Oakland’s Educational Bureaucrats Steamroll Parents and Kids

Conversations with some of California’s most vulnerable families show they have become the targets of increasingly autocratic officials entrusted with the education of their children

“The pandemic kind of destroyed my kids,” Maplean told me. Her son, Da’vine, is 17 years old and a high school junior in Oakland. “Kids like him have to be in school,” she said. “It was really, really rough for him doing online classes. It put him back even farther than what he was.”

Last year, Oakland saw a surge in shootings, assaults, and homicides. Maplean tries to keep her kids home not only because she is still concerned about COVID, but also due to the increased threat of gun violence in their neighborhood—itself a product of policies that put school-age kids at risk by disrupting normal patterns of socialization for the most vulnerable.

“For the kids that don’t have anything to do with their lives, don’t have any support groups, of course they’re going to go out there and think it’s OK to start doing more violence,” Maplean told me.

Everything that was hard before COVID is worse now in Oakland. Prices are higher, and as a single parent Maplean feels the financial strain. “I used to take my kids out a lot,” she said. “Now I have to be really cautious. Money-wise, I just don’t have it.”

Maplean thinks masks, testing, and other mitigation measures were necessary for schools to reopen, but she knows that virtual learning took an emotional toll on her son. Da’vine once took pride in his schoolwork and good grades, so falling behind had an impact on his self-esteem. “He comes home and tells me he doesn’t know how to do the work,” Maplean said. Wealthy people “are able to make sure their kids get the education that they need, but what about the less fortunate ones? What about us?”

The San Francisco Bay Area, where Maplean lives, was once considered a center of tolerance and personal freedom. Since the pandemic began, it has become notorious for its inequality and dysfunction, brought about in part by rigid and often evidence-free COVID policies. In San Francisco and other Bay Area cities, unvaccinated people—including children—are barred from restaurants, movie theaters, gyms, and other indoor spaces. Schools in the Bay Area were closed for longer than almost everywhere else in the country, making the experience of children and parents in the educational system where I once worked an ongoing experiment in the costs of isolation and desocialization for some of the most disadvantaged children and families in America.

Like Los Angeles, some parts of the Bay Area tried to implement COVID vaccine requirements in schools but were forced to postpone them when thousands of kids didn’t meet the deadlines. Gov. Gavin Newsom has also recently announced an upcoming statewide mandate for children in grades 7-12, making California the only U.S. state in which COVID vaccines will be a condition for in-person school next year. The state legislature is currently set to vote on bills that would expand the mandate to include grades K-6, eliminate personal-belief exemptions, and enable kids 12 and up to get vaccinated without parental consent. Although the stereotype persists that only white Trump voters are unvaccinated, the Black and Latino residents of blue California have the lowest levels of vaccine uptake for both adults and teens.

Many of the parents I spoke with in order to better understand the toll of COVID mandates—imposed in many cases with little to no scientific consensus about their likely efficacy—are working-class mothers whom I know from when I was a public school teacher in Oakland. They preferred that I only use their first names, which makes sense, given their vulnerability to the whims of an increasingly autocratic, intolerant, and punitive bureaucracy that has shown no interest in putting kids or families first.

None of the parents I spoke with described themselves as “anti-vax.” Their kids have received all of their regular childhood vaccines, and some of their kids have been vaccinated against COVID, but they believe the COVID vaccines should be a personal choice. They spoke to me about the losses they have experienced, how school closures affected their families, and the ways in which institutions they once trusted have failed them. This is about much more than a school policy or a vaccine: It’s about the fact that parents have been sidelined, ignored, and left out of crucial decisions about their children’s lives. Their experiences and opinions about COVID and COVID restrictions are all different, but they share the same overwhelming sense that something in our state is going terribly wrong.

