Levinas Would Have Banned Facial Recognition Technology. We Should Too.

The surveillance state is a deeply threatening and immoral structure for human social existence. It’s here now.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before.

There’s a new technology in town. A few years ago it seemed like a pipe dream, but it’s now arrived on the commercial market in a big way. Large corporations are lining up to use it even as watchdogs point out serious potential for abuse. Reporters look into it, agree that there’s a problem, and pen dozens of articles fretting about the downsides, demanding regulation and responsible use. The public grows concerned, and then they grow resigned. Meanwhile, the technology is adopted. Sometimes it is well regulated, more often it is not. There are a few horror stories. We learn to live with it. We move on.

This is the ethical life cycle of modern technology, and its major problem is that it doesn’t know how to distinguish between technologies that complicate morality and those that destroy it—that is, it lacks the ability to say no, absolutely not. All technologies have some redeeming value, goes the underlying assumption, and while there’s a short list of technologies we’ve decided should never be used—certain weapons and forms of genetic engineering most prominently—they nevertheless persist, and there isn’t a mechanism for adding to that list. We can turn the volume down, but we cannot turn it off.

This failure, more than anything else, explains why facial recognition software has continued to rapidly develop and proliferate across different sectors of society despite the certainty that it will be used for abusive and dehumanizing purposes.

Perhaps there is some universe in which the benefits of facial recognition could outweigh the dangers, but it isn’t this one. This past June, the ACLU lodged a complaint against the Detroit Police Department for arresting a man based solely on a piece of software that had misidentified him from a photograph (the man is Black, and facial recognition software is notoriously bad with Black faces). In Maryland, a Washington Post report revealed that ICE had been combing through driver’s license photos to identify the faces of undocumented immigrants. Most chilling of all, the Chinese government has developed and deployed cameras and facial recognition software to identify members of the oppressed Uighur minority based on facial features and then systematically track their movements. Technologies like facial recognition are integral to the functioning of China’s police state and its imprisonment of hundreds of thousands of Uighurs in forced labor and “reeducation” camps. Today, several countries, including the United States, maintain facial records for millions of their own citizens.

In America, concerns about these surveillance technologies are very often focused on law enforcement agencies, many of whom have already built large caches of facial information. Indeed, a handful of municipalities, most notably San Francisco and Boston, have already banned its use, and in the wake of the George Floyd protests both Amazon and IBM have stopped selling their tools to law enforcement. But facial recognition isn’t just a problem when it’s in the hands of police departments. In terms of sheer volume of facial recognition data collected and exploited, it’s entirely possible that social media companies like Facebook are far ahead of what’s been accomplished by government agencies.

Through search engines like PimEyes, based in Poland, anybody with an internet connection can identify a person in a photograph based on other images that are publicly available online. Here in the United States, Clearview AI has mined the internet for faces and sold its tools to the Justice Department, ICE, and several major corporations. In 2019, the landlord of a rent-stabilized apartment complex in Brooklyn attempted to install a facial recognition system to access the building. In exchange for accepting these dangers, we have received the rather meager benefit of being able to unlock our phones a few seconds faster.

From a privacy perspective, these developments are just one piece of a larger trend toward cheaper and more powerful surveillance tools, and it is tempting to deal with facial recognition’s utility alongside biometric tracking and data mining techniques. But facial recognition is not just another tool, because my face is not just another bit of personal information. More than any other aspect of ourselves, it is the face that conveys our uniqueness and humanity. It is also, for the French Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, the source of ethical obligation itself.

If the face is the portal through which all ethical commitment flows, then facial recognition technology is nothing less than an end run around ethics itself.

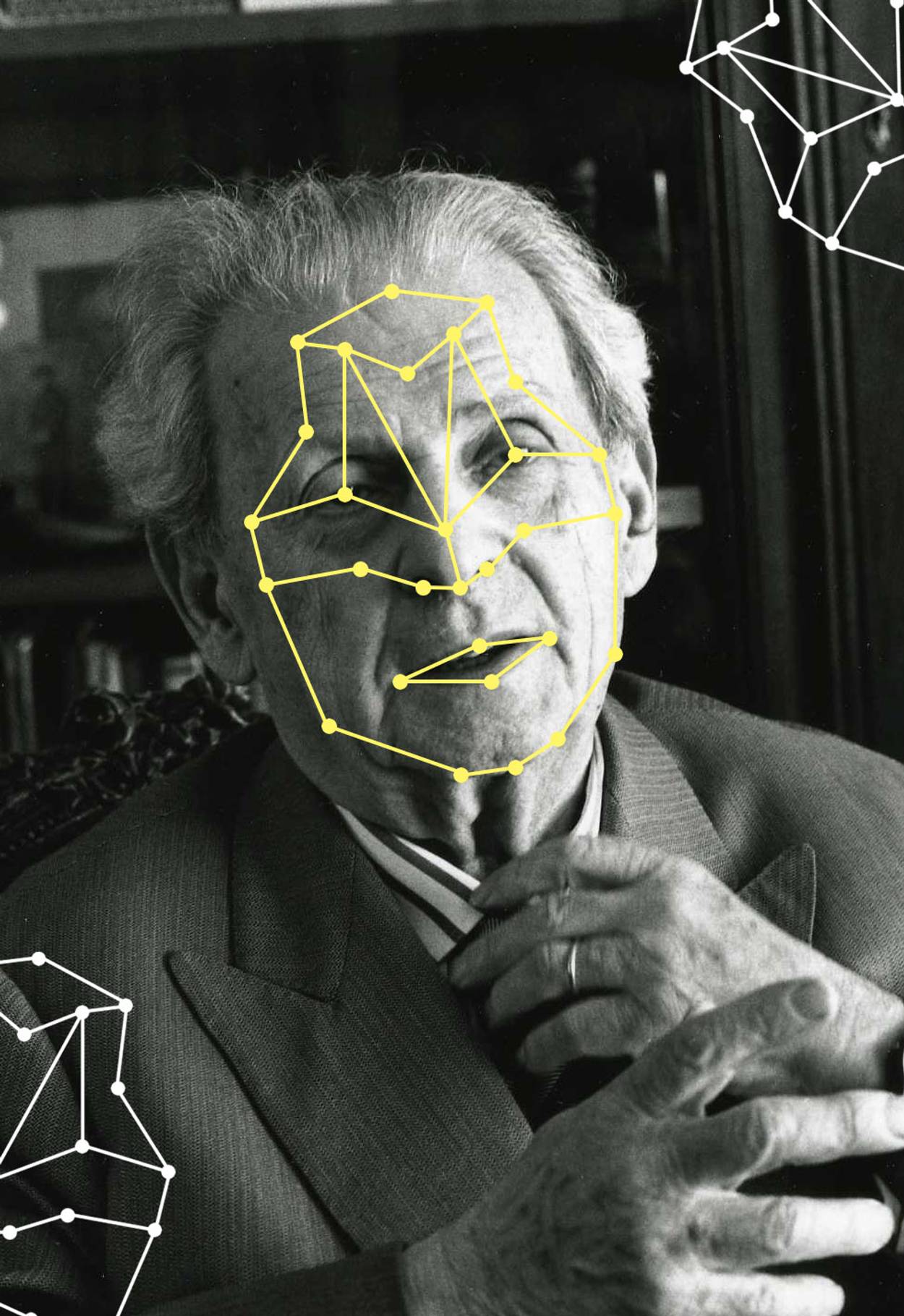

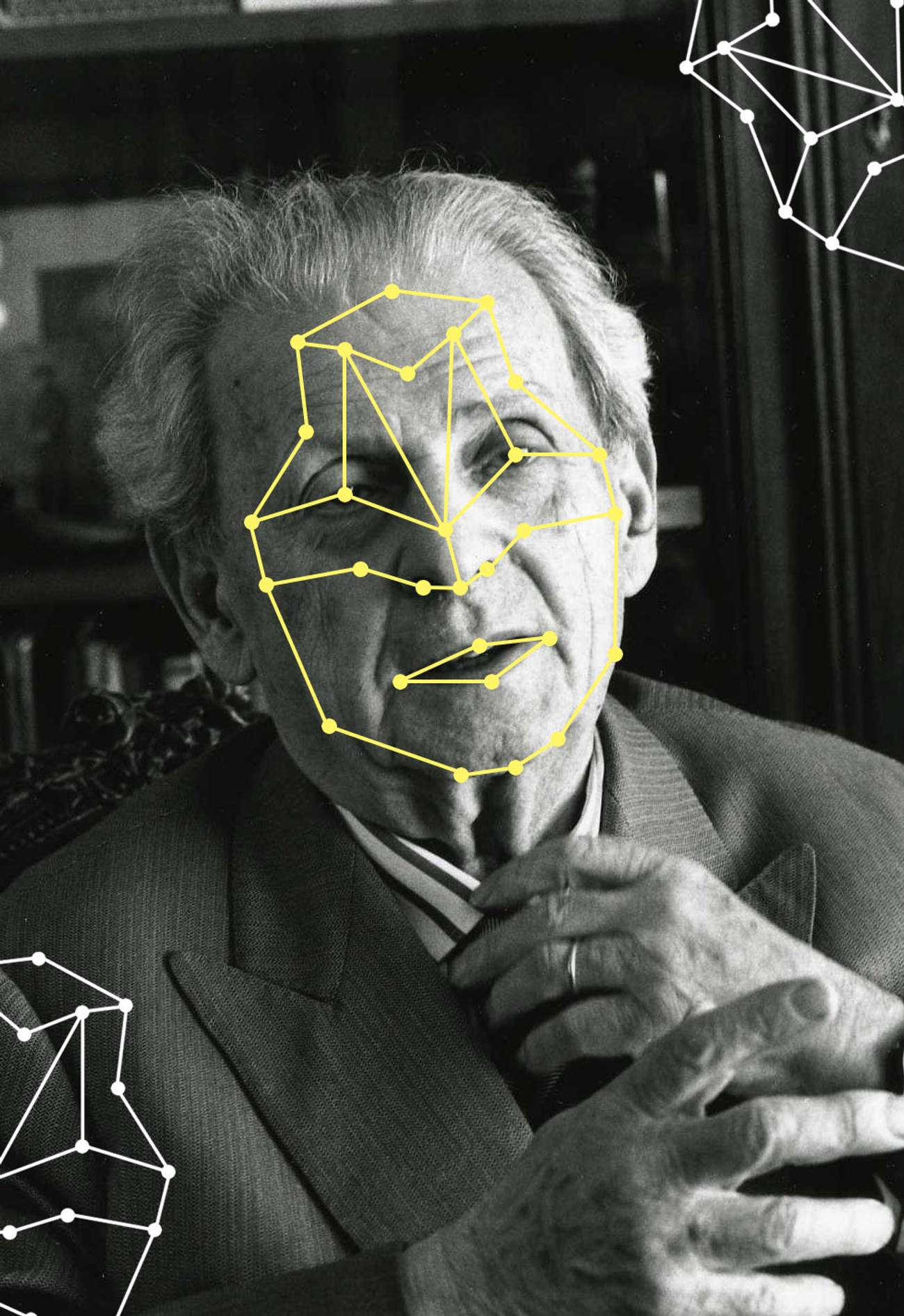

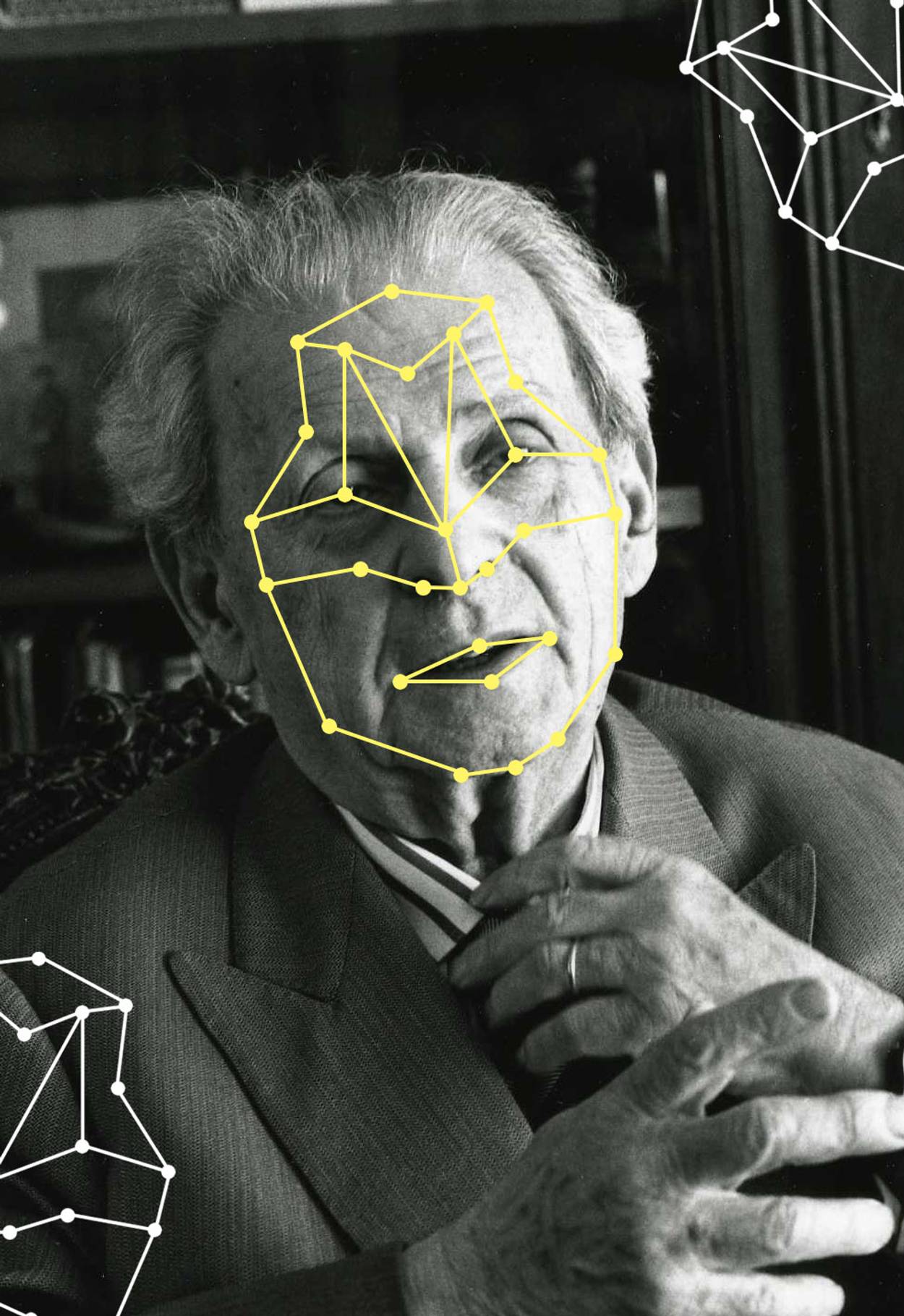

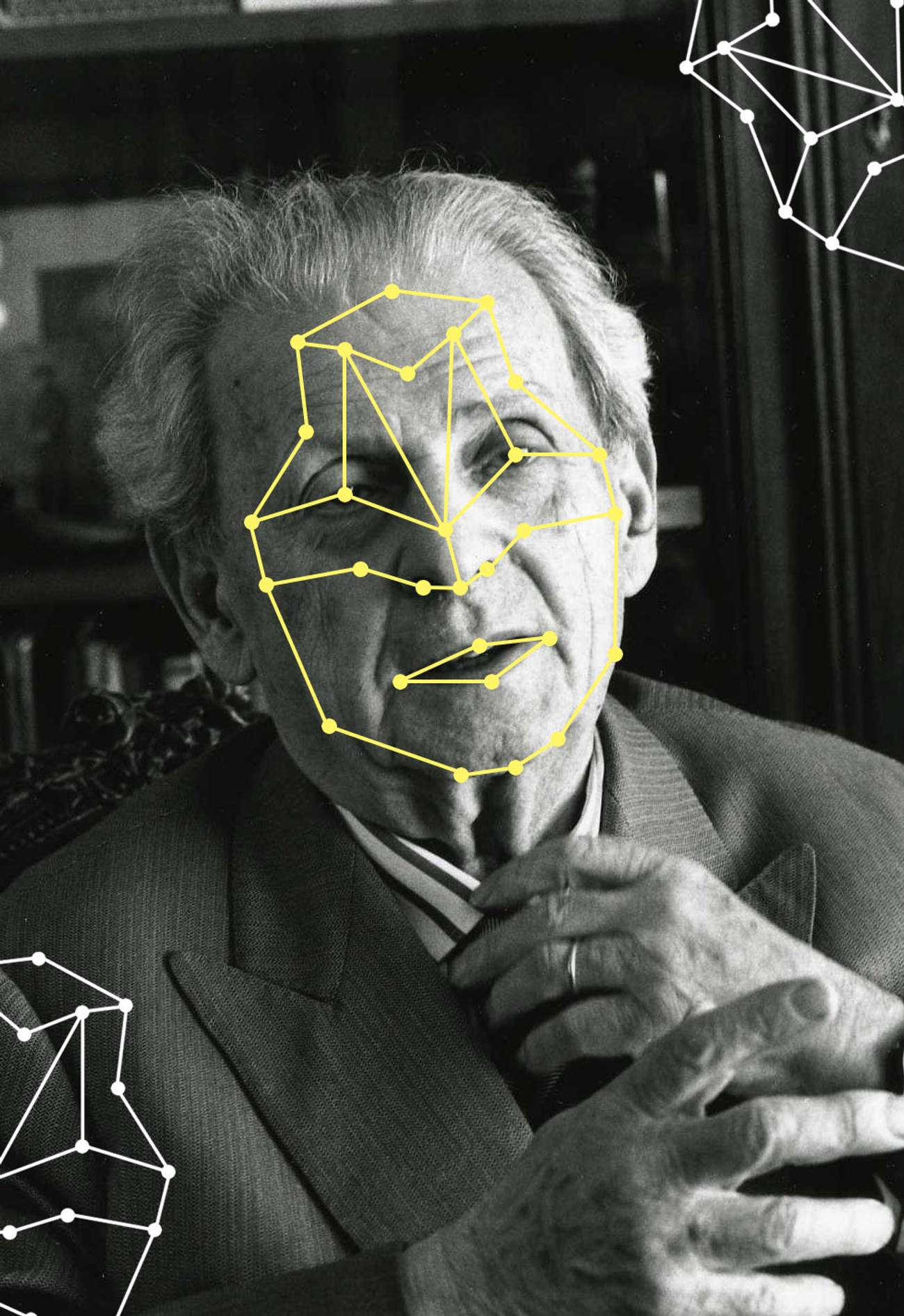

Levinas was primarily a philosopher of ethics. In the wake of the Holocaust, his major project was the development of a new foundation for ethics, one grounded not in God or the pure practical reason found in Kant’s categorical imperative, but in other human beings. Levinas’ line of inquiry bears similarities to other 20th-century philosophies rooted in Jewish ethics, including Martin Buber’s notion of the “I-Thou” relationship. But it is also linked to post-Heideggerian thinkers, including Jean-Paul Sartre, whose conception of an existence in which we are defined by others’ views of us is summed up in the famous line: “Hell is other people.” Levinas began with premises similar to those of his contemporaries: Yes, the people around us affect us deeply; in fact, it is only by encountering them that we can have ethics at all. This encounter, for Levinas, isn’t some abstraction. The ethical obligation emerges, very specifically, when we apprehend the face of the other. The power of the human face is central to Levinas’ ethical philosophy, and it is a subject to which he returned frequently throughout his writings.

