Who Will Prosper After the Plague?

The tech sector and the managerial class will get richer, while the rest of us become their serfs

The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to widen even further the growing class divides now found in virtually every major country. By disrupting smaller grassroots businesses while expanding the power of technologies used in the enforcement of government edicts, the virus could further empower both the tech oligarchs and the “expert” class leading the national response to the crisis.

In our increasingly feudal society, the small property owning yeomanry who operate the local businesses essential to Los Angeles shopping streets, and New York neighborhoods are already under threat and will be squeezed further by both the pandemic and its aftermath. But even more hard-pressed will be the growing, propertyless serf class that includes laid-off workers and the roughly 50 to 60 million workers in essential jobs, notes a new report from Richard Florida, and of those, 35 to 40 million require close physical proximity as opposed to those who can retreat to safety behind their computers. Roughly 70% of these workers are in low-wage professions, such as food preparation, and often, despite their increased risk, often lack health insurance from their employers.

Plagues, such as in the 14th century, may have wiped out as much as one third of Europe’s population, and devastated great Renaissance trading cities. In the Middle Ages, the wealthy sought safety in their country estates, much like the affluent now fleeing major European and American cities. Diets and survival rates varied enormously between the upper and lower classes. As one 14th-century observer noted, the plague “attacked especially the meaner sort and common people—seldom the magnates.”

But the wreckage also created new opportunities for those left standing. Abandoned tracts of land could be consolidated by rich nobles, or, in some cases, enterprising peasants, who took advantage of sudden opportunities to buy property or use chronic labor shortages to demand higher wages. “In an age where social conditions were considered fixed,” historian Barbara Tuchman has suggested, the new adjustments seemed “revolutionary.”

What might such “revolutionary” changes look like in our post-plague society? In the immediate future the monied classes in America will take a big hit, as their stock portfolios shrink, both acquisitions and new IPOs get sidetracked and the value of their properties drop. But vast opportunities for tremendous profit available to those with the financial wherewithal to absorb the initial shocks and capitalize on the disruption they cause. As in 2016, politicians in both parties have worked hard in the new stimulus to get breaks for their wealthy constituents, whether they are big retail chains, rich California taxpayers, or, in some cases, themselves.

Over time, the crisis is likely to further bolster the global oligarchal class. The wealthiest 1% already own as much as 50% of the world’s assets, and according to a recent British parliamentary study, by 2030, will expand their share to two-thirds of the world’s wealth with the biggest gains overwhelmingly concentrated at the top 0.01%.

In an era defined by “social distancing,” with digital technology replacing the analog world, the tech companies and their financial backers will prove the obvious winners. In a sign of what’s to come, tech stocks have already soared.

The biggest long-term winner of the stay-at-home trend may well be Amazon, which is hiring 100,000 new workers. But other digital industries will profit as well, including food delivery services, streaming entertainment services, telemedicine, biomedicine, cloud computing, and online education. The shift to remote work has created an enormous market for applications, which facilitate video conferencing and digital collaboration like Slack—the fastest growing business application on record—as well as Google Hangouts, Zoom, and Microsoft Teams. Other tech firms, such as Facebook, game makers like Activision Blizzard and online retailers like Chewy, suggests Morgan Stanley, also can expect to see their stock prices soar as the pandemic fades and public acceptance of online commerce and at-home entertainment grows with enforced familiarity.

Growing corporate concentration in the technology sector, both in the United States and Europe, will enhance the power of these companies to dominate commerce and information flows. As we stare at our screens, we are evermore subject to manipulation by a handful of “platforms” that increasingly control the means of communication. Zoom, whose daily traffic has boomed 535% over the past month, has been caught sharing data from its users with its clients widely, and without approval. Not surprisingly these platforms are most widely deployed in tech centers like the Bay Area, Seattle, and Salt Lake City as opposed to areas like Las Vegas , Tucson, or Miami where more jobs require close physical proximity.

The modern-day clerisy consisting of academics, media, scientists, nonprofit activists, and other members of the country’s credentialed bureaucracy also stand to benefit from the pandemic. The clerisy operate as what the great German sociologist Max Weber called “the new legitimizers,” bestowing an air of moral and technocratic authority on the enterprises of their choosing. The members of this class are concentrated in professions—including teaching, consulting, law, government work, and the medical field—whose numbers have grown in recent decades. Some professions once more tied to the private economy, such as doctors, have become subsumed into bureaucratic structures in the United States, and, in the process of shifting from private to public sector, have gone from being conservative to increasingly progressive professions.

