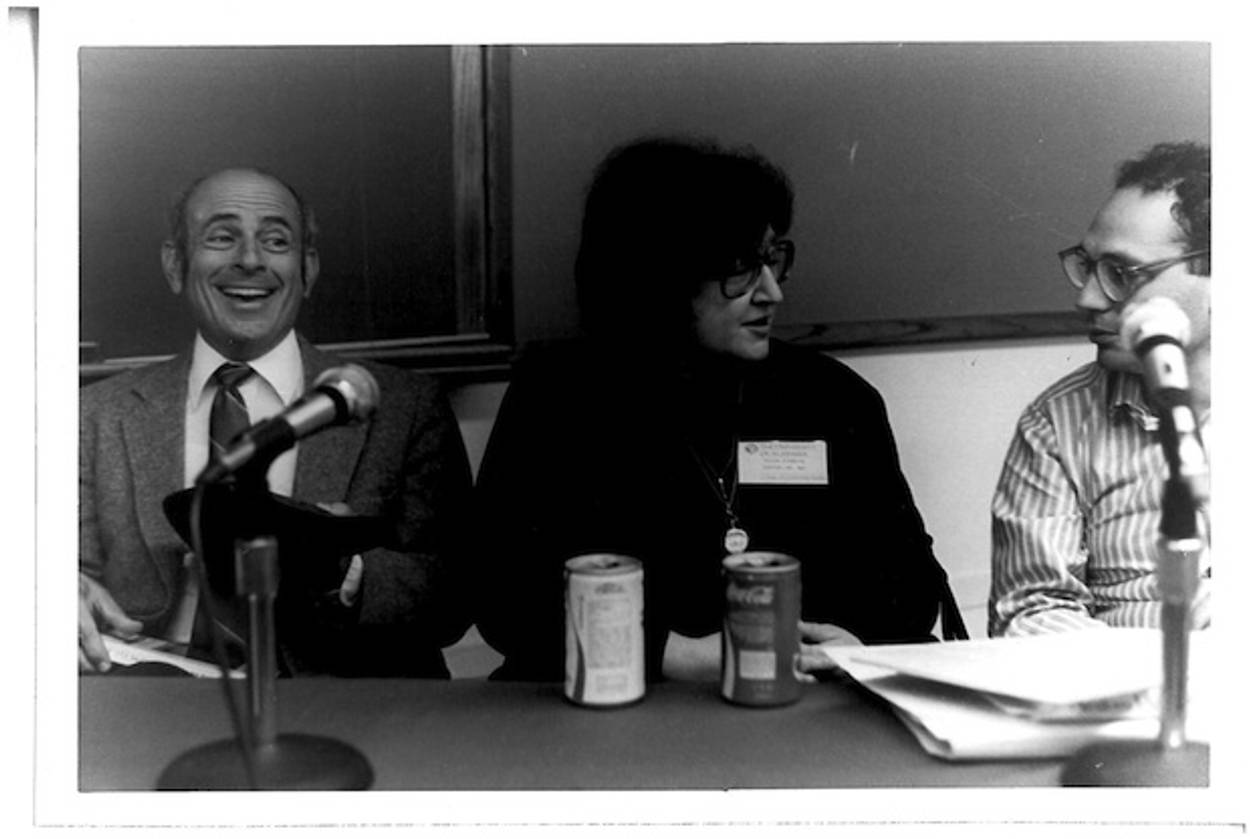

Louis Simpson (1923-2012)

The Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and critic was 89

Born an Aries in Kingston, Jamaica of Russian-Scottish descent, poet Louis Aston Marantz Simpson left us behind this week after a long struggle with Alzheimer’s. For a poet whose concision bordered on the succinct, whose writing seems, at first, deceptively simple, his life proves that he was not a man of few words–rather, he was a man who chose them with extreme care.

He had his struggles with identity, as do we all, but how many of us have suddenly discovered that one grandmother lights Shabbat candles or that the other grandmother was of African descent? Then there was a divorce, a sudden death, disinheritance. These are some of the twists, surprises, the revelations that informed his poetry. So too did his experiences serving as a World War II Army combat infantryman in Western Europe. He was injured in battle. He suffered from a “breakdown,” which today might be recognized as PTSD and treated accordingly, but in his day would result in a brusque hospital sojourn.

And while he recovered, he published multiple books of poetry. He published criticism of Pound, Eliot, and William Carlos Williams. He got his master’s and doctorate from Columbia University, teaching both there and at UC-Berkeley before settling down at SUNY-Stony Brook. In addition to the 1964 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, he won the 1957 Rome Prize and the 1976 American Academy of Arts and letters award in literature.

Despite being born in the same hemisphere, by virtue of his foreign birth and upbringing, his choice to come to America makes him as much an immigrant as any of the others who arrived in 1940. His poetry explored his new world and he directed some of his work to an examination of America, seeking to define and quantify the place he chose as home. A fellow undergrad with Allen Ginsberg and a teacher at UC-Berkeley in the early 1960’s, his presence on the precipice between old ways and new ideologies fueled his writing.

His experience speaks to diaspora and homecoming, being part of history as well as an observer of the passing time, incorporating influences from within his own cultural heritage and beyond it. He was a poet of dichotomies–immigrant and citizen, veteran and optimist, formalist and innovator–trying to use language to make sense of it all, to allow contrasting, even conflicting, identities to coexist. A rather familiar Jewish perspective, nu?

We honor his ability to straddle two worlds and his attempts to place them in context, much in the way of Bellow, Malamud, or Roth. We thank him for the moments, both riotous and meditative, that he created for us. For the places he described in poems like A Clearing, places he made for us:

a clearing in the shadows

and above it, stars and constellations

so bright and thick they seem to rustle.

And beyond them – infinite space,

eternity, you name it.

We hope that he found such a place himself.

Amelia Cohen-Levy is a writer and editor living in Northern Virginia. Her work has appeared in The Ilanot Review, Moment Magazine, Jewcy, 580 Split, and elsewhere.