For Levinas, the face is powerful because it is incredibly vulnerable. “The skin of the face is that which stays most naked, most destitute,” he says in a 1982 interview, published as Ethics and Infinity. “The face is exposed, menaced, as if inviting us to an act of violence. At the same time, the face is what forbids us to kill.” This instantaneous shift—we see the potential for violence but then immediately shrink from it—is of supreme importance because it is the original source of ethical obligation. Much as many astronauts who see the whole Earth from space have been struck by its fragility and a desire to care for it, the face of another person, which communicates both their fragility and their humanity, stirs in us a sense of profound responsibility.

But the face is also important for Levinas because it doesn’t have to mean anything else—it is, in his words, “signification without context.” In the ideal encounter, you experience the face of the other without actually noticing anything about it, not even eye color. Given what we know today about unconscious bias, this is perhaps a little naïve; people may not notice eye color immediately, but they certainly do notice race. Still, even if a pure encounter is not possible, Levinas’ point is that there is something in the human face that cuts through so many of the ways that we define ourselves and are defined by our bodies, to reveal a single essential quality: that the person you are looking at is not you, and that in recognizing this it obligates you, first to preserve it, and then to lead an ethical life. “There is a commandment in the appearance of the face, as if a master spoke to me,” Levinas said. The details of Levinas’ face philosophy are sometimes obscure and difficult to follow, but the face he is describing is always real, never a metaphor; faces—especially the faces of strangers—actually matter.

Levinas died in 1995 and so did not live long enough to speak to the uniquely dehumanizing effect of facial recognition technology, but his philosophy, more than any other, anticipated its dangers. If the face is the portal through which all ethical commitment flows, then facial recognition technology is nothing less than an end run around ethics itself. Not only do tools like these relieve people from the need to look at one another, but they do so by transforming the face into just another data set, one in which the face’s declaration of humanity—the very thing that stirs us to be ethical—simply evaporates. The propensity of facial recognition technology to cause harm—indeed, the inevitability that it will do so—is anything but an accident. It is, instead, the inescapable result of an effort designed to reduce interaction between humans and to surrender the aspect of their bodies which triggers an instinct to give a damn into the cold calculations of a digital database.

If facial recognition truly is a technology that not only has unethical uses but subverts ethics itself, then we must stop debating when it is acceptable and instead insist that it should have no place in our society whatsoever. At the end of 2019, Congress put forward a bill to ban the use of biometric entry systems, including those that use facial recognition, in all public housing. This is a start but our efforts must go far beyond this. It is especially the most dangerous technologies that are hardest to relinquish for those who have adopted them. In the face of this one, we must act to curtail it before it is too late.

David Zvi Kalman is a Fellow in Residence at the Shalom Hartman Institute and the founder of an independent Jewish publishing house.