Members of the clerisy are likely to be part of the one-quarter of workers in the United States who can largely work at home. Barely 3% of low-wage workers can telecommute but nearly 50% of those in the upper middle class can. While workers at most restaurants and retail outlets face hard times, professors and teachers will continue their work online, as will senior bureaucrats.

The second half of the 20th century saw the rise, across much of the world, of a growing class of small property owners. But recent decades have been tough on small businesses, which have generally shrunk while public sector administrations have grown. They have also had a more difficult time adjusting to the growth of regulation than larger firms, which tend to be more adept at adapting to government strictures.

The decline of the small property owning yeoman class can be seen in the falling rates of business formation as well as declining homeownership, particularly among the young. The pandemic threatens to accelerate this decline to an extent even greater than the 2008 financial-crash-induced Great Recession.

The biggest winners in the fallout from the coronavirus are likely to be large corporations, Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and government institutions with strong lobbies. The experience from recent recessions indicates that big banks, whose prosperity is largely asset-based, will do well along with major corporations, while Main Street businesses and ordinary homeowners will fare poorly. As one conservative economist put it succinctly in 2018: “The economic legacy of the last decade is excessive corporate consolidation, a massive transfer of wealth to the top 1% from the middle class.”

The hardship caused by today’s crisis is particularly evident in retail, where 630,000 businesses have already shut down. Supply chain problems related to the Xi-Trump, China-U.S. trade war had already threatened many U.S. industries, but since the pandemic some 87% of small-business owners now say that they are struggling in a Wallet Hub survey, and a full third predict they will fail if conditions don’t change in the next three months.

Restaurants, small retail establishments and “personal service” establishments like salons and gyms will experience the greatest pain. In the past their primary selling point against larger firms has been their independence and familiarity with customers. Many have taken on debt they may have trouble to pay off. According to the JP Morgan Institute, 50% of small businesses have a mere 15 days of cash buffer or less. If the shutdown lasts much longer as many as three-quarters of independent restaurants simply won’t make it.

Meanwhile, as small independent outlets are going out of business, Wall Street-financed restaurant chains, particularly those that have managed to build effective online formats and boast germophobic environments are far better positioned to survive. If the current regime remains in place, you might expect your local taco stand to be replaced by the likes of Taco Bell or Chipotle and the family Chinese place to be bought out by Panda Express, Pick Up Stix, or perhaps some other more upmarket, well-financed equivalents.

In the Middle Ages, many former citizens, facing a series of disasters from plagues to barbarian invasions, willingly became serfs. Today, the class of permanently propertyless citizens seems likely to grow as the traditional middle class shrinks, and the role of labor is further diminished relative to that of technology and capital.

In contrast to the old unionized workers, many people today, whether their employment is full-time or part-time, have descended into the precariat, a group of laborers with limited control over how long they can work, who often live on barely subsistence wages. Nearly half of gig workers in California live under the poverty line.

To these indignities, the pandemic also threatens the health of many workers, including those employed at the grocery stores, senior facilities, and warehouses, now keeping the country alive. Not only is their current and future employment not secure, but their workplaces pose obvious dangers of exposure to the virus.

This is particularly clear at the virus’ epicenter in New York. Better-off New Yorkers may avoid the subway—as they should—but many members of the working class, including the people who care for the sick and old, cannot afford that luxury.

