Orbán’s Long March Through Hungary

A new dispatch from Budapest on the anti-immigrant, authoritarian takeover of civil society that’s winning voters and inspiring right-wing populists around the world

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán rose to international fame (or infamy, depending on your point of view) in the fall of 2015 when he built a barbed wire fence along Hungary’s southern border to keep out Syrian refugees. Since then, he has become the leader of the so-called Visegrád group, comprising Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, whose chief unifying stance has been their refusal to admit refugees and their defiance of the European Union; they welcome the EU’s money but openly flaunt its rules and regulations regarding human rights and democratic processes.

In an earlier article, I reported on Orbán’s success in dividing the democratic opposition and in dismantling the free press in Hungary. By all indications, his tactics have worked, both at home and abroad. His party, Fidesz, which has been in power since 2010, won the parliamentary elections last April handily, ensconcing him as prime minister for another four years. Steve Bannon has called him his “hero” and, according to a recent op-ed in The New York Times, considers him his “new best friend.” True, the European Union voted a few weeks ago (Sept. 14, 2018) to start disciplinary action against Hungary for a whole host of violations, including mistreatment of asylum-seekers; but the Trump administration, breaking with previous American policy, has “pivoted” toward Orbán (as the Times put it) by withdrawing funding that had been slated by the State Department to help nurture an independent press in rural Hungary. Since one of Orbán’s most successful projects has been to destroy the independent press outside Budapest (he’s making progress on doing the same in the capital), the State Department’s decision to divert the slated $700,000 to “other parts of Europe” was music to his ears—and a slap in the face of all those in Hungary who are trying to counter the wave of autocracy.

I returned to Budapest recently to find out what Fidesz was up to after its victory. The short answer, based on my conversations with more than a dozen Hungarians from various walks of life and on my reading of the local press, is: nothing good. Fidesz not only won the elections, it won them big: with its ally, the right-wing Christian Democrat party KDNP, it now commands a two-thirds majority in Parliament, which means that it can do, as a friend in Budapest told me, “whatever it wants.” If what it wants is unconstitutional, it can change the constitution—which in fact it did, just a few weeks after the election. Yet Orbán continues to be popular, not only in the provinces but also with some voters in Budapest. The anti-migrant rhetoric and hard-line stance against Muslims on which he built his re-election campaign have proven highly effective, as has the accompanying personal campaign against George Soros, the “billionaire speculator” as he is unfailingly identified in the pro-government press. The anti-Soros posters and billboards that were plastered all over Budapest last fall have disappeared but the post-election package of laws that included the modified Constitution was called the “Stop Soros” package.

When I arrived in Budapest toward the end of June, the latest government action that had many people up at arms was a decision, announced just days earlier, taking aim at the autonomy of the venerable Hungarian Academy of Sciences, in Hungarian, Magyar Tudományos Akademia, or MTA. The MTA, which oversees more than a dozen research institutes in the humanities and the hard sciences, and whose members include distinguished artists and scholars, will have 70 percent of its budget taken over by the newly created Ministry of Innovation and Development, headed by an Orbán appointee. Since the MTA’s budget largely determines the nature and direction of basic research by allotting funding in its institutes, the ministry’s takeover was seen as a blatant interference with academic freedom.

This was not the first time the Orbán government had muscled in on academic freedom. A few years ago, in his previous administration, Orbán appointed chancellors in the public universities who are above the rector and who determine, by their control over the budgets, which departments and academic programs will be supported and which won’t. Currently, the axe is poised to fall on gender studies. Still a very small field of study in Hungary, gender studies is taught in only one Hungarian university, ELTE in Budapest; it has been targeted on the grounds that it is purely ideological, without practical or scholarly merit—or so argued the editorial in Magyar Idők, the right-wing daily that acts as a government mouthpiece, when the decision to do away with the gender studies program was announced. In response to this threat to its autonomy, the university’s administration put up no resistance, but formal protests poured in from individual faculty members and from scholarly organizations outside the country. The latest news is that the government, responding to international pressure, has announced it was postponing the closing of the program. A victory for academic freedom, even if a temporary one.

One friend who is quite close to all this explained how the government’s interference in intellectual life can take insidious forms. A few years ago, the Orbán government created a rival institution to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, the Hungarian Academy of Arts—MMA instead of MTA. No self-respecting artist or writer has accepted, so far, to become a member of the MMA, but the temptation can be great because the MMA has a large endowment: Members receive up to 600,000 forints (about $2,200) a month for “doing nothing,” my friend said. By contrast, members of the MTA’s arts academy receive only the honor. Recently, the government came up with an even more tempting offer: Any writer or artist who has won a national prize is entitled, upon retirement, to a “pension supplement”—but to get it they must apply through the MMA, a seemingly innocuous procedural step that induces notable applicants to give a symbolic stamp of approval to this dubious institution before they can be paid. No one will condemn a person who chooses to apply, for pension supplements can make a real difference in people’s lives, but some still prefer not to have anything to do with the MMA even if it means a significant financial loss. “This is the kind of diabolical project this government comes up with,” my friend said

Maybe even more troubling than the attempted takeover of the academy has been the Orbán government’s latest step to take over the judiciary. Aware that some independent judges may not decide all cases in his favor, Orbán has created a new High Court whose judges will all be named by him. The High Court of Public Administration, part of the “Stop Soros” package passed this past spring, will decide all cases involving constitutional issues and lawsuits brought against the government. To ensure that no one challenges the legality of the new court, its existence has been written into the constitution: a newly revised constitution (the seventh since 2010) was also part of the package. Among other revisions, the document now declares that the government must protect Hungary’s “Christian culture.” One Jewish friend who is a well-known writer and academic told me: “It looks like the new constitution does not consider me or people like me as part of Hungarian culture. We’ve been there before!”

All this is due to the supermajority that Fidesz has commanded since the April elections. No one expected them to win this big, and a few extreme optimists even hoped they might not gain a majority at all. But the opposition parties didn’t manage to agree on single candidates to run against Fidesz in specific districts, which meant that their votes were splintered. Even in Budapest, where Orbán’s party is weakest, Fidesz won several seats that could have gone to opposition candidates, if only the opposition had been able to get together. As it is, the current supermajority is due to a single seat. Fidesz, a very canny party, understands the power of “divide and conquer.” Among their first steps when they came to power in 2010 was to change the electoral rules. Earlier, Hungary had a two-round system like France and some other countries with multiple parties, which allow voters to “vote their heart in the first round and their reason in the second.” Now there is only a single round, so it’s Fidesz against everyone else—and since the others are divided, Fidesz wins.

Among the people I was eager to talk with on my June visit was the philosopher Agnes Heller, who had made big news last fall with her controversial argument that Orbán had to be ousted at any cost, even if it meant cooperation among the left opposition and the right-wing party, Jobbik. Viciously anti-Semitic and anti-Roma when it first entered Parliament eight years ago, Jobbik sought to move to the center last year and became an opposition party. Heller’s idea about cooperating with Jobbik was considered too extreme by most liberals, and Jobbik itself faced dissension for its moderating move from some members. In fact, the news in June was that the party’s far-right fringe had broken off to found a separate party, the “Our Homeland” (“Mi Hazánk”) party, which would reprise the abandoned themes of “Hungary first, out with all the foreigners”—that is, Jews, Roma, Muslims. The independent weekly Hvg reported on June 28 that the fringe group’s leader, László Torockai, had proclaimed, at a rally in his hometown where men wore fascist-style “Hungarian Guard” uniforms, that “Hungary must remain a white island.” Even Orbán hasn’t gone as far as stating the racist message so bluntly, although all of his recent pronouncements point in that direction.

I met Heller in her airy apartment overlooking the Danube. At 89, she is astonishingly energetic, still invited to give speeches all the world. As a young philosopher, she was a member of the “Budapest School,” trained by the renowned Marxist thinker Georg Lukács, many of whom, including Heller, gained international reputations of their own. She lived through the Nazi occupation of Hungary in 1944, surviving in the Budapest ghetto with her mother. “That experience killed fear,” she said. “I’ve never been afraid after that.” I asked her whether she felt like saying “I told you so” after the election. “I didn’t have to,” she answered, “because people came up to me in the street to say it for me!” She’s horrified by the current situation, but not really surprised, she told me. “Don’t forget, Central Europe has had very little experience of democracy: 15 years in Czechoslovakia between the two world wars, 14 years of the Weimar Republic in Germany. In Hungary, there have been only two good periods historically: the last 20 years of the [Habsburg] monarchy before World War I, and the 1990s, because there was hope then.”

Today, hope is more fragile. When I spoke with Michael Ignatieff, the rector of the Central European University, which has been under attack by Orbán for over a year (part of the anti-Soros campaign: Soros founded the CEU in 1991), he was cautiously optimistic about the university’s future in Budapest. But the government has still not signed off on the agreement that brings CEU in line with current Hungarian legislation to allow it to stay. “We’re going on here as usual—I just made seven new hires on the faculty for next year, and the applications we received this year were just as many as before. Students are obviously not abandoning us,” Ignatieff said. He and the university’s board of trustees have decided to stay “until they kick us out.” The deadline for that decision on the government’s part is next January. The university has strongly criticized the government’s attack on gender studies at ELTE, and is maintaining its own highly successful gender studies program. But it has been forced to temporarily suspend its programs involving policy issues relating to migration, because of “recent Hungarian legislation penalizing assistance to refugees and asylum seekers, according to a recent e-mail announcement. This legislation was also part of the “Stop Soros” package. It was designed specifically to hamper the work of NGOs and other organizations that aid refugees. As a result, George Soros recently moved his Open Society Foundation, which has supported those NGOs—among other institutions like schools and hospitals—from Budapest to Berlin.

The sobering fact is, Orbán’s anti-migrant message has proven to be wildly effective, and not only in Hungary. It obviously plays a role in Steve Bannon’s admiration for Hungary’s strongman leader, as well as in Trump’s “pivot” toward him. And Orbán himself proclaims it loud and clear whenever he can. On June 16, at a conference to mark the first anniversary of the death of German Prime Minister Helmut Kohl, Orbán, after proclaiming German-Hungarian friendship for the first minute or so, proceeded to give a hard-line anti-immigration speech in English.

Here Orbán argued that the European Union, led by Germany, is on the wrong track when it tries to force member countries to accept migrants. He stated: “Can there be compromise in the migrant debate? No–and there is no need for it. […] There are countries which do not want migrants, which do not want to mix with them, and where their integration is therefore out of the question.” Hungary is such a country, he continued: Hungary would make no concessions to EU attempts to “distribute” migrants. “If we defend our borders, the debate on the distribution of migrants becomes meaningless, as they won’t be able to enter. […] the only question is what we should do with those who have already entered. Our answer to this question is that they should not be distributed, but should be taken back home.” Orbán was happy to report that just that afternoon he had had a telephone conversation with President Donald Trump, in which they discussed the “difference between a ‘beautiful wall’ and a ‘beautiful fence.’” Clearly, he implied, he and the American president have a lot in common—and he built his fence first!

On one of my last days in Budapest, I had lunch with a friend, a happily married man with a successful career as a writer. He has a cheerful mien and an easy smile, but his views on what’s happening now in Hungary, and more generally in Europe, are dark: “We are in a new epoch (korszak), which began on Sept. 11, 2001, and got greatly exacerbated in 2015 by the migrant crisis. People are afraid, they seek security, they look for “strongman” type leaders. And some politicians, like Orbán, are able to exploit their fear to their own advantage.” In his view, this epoch will last “as long as the migrant crisis and Islamic terrorism are not ended.” Judging by the recent electoral successes of right-wing parties in Italy and other European countries, his diagnosis seems to be correct. Viktor Orbán’s message is going mainstream. Writing about Poland in a recent issue of the New York Review of Books (Aug. 16, 2018), Timothy Garton Ash notes that Orbán is often cited as a model by the ruling party and its boss, Jaroslav Kaczynski. According to Garton Ash, the attitude of Western democracies plays a big role in curtailing the party’s excesses—if Poland is not yet as far gone toward autocracy as Hungary, he writes, it’s due partly to the moderating influence of world opinion. Which is one more reason why the Trump administration’s recent “friending” of Orbán is so disheartening.

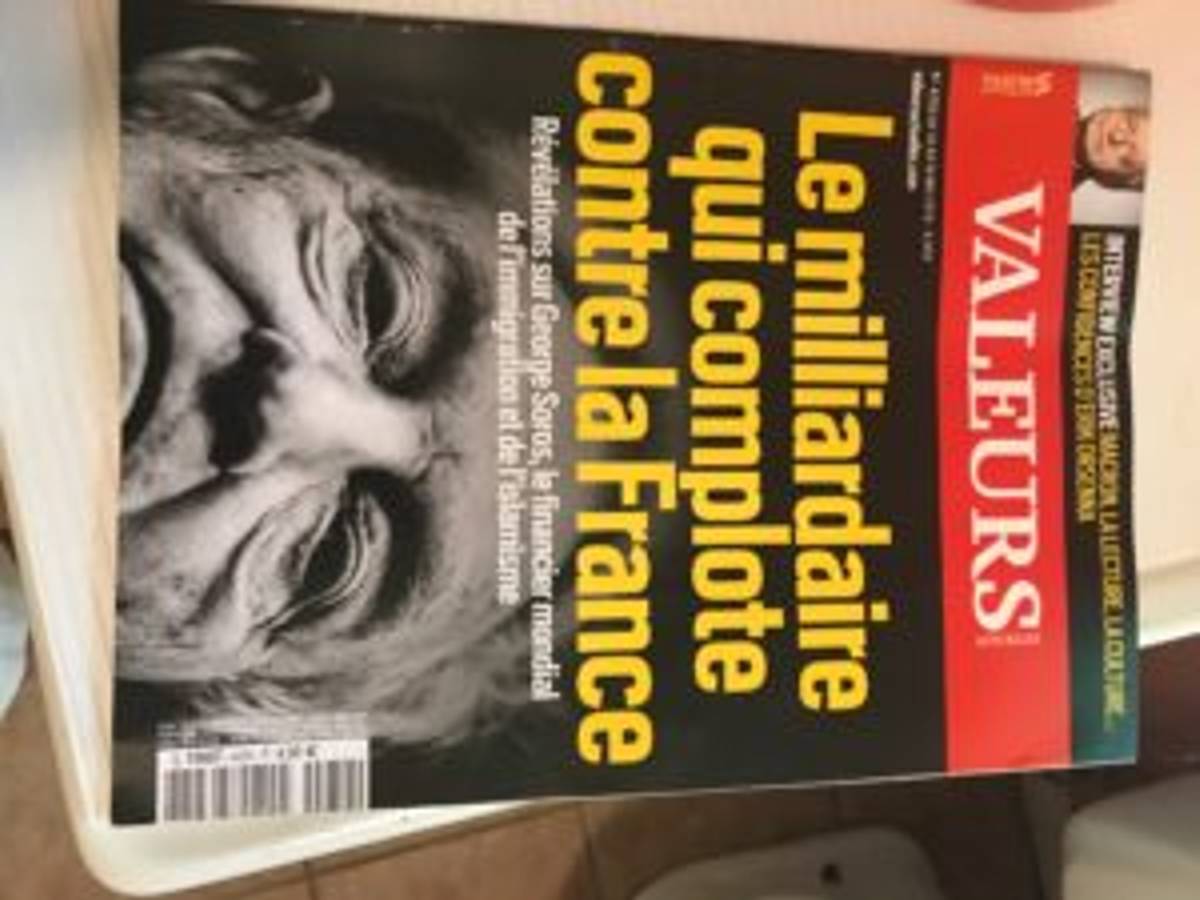

Even in France, where President Macron represents a strong voice for democracy and the EU, right-wing parties are capitalizing on anti-migrant sentiment. The extreme right-wing Front National recently renamed itself “Rassemblement National” (National Gathering), in an effort to do away with its “pugnacious fringe group” image. It and other right-wing groups in France have taken a page right out of Orbán’s playbook. In mid-May, while I was in Paris, I stopped at a newspaper kiosk and my eye was caught by a glossy magazine cover. Its title, VALEURS, looked like any number of other titles of French weeklies: L’Express, Le Point, Marianne. But Valeurs Actuelles, the magazine’s full title, is not your usual news magazine. Its former editor in chief, Yves de Kerdrel (who was replaced this past spring but still contributes editorials), was condemned by French courts twice in 2015 for inciting hatred against Muslims and Roma through its incendiary covers. The cover I saw in May (May 10-16, 2018) was nothing if not incendiary: Above a partial close-up of George Soros’ face, the huge headline blared: “The billionaire who is plotting against France.” And just below it: “Revelations on George Soros, the global financier of immigration and Islamism.” Inside, five separate articles outlined Soros’ sins, chief among them his advocacy for an “open democracy” (p. 29) and his support for NGOs that promote human rights (p. 30). Hungary’s role in bringing these sins to light was prominently featured, along with photos of a huge anti-Soros poster from the summer of 2017, taken in Budapest.

My taxi driver to the Budapest airport for my flight back to Paris was a friendly man, about 60 years old or a bit younger. We started a conversation, and after some chitchat I asked him about the recent election. “If the left parties had gotten together, they could have gotten more seats,” he said. “But they hate each other more than they hate the government party!” and he laughed. As for him, he listens to both Klub radio, the opposition station, and to the government stations, and he doesn’t really believe any of them: Politicians can talk you into anything. The Orbán government has done some pretty shady things—for example, he heard on the radio recently that when they couldn’t get the chief judge of the High Court to do their bidding, they simply dissolved the court and created a different entity, to which they named their own judges! That was back in 2010, when Fidesz also had a supermajority, like now. In his opinion, it’s not good to have that kind of majority because it allows the government to do whatever it wants.

But still, in the April elections he voted for Fidesz. “There was no one else to vote for!” The Socialists? For sure not. A more recently founded left-leaning party, the DK? No! How about Jobbik? They’re on the left, he said. The new Jobbik is to Fidesz’s left, and he wants nothing to do with them. One part has just split off, I said, but we didn’t pursue that line of thought. Instead, I asked why he thought that Jobbik was on the left. “Well, there was that poster, do you remember, where we saw Soros with his arms around a bunch of left-party leaders—and one of the ones in the photo was Vona Gábor (the head of Jobbik, who resigned after the April election). “Of course that poster was created by Fidesz,” I said. “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire,” he answered—”there must be something to it.” So he approves of the government’s campaign against Soros? I asked. Largely, yes, he answered. “He’s got his finger in everything—the civic organizations he supports want to undermine all the current governments, in Europe and in the U.S. too.” But don’t they do good things as well? I asked—”support hospitals, help people, defend human rights”? “That’s all a smokescreen,” he said. “Their real objective is to undermine the government.” So does he approve of the government’s campaign against the CEU? I asked. “Well, I know CEU’s a good thing, but if it tries to undermine Hungarianness then I’m against it. I’m a very strong believer in Hungary.”

It soon turned out that what Soros and the NGOs he supports really want is to let many thousands of “blacks” enter the country. At this point, his tone turned ugly. “Those are the people who rape women, who rob and steal—and they reproduce like rabbits! That’s one issue on which everybody in this country agrees, no matter what they say—even those who didn’t vote for Orbán agree about the migrants.” Some of them are refugees from Syria, I said. “Yes, but they’re all alike. And most of them come just for economic reasons—they want to live better than back home. And even if they’re refugees, they refuse to stay in the country where they first arrive, Greece or Italy—no, they want to head north, to England, Norway, Hungary.” He went on: “They don’t have one or two kids, or even three, but 8, 9. In 20 years, their numbers will double—Europe will no longer be white. Our culture, our history, it will all be gone—it will all be what they want. Have you ever been to Marseille, in France? Just take a look at what’s happening there! This is a problem everybody understands!”

At no time during our 30-minute conversation did I hear even a hint of anti-Semitism from this man, even when he was speaking about George Soros. Perhaps in his mind, Jews are no longer the problem: The real Others to be feared and loathed are the Muslims, whether they are black or not. In his June 16 speech, Viktor Orbán declared: “Everyone should be wary of the idea of Islam being part of any European country.” Hungary knows this from historical experience, he said, alluding to the 150-year Ottoman rule in the 16th and 17th centuries.

When we arrived at the airport, the taxi driver helpfully took my bags as far as the entrance door and said a friendly goodbye. As for me, I was left speechless.

Susan Rubin Suleiman is professor emerita at Harvard University and the author, most recently, of The Némirovsky Question: The Life, Death, and Legacy of a Jewish Writer in Twentieth-Century France.