Even though Maplean often worries about her kids’ safety at school, she doesn’t support the vaccine mandate. “It’s not up to the school district,” she said. “It’s actually up to us parents.” At first Maplean did not want to get her kids vaccinated, but she’s glad she did. Her daughter has allergies, so Maplean brought an EpiPen with them to the vaccination site and was nervous that she would have to use it if her daughter had a reaction. Because of this, she understands why some parents have anxiety about the vaccines.

To date, 30% of students 12 and up in Oakland public schools have not verified their vaccination status, even though the district threatened to unenroll them or put them into “independent study” (online learning). “I just feel like the school district is pushing parents, especially African Americans, to force them to get their kids vaccinated,” Maplean said. As for why she thinks Black students have lower rates of vaccination, their parents “don’t trust too many people in Oakland. We as African Americans have trust issues with certain things of what we put in our kids’ bodies. I have that issue too.” Some of this hesitancy may be connected to the fact that COVID deaths have disproportionately affected minorities. Maplean feels that the city and the hospital system failed to provide adequate care: “They said ‘Forget these people, they’re going to die anyway’… And why? It’s because we’re poor.”

Ofelia, whose sons Jesus, 17, and Cesar, 16, are in high school in San Leandro, told me that it feels like the state’s approach to COVID has been like a lab experiment. “They have no control, so they’re trying to put everyone in a box,” she told me. “They’re saying, ‘Let’s see if this works, and if this doesn’t work, then we’ll try this, and then if that doesn’t work, then we’ll try this.’” During online learning, her sons’ school and their teachers did as much as they could to help them, but it was still challenging. “Emotionally, I think they checked out after the first month,” Ofelia said.

Ofelia was already under the worst possible strain; her other son died suddenly in June 2020 at age 24. “I can’t remember a lot of it because I was so distraught,” she told me, “but because of the pandemic we couldn’t have a decent rosary for him and we couldn’t have a vigil for him.” Only 10 people could attend the funeral and they had to stay 6 feet apart. It was difficult to get any emotional support. “That was really hard because I have a big family,” she said. “It was really hard to go through that and still have so much restrictions … You don’t realize that you’re going to have this loss in your family and then to still be so confined and you can’t do anything. It just makes it 10 times worse.”

Ofelia did not oppose the lockdown or the school closures because she felt that so much was uncertain, and both of her sons got the COVID vaccine. However, she does not think it should be mandatory. “This was something that I think they were throwing on everyone,” she said. “There wasn’t a lot of research about it. And it was not a choice. At this point it’s not your choice to get it—it’s either you get it or you can’t go into the restaurant to eat … Either you get it or you can’t go to school.” Ofelia told me that she has family members who passed away from COVID, but she firmly believes vaccination should be a personal decision. “Everybody has their reasonings,” she said.

Shanita recently moved from Oakland to Sacramento with her 14-year-old son, Anthony. When Anthony was in online learning, Shanita was an essential worker and could not stay home with him, so she was relieved when school reopened. The Sacramento City Unified School District originally mandated the vaccine deadline for Jan. 31, but has pushed it back because only 55% of students 12 and up fulfilled the requirement. “The vaccination set in well with me, and I’m fine with it,” Shanita told me. But Anthony did not want to get it, and Shanita does not want to force it on him. “He does have his rights, even though he’s a child,” she said.

For Edith, another parent from Oakland, the pressure for kids to be vaccinated has amplified the anxiety she already felt during the school closures: “It’s sad for us as parents. I feel like us parents are going through so much stress worrying about what’s going to happen to our kids.” Her son Ivan is 13 and has autism. During the school closures he fell behind socially and in his language skills. Before online learning started, Ivan loved to draw and did it constantly, both at home and at school. Now he prefers to go on the computer, and Edith has to limit his screen time.

When school reopened in April 2021, Ivan couldn’t go because the bus service he was entitled to as a special education student was not routed to his home on time. This happened again this school year after Ivan tested positive for COVID and had to quarantine. When the quarantine period was over, the bus didn’t come to pick him up, causing Ivan to miss even more school. Edith still remembers Ivan’s face the day he tested positive—she had never seen it like that before. He told his mom not to get close to him and asked her if he was going to die. “Because he sees it on the news and hears the constant talk, I feel like it’s damaging him in a way,” Edith said. Kids can’t enjoy their childhood, “because all this worrying about, ‘Don’t do this, don’t do that, you gotta wear this, you gotta stay away, you can’t be close to your friend, you can’t see smiles.’”

Since Ivan has autism, masking and social distancing policies and the heightened anxiety that pervades school life are affecting him a great deal. They are also affecting Edith’s other son. “They’re not going to live the life that I lived when I was in school,” she said. “I never had to worry about wearing a mask. Back then I used to play in the mud. I used to play outside in the dirt, and germs were okay.”

Because she feels like public health recommendations keep changing, Edith is not comfortable with Ivan getting the vaccine yet—who is to say that the recommendations won’t change again? Being commanded and sneered at by high-handed local, state, and federal bureaucrats has done little to convince Edith that her fears are wrongheaded. She thinks many parents are vaccine-hesitant precisely because the schools have been pushing it so hard without asking for their input. “Sometimes I feel like we parents don’t count,” she said.

All they’re doing is creating torment for families and individuals that don’t really deserve it.

In more affluent Bay Area communities outside Oakland, vaccination uptake has been higher, but the social consequences for families that choose to opt out can also be enormous. In Berkeley, where the typical home value is $1.6 million, 91% of white and Asian high school students met the district’s vaccine requirement. I spoke with Berkeley parent Dan McDunn, whose kids did well during online learning because they had plenty of access to computers, outdoor space, and their own rooms. Yet they are now facing their own experiences of exclusion, isolation, and punishment due to choices that might strike most parents as entirely normal—or at least worth talking about.

When the vaccine rollout began, Dan was open to the idea of getting vaccinated and vaccinating his kids. He decided against it after his wife’s best friend died of sudden cardiac death in her sleep in April 2021, just a few days after receiving the Pfizer shot. Dan acknowledges that not everyone thinks there is a link between his friend’s death and the vaccine. “I don’t know that I’m right to make the connection and be as committed to it as I am,” he told me, “but I know that it’s not right to not engage the idea that it could be related and to take precautionary steps.”

Berkeley was once home to the Free Speech Movement, but Dan told me that it’s now the most close-minded place he’s ever experienced. “You either think with the masses or you’re a pariah,” he said. Even though unvaccinated students have a testing option in Berkeley schools, Dan and his wife have had to email their kids’ principals and the school board multiple times in the face of open hostility toward their choice. Dan told me that in one of his son’s classes, a student wrote, “Good morning to everyone except the unvaccinated students” on the whiteboard in the morning.

Dan believes that Berkeley schools are allowing bullying and ostracism of unvaccinated students to go unchecked, and that it’s a top-down issue. “You can’t imagine the list of indignities we’ve endured because we’re not getting this shot,” Dan said. “There’s no point to any of this. If you believe the vaccine works, what difference does it make what I do?” As for the school mandates, “all they’re doing is creating torment for families and individuals that don’t really deserve it.”

What’s most disturbing about the stories I heard from Dan and other parents is precisely the sense that parents and children have become the targets of bureaucrats who have been entrusted with the education of their children, but who now feel empowered to steamroller the concerns of their supposed partners and charges.

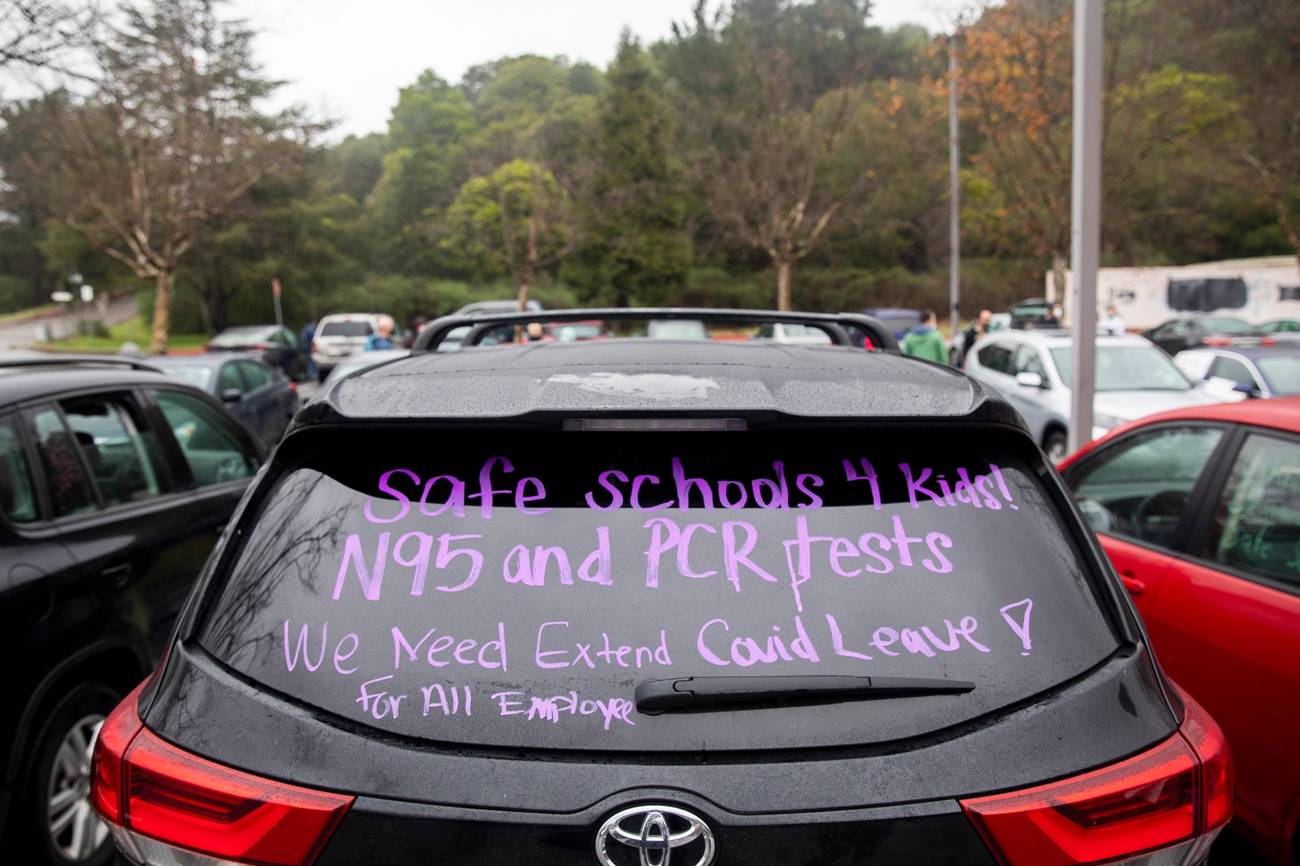

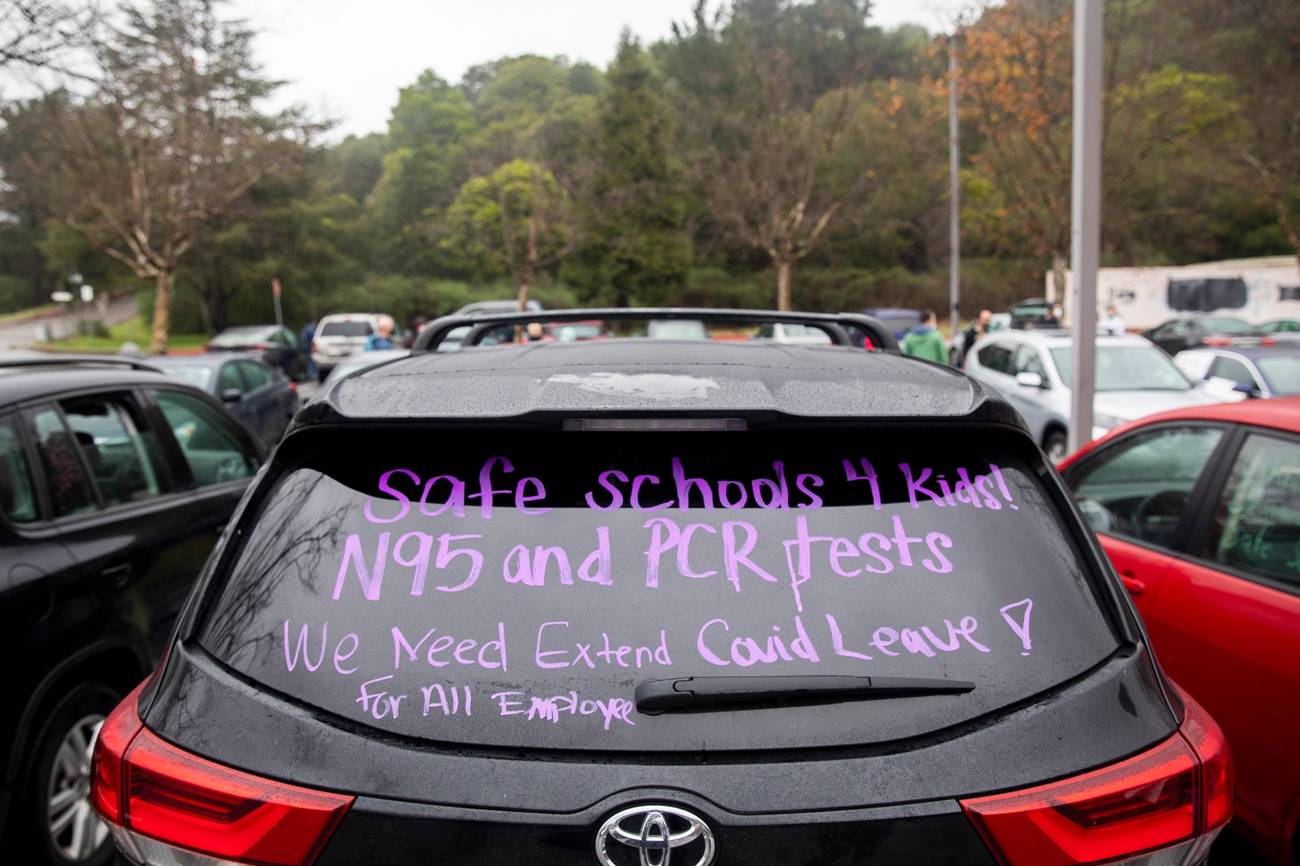

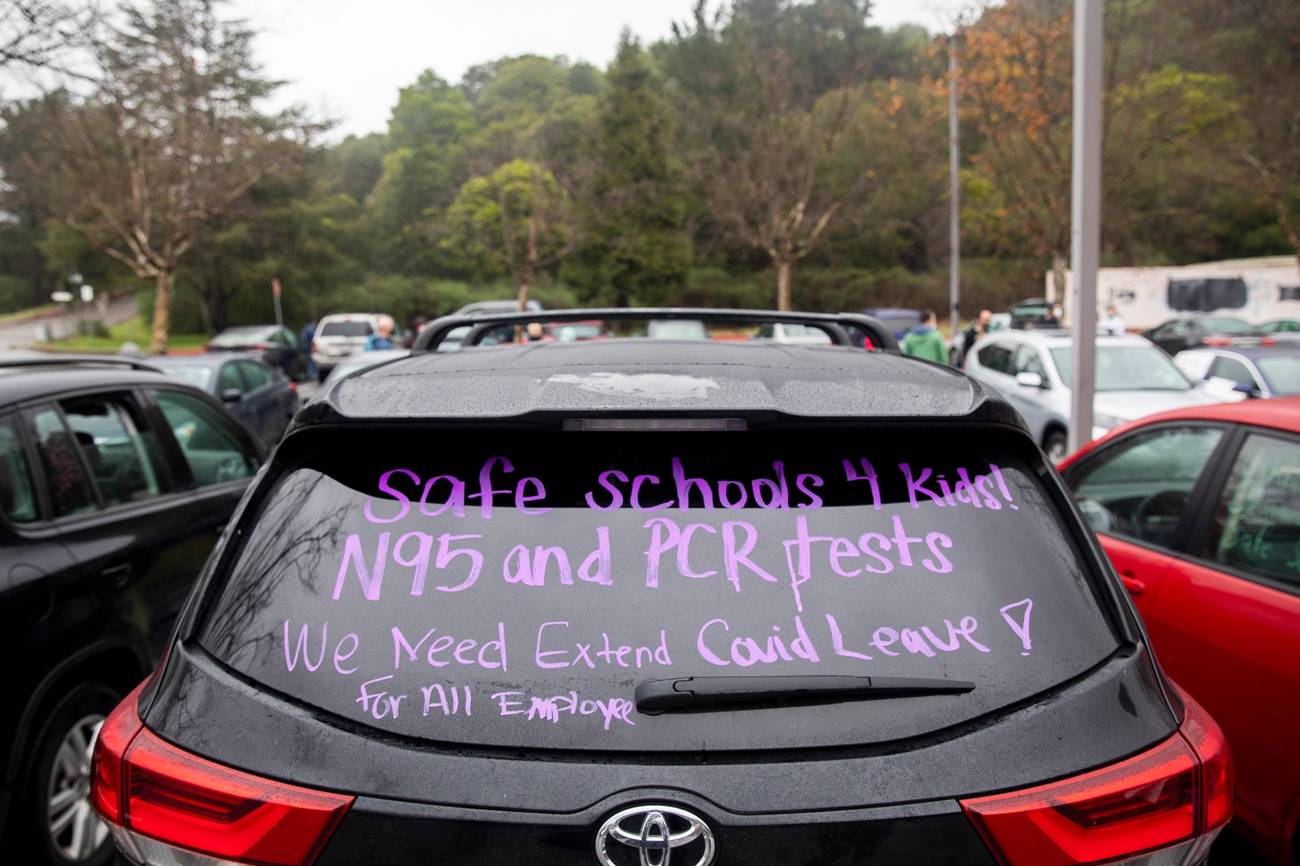

Recently, the West Contra Costa Unified School District attempted to implement a vaccine mandate despite substantial pushback from parents. Allison Palma, a parent of two students in the district, attended the school board meeting about the mandate and voiced her concerns, many of which were informed by her experience as an ER nurse. “Ninety percent of the parents that spoke at that board meeting were of the same mindset that I was,” she said. Yet the board still voted to implement the mandate. Across the state, similar battles are taking place, with school districts blatantly disregarding parent voices and destroying the sense of trust that is essential to the educational mission of all schools, no matter what neighborhood they are located in.

As a result, some parents are taking legal action. Sharon McKeeman, founder of Let Them Choose, spearheaded the successful litigation against San Diego Unified School District’s mandate. She told me that many parents involved in opposing the mandate are vaccinated and their families are vaccinated. Still, they see the mandate as a dangerous form of overreach. “I tell our families this is both a sprint and a marathon at the same time,” she said. “It’s extremely urgent for our children, and at the same time it’s going to be an ongoing legal and legislative effort.”

For California kids, the road back to normalcy has been longer than anywhere else in the country, and the disconnect between public policy and what parents want continues to widen. The question remains whether officials will eventually listen to families, or continue to cause stress and chaos in communities across the state, with the most vulnerable inevitably suffering most.

Alex Gutentag (@galexybrane) is a writer and Tablet columnist based in California.