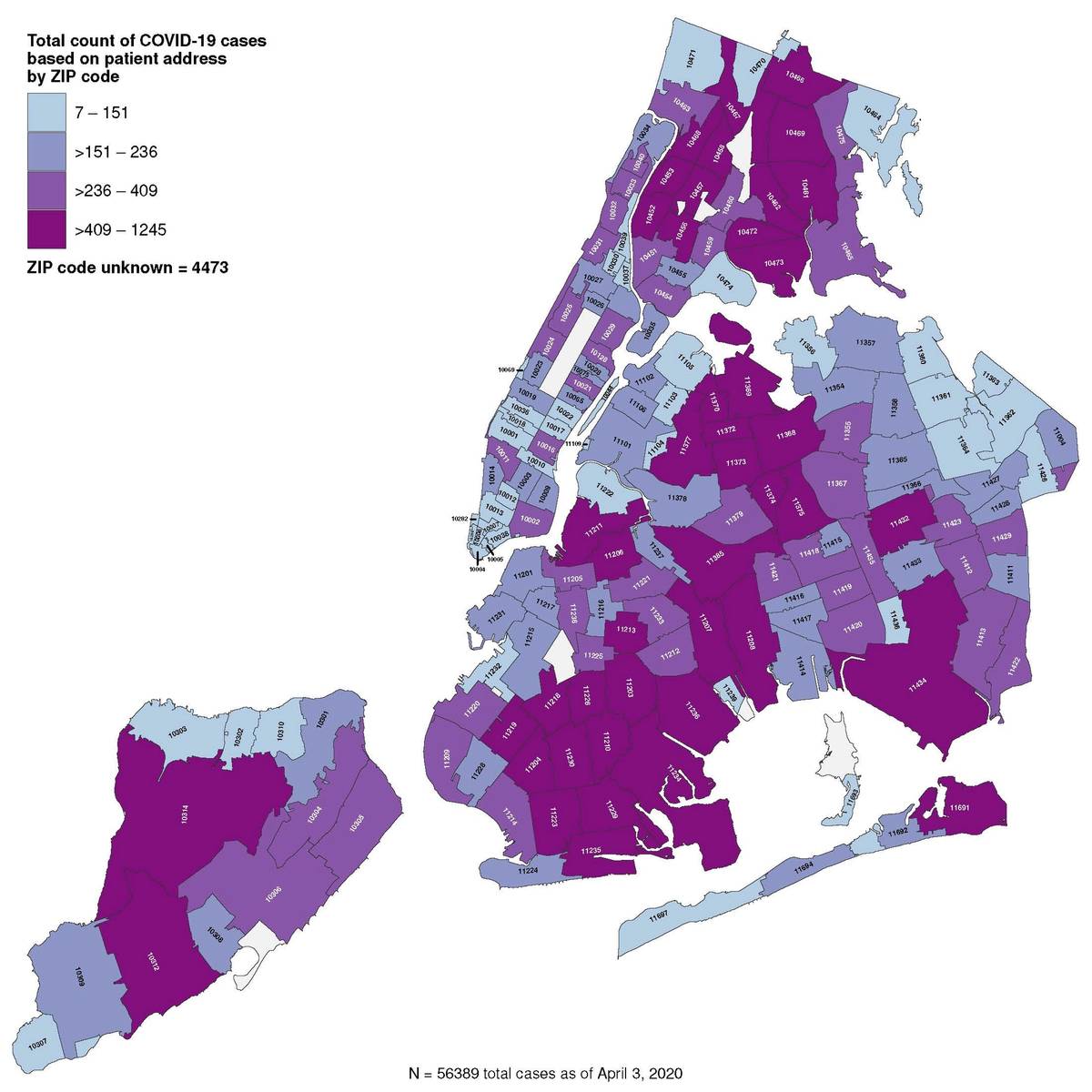

New York has among the highest percentages of jobs that require close physical proximity: almost 1 in 3. They tend to be concentrated in dense inner-city areas but not in the rarefied atmosphere of swank Manhattan or brownstone Brooklyn, where information era workers can work at home. Instead, as the map of infections developed by the city shows, the worst levels are in decidedly working-class, transit-dependent places like the Bronx, east Brooklyn, and northern Queens, also home to a large Chinese immigrant community. Even worse, many of the people living in those hardest hit areas lack adequate health care coverage, a major disadvantage amid a pandemic.

Historically, pandemics have tended to spark class conflict. The plague-ravaged landscape of medieval Europe opened the door to numerous “peasant rebellions.” This in turn led the aristocracy and the church to restrict the movements of peasants to limit their ability to use the new depopulated countryside to their own advantage. Attempts to constrain the ambitions of the commoners often led to open revolts—including against the church and the aristocracy.

As the impact of the pandemic ripples through the economy, “the gulf between the knowledge economy and the gig economy” suggests the Toronto Globe and Mail’s John Ibbitson, will wither. As steady and well-paying jobs disappear, the demands for an ever more extensive welfare state, funded by the upper classes, will multiply.

Like their counterparts in the late 19th century, the lower-class workforce will demand changes. We already see this in the protests by workers at Instacart delivery service, and in Amazon warehouse workers concerned about limited health insurance, low wages, and exposure to the virus.

As the virus threatens to concentrate wealth and power even more, there’s likely to be some sort of reckoning, including from the increasingly hard-pressed yeomanry.

In the years before the great working-class rebellions of the mid-19th century, Alexis de Tocqueville warned that the ruling orders were “sleeping on a volcano.” The same might be seen now as well, with contagion pushing the lava into the streets, and causing new disruptions on a scale of which we can’t predict.

Joel Kotkin is the Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and executive director of the Urban Reform Institute. His new book, The Coming of Neo-Feudalism, is now out from Encounter. You can follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin.