observant. The men keep their heads covered with yarmulkes or hats, and they pray numerous times a day. They believe that the Torah, or Old Testament, is God’s law along with the Talmud. I was surprised to see the group there at the Hall of Fame.

And they were surprised that there was such a thing as a Jewish football player. When someone pointed me out to them, they flocked over and peppered me with questions, asking if I played quarterback, if I would pose for pictures, and if I would sign autographs. It was really strange for me because I don’t usually think of myself as a big name or a celebrity. But suddenly, at least to these kids, I was.

“I’m going to root for you every game,” one kid told me. “Except when you play the Giants.”

Geoff

When Mitch arrived in the league, we instantly accounted for at least 20 percent of all Jewish players in the NFL, or probably more. As my brother said, there seems to be between five to ten players in the league at any time. I suppose there are more Jews than there are Hindus and Buddhists, but I guess our numbers in the league and across America are low enough that it turns out a lot of players don’t know much about the Jewish faith.

I enjoy sharing aspects of the culture I grew up with.

Coming from a Conservative Jewish family, I loved the traditions, the rituals, the lessons, and of course, the meals. They are totally part of me. I have been asked a lot of questions over the years. When I showed up in Oregon, one guy asked if my family celebrated Thanksgiving. I told him I was an American and that, yes, my family loves Thanksgiving, we celebrate it every year. I should have added that giving thanks is one of the things Jews do all the time in our prayers. Many Jews thank God for food and wine before meals, not unlike saying grace.

The other really common question people ask me is: “Do you get a present every night during Hanukah?” My answer is: “Yeah, I did when I was seven.” But the fact is, Hanukah isn’t the huge gift-giving event that Christmas is. Some families may treat it that way, but my family didn’t.

Questions like that don’t surprise me. If you’ve never come in contact with or studied a culture or religion, then how can you be expected to know much about it?

Still, ignorance and insensitivity can be shocking. During my second year at Oregon, a freshman performed a song during a rookie show that referenced “Jews burning in ovens.” I think that some people don’t really realize that the Holocaust is not something to joke about. Back then I was just disappointed that people can be so unaware and unfeeling.

Of course, that is nothing compared to the story a Jewish friend of mine once told me. He was living in upstate New York when a casual acquaintance asked if it was true “about the checks.”

“What are you talking about?” my friend asked.

“Do you really bury the dead with blank checks so they can buy their way into heaven?”

What do you say to something as ridiculous and nasty as that?

That kind of racist mythology and stereotyping is horrible and offensive. So I actively share the Jewish traditions I can with my teammates. During Hanukah, I’ve traveled with a menorah and lit candles in the hotel room, once with a coach who was Jewish. As you know, Mitch and I are latke addicts. But latkes, as I’ve said, are work-intensive food because of all the peeling and grating. Recently I found a great recipe that takes the work out of latkes, so I can make huge batches for my teammates. The secret is using pre-sliced frozen hash browns. I can hear latke fans out there groaning in protest. Hey, I was skeptical, too. But this is a low-intensity latke workout. You defrost the hash browns, squeeze out the liquid, grate the onion, squeeze out that liquid too, mix it all together with the other ingredients, and fry it up. It’s delicious. Mitch and I have both made them for holiday parties. And our teammates—many of whom have never seen or heard of a potato pancake—have scarfed them down.

As Mitch noted, there are all kinds of Jews. As I see it everyone in the world should be free to follow their own religious path. Being a professional football player, I have to miss some traditions and holidays. Do I want to miss them? No. While I did sit out Yom Kippur once during my freshman year in college when I wasn’t making it into games, as a pro in the NFL I don’t feel I have that option. There are 16 games in the regular season. Every game is just as important as the next so, if I’m healthy, I’m determined to play in every single one. It’s what I get paid to do, and I have a commitment to my teammates and my family to excel at my job. Sitting on the sidelines or missing a game because of a holiday is just not an option for me.

But I do go to temple when I get the chance. It’s important to me to honor tradition. Especially on the High Holy days, such as Yom Kippur, when you typically fast and reflect on your life and your actions. So if the holiday falls on the weekend, I try to make it work somehow. I’ve gone to services at the start of the holiday when it has fallen on Friday nights, but after that, I’m committed to the team and the upcoming game. It’s tough, but I know I’ll have my job for only a certain number of years, and I’ll have the rest of my life to go to services.

When my dad grew up everyone knew the story of Sandy Koufax, the Dodger star pitcher who refused to pitch the first game of the 1965 World Series because it was Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement that is considered the most holy day of the year. It was great that he did that, but comparing a baseball player sitting out a game to a football player sitting out is not an apples-to-apples comparison. There were plenty more games for Koufax to pitch. He started and lost game two, and went on to pitch—and win—the fifth and seventh games of the series.

When I asked my dad about Koufax, he had an interesting perspective. “I think in some ways Koufax made it worse for other Jewish players,” he said. “When you’re Koufax, and you’ve just won twenty-seven games, you can do what you want and no one says boo to you. But what if you’re not a star? There’s always going to be pressure to play.”

My dad is right. Within the culture of football, it’s hard to miss a game for religion—and it doesn’t make it any easier when people don’t understand the religion. But even if they do, it wouldn’t make much difference. There is definitely pressure to play come game day in the NFL no matter what the issue. People play when they are hurt, they play when they are sick, they play when their kids are getting born, and when their parents are dying. It is a competitive game. And unless you are a star, like Sandy Koufax, everyone can be replaced. So I play, because I love it, because I want to contribute, and because it’s my job.

I’m proud to be a role model to young Jewish kids and athletes, letting them know it’s possible for them to reach their goals. Mitch and I were honored at a fundraiser for a Jewish charity dedicated to meeting the nonmedical needs of seriously ill children called Chai Lifeline in 2015, and the response of the community was humbling. We were told it was a record turnout. People wanted to pose for pictures with us, and they asked for our autographs. As Mitch says, it was surprising because neither of us ever thinks of ourselves as celebrities. But to the people in the audience—kids and adults—we were a point of pride. It felt great.

I do wish that Passover would occur during the season. I’d love to host a seder for my teammates. Eating with your teammates—and really, with anyone—is an ancient recipe for connecting. Unfortunately, the season is over by the time the holiday rolls around.

Growing up, the Passover seder was always one of my favorite meals of the year. Seder means “order or arrangement” in Hebrew. So it is really a ritual in which we gather at the dinner table and recount the miracles that brought Jews out of slavery in Egypt. We take turns reading passages about the story of Moses. It’s always a jovial mood with kibitzing and jokes, that warm atmosphere comes with being around the people you love and are comfortable with. I think the mood is also helped by the fact you are supposed to drink four glasses of wine during the evening.

At the Weinsteins’ house, where we’d celebrate every year, they’d keep the meal loose and interesting. Seders weren’t just the strict reading of prayers and recounting of the story, which is important, because while you are sitting there reading, the smells of brisket and matzo ball soup are wafting around the house, making you hungrier and hungrier. They would have their sons sing the four questions, one of which asks, “Why is this night different from all other nights?” The answers are we recline—some people sit on cushions or pillows—during the meal to mark our freedom, we eat bitter herbs to remind us of slavery, we dip a vegetable into salt water to remind us of shed tears in Egypt, and we only eat matzo instead of leavened bread.

Because the seder is about thanking God for the liberation of the Jews, sometimes we’d have conversations about oppression and people of all faiths who live under modern-day pharaohs, which, for me, sort of takes the holiday rooted in the past and brings it into the present. I really liked that. When we were younger, the parents would hide a ceremonial piece of the matzo called the Afikomen and we would have to find it, get a reward, and then share it as “dessert.”

Our dad is one of the rare people on the planet who eats matzo year-round. Mitch and I aren’t big fans of the stuff. We tend to view matzo as a bland, crunchy carbohydrate-based food-delivery system. If you’ve never had matzo, imagine a giant saltine cracker without all that salt, and that will give you some idea of what we’re talking about. It’s thin, dry, and brittle unleavened bread.

Symbolically, of course, it’s crucial to Passover—reminding us that as our ancestors were fleeing through the desert there was no time to wait for dough to rise. But speaking from our own taste buds, it exists as a vessel for condiments, like an apple, nuts, and wine concoction called charoset. And of course, during the next eight days of the holiday, we put everything on it: peanut butter, butter and jam, cheese.

Speaking of Jewish meals, while I love our soul food—latkes, hamentashen, blintzes, knishes, gefilte fish, matzo ball soup, pastrami on rye—I was not raised in a kosher household. I eat everything and so do many Jews. Frankly, it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to observe kosher laws and make your way through the NFL as a 340-pound lineman who needs to eat huge amounts of protein. Teams are understandably not going to cater to one person’s religious dietary laws.

There have been instances where I’ve posted images of food on my Twitter feed and someone will invariably say, “That’s not kosher!” This is not the response I’m looking for. I never said I was kosher. It is interesting that some people want me, or expect me, to mirror their behavior. Personally, I take a modern view of religion and laws. While some of the dietary laws made perfect sense to protect people from sicknesses such as trichinosis, which is transmitted through pork, and hepatitis, which can be transmitted through shellfish, modern health laws and improved sanitary food practices have pretty much eliminated the health reasons that I believe at least partially inspired these prohibitions.

Adapted from Eat My Schwartz, copyright © 2016 by the authors and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

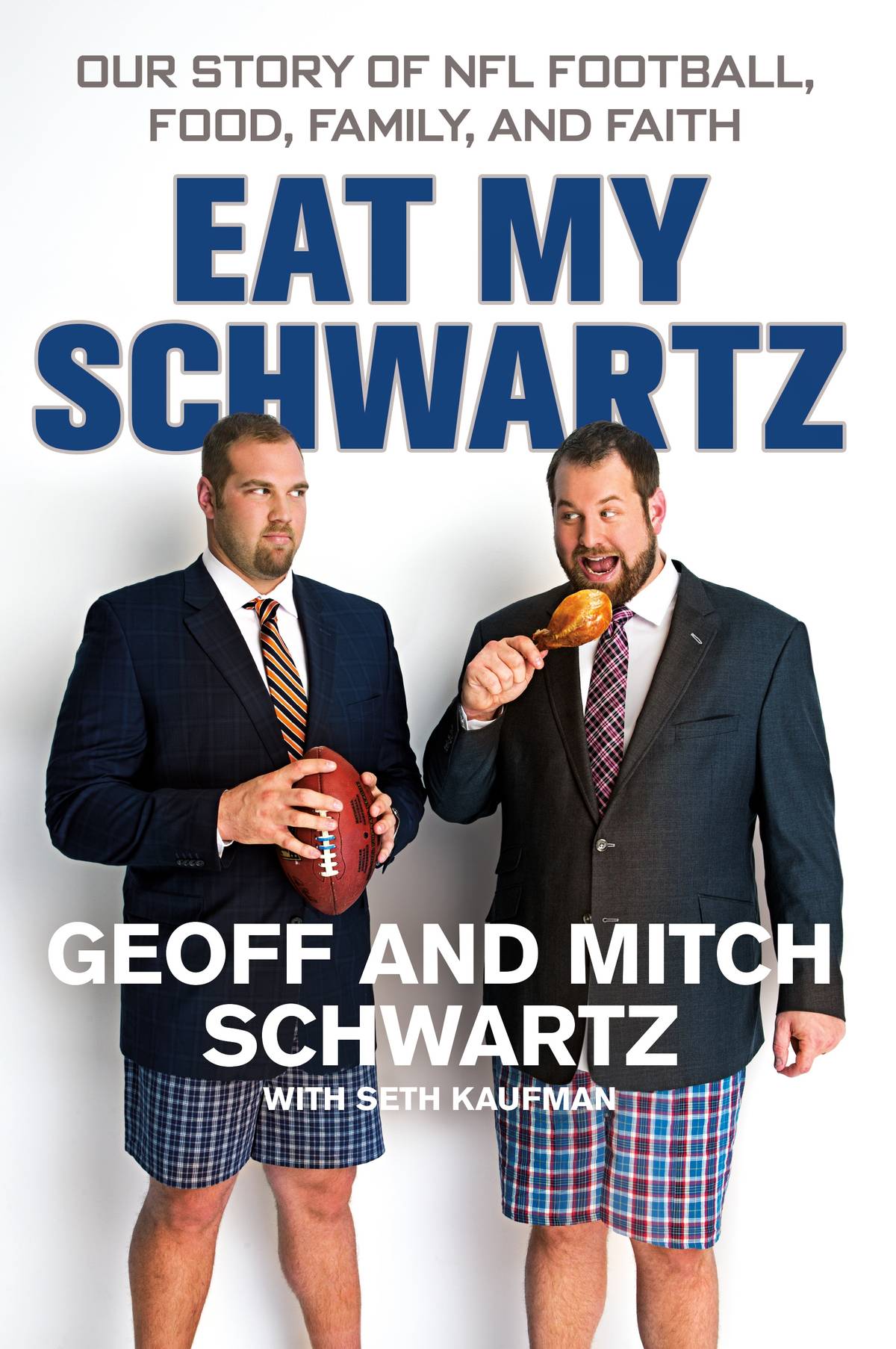

Geoff and Mitch Schwartz are both NFL